For any public art lover or sculpture lover, the Sculpture Milwaukee exhibit will be a thrill. Along the city’s Wisconsin Avenue, the event showcases over 20 pieces. There are additional sculptures along the way to enjoy that are not part of the exhibition per se. The styles differ considerably and many are good conversation starters. It’s worth visiting in person, but if you can’t, you can see the pieces here, captured during my August visit. The exhibition runs through Oct 21st.

For any public art lover or sculpture lover, the Sculpture Milwaukee exhibit will be a thrill. Along the city’s Wisconsin Avenue, the event showcases over 20 pieces. There are additional sculptures along the way to enjoy that are not part of the exhibition per se. The styles differ considerably and many are good conversation starters. It’s worth visiting in person, but if you can’t, you can see the pieces here, captured during my August visit. The exhibition runs through Oct 21st.

{ 4 comments }

This is an extract from my recent review article in Inside Story, focusing on Ellen Broad’s Made by Humans

For the last thousand years or so, an algorithm (derived from the name of an Arab a Persian mathematician, al-Khwarizmi) has had a pretty clear meaning — namely, it is a well-defined formal procedure for deriving a verifiable solution to a mathematical problem. The standard example, Euclid’s algorithm for finding the greatest common divisor of two numbers, goes back to 300 BCE. There are algorithms for sorting lists, for maximising the value of a function, and so on.

As their long history indicates, algorithms can be applied by humans. But humans can only handle algorithmic processes up to a certain scale. The invention of computers made human limits irrelevant; indeed, the mechanical nature of the task made solving algorithms an ideal task for computers. On the other hand, the hope of many early AI researchers that computers would be able to develop and improve their own algorithms has so far proved almost entirely illusory.

Why, then, are we suddenly hearing so much about “AI algorithms”? The answer is that the meaning of the term “algorithm” has changed.

[click to continue…]

{ 30 comments }

Once in a while it’s good for the soul to acknowledge that someone you regard as stupid said something smart. Here’s Slavoj Žižek on the wisdom – that is, stupidity – of proverbs: [click to continue…]

{ 20 comments }

Kavanaugh. Suppose – just suppose – we wanted to estimate the likelihood that BK was guilty of sexual assault in his bad old “what happens at Georgetown Prep stays at Georgetown Prep” days. Given that Ford (and Ramirez) have accused him, what is the likelihood he is guilty? [click to continue…]

{ 164 comments }

The publication date for my new book, Economics in Two Lessons, is set for May 2019. Until then, I’m putting extracts up on a Facebook page I’ve set up. Here’s the first one, part of the Introduction.

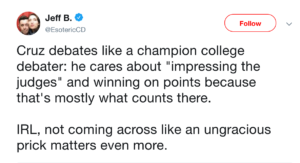

Ted Cruz has been accused of debating Beto O’Rourke in the style of a US college debater, more concerned with winning points than hearts. Twas ever thus.

In the autumn of 1992 I turned up at McGill University, Montreal. I’d wanted to go to France on Erasmus but didn’t qualify. One of my uncles, an economist at UCD, had cast around his desk for a flyer or a phone number, I don’t remember which. He named some other places, then Montreal, which we remembered was in Quebec, where two Belfast cousins had settled some time after my grandmother’s family took them in during the war. One of those cousins, Sean, still lived in Montreal, and was a pathologist at the university. His brother, the novelist Brian Moore, had written a novel about Jesuits in Algonquin that had been made into a film the year before, and featured a scene still etched in my memory of a cute, skinny young priest trying to maintain his dignity as he curled out a shit over the side of a long canoe, to the merriment of the First Nations guys rowing it. That was the clincher, so to speak.

In the first week at McGill, I auditioned for a play and tried out for the debate team. I was cast as a pillar in a Greek drama (no, I don’t know how that would have worked, either), and sent to represent McGill at a novice’s tournament in Bates College, Maine. Debating it was, then.

College debating in Ireland was just free entertainment on a Thursday or Friday night, with speakers prowling the pit of the merely medium-sized Theatre M, throwing out gags and being heckled viciously by what we then called friends, and what I now know were more like colleagues, the hacks in the box at the very top. There were often name-brand invited speakers, usually treated a little more respectfully, but only up to a point and the point was to be either masterful or entertaining, and ideally both. [click to continue…]

{ 32 comments }

I have a short piece in The Nation, [Should Immigration Laws Be Respected?](https://www.thenation.com/article/should-immigration-laws-be-respected/). Comment there or comment here. An excerpt:

> The rule of law isn’t just about people obeying the law. It is about having a fair system that works for everyone. A system where some states get to impose their will on outsiders who get neither a chance to shape the law, nor the opportunity to defend themselves against incarceration or deportation, isn’t an example of law in action but of naked force. And people don’t have a duty to submit to naked force: they have a right to resist it.

{ 102 comments }

Attention conservation notice: This is a lengthy post looking to demonstrate, should demonstration be needed, that I am not a tool of the “Koch donor network.” Also: if you are interested in l’Affaire MacLean, your time is probably better spent reading this dissection of the book by Jennifer Burns in the new issue of History of Political Economy. [click to continue…]

{ 38 comments }

As regular readers will know, I’ve spent a generation or more [1] deriding what I call the generation game – the idea of dividing the population up into birth cohorts (categories based on year of birth) such as Boomers, X-ers and so on (Millennials weren’t invented when I started) and assigning them various supposed characteristics. Most of the time, this exercise is little better than astrology. To the extent that there is any semblance to reality it simply reflects the fact that young people are, and always have been, different from old people.

But just as I have managed to get some traction with this idea, genuine cohort effects have emerged in politics in many countries. The sharpest case is Britain, where people over 65 voted massively for Brexit in the referendum and the Conservatives in the recent election, while those aged 18-24 went even more sharply the other way. As the map linked here shows, if only 18-24 year olds were voting, based on current polling data, the Conservatives would not have won a single seat[2]. If only those over 65 voted, the Conservatives would win 575 and the combined opposition 54.

This is a massive difference and can’t AFAICT be fully explained by differences in education, ethnic composition and so forth. It also represents a huge shift on the part of older cohorts, who were part of the electorate that gave Labour three terms not long ago. While there is some tendency for people to become more conservative as they age, it’s normally much more limited than this.

The explanation in simple terms, is Brexit. Most of the time, elections involving competing visions of the future. In the UK case, from the 1990s until Brexit, the contest was between hard-line Thatcher-style neoliberalism and Third Way Blairite soft neoliberalism. In the course of such debates, both sides routinely claim to be on the right side of history, to own the future and so on.

By contrast, Brexit represented an appeal to a (partly imaginary) past, against the present and the future. With the exception of a handful of neoliberal ideologues, who saw Brexit as a path to a free-market future, most Leavers were motivated by nostalgia for the glories of the past, and were willing to sacrifice the interests of the young to make a gesture in that direction.

What’s true of Brexit is true, though not to quite the same extent, of the culture war politics that have now become dominant on the political right in much of the English-speaking world. It’s driven in large measure by old men who lost the cultural battles of the 1960s and 1970s, and have never got over the fact.

The result is a situation where the right is appealing directly to members of older age cohorts with the result that younger cohorts are moving left. The most immediate effect has been to wipe out the support base of centrists of the Blair-Clinton-Keating type, who fail to appeal to either group.’m

{ 76 comments }

I’ve been a parent now for six months and change, and I have exactly nothing figured out. I have gotten pretty good at thinking of things in terms of stark tradeoffs. Hooray, he fell asleep while I was nursing him, and stayed asleep when he went into his crib! (Crap. This means a missed opportunity to put him down “drowsy but awake,” and thus to train him to fall asleep on his own.) Hooray, I am really enjoying singing this song to him right now! (Crap. This temporary alignment of my interests and his surely means I am losing all ability to discern my own interests when they diverge from his.)

Don’t judge me too harshly for this insanity. Everything written about parenting seems expressly intended to make its readers think of their choices in terms of tradeoffs. (Seriously. If you don’t want your kid to be sleeping in your bed when he’s sixteen, you must put him down drowsy but awake!)

And a lot about our social environment seems expressly intended to generate tradeoffs. Take just one example: Privileged parents generally face a choice between schooling options that middle-class parenting culture approves as best for their children, and schooling options that progressive politics regards as best ethically. A fair bit of attention has been paid to this choice in popular media over the past week, largely in response to a book by Margaret Hagerman about how progressive, middle-class parents make decisions—decisions about where to live and thus what schools their kids will attend, and with whom, etc.—that perpetuate racial inequality. This is to be welcomed. It’s an important issue. While the tradeoff is generated by policy-level decisions—our practices for funding schools, our willingness to tolerate residential segregation by race and social class, our willingness to tolerate the extreme social inequality that makes that residential segregation so consequential—the policy failure generates seriously difficult decisions for individuals.

The philosophical considerations that bear on those decisions are complex. I want to quibble with the way the ethical tradeoff is being framed in the popular media discussions of it, encouraged, perhaps, by the way Hagerman herself sometimes frames it. Consider this remark from her interview in the Atlantic:

“I really think—and this might sound kind of crazy—that white parents, and parents in general, need to understand that all children are worthy of their consideration. This idea that your own child is the most important thing—that’s something we could try to rethink. When affluent white parents are making these decisions about parenting, they could consider in some way at least how their decisions will affect not only their kid, but other kids. This might mean a parent votes for policies that would lead to the best possible outcome for as many kids as possible, but might be less advantageous for their own child. My overall point is that in this moment when being a good citizen conflicts with being a good parent, I think that most white parents choose to be good parents, when, sometimes at the very least, they should choose to be good citizens.” (Italics mine.)

Contrary to Hagerman’s worry, this does not sound even kind of crazy, and I hope her work helps to make it sound less crazy even to those who ultimately disagree with it. But we shouldn’t frame the tradeoff the way Hagerman does in this quote. It’s misleading and it’s bad marketing.

[click to continue…]

{ 109 comments }

One of the more influential studies of conservatism, Corey Robin’s The Reactionary Mind, insists that such seemingly disparate figures as Edmund Burke, Joseph de Maistre, Milton Friedman and Sarah Palin are all more or less the same, sharing the overarching goal of preserving the ruling order’s power and privilege against liberationist movements from below. In his view, the ideals conservatives tout (greater freedom, robust public morality, economic growth and deference to the Constitution) are nothing but fig-leaf cover for oppression, and anyone outside the elite who thinks otherwise is a victim of false consciousness.

Our Corey emitted a sigh over this, over on Facebook. This line of criticism of his book [amazon] was done to death years ago, no? Back when Mark Lilla was advancing the same criticisms – no better, but no worse? I will, as in days of yore, reply on Corey’s behalf. Since I think I can add a bit I haven’t said before.

The form of the objection is weird. “But, Socrates, how can you say that all triangles have three sides? That implies that all triangles are the same. But we all know that there are blue ones and red ones, big ones and little ones …”

How could you fail to see the fallacy in this pattern of reasoning?

There is nothing inherently illegitimate (‘reductionistic’) about looking and seeing whether all the things we call ‘X’ have something in common, plausibly explaining why they are grouped together.

Yet (as Corey himself says, over on Facebook) Kabaservice is smart. His book [amazon] is good. So why does he go wrong in this way – like Meno, to whom it simply does not occur to seek what all virtue cases have in common, rather than what makes them different?

Because politics ain’t triangles!

Very true. So let me put it another way. (And I’ll start calling Corey ‘Robin’. Because it sounds more official to refer to him that way!) Robin objects to what we might call the standard view. Let me quote a representative formulation by Peter Berkowitz. He’s introducing Varieties of Conservatism in America: [click to continue…]

{ 117 comments }

Endgame‘s opening lines repeat the word “finished,” and the rest of the play hammers away at the idea that beginnings and endings are intertwined, that existence is cyclical. Whether it is the story about the tailor, which juxtaposes its conceit of creation with never-ending delays, Hamm and Clov’s killing the flea from which humanity may be reborn, or the numerous references to Christ, whose death gave birth to a new religion, death-related endings in the play are one and the same with beginnings.

I cannot help but think of this passage as I read Jonah Goldberg’s erudite musings in the pages of National Review.

In the classic absurdist dramas of the 1950s and 1960s, Brittanica.com explains, European playwrights “did away with most of the logical structures of traditional theatre. There is little dramatic action as conventionally understood; however frantically the characters perform, their busyness serves to underscore the fact that nothing happens to change their existence.”

That’s a pretty good description of the sound and fury signifying nothing on display this week from Democrats and protesters alike.

In this blog post I would like to argue that, as in the classic absurdist dramas of the 1950’s and 1960’s, in Goldberg’s essay, “Theater of the Absurd Has Taken Over The Senate,” what we see is a conservative intellectual tradition that is ‘finished’, and yet at the same time intertwined with its own beginnings. The life of the conservative mind is cyclical, juxtaposing attempts to kill the stubborn flea of liberalism with lofty dreams of the rebirth – ever-promised, never fulfilled – of the conservative mind.

To put it another way, as Shmoop writes:

Waiting for Godot is hailed as a classic example of “Theater of the Absurd,” dramatic works that promote the philosophy of its name. This particular play presents a world in which daily actions are without meaning, language fails to effectively communicate, and the characters at times reflect a sense of artifice, even wondering aloud whether perhaps they are on a stage.

In conclusion I would like to argue that, just as the ‘theater of the absurd’ is about dramatic works that promote the philosophy of its name, so ‘conservatism’ is about works that promote the philosophy of its name: namely, conservatism. And, just as this particular play presents a world in which language fails to effectively communicate, so Goldberg’s essay fails, effectively, to communicate. It seems like “a walking shadow, a poor player/That struts and frets [its] hour upon the” front page of National Review, then is heard of no more.

{ 35 comments }