Unionization in the United States has been declining since the 1950s, and at a particularly rapid clip since the 1970s. Many analysts who have studied the growth of income inequality in America over the past several decades agree that union decline has played a role, and some see it as the single most important factor. The Employee Free Choice Act (EFCA), which would make it easier for employees to unionize, stands a chance of becoming law in the next year or two. Would that help to reverse the rise in inequality?

I’m not optimistic. An increase in unionization would very likely help middle and low-end households to capture a larger share of economic growth. But even if EFCA is passed by Congress, I don’t expect a dramatic surge in union membership.

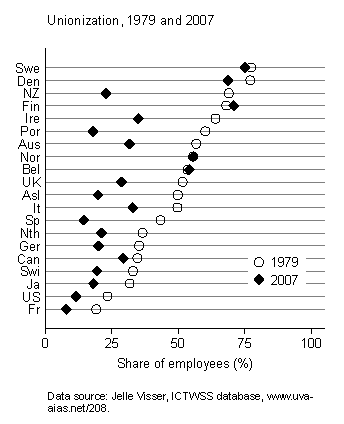

Yes, survey evidence suggests that many American workers who aren’t currently a union member would like some sort of organized representation. And yes, American labor law and its weak enforcement have been a key culprit in union decline. Yet other rich countries have labor law that’s much more favorable to unions, and unionization has been declining in most of them too. Consider the following figures, from the best available comparative data source. Only a few countries have avoided a sharp fall in unionization, and they’re mainly ones in which eligibility for unemployment insurance is tied to union membership.

Why the widespread decline in unionization? The causes are multiple: greater competition and profit pressure on employers, the shift from manufacturing to services, increases in part-time and temporary employment, shrinking public sectors, and attitudinal shifts across generations, among others.

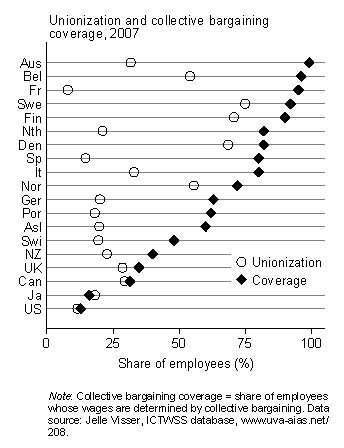

How then are unions in other countries able to secure greater wage gains, and thus less inequality, than their American counterparts? The key is “extension” practices: by agreement between union and employer confederations (most nations) or due to government mandate (France), union-management wage settlements apply to many firms and workers that aren’t unionized. The following chart shows that in a number of countries the share of the workforce whose wages are determined by collective bargaining is much larger than the share of workers who are union members.

I would like to see EFCA become law. The ability of workers to bargain with management collectively rather than individually is, in my view, an important element of a just society, and these days the playing field is too heavily tilted in management’s favor. But I doubt EFCA will get us very far in reducing income inequality. Extension of union-management wage settlements would likely have a bigger impact, but at the moment that isn’t even part of the discussion.

{ 24 comments }

mpowell 04.14.09 at 12:59 pm

Good lord, I cannot even imagine the response if this was proposed in the american political sphere. We are shifting the overton window, but we are not there yet.

Barry 04.14.09 at 2:50 pm

I can *not* believe that a whole horde of right-wingers haven’t dumpe a truckload of anti-union cliches on us by now. Are they asleep?

anonymous 04.14.09 at 3:09 pm

Unions aren’t the answer, for the simple reason that unions are not appropriate for every type of worker. And if you only have unions for some workers, that will obviously lead to inequity. So it’s much better to just forget about unions as a way to raise wages and just have a social safety net for everyone.

James C 04.14.09 at 3:25 pm

But then unions are usually instrumental in the political struggle for a social safety net. Perhaps then EFCA could, by boosting unionization even in a non-dramatic kind of way, help bring extension of collective agreements to the non-unionised onto the political agenda?

Henri Vieuxtemps 04.14.09 at 3:37 pm

Unions are a part of “the answer”. With EFCA enacted, employers would have to moderate their appetites accordingly; the ability to organize a union would produce a new (and better) equilibrium. Obviously, inside the existing socio-economic system there is no such thing as “the answer”.

Trevor 04.14.09 at 3:38 pm

If unions are not the answer, what is the answer to reducing income inequality? Historically, do we not explain the occurrence of the middle class as partly in consequence of unions? Can a short list even be made of possible options that really and truly effectively level the mountains and valleys of an income graph?

In my mind, the ‘positive liberty’ unions represent a worthwhile social and political project. If not unions, then certainly willful, constructive, activist groups working democratically toward real goals with results.

We can expect innumerable ‘negative liberty’ proposals such as tax-cutting, laissez-faire blackboxing of processes into ‘markets’ and so on, but I also believe historically we are at something of a juncture that these proposals occur as either canards or shibboleths into a certain way of thinking, and frankly, ORDERING the world.

In a rhetorical sense, the very fact that we ask the question, “Are unions the answer?” seems to me to supply the answer: emphatically YES.

Shifting overton windows, rejuvenation of the salience of solidarity? I’m all for it.

StevenAttewell 04.14.09 at 4:23 pm

I think this is kind of over-generalizing – while it’s true that there have been strong factors causing union decline, it’s important to disaggregate over time, so that we can catch specific eras in union density.

Union density has declined, but the pace of decline has not been the same since the 1970s – at least in the U.S. There was a gradual decline from 1960s-1970s, a much steeper decline in the 1980s, and it’s leveled off since. While I’m not sure about the case in Europe, I wouldn’t be surprised that the same process occurred.

As a matter of fact, U.S union density has actually increased in recent years – it increased from 12% to 12.1% in 2007, and from 12.1% to 12.4% in 2008, the first increases in 25 years. It’s not a very fast rate of increase, and obviously two years isn’t a lot of data to go on, but it does at least suggest a few things.

First, that certain factors have run their course. The shift from manufacturing to services has already happened, to the point where declining numbers of industrial union jobs is no longer outpacing organizing. Similarly, attitudinal shifts have changed – previous generations, especially those who were in their 20s during the Reagan Years, and Gen. X, were more conservative towards unions than workers are today. Your own data points to this.

Second, if union growth is happening, you don’t need “a dramatic surge” to change things on the ground over time. If the current rate of about .25% per year stays where it is, then you’re going to see union density increase to 14.5% in ten years, 17% in 20, and you’re back to 80s levels in 30, If EFCA passes, and union density growth rates only increase to .5% per year, you’re looking at 17% in ten years, 22% in 20, and 27% in 30, and you’re up close to where we were back in the 70s. Keep in mind that union density growth rates have never been very fast – outside of a few peak years, such as the big organizing drives of ’35-37, unions grew generally at a pace of about 1% per year from the end of the war to the 1970s.

salacious 04.14.09 at 4:30 pm

“The ability of workers to bargain with management collectively rather than individually is, in my view, an important element of a just society”

I’m curious about this. I agree that unionization has excellent consequences, but this sentence seems to maintain that unionization itself is morally significant. If we could achieve greater equality, fairness, etc. through different policy methods, would you still argue for strengthening unions?

Sebastian 04.14.09 at 4:32 pm

“As a matter of fact, U.S union density has actually increased in recent years – it increased from 12% to 12.1% in 2007, and from 12.1% to 12.4% in 2008, the first increases in 25 years. It’s not a very fast rate of increase, and obviously two years isn’t a lot of data to go on, but it does at least suggest a few things.”

I’m not sure I understand what you mean by union density. Do you mean percentage of some group that is in a union? If so, I can think of a plausible alternative explanation: it is harder to fire/layoff union empoloyees until your whole company goes down in flames. That fact is probably a mixed bag for the economy in general. But I would think that the likely shutdown in fact (if not in name) of at least one of the US automakers is going to change that statistic when it happens.

As for the general discussion, I wonder if the issue is that most US unions are currently structured in a way that still fits with the “one employer most of your life” concept which is out of touch with reality. Unions which don’t follow that model seem to be doing better (in terms of membership).

David Wright 04.14.09 at 5:36 pm

The use of collective bargining coverage instead of union membership is an interesting innovation. You assert that this is well anti-correlated with Gini coefficient, but you don’t make the case for that assertion in your post. The OECD data on Gini coefficients are available here. Casual perusal indicates there will be good anti-correlation, but I haven’t computed it or generated a scattergram. Doing so would help your case. (It would also be good to do an analysis segregated by population, since it is often argued that smaller countries have less inequality for sociocultural rather than policy reasons.)

Tom West 04.14.09 at 7:29 pm

I wonder if the issue is that most US unions are currently structured in a way that still fits with the “one employer most of your life†concept which is out of touch with reality.

Isn’t that one of the advantages? If employers can’t get rid of unionized workers very easily, workers are more likely to be able to hold the same job for life, with the consequent advantages for their financial security and overall happiness (and of course overall cost of decreased efficiency and overall societal wealth, but nothing comes for free…)

Tom West 04.14.09 at 7:35 pm

Unions aren’t the answer, for the simple reason that unions are not appropriate for every type of worker. And if you only have unions for some workers, that will obviously lead to inequity.

Not necessarily. Unionization is most useful when the market clearing wage rate is much lower than the value the employee contributes to the company. For many jobs, the market clearing wage rate is already appropriate, and unions would add little. Those employment markets, already competing for scarce workers, would not suffer (except perhaps relatively, but they generally pay fairly well already).

Dan in Euroland 04.14.09 at 7:36 pm

Richard Epstein believes that the mandatory arbitration provision of the EFCA could be ruled unconstitutional at 9-0. Obviously he as a different political position than you, but I do find it interesting that he thinks that the Stevens-Souter-Ginsburg-Breyer wing of the court would not go for this provision. (Note his actual paper on the topic is here.)

james 04.14.09 at 7:59 pm

Even if Unions represent the best possible solution for wage inequality, card check still seems like an bad idea. Secret ballots are a successful and time test method for allowing people to vote their preference without threat of reprisal.

harry b 04.14.09 at 8:34 pm

And for employers to shape those preferences by making credible (though often insincere) threats of exit.

StevenAttewell 04.14.09 at 9:13 pm

Sebastian:

Union density refers to the proportion of the entire workforce that’s represented by unions. Now, the possibility that there are more non-union than union people being layed off is a real one, but the same statistics that give us the density rate also keep track of the whole numbers of union workers – and those went up by about 400,000.

gordon 04.15.09 at 12:19 am

I tried to download Prof. Kenworthy’s link at (http://cows.org/joel/pdf/a_043.pdf) but got a message that the download was damaged and couldn’t be opened by Adobe. Is there another link which might produce a readable download? Maybe if we had the name of the paper we could find it at COWS.

Salacious, I suspect Prof. Kenworthy’s “just society” refers to Galbraith’s “countervailing power” or similar concept, not a moral imperative.

I’m a little surprised that Prof. Kenworthy didn’t refer to the work of David Card (.pdf) and others who have published with him.

Finally, I wonder whether Prof. Kenworthy realises that Australia is closer in time to an era of greater union influence than is the US. It was only in the later phases of the Keating Govt. (from 1991) and then the Howard Govts. (from 1996) that a systematic attack on union influence (as opposed to ad hoc fulminations) became a major policy plank of Australian Govts. If Prof. Kenworthy is a little uncertain of the Australian background, he could try this paper as an introduction.

StevenAttewell 04.15.09 at 12:44 am

James: the reason that EFCA has been introduced is specifically that “Secret ballots are” NOT “a successful and time test method for allowing people to vote their preference without threat of reprisal.” As this (http://www.cepr.net/documents/publications/dropping-the-ax-2009-03.pdf) CEPR report shows, in 26% of election campaigns, workers are illegally fired for their union activity. In 92% of union elections, employers hold mandatory group “captive audience” vote-no meetings, and in 78% of union elections, employers order supervisors to hold one-on-one meetings with their employees ( Kate Bronfenbrenner, Uneasy Terrain: The Impact of Capital Mobility on Workers, Wages and Union Organizing, U.S. Trade Deficit Review Commission, 2000). This is not a successful process.

Sebastian 04.15.09 at 3:10 pm

Interestingly, the problem doesn’t seem to be the secret ballot…

lane 04.15.09 at 3:15 pm

David Wright (#10): The chart you’re looking for is on p. 121 of my book Jobs with Equality. There’s a fairly strong negative correlation: high bargaining coverage is associated with low earnings inequality.

james 04.15.09 at 5:20 pm

So the problem is not secret balots but that employers are able to legaly or illegaly convince the employees to vote no. So the EFCA is designed to give Union reps the same kind of fear power that is considered evil when used by the employers. Not finding this a convincing arguement.

A recommendation suggested by a Union advocate was to keep the secret ballots but greatly shorten the time between the call for union vote and the vote itself. This limits the length of time the employer has act.

StevenAttewell 04.15.09 at 5:49 pm

James:

By definition, a union rep does not have “the same kind of fear power that is considered evil when used by the employers.” Union reps can’t order you to attend a meeting or watch a movie or read a pamphlet, can’t threaten to cancel the health care plan and the pension if the union comes in, can’t threaten to shut down the plant or replace everyone with illegal immigrants or threaten to call la migra on you, can’t reassign you to the midnight shift or raise your daily quotas by 50%, can’t accuse you of stealing company property, can’t fire you for laziness/insubordination/other-excuse-of-the-week, and they can’t order supervisors to spy on you or be fired (supervisors aren’t covered under labor law, see?).

The only kinds of fear power a union rep could have are already illegal, and in any case, it’s highly counter-productive to try to sign people up using fear – sure you might get a card, but you’re not going to get a member who’ll attend meetings, who’ll maintain the provisions of the contract, who’ll walk the picket line, who’ll man phonebanks and walk precincts, etc.

Shortening the time for elections won’t solve things, because employers can just up the pressure of their tactics, spend more money in a shorter time, and because a lot of the power imbalance is quite legal – captive audience meetings, required one-on-one meetings, forcing supervisors to spy, threatening closure/cancellation of benefits, and so forth.

gordon 04.16.09 at 11:50 pm

Further and belatedly to David Wright’s comment (#10) about bargaining coverage: the C&A Commission used regularly to magnify bargaining power by “roping in” workers covered by awards other than the award varied. These decisions were regularly attacked by employers on the grounds that they were inflationary etc.

Andrew 04.17.09 at 5:09 pm

@David Wright 04.14.09 at 5:36 pm

You assert that this is well anti-correlated with Gini coefficient, but you don’t make the case for that assertion in your post. The OECD data on Gini coefficients are available here. Casual perusal indicates there will be good anti-correlation, but I haven’t computed it or generated a scattergram.

Oddly enough, I did that a few weeks ago here. r = -.659

Comments on this entry are closed.