This is a guest-bleg, inspired by Quiggin’s Zombie Economics project.

I teach in NYU’s Journalism department, where we have strong concentrations in both business and science reporting. I’m looking for some way to label and describe a particular flavor of bad economics reporting, so as to make the students more alert to it, as consumers and possible producers of such reporting.

Here’s the backstory. A couple of weeks ago, my friend Tamar Gendler introduced me to the the problem of easy knowledge, the notion that if you believe a particular assertion, you can produce inductive chains that lead to overstated conclusions. “I own this bike” can be seen as an assertion that the person you bought it from was its previous owner.

But of course you don’t know if that guy in the alley had the right to sell it, so an assertion that you own the bike can generate easy knowledge about whether he did. Instead, “I own this bike” should be seen as shorthand for “If the guy in the alley was the previous rightful owner, then I am its current rightful owner.” (Oddly, this also describes the question of the Elder Wand in Harry Potter Vol. 7, pp 741 ff. Tom Riddle died of easy knowledge.)

I was reminded of easy knowledge while reading Thomas Edsall’s NY Times column on

Can’t We All Be More Like Nordics? Asymmetric Growth and Institutions in an Interdependent World, a paper by the economists Daron Acemoglu, James Robinson and Thierry Verdier. (Acemoglu goes on to discuss this work in a post titled Choosing your own capitalism in a globalised world?.)

In their paper, Acemoglu, Robinson and Verdier model a technologically interdependent world where countries can chose either cutthroat or cuddly capitalism (the US and Sweden being the usual avatars) and each country can be a technological leader or follower but those choices are not orthogonal.

They then examine this model, and discover that:

…interpreting the empirical patterns in light of our theoretical framework, one may claim (with all the usual caveats of course) that the more harmonious and egalitarian Scandinavian societies are made possible because they are able to benefit from and free-ride on the knowledge externalities created by the cutthroat American equilibrium.

Not just the US but indeed the whole world would be worse off if we had public health care, because we have to treat poor people badly if Larry Page is to get rich, so that the Swedes can copy us. Because innovation.

Now there’s nothing too surprising in this sentiment — the headline “Neo-Liberalism Woven into Fabric of Universe, say Economists” could have run unaltered in every year since 1977. What is surprising — or at least what Tamar made me see with new eyes — is that the entire exercise is a machine for smuggling easy knowledge into public discourse.

Imagine I decide to model multiplying a number by itself, but, to simplify the calculations, I make the simplifying assumption that integers in the range [0,1] can stand in for all numbers. After running exhaustive tests, I confirm that X*X = X. I can now publish a paper that says “Interpreting the empirical patterns in light of my theoretical framework, one may claim (with all the usual caveats of course) that multiplying a number by itself creates no change in its value.”

And that’s true, right? As long as you accept my theoretical framework (with all the usual caveats), you also have to accept that X2 = X. After publication, the press can then report that teaching children “squaring”, as liberal school districts so often do, is a waste of tax dollars.

The only difference between my research into self-multiplication and Can’t We All Be More Like Nordics? is that it’s obvious what I’m up to, but the form is identical: Start with some assumptions, then test them, where the result is never anything other than foregone. Then claim that because the expected conclusion turned out as expected, belief in the assumptions is strengthened. (This is a generalized case of Daniel Davies’ rule for debating Milton Friedman.)

In Can’t We All Be More Like Nordics, as in all great intellectual smuggling, the miracle occurs in Step 2:

Second, we consider that effort in innovative activities requires incentives which come as a result of differential rewards to this effort. As a consequence, a greater gap in income between successful and unsuccessful entrepreneurs increases entrepreneurial effort and thus a country’s contribution to the world technology frontier.

If we assume that innovation requires income inequality, then we can conclude that innovation requires income inequality. QED.

This presented as fairly self-evident — “the well-known incentive-insurance trade-off … implies greater inequality and greater poverty (and a weaker safety net) for a society encouraging innovation” — even though a moment’s reflection is enough to bring up a host of questions:

bracket?

One could go on and on.

The danger of papers like Can’t We All Be More Like Nordics? is not that there are sloppy assumptions; academic work is supposed to be self-correcting over the long haul. It’s dangerous because the press presents these papers as if they are scientific experiments, where prior assumptions were vetted and where the outcome was in doubt.

But neither of those things is true. The only thing Acemoglu, Robinson and Verdier show is that math continues to work as expected. They neither checked nor tested their initial assumptions in the design or outcome of the model.

This misdirection worked perfectly. When discussing the paper, Thomas Edsall (who I generally like) describes Can’t We All Be More Like Nordics? and its detractors, but then, when he gets to the part where he would grade the competing assertions, he throws his hands up:

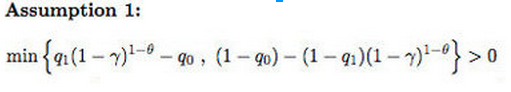

For self-evident reasons, it is difficult for a political columnist to adjudicate these warring claims. Why? Here is Acemoglu, Robinson and Verdier’s first assumption:

That sure is a lot of math symbol things right there! This so frightens the ordinarily incisive Edsall that he forgets that if the assumptions are wrong, all the math in the world won’t produce a useful conclusion.

Now a lot of this is commonplace — economics has loopy and unsupportable views of human nature, economic modeling often assumes spherical cows, and so on — but what I need is something a bit more scalpel-like, a word or phrase or short description that captures the danger of thinking that self-consistent economic conclusions should lead us to believe in the real-world applicability of the assumptions.

I want something that reminds students “Don’t just look at the conclusions, which can be as mechanistic as a wind-up toy. Look at the assumptions.” Any ideas? (I don’t think ‘easy knowledge’ is it, as it isn’t self-explanatory, though instant comprehension may be an unreachable goal.) Is there any label for this habit of camouflaging suspect assumptions while emphasizing obvious conclusions?

{ 136 comments }

Joshua Gans 06.13.13 at 5:34 pm

Perhaps consider an analysis like this one for politics. http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2277443

LizardBreath 06.13.13 at 5:36 pm

Not to be obvious, but isn’t that precisely “begging the question”?

Stewart Denslow 06.13.13 at 5:37 pm

It comes awfully close to “garbage in – garbage out”.

Jim Buck 06.13.13 at 6:05 pm

Cheese-making.

You have cheese? You must have started with milk.

Jim Harrison 06.13.13 at 6:05 pm

Alas poor LizardBreath, it’s hard to complain about “begging the question,” now that “begging the question” no longer means begging the question.

Lee A. Arnold 06.13.13 at 6:11 pm

affirming the consequent?

Martin Bento 06.13.13 at 6:14 pm

“Assuming a can-opener”, though the meaning is not obvious on its face, refers to a fairly well-known joke, one that is appropriately on economists. It lends itself to formulations like “let’s see if we can find the magic can-opener here”. Then the assumptions themselves can just be called “can openers” or “magic can openers”

LizardBreath 06.13.13 at 6:46 pm

Ooh, ‘assuming a can-opener’ is definitely better than just ‘begging the question’. Says the same thing, but it’s economics specific.

Jon Strand 06.13.13 at 6:48 pm

Proving the obvious by way of the dubious

bob mcmanus 06.13.13 at 6:51 pm

How about calling it “Evil?” We have a class-war going on around here, and this is not a benign and silly error, but a piece of propaganda that will damage millions of vulnerable people.

As far as I know, unlike a Nazi or Klan member or Polanski, Ken Rogoff can still appear in public, at conferences, and even get published in the Times.

What would a self-disciplining economics profession look like? A battlefield.

Cervantes 06.13.13 at 6:53 pm

Indeed. This seems to be an extremely elaborate way of asking the world’s most basic question about logic. As others have said, it’s simply good old circular reasoning.

The “assume a can opener” joke is a little different however. Economics 101 begins with a whole lot of assumptions which do not pertain in the real world, i.e. are not true. Then an elaborate theory is spun therefrom, not necessarily involving circular reasoning; but the conclusions of the theory are then assumed to apply to the real world, which they don’t.

The joke goes like this. An economist, a chemist and a physicist are marooned on a desert island. A case of canned beans has floated ashore. We don’t have to starve after all! But oh shit, we don’t have a can opener. “Assume a can opener,” says the economist. It isn’t assuming the consequent, but it isn’t true either. They starve.

fledermaus 06.13.13 at 6:55 pm

“Is there any label for this habit of camouflaging suspect assumptions while emphasizing obvious conclusions?”

I believe it is called “economics”

Kevin Donoghue 06.13.13 at 7:02 pm

The problem isn’t with economics reporting, it’s with economics.

In The Spatial Economy the authors mention a physicist who said to them, “So you’re telling us that agglomerations form because of agglomeration economies.â€

Basically what we need is more people rude enough to say things like that.

James Conran 06.13.13 at 7:05 pm

There seems to be a ” at the end of all the links rendering them non-functional.

Dallas 06.13.13 at 7:05 pm

Am I the only one having trouble with all of the links? They all end with an extraneous quotation mark, and the first link for the paper is neither the paper, nor the NYT discussion of said paper. The article is http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/05/29/why-cant-america-be-sweden/ and the paper is http://economics.mit.edu/files/8172

Henry 06.13.13 at 7:10 pm

Links should be fixed.

bob mcmanus 06.13.13 at 7:12 pm

“Assume a can opener,†says the economist. It isn’t assuming the consequent, but it isn’t true either. They starve.

Nah. Assume that a tibia sharpened against a femur is sharp and hard enough to open a can.

sigh 06.13.13 at 7:13 pm

Acemoglu and Robinson’s earlier response is pertinent: http://whynationsfail.com/blog/2012/10/4/economic-research-vs-the-blogosphere.html

afinetheorem 06.13.13 at 7:15 pm

This post is just so incredibly misleading, and if anything, it proves to me the problem with a lot of science journalism.

Daron Acemoglu is neither an idiot (he is surely a future Nobel winner) or a hack – indeed, in many ways, he is quite left-wing. If you read a paper of his and think the argument is “Not just the US but indeed the whole world would be worse off if we had public health care, because we have to treat poor people badly if Larry Page is to get rich, so that the Swedes can copy us. Because innovation,” then the problem lies with the reader, and not the paper.

The paper is simple. We observe similar countries adopt asymmetric policies. One type of policy appears to generate higher welfare. Why, then, does the other country not adopt it? Well, under certain conditions (and this is quite non-obvious!), the equilibrium can be asymmetric: Sweden can be better off than the US, but should the US match Sweden’s policies, the US would be even worse off. These conditions are not general; the bulk of the paper is devoted to exploring the conditions under which we could see such asymmetry. All the supposedly impossible to interpret Assumption 1 says is that for a wide variety of risk preferences, entrepreneurs must receive a higher payoff if their project succeeds than if it fails.

The political angle in the post above also seems very strange: Acemoglu et al are totally clear in the conclusion that these types of equilibria are interesting precisely because a “Sweden” in their model makes the people better off! They are absolutely not making any normative claim about free-riding or the like.

Finally, in the last paragraph: considering the assumptions rather just the conclusions is equally problematic (and ironic, given that this post takes shots at Friedman – considering the assumptions was his methodological stance, and he was wrong here). Reading economic theory means considering the steps of the proof, or the way the abstract assumptions combine together to generate the stated conclusion. Because journalists covering both economics and the hard sciences tend to have relatively poor quantitative backgrounds, they often skip this step, to the harm of their readers.

Kiwanda 06.13.13 at 7:16 pm

The “X^2 = X” example is covered by “garbage in, garbage out”, and maybe the ARV example as well, although their particular problem seems more like circular reasoning, a.k.a. assuming the conclusion. Edsall’s problem with the math adds some “proof by intimidation”.

Kevin Donoghue 06.13.13 at 7:26 pm

Edsall’s problem with the math adds some “proof by intimidationâ€.

I’m inclined to refer to the use of maths to bamboozle the laity as the Euler Gambit, although the story that Euler pulled that trick on Diderot seems to be a myth:

https://cs.uwaterloo.ca/~shallit/euler.html

James Conran 06.13.13 at 7:32 pm

I think Sowell’s main sin is taking the ARV too seriously, perhaps more seriously than the authors do themselves. In terms of communicating what the paper is to a lay audience, I think he way underemphasizes a key feature of the paper – that it has no empirical component except the “stylized facts”: that the the US model of capitalism is 1) more “cutthroat”, i.e. competitive and non-egalitarian, than others and 2) more innovative.

Both facts can be contested (regarding the first claim, the Rehn-Meidner model we’re told about always sounded very cutthroat to me – nationally centralized collective bargaining as a means of driving out of business low-productivity firms who couldn’t afford the resulting wage settlement). More importantly though (in terms of Sowell’s article), AVR make no serious attempt to establish either. Nor is their model tested against anything more than these assumed facts. You have focused on the theoretical assumptions (inequality provides incentives for innovation) but there are also almost no non-assumed empirical reference points in the paper. I’m not sure that comes across as clearly as it should in Sowell’s summary.

Sowell quotes Acemoglu acknowledging this (“In our model (which is just that, a model)…”) but then he (Sowell) slips into the language of “findings”. Purely theoretical papers do have findings, but in a special sense that a journalist might want to explain. Rodrik’s quoted reference to the paper as a “thought experiment” gets at the same point, but I’m not confident the casual lay reader would come away realizing the nature of what the paper does, nor that more typically social scientists test their theories empirically (not that untested models can’t be of value). Sowell describes it as technical, which it certainly is, but so too would be ,e.g., a statistical analysis – but that would be a very different paper.

James Conran 06.13.13 at 7:38 pm

Whoops I kept on writing Sowell rather than Edsall.

Clay Shirky 06.13.13 at 7:41 pm

Working back to front, @kiwanda, I love “proof by intimidation”, and I think that will go a long way in the conversation with students, thanks.

@finetheorem, what I disagree with is precisely this: “Reading economic theory means considering the steps of the proof, or the way the abstract assumptions combine together to generate the stated conclusion.”

That is exactly what’s wrong with this paper, and with much journalism about economics. If the steps of the proof are mathematical, then the proof shows only that if the dominoes are placed right, then one push knocks them all down.

And the authors are, in fact, making a normative claim, because they assume not just that entrepreneurs look for higher returns to risk, but that, among other things, entrepreneurship and inventiveness are elided as qualities, that the value of success can’t be expressed in non-monentary rewards and still satisfy the inventors, and so on.

The non-obviousness of assymetric equilibria does nothing at all to say why they start with the idea that “a greater gap in income between successful and unsuccessful entrepreneurs increases entrepreneurial effort”, given the not inconsiderable number of counter-examples.

@Cervantes and @LizardBreath, I should have been clear that I wasn’t looking for a description of the fallacy itself — circular reasoning is right (though begging the question has become so debauched as to be useless in this situation.) What I’m looking for is something to alert future journalists that they shouldn’t fall for this trap — recognition of something having to do with professional practice, not logical fallacy, in other words. (Though the two are often linked.)

@MartinBento, I was not familiar with ‘Assume a can opener…”, but that’s just about perfect, as it says something about economists, not just economic logic. It works better than the Spherical Horse/Spherical Cow joke to boot. Winrar.

Clay Shirky 06.13.13 at 7:49 pm

Oh, and crossing in the ether, @James_Conran posts for me — “Purely theoretical papers do have findings, but in a special sense that a journalist might want to explain” is just right.

Also, about this — “the Rehn-Meidner model we’re told about always sounded very cutthroat to me – nationally centralized collective bargaining as a means of driving out of business low-productivity firms who couldn’t afford the resulting wage settlement” — my wife is doing some research on varieties of European welfare (related to her work on basic income) and has been absolutely overflowing with stories of how much of a one-off Sweden has been in terms of the bargain struck between the central union, large businesses, and the government.

By this point, what people mean when they talk about “the Swedish model” is as much about an imaginary country that’s a lot like a cold version of France as it is about actual existing Sweden.

Herman 06.13.13 at 7:57 pm

Acemoglu:

“…interpreting the empirical patterns in light of our theoretical framework, …”

This appears to be the usual euphemism these days. Note that Acemoglu does not make a convincing case as to what makes his theoretical framework convincing. For him that point is not important.

This is not assuming the can opener, it is assuming the can itself. Begging the question seems correct.

@afinetheorem:

“Daron Acemoglu is neither an idiot (he is surely a future Nobel winner) or a hack”

A no. of people who know him do think Acemoglu is in fact an idiot, unfit to be doing social studies. Though in academic economics, where near autistic minds are highly regarded, that may be seen as a compliment rather than a criticism, for the same can be said of Tom Sargent or David K Levine.

P O'Neill 06.13.13 at 7:57 pm

#18 They are absolutely not making any normative claim about free-riding or the like.

Page 35 of the paper

An interesting implication of this result is that country j, which has a stronger labor movement or social democratic party, benefits in welfare terms by having both equality and rapid growth, but in some sense exports its potential labor conflict to country j’ which now has to choose a reward structure with significantly greater inequality

Dogen 06.13.13 at 8:06 pm

I’m late to this game, but it looks to me like you’re describing a tautalogy mascarading as a proof.

afinetheorem 06.13.13 at 8:10 pm

@P O’Neill: that statement is not at all normative.

@Clay: I disagree considering the importance of the steps of the proof. Proofs in theoretical social science and proofs in mathematical logic are not metaphysically identical. Social scientific proofs are in the context of a model, where the axioms are replaced by assumptions. Assumptions are not truth-valued. Acemoglu et al’s paper should be read to say “Let’s take it as given that there is some link between entrepreneurial activity and the rewards to risk-taking behavior. Let’s then let there be a number of ex-ante identical countries who can choose social insurance policies. Do they necessarily choose the same ones in equilibrium?”

If the answer is “sometimes no” then we can investigate what conditions might matter and what might not. Since the assumptions (not just about the entrepreneurship-risk link, but also the ex-ante identical countries assumption!) are abstractions, if you are to accept the conclusion, you must understand how those assumptions interact to generate the conclusion. In this case, it is not at all the fact that the conclusion is preordained. Indeed, a large point of the paper is that even assuming the entrepreneurship-risk link, we need further conditions to generate asymmetry in policy.

phosphorious 06.13.13 at 8:23 pm

In terms of journalistic practice, the phrase “Open the freezer” has gained some currency. Do a Google search; Howie Schneider at SUNY Stonybrook coined the ohrase, I believe. It is a reference to the situation resuklting from Hurricane Katrina. There were news stories of a walk in freezer full of dead bodies, even an interview with a national guardsman who was guarding the freezer. The reporters covering the story never actually opened the freezer , which turned out to be empty.

Made a good story though!

Sandwichman 06.13.13 at 8:38 pm

The Rasbotham Effect. The quality of the argument is not what is at stake. What matters is the frequency of repetition and the absence — or systematic ignoring — of counter arguments and refutations.

Dorning Rasbotham was an 18th century country squire and magistrate, whose unsubstantiated assertions are echoed incessantly by Anglo-American economists — most recently Jonathan Portes (U.K.), Stephen Gordon (Canada) and Casey Mulligan (Chicago).

Doug K 06.13.13 at 8:40 pm

Mark Thoma and Lane Kenworthy take the cuddly/cutthroat model apart at:

http://economistsview.typepad.com/economistsview/2012/09/will-american-innovation-slow-if-we-go-cuddly.html

Most noticeably, Finland and Sweden rank third and fourth in the world in innovation, the US is seventh.

http://www.weforum.org/reports/global-competitiveness-report-2012-2013

This is a generally sound way of attacking economics papers full of abstruse math based on fantasies – look at the actual data in the real world, make some simple back-of-envelope calculations, et voila, absurdities naked and shivering..

I should dearly love an exposition of

“in some sense exports its potential labor conflict ”

to clarify how the labor conflicts could possibly be exported.. labor, as is well known, does not enjoy the freedoms and liberties of capital.

Incidentally the spherical cows belong to physicists, not economists.

All models are wrong, but some are useful.

MattF 06.13.13 at 8:40 pm

Some of it is ‘confirmation bias’, particularly if you’ve rejected models that don’t prove the point you’ve set out to make. It’s easy to persuade yourself that you’ve proven things you believe to be true.

TF79 06.13.13 at 8:40 pm

I’m with afinetheroem, I find this post to be rather weak tea in regards to the specific criticisms of the Acemoglu paper. They make assumptions, with math, lol! If you really want to ding them for their “core” assumption, then it seems like you should probably take a few minutes to read the backing for that assumption. Because they aren’t “hiding” that assumption, it’s pretty clear from the intro that they are basing it on existing papers (see exerpt below). In fact, not only do they mention the point that Liberal Market Economies (LMEs) and Coordinated Market Economics (CMEs) can both spur innovation, but in potentially different ways, they cite two empirical papers surveying this argument.

So if you really want to make the point you’re making here, you should A) not force your blog readers to dig up the relevant text from the paper that discusses precisely the shortcomings you’re highlighting, and B) take a look at the empirical papers on innovation cited. Maybe ARV cited them incorrectly, maybe the evidence isn’t as clear as they make it sound, maybe there are some counter-empirical papers to this point. But that would tell us a lot more than LOLZ about spherical cows.

As to the more general point about economic reporting, I agree to a point (both for the reasons stated, and others), but I think this is a poor example of it. There are certainly other examples that fall into the “assume a can-opener” type of criticism (for example, “if we assume that markets never fail, then there are no market failures”)

“Our paper is related to several different literatures. First, the issues we discuss are at the core of the “varieties of capitalism” literature in political science, e.g., Hall and Soskice (2001) which itself builds on earlier intellectual traditions offering taxonomies of different types of capitalism (Cusack, 2009) or welfare states (Esping-Anderson, 1990). A similar argument has also been developed by Rodrik (2008). As mentioned above, Hall and Soskice (2001) argue that while both CME and LMEs are innovative, they innovate in different ways and in different sectors. LMEs are good at “radical innovation” characteristic of particular sectors, like software development,

biotechnology and semiconductors, while CMEs are good at “incremental innovation” in sectors such as machine tools, consumer durables and specialized transport equipment (see Taylor, 2004, and Akkermans, Castaldi, and Los, 2009, for assessments of the empirical evidence on these issues). This literature has not considered that growth in an CME might critically depends on innovation in the LMEs and on how the institutions of CMEs are influenced by this dependence. Most importantly, to the best of our knowledge, the point that the world equilibrium may be

asymmetric, and different types of capitalism are chosen as best responses to each other, is new and does not feature in this literature.”

Sandwichman 06.13.13 at 8:48 pm

There’s also an old anecdote about how many legs a cow has if you call its tail a leg.

Philip 06.13.13 at 9:01 pm

afinetheorem, how can making a claim about free-riding not be normative?

“while relatively backward countries can free-ride and choose cuddly reward structures safe in the knowledge that their impact on the long-run growth rate of the world economy (and thus their own growth rate) will be small.”

lemmy caution 06.13.13 at 9:20 pm

I guess it doesn’t really matter because they don’t actually use any real data in their model, but their discussion of the level of technology innovation in US and Scandinavian countries is horrible.

They apparently got their data from the world bank indicators for technology:

http://www.tradingeconomics.com/denmark/patent-applications-nonresidents-wb-data.html

http://www.tradingeconomics.com/united-states/patent-applications-nonresidents-wb-data.html

Researchers in R&D (per million people) in United States:

denmark – 6494.4

US- 4673.2

Research and development expenditure (% of GDP)

denmark- 2.9

US- 2.8

Scientific and technical journal articles

denmark- 5303.5 ( about 950 per million)

US- 212883.0 (about 670 per million)

nothing graph worthy in any of that. Which leads them to make the comparisons of what they call “Patent fillings per million residents at domestic office”.

filings by US residents at the US patent office per million

fillings by Denmark residents at the Danish patent office per million

They then create their graphs from this data.

What they don’t say is that the popularity of filing in the US patent office (as well as the european patent office (EPO) and international applications under the PCT) for both residents and non residents has exploded while the relative popularity of filing in the Danish patent office for both residents and non-residents has declined.

Danish residents file more patent applications in the USPTO:

2,059

http://www.uspto.gov/web/offices/ac/ido/oeip/taf/appl_yr.htm

than in the danish patent office:

1,634

http://www.tradingeconomics.com/denmark/patent-applications-residents-wb-data.html

Someone must have pointed out such problems to them because they go on say:

“Another plausible strategy would have been to look at patent grants in some “neutral” patent office or total number of world patterns. However, because US innovators appear less likely to patent abroad than Europeans, perhaps reflecting the fact that they have access to a larger domestic market, this seems to create an artificial

advantage for European countries, and we do not report these results.”

Which to me means they did check this out and unsurprisingly found some additional un-graph worthy information.

If there was more technological innovation in the US per capita than Scandinavian countries, I am sure their model would account for it though.

LizardBreath 06.13.13 at 9:32 pm

If you want to describe modeling based on bad assumptions because they’re easier to deal with, there’s always the “drunk looking for his keys under the streetlight because the light’s better there.”

x.trapnel 06.13.13 at 9:42 pm

The respected, top-department economists are using patent filings as a proxy for innovation would be funny if it weren’t so sad.

Zamfir 06.13.13 at 9:55 pm

Yeah. Patents might be up there with economics papers when it comes to hot air over substance.

John Quiggin 06.13.13 at 9:55 pm

Coming in very late, we really need a good replacement for “begging the question”. “Circular reasoning” is the best available, and probably good enough.

Sandwichman 06.13.13 at 10:04 pm

“what I need is something a bit more scalpel-like, a word or phrase or short description that captures the danger of thinking that self-consistent economic conclusions should lead us to believe in the real-world applicability of the assumptions.”

“Danger”? What do you mean “danger”? Here’s the flaw in YOUR assumptions, Clay. You are wrongly assuming that this kind of “easy [but false] knowledge” has no real-world applicability. Its real-world applicability is that it is glib and it can provide an appearance of evidence for questionable ideological positions.

It’s like “How to Lie with Statistics,” which was not meant as a recipe book. But see how economist Stephen Gordon applies the principle of “The Well Chosen Average” in a journalistic piece explaining “why you should care about productivity” at Maclean’s.

http://econospeak.blogspot.ca/2013/06/cheap-hustle-2-how-to-lie-with.html

Ronan(rf) 06.13.13 at 10:05 pm

I remember this paper, (as an economics-illiterate), when it came out, and remember the pushback it got immediately (and decisively)..isnt the problem more that it’s Acemoglu and Robinson’s narrative which gets bought? The ‘assumptions’ aren’t really here nor there, the question is why dont econ (*all*) journos just report the alternative perspectives as well?

Walt 06.13.13 at 10:06 pm

David K. Levine, who someone above referred to as “near autistic”, has a paper on the total worthlessness of patents as a measure of innovation. The paper has a model in which patents turn out to be bad…

Ronan(rf) 06.13.13 at 10:07 pm

..@43 + .. which is the point of the post, I guess

Bob W 06.13.13 at 10:11 pm

You lose me with your response:

“@finetheorem, what I disagree with is precisely this: “Reading economic theory means considering the steps of the proof, or the way the abstract assumptions combine together to generate the stated conclusion.â€

That is exactly what’s wrong with this paper, and with much journalism about economics. If the steps of the proof are mathematical, then the proof shows only that if the dominoes are placed right, then one push knocks them all down.”

The factual assumptions in the presentation have to stand on their own in terms of validity. But the steps of the proof are independently important. How you state and manipulate the assumptions in mathematical terms is important and may be correct or incorrect, independent of the validity of the assumptions. In this sense, the use of mathematics in economics is no different than, e.g., in quantum theory. It may be garbage in precludes a useful outcome of the analysis. But if it is not garbage in, the math becomes independently significant.

As an example from economics, have you considered Quiggin’s recent paper on Unawareness, Black Swans and Financial Crises? the math is to carry the argument forward in a rigorous manner. Not to establish the validity of the factual assumptions.

Bloix 06.13.13 at 10:14 pm

The thing is, the paper doesn’t claim to be proving that “cutthroat capitalism” is more innovative. It has a sort of feint in that direction when it compares patents per capita among the US and Scandinavian countries, but it doesn’t make any rigorous effort to prove it. The proof is about something completely different:

– assume that cutthroat capitalism produces more innovation and thus more growth

– assume that cuddly capitalism produces better living conditions for more people

– we can show that cuddly capitalist countries can free-ride on the cut-throat capitalists and thereby have almost the same growth that they do

So what we’re proving here is that the Scandinavian countries have almost the same rates of growth as the US because they’re parasitic free-riders, and we get there only by first assuming that cutthroat capitalism is more innovative.

But the bad journalists simply misunderstand the paper to prove that cutthroat capitalism is more innovative, which the paper never claims to be proving.

This is not to defend the paper, only to argue that the sleight of hand it engages in is quite a bit more sophisticated than simple begging the question.

Sandwichman 06.13.13 at 10:15 pm

“The respected, top-department economists are using patent filings as a proxy for innovation would be funny if it weren’t so sad.”

Back in the 1970s as an undergrad, I got a job as a research asst. for a geographer who wanted to use patent filings as a proxy for innovation. As I poured through the patent records one by one it became clear to me that MOST of the patents were for marketing gizmos that had NOTHING to do with basic technology.

The prof. was looking at innovation in the forest industry. Most of the patents in Canada had to do with different configurations for cutting and folding cardboard cartons for beer bottles/cans. I told him what I was finding but he didn’t want to know what the patents were actually for. He wanted the numbers. Apparently, you can do really smart things with numbers if you don’t know what they are numbers of.

Barry 06.13.13 at 10:16 pm

“indeed, in many ways, he is quite left-wing”

When saying this about an economist, it means – well, what does it mean?

Bloix 06.13.13 at 10:17 pm

And just to be more explicit:

There’s an ideological problem that needs to be solved:

If (as everybody knows) cutthroat capitalism (the US) is so much more productive than cuddly capitalism (Sweden), how can it be that the Swedish standard of living keeps pace with the US standard of living over time?

The paper provides the answer: Free riding.

That’s what the paper is actually about.

Metatone 06.13.13 at 10:19 pm

To the defenders of Acemoglu et al. – this paper has been debunked on so many levels, it’s embarrassing. Mark Thoma did the real world innovation piece, I posted a long review in comments to DA about his theoretical treatment of innovation (which he seems to have misplaced since then) and there are other smaller errors.

However, worst of all is the error in building on unrelated literature without understanding it. “Varieties of capitalism” does not, as a body of work, let you make the assumptions they did. Alas, that point seems beyond them, no matter how many people involved in said literature point it out to them.

UserGoogol 06.13.13 at 10:22 pm

Well, there’s begging the question and then there’s begging the question. Acemoglu and friends are not literally assuming their conclusion, but they’re assuming something awfully convenient for their conclusion and arguably about as controversial.

It’s like saying “The Bible is true because God would not allowed it to have been written if it was false.” God existing (and being the sort of god who gets upset when people say false things about him) and the Bible being true are two distinct statements, but using one to prove the other will be unsatisfactory to most non-believers.

PGD 06.13.13 at 10:29 pm

“Purely theoretical papers do have findings, but in a special sense that a journalist might want to explainâ€

No journalist should ever be writing a piece about a theoretical economics paper. I mean, come on. Part of the problem is that theoretical econ papers often write their abstract as though they are discovering something rather than playing with illuminating mathematical conjectures. But a journalist has no ability to evaluate this stuff or figure out exactly what’s illuminating about it or deceptive about it. They will be bound to present it as more conclusive than it is simply to justify writing about it.

Martin 06.13.13 at 10:32 pm

(The following metaphor is not original with me. I think I got it from an early book by Daniel Dennett but my memory could be wrong.)

You have to watch for the step of the argument where the magician puts the rabit in the hat.

(This only works if your students are familiar with traditional stage magic tricks where the magician pulls a rabit out of a top hat. I don’t know if this imagry is still current in popular culture.)

Sandwichman 06.13.13 at 10:33 pm

“The Bible is true because God would not allowed it to have been written if it was false.”

= “Economics is true because supply and demand.”

Ian S. 06.13.13 at 10:37 pm

Thanks, I too was quite shocked by this article, and its reception!

How about baked-in conclusions?

Or some variation around the idea of baking…

Ronan(rf) 06.13.13 at 10:39 pm

“No journalist should ever be writing a piece about a theoretical economics paper..”

Yep. The average journalist will never develop the technical skills to write coherently on these topics. Why not just report ‘the debate’, or go back to actually reporting/investigating/interviewing etc?..Hire a professional to write on complex topics or send your journalists to grad school

Pat 06.13.13 at 10:40 pm

@John Quiggin: “[W]e really need a good replacement for ‘begging the question’.” I suppose I’m rather a dead-ender on this and refuse to give up on the phrase, used properly. Analogously, I still feel rather entitled to the words “literally” and “ironic” notwithstanding their widespread abuse.

That said, “carjacking the question” has a certain flair.

Zamfir 06.13.13 at 10:52 pm

+1 for martin in 54. Putting the rabbit in the hat is exactly the metaphor we need.

Assuming a can opener is also good, but for something slightly different.

P O'Neill 06.13.13 at 11:06 pm

Other options for Clay’s original query include #jpepitch and yaddayadda economics.

roger nowosielski 06.13.13 at 11:12 pm

“Is there any label for this habit of camouflaging suspect assumptions while emphasizing obvious conclusions?”

Yes, presuming the rightness of motive (i.e., that the purpose is not to deceive), it’s called “scientism” — which is to say, the idea that sciences (economics in this instance) can stand on their own, there being no need for a philosophical bearing.

Tony Lynch 06.13.13 at 11:27 pm

Bootstrapping without any boots?

roger nowosielski 06.13.13 at 11:35 pm

But then again, how can we pull ourselves by our own bootstraps?

Rakesh Bhandari 06.13.13 at 11:42 pm

Perhaps only with the auxiliary assumption of social Darwinism would it even make sense to say that the innovation of smarter phones justifies the lives that austerity costs (Stuckler and Basu)?

Sandwichman 06.13.13 at 11:42 pm

Or disappear up our own…

Rakesh Bhandari 06.13.13 at 11:45 pm

justifies the loss of life that austerity causes

Rakesh Bhandari 06.13.13 at 11:54 pm

Is it so implausible to argue that today that “innovation” requires high levels of inequality?

If technological possibilities are few and thus the the likely rate of entrepreneurial failure is high, then VCs or CEOs will likely demand higher rates of return.

Assume innovation is carried out by entrepreneurs. If highly skilled labor can share in the rents enjoyed by technological monopolies, wouldn’t it take outsized rewards to motivate them to leave for a start-up and thus innovate?

If due to global competition, the extra profits from innovation are short-lived, then the extra profits have to be high to justify risky investments in innovation.

All this is to say. I am not sure the critique should be, first and foremost, that innovation is not tied to inequality. There is also the question of what price we should pay for innovation.

Lee A. Arnold 06.14.13 at 12:04 am

I think it would be easier to argue that U.S. innovation and percapita GDP should be much farther ahead of the pack, and the problem is the enormous risks for failure in the United States, because it doesn’t have much of a safetynet.

As I wrote under Mark Thoma’s later post (May 30, 2013), I see two problems with Acemoglu, Robinson, & Verdier’s assumptions. First, they do not appear to consider the relative size of the domestic populations and the domestic markets. “The division of labor is limited by the extent of the market.” Larger populations (ceteris paribus, and with good social capital) ought to have numerically larger instances of innovation. In addition to that, having a geographically larger domestic market means the domestic growth will be slightly faster. The availability of international trade will equalize the effect somewhat, but there are additional transaction costs involved to international trade, so how could it do so entirely?

The second problem is inside the theoretical premise of endogenous technological change. Many if not all scientists and artists start out, not from acquisitiveness for money or material success, but from curiosity about the world and about the human place in it. If the efforts of those people are hampered in life by less social protection, it may well result in less basic creativity. We already know that some U.S. physicists may move to Wall Street hedge funds in pursuit of lucre: they do not want to stay poor in physics, or else they have exhausted their creative impulse. On the Nordic side, the explosion in artistic and musical creativity recently has been phenomenal.

What needs to be explained is why “cutthroat capitalism” has been so obviously a pathetic schnorrer. The growth slowdown in the last 35 years in the U.S. probably has a few different causes, but one of them may be that the “leading role in the transformative technologies of the past several decades” was due to groundwork provided in the PRIOR, decades by a strongly-protected middle class, education, and U.S. government basic R&D, up until the Reagan revolution started to dismantle common sense.

hix 06.14.13 at 12:35 am

Dont blame the journalist or his education level. Grad school does not solve time constraints and or being forced to write what the editors thinks readers want to hear.

(Our journalists often do have Ph.Ds, that changes nothing)

hartal 06.14.13 at 1:06 am

So other countries not having to pay for the innovation off of which they free ride, they have become rich enough to pay for the social welfare that Americans do not themselves have, yet the people of these other countries then have the gall to look down upon Americans as barbarians for the incivility of their society. These were the same people who demanded American industry not protect itself even as America diverted money from its industrial sector to the defense of the Free World on which they all depended. The exploitation of the United States should stop; it becomes intolerable when coupled with the smug sense of superiority of Europeans.

Of course Americans could stop paying for innovation with inequality, but then the rate of growth would drop off in the US as well as everywhere else, paving the way for right-wing revolutionary middle class disaffection from any and all social welfare states. The destruction of the lives of the American poor is ultimately a small price to pay for the many welfare states that we still do have.

I think this is what A, R and V are arguing.

Tony Lynch 06.14.13 at 2:00 am

Roger @63: From the Stanford Encyclopaedia of Philosophy:

The fourth and fifth problems for reliabilism are of more recent vintage than the first three. The fourth problem is the bootstrapping, or “easy knowledge,†problem, due to Jonathan Vogel (2000) and Stewart Cohen (2002). Both Vogel and Cohen formulate the problem as one about knowledge, but it applies to justification as well. In Vogel’s version, we are asked to consider a driver Roxanne, who believes implicitly whatever her gas gauge “says†about the state of her fuel tank, though she doesn’t antecedently know (or have justification for believing) that the gauge is reliable. In fact, it is a perfectly functioning gas gauge. Roxanne often looks at the gauge and arrives at beliefs like the following: “On this occasion the gauge reads ‘F’ and F,†where the second conjunct expresses the proposition that the tank is full. The perceptual process by which Roxanne arrives at the belief that the gauge reads ‘F’ is reliable, and, given the assumption about the proper functioning of the gauge, so is the process by which she arrives at the belief that the tank is full. Hence, according to reliabilism, her belief in the conjunction should be justified. Now Roxanne deduces the further proposition, “On this occasion, the gauge is reading accurately.†Since deduction is a reliable process, Roxanne must be justified in believing this as well. Suppose Roxanne does this repeatedly without ever getting independent information about the reliability of the gauge (whether it’s broken, hooked up properly, etc.). Finally she infers by induction, “The gauge is reliable (in general).†Since each step she uses is a reliable process, the latter belief too is justified. With just a little more deduction Roxanne can conclude that the process by which she comes to believe that her gas tank is full is reliable, and hence she is justified in believing that she is justified in believing that her gas tank is full.

This entire procedure is what Vogel calls “bootstrapping,†and Cohen calls “easy knowledge.†Both claim that the procedure is illegitimate. After all, you can apply bootstrapping to a great many underlying processes, some reliable, some not. Every time, bootstrapping will tell you that the underlying process is reliable. So bootstrapping is itself unreliable. Since reliabilism licenses bootstrapping, reliabilism is in trouble; so Vogel concludes, at any rate. Another label for bootstrapping is “epistemic circularity.†Epistemic circularity is the use of an epistemic method or process to sanction its own legitimacy. In effect, Vogel is saying that reliabilism is mistaken because it wrongly permits epistemic circularity. Cohen does not pin the blame squarely on reliabilism.

shah8 06.14.13 at 3:37 am

I just have problems thinking of Swedish people as cuddly. Or thinking of Swedish history as one which a bunch of cuddly people got along for the good of all.

Sweden is a powerful state with a high standard of living and is a liberal society because they industrialized not that much later than UK and Net, and they never took on the sort of state directed capitalism characteristic of Russia, Germany, and Japan. Moreover, they were the Saudi Arabia of steel for much of the modern period, among other resource exports like timber. Since they had a rational political regime (’cause all the warmongers got killed off by Russians), the benefits were a little more distributed to the population at large, and the dissatisfied went off to America. In the sense that Nordic countries ever mooched off of any country, they mooched off of the UK in the 19th and 20th centuries. They certainly do not mooch off of US innovation. US demand, of course, but not US innovation. Any idiot with an awareness of Nordic technical prowess knows that they do innovate–in the areas where their companies are dominant. In fact the worst recent corporate disaster in Nordic companies has to do with Nokia dumping its own software for Windows’ disaster of an implementation of Windows8 for phones, not least of which, the waiting for as deployment was delayed.

Minimal introspection and knowledge of history makes the paper suspect pretty much before you get past the abstract. Cutthroat capitalism doesn’t generate innovation. If that was true, then Chinese people are already colonizing Mars and fermenting soybeans with Martian bacteria for a tasty snack. Cutthroat capitalism generates insecurity and destroyed assets in return for large pools of returns that are often not reinvested well because the social and economic institutions (which Acemoglu seems to care about) necessary for getting higher returns from renewed investment are often destroyed in the process of the original accumulation. Americans engage in cutthroat capitalism, where it’s capitalism for the little people, and socialism for the rich, and America can do this because America is freakin’ huge and relatively underpopulated and well watered. Slavery and dispossession made this nation, yo, and the Nordic countries never had American options, and their elites never could emulate Jay Gould and avoid getting hanged.

shah8 06.14.13 at 3:52 am

And while we’re on this topic, my personal hate favorite is Baumol Cost Disease. This thingie is true as it goes, like most economic concepts used and abused by ideological neoliberals. However, it’s never present in public discourse as anything other than a means to pathologicalize noneconomic activity. Teachers didn’t *use* to make good money, after all. Many teachers of old were women who had few options for careers. The rest were fringe characters barely able to teach at all, with a very few professors with good pay. The whole point of rising GDP and economic activity is to support what humans think of as important in life, though. The pay may rise, but that’s entirely appropriate, particularly if you’re not one of those creeps that love gold standard-like behavior and refuse to put enough money into the system. More than that, rising pay and rising numbers in the profession enhance living standards for everyone else as their demand helps prop up more obviously economic/profitable activity. Lastly, it’s almost aways focused on jobs little people have, and not the jobs rentiers have as their social titles.

That everyone, as a product of a richer society, is more heavily invested in–and is worth more, despite what profession they choose to exploit their talents in should be a big, honking clue about what this is about. Too many people getting uppity.

Cosma Shalizi 06.14.13 at 4:08 am

Noah Smith is actually on Shirky’s side of this one. (I haven’t read the paper in question.)

Lee A. Arnold 06.14.13 at 4:45 am

Ronald Coase is probably on Shirky’s side too: “You know, I saw a statement once of Niels Bohr, who is the originator of quantum mechanics, a very great man. He was always distrustful of formal and mathematical arguments. When people made such arguments, he’d always say, ‘Oh you’re just being logical; you’re not thinking.’ What we want to do is to move people from being logical to thinking. If you judge economists on the basis of their logic, they’re very good, I mean they’re probably— some of them—even better than the physicists, but they’re not thinking.” (Coase interview, 1997)

adam.smith 06.14.13 at 4:59 am

I don’t have a good phrase, but my lesson of the ART paper for journalists would not be “question the assumptions” when reading econ papers, but rather “focus on the empirical part of the paper, forget the theoretical model”.

In other words, journalists should be doing what Yglesias and Kenworthy (though he’s social scientist, but in this case a good journalist could have done the same) and to some degree Clay Shirky did: Look at the empirics of the paper and see if they’re plausible. In this case they’re really shaky and I think that’s the real problem with the paper. If there _were_ an observable innovation/equality trade-off in the real world, I don’t think ART’s attempt to explain it would be so bad.

Every econ paper makes simplifying assumptions, so criticizing those isn’t all that interesting. Actually understanding a model and providing a useful critique of the theoretical model – the work that Thoma did – requires a much higher degree of mathematical competency than I’d expect of most journalists. But while that part is really useful for the intra-economic debate – it’s the part that can lead to better models in the future – it’s really not very enlightening as a journalism project.

So if you really want a catch phrase, it would be “Skip the greek and go right to the graph” – where the graph, obviously, is representation of real empirical data, an not a simulation based on their model. In the case of the ART paper that means spending most of your time looking at section 1 and forgetting 2-5. Only if you find section 1 really convincing are the other sections even worth a look.

The same thing applies to the self-multiplication example. You don’t want to start going through a long set of mathematical derivations on why X^2 = X – and in fact, a mathematician could write a proof of this that looks correct to even reasonably math-literate people by hiding an assumption or a null multiplication. Instead, you just look at the empirics, point out that it’s not true for x=2 and you’re done. Every journalist who wants to report on economics should be able to do that.

peggy 06.14.13 at 5:29 am

@39

“using patent filings as a proxy for innovation would be funny if it weren’t so sad.”

I live in Boston where a start up hides under every rock and discussions of patent filing strategies take place at children’s birthday parties. It is so widely understood that patents are often unrelated to any expertise except for that of legal innovation that I wonder if these economists have ever met an entrepreneur. In the middle class social circles I inhabit, school, church, friends, almost every family has at least failed start up, or sometimes a successful one.

Do economists even avoid day care centers where the other parents might include scientists or engineers? MSU is renowned for robotics, Illinois Urbana is known for science. Maybe fresh water economists can’t swim that far.

In Boston, even the social organizations show a fair amount of creative intellectual energy. Government supported farmers markets pioneered on the East Coast in 1980. Feminist groups started in the mid 60’s and the New England Free Press published their writings, including “Our Bodies, Ourselvesâ€. The left wing philanthropy Resist has provided seed money to groups like the Vietnam Veterans against the War and OWS since 1967. Radicals such as myself enabled a protected space for the formation of the Union of Concerned Scientists across campus from where David Baltimore was winning his Nobel.

Does the economics profession postulate that creative people never group together, enjoy a similar outlook and often are kin? Possibly a disquisition on the interrelationships between water powered factory owners and abolitionists would be fruitful. Or maybe the steam engine and the Scottish Enlightenment.

hartal 06.14.13 at 5:31 am

They don’t deny Nordic countries innovate (just read their blog entry). They claim that the innovation there tends to be of an incremental sort, not the radical kind disproportionately produced in US. That conceptual distinction is found in the Schumpeterian literature (Rosenberg and Mowery, Christopher Freeman and Carlota Peretz); Nathan Rosenberg, sympathetic to Schumpeter, has expressed concern that the contribution of incremental innovation to total growth tends to be underestimated in the literature. Acemoglu and Robinson are Schumpeterians.

It seems that they are arguing that there are two possible equilibria–one the extant asymmetric one, the other one in which all countries suffer low-growth, cut-throat capitalism.

Only by Romney and the Tea Party holding back the redistributionist Democrats and the US thus continuing to be the radical innovation leader off of which others can free ride has the world been able to continue to enjoy the former solution, which results in higher overall global welfare.

I guess it helps that the poor who are sacrificed in the US are imagined to be disproportionately colored. Social Darwinism casts its shadow on this disturbing debate.

Boolean 06.14.13 at 5:34 am

How about “freakonomics?”

jonnybutter2 06.14.13 at 8:12 am

If (as everybody knows) cutthroat capitalism (the US) is so much more productive than cuddly capitalism (Sweden), how can it be that the Swedish standard of living keeps pace with the US standard of living over time?

The paper provides the answer: Free riding.

That’s what the paper is actually about.

The problem I see is about theory choice: there is no rational way to show how the authors chose the theory they were to ‘test’. They *started* with free riding, as Bloix @ #50 suggests (i.e. it’s an ideological problem needing to be solved). As a matter of logic (which does, after all, matter), you can support – or seem to support – any theory at all once you have it. This is where the ‘as everybody knows’ stuff comes in.

robotslave 06.14.13 at 8:17 am

Well, if we’re looking for words that describe economic analysis where the reasoning is sound but the premises are faulty, one that leaps to mind immediately is “Marxist.”

Which is to say, it is not only neoliberals who are guilty of this.

Perhaps when we want to refer to ideologically rooted economics, we could just call it “ideology-based economics?”

roger gathman 06.14.13 at 8:50 am

Long before the Acemoglu, Robinson and Verdier article, conservatives were advancing the argument that we needed to defend BigPharma’s higher prices in the U.S. because the rest of the world depended on the innovations of U.S. drug companies. Pay less for viagra and you won’t get the marvels of the miracle anti-malaria drug!

Of course, in fact, BigPharma is an excellent case of the distorting nature of patent monopolies and profit based innovation, since, notoriously, BP has not spent a fraction of the money to research anti-malarial medicines as it has spent to combat erectile dysfunction or male pattern baldness.

Here’s Megan McArdle making an argument that is the corollary of the Acemoglu one:

http://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2009/09/does-the-us-really-account-for-so-much-pharma-profit/24465/

It has almost the same structure: putting some control on drug prices would harm the profits of the drug companies, which in turn would lead to non-innovation in the drug field, hence freeloading Europe will become a hell (of, for instance, erectile dysfunction).

I think there should be a term for an argument that actually takes McArdle seriously. So instead of begging the question, how about just McArdlizing?

dax 06.14.13 at 9:09 am

“They claim that the innovation there tends to be of an incremental sort, not the radical kind disproportionately produced in US. ”

What radical kind has been disproportionatelyproduced in the US?

Francis Spufford 06.14.13 at 10:35 am

‘Assumption laundering.’

bianca steele 06.14.13 at 1:38 pm

Ronan @ 57: Yep. The average journalist will never develop the technical skills to write coherently on these topics. Why not just report ‘the debate’, or go back to actually reporting/investigating/interviewing etc?..Hire a professional to write on complex topics or send your journalists to grad school

I would guess that most journalists who write directly about technical papers aren’t reading the technical parts of the papers, but are reading the paper, the abstract, the press release, the academic press, comments from other academics–and then interviewing the writers about what they said, and publishing the results of the direct interview. So that simplifies things.

In other words, the suggestions in adam.smith@57 sound interesting, and can produce interesting results in the right hands, but I doubt enough people want to read what a reporter got from applying common-sense rules, as opposed to what the original writer thinks, for this to happen very much.

chris 06.14.13 at 1:40 pm

Assume innovation is carried out by entrepreneurs.

What if we instead assume innovation is carried out by people who love to innovate? There aren’t many of them and they’re a little weird by the standards of the majority, but they will apply whatever talents and resources they have to trying to make something new and better.

In a high-inequality society, most innovators will lack the resources to carry out their innovations successfully. (In theory venture capitalism could solve this, but VCs are unlikely to listen to a pitch from someone who is poor. Members of high-inequality societies tend to form opinions about each other that are heavily influenced by class, and generally, the rich hold the poor in contempt and will not believe that they could have good ideas.) In a low-inequality society, many more innovators will actually be able to innovate successfully. Presumably they won’t get super rich as a result, or it wouldn’t remain a low-inequality society, but they’re OK with that because they’re more motivated by the drive to innovate than by the money they might make off it. They might get famous — at least among aficionados of whatever field they are innovating in — even if they don’t get rich, which may or may not matter to them.

This leads to the direct opposite conclusion — it’s the VCs who are free riding off the innovators’ labors of love, and high income inequality will hamper innovators more than it will promote them — and the assumption required to get there seems, to me at least, at least as plausible if not more so. Gates innovated in the past and is rich in the present, but the idea that he was in it for the money all along is kind of hard to swallow, and the idea that Kernighan and Ritchie or Stroustrup or Torvalds or Wall were or are in it for the money is downright ridiculous.

Anarcissie 06.14.13 at 1:44 pm

In my experience of American technological business, innovation and innovators are often punished. It is sometimes called the ‘first over the wall’ effect, although a better analogy would be to imagine a variety of birds pecking at seeds in a field; if one is observed to find something good, larger birds rush in and shove the discover aside. Innovators do not exist in a separate social space; they mix with worker bees, predators and free riders (and many actors assume more than one role). The more severe the inequality in the community, the more important predation becomes and the more innovation becomes a guilty and dangerous pleasure. Even at Bell Labs, where management was relatively tolerant and benign, the invention of C and Unix had to be carefully concealed. It would have been absolutely impossible in most business situations.

All that I say is anecdotal, but I doubt if anyone who has been where I’ve been would describe things otherwise.

Luis Enrique 06.14.13 at 1:51 pm

“Second, we consider that effort in innovative activities requires incentives which come as a result of differential rewards to this effort. As a consequence, a greater gap in income between successful and unsuccessful entrepreneurs increases entrepreneurial effort and thus a country’s contribution to the world technology frontier.

If we assume that innovation requires income inequality, then we can conclude that innovation requires income inequality. QED.”

That’s unfair. The paper isn’t claiming to demonstrate innovation requires income inequality. You’re right, they are assuming “a greater gap in income between successful and unsuccessful entrepreneurs increases entrepreneurial effort and thus a country’s contribution to the world technology frontier”. Then they use that assumption to do something else (show that other countries can be better off by taking technological advances generated by innovate dystopias whilst having happier egalitarian societies themselves). You want to argue their results are a forgone conclusion once you’ve seen the assumptions, well maybe if you add in the assumptions that technology can be freely appropriate by others and that more egalitarian countries are happier. I think you need to add up 3 assumptions to reach their conclusion.

Economists – certainly Acemoglu – understand very well how conclusions flow from assumptions. I don’t see your homily about maths adds anything here. Some papers you could accuse of trying to hide how their conclusions rest upon dubious assumptions, but not this one. The authors make a very easy for you to see which assumptions lead where.

Acemoglu produces about two dozen papers a year

http://daronacemoglufacts.tumblr.com/

some are better than others. This one doesn’t seem to be particularly interesting, I agree, and it would probably fall apart with more realistic assumptions – which isn’t always true of papers that make unrealistic assumptions. There might be something to it – it’s not crazy to think the rest of the world does free ride off US innovation to some extent, and you might think the pace of US innovation has something to do with aspects of US society that are otherwise undesirable (capitalist bastards that grid the faces of the poor) meaning the rest of us can be nicer places to live but still use US origin tech.

Afiak, Acemoglu is described as relative left wing because some of this papers do things like show trade can hurt workers in the USA ( http://economics.mit.edu/files/8512 ) or that private firms may be worse than the government at providing things like healthcare and education ( http://www.nber.org/papers/w9802.pdf ). Plus interviews like this

http://fivebooks.com/interviews/daron-acemoglu-on-inequality

Henry 06.14.13 at 2:02 pm

The bit in Noah’s post about the way in which they assume away most of the risks in entrepreneurialism is equally important. More generally, I’ve read a lot of Acemoglu’s work (given his productivity,not all of it; nor even most). He and Robinson aren’t hacks. If I were to guess, I’d say that they have right-of-center priors, but a demonstrable willingness to shift those priors where there is strong countervailing evidence. However, this paper surely is not one of A&R(&V – whose work I don’t know)’s finer moments.

Cranky Observer 06.14.13 at 2:45 pm

In discussing innovation it is important to consider not only Bell Labs, where the pay was decent but the glamor & reputation might have been part of the remuneration, but Western Electric as well. WE was the stodgy manufacturing arm of AT&T that over the years developed hundreds of world-changing technologies through its own R&D; it’s engineers & scientists got ok pay & nice pensions but neither the Larry Ellison rewards nor the industry glory. How does the model account for the WE employees’ innovation?

Then there is the question of the motivation of Linus Torvalds & developers of various key open source applications, few of whom got rich from those efforts.

Cranky

Linus did move to California, so I guess there’s that…

Luis Enrique 06.14.13 at 3:14 pm

they aren’t trying to provide a complete model of innovation. it’s fine that the simple relationship they use leaves a lot that’s important in reality out. It’s not fine if the simple relationship they use isn’t even there at all, in reality.

Wonks Anonymous 06.14.13 at 3:25 pm

Here’s how journalists should discuss the paper: don’t. Clay seemed to demonstrate that he was over his head and should have simply delegated to folks like Thoma.

Bruce Wilder 06.14.13 at 3:26 pm

I don’t know that it matters what the authors’ priors might be; they are playing to an ideologically committed audience, which demands that its prejudices be satisfied.

I like the parable of watching for when the magician puts the rabbit in the hat, but the rabbit and the hat are not the main business of an article like this — the main business is the pretty assistant in the skimpy sequin number walking around and bending over. The intended audience, the committed ideologues, who can confer reputation by acclamation (really, murmurs of “interesting” or “important”, etc) are looking to have their resentful political beliefs confirmed. (“See, I knew it, Swedish socialism only seems to work; it’s free-riding on the real work being done by the real innovators — John Galt is an American!”)

I’m with Luis Enrique, in that I don’t think it is fair to imply that they are trying to hide the putting of the rabbit into the hat. It seems to me that they are pretty upfront about how they are assuming their conclusions. That would matter, and would be a point of valid criticism, only if their essential argument was being expressed mathematically. It’s not. It is only being decorated with math, here. Lighting the stage to show off the babe in the sequins.

The real argument is exactly as advertised; or, it is the advertisement. As Luis Enrique summarized:

except I might quibble a bit with the “undesirable” part. The “undesirable part” in this case is the gargantuan paydays of CEOs, private equity investors, etc. — clearly “desirable” indeed for some powerful people, who, not incidentally, give big bucks to business schools and the like. But, Acemoglu plays a liberal with a conscience in this little vaudevillian morality play, precisely to add credibility with a precisely modulated tone of regretfulness to this rationalization for what is, at bottom, Ayn Rand’s view of the world.

The core argument is exactly what it appears to be: a substance-free bit of airy-fairy handwaving in favor of a fable of moral causality, a latter-day Allegory, in which Virtue Triumphs. The magician purporting to do a trick with maths is the distraction; the girl in sequins — Virtue — is the actual star. In service of the telling the moral fable, Innovation is conveniently distinguished Big (disruptive) and Small (incremental), and the Sacrifice of the little people is given a supporting role.

There’s a lot of this in policy economics. The Confidence Fairy in macro takes strength from this kind of dementia. Shah8 complains of Baumol’s Cost Disease, a classic paper where the math actually did complement the exposition, but the importance that paper assumes now is, as Shah8 says, all about the moral derived, about the undesirability of too much equality. Barro’s Ricardian Equivalence, on the math, a fundamental result or a triviality, depending on your depth of insight, is famous not because of what the math proves, but because of the moral weight the hand-waving around it seemed to give to the determined wish of committed ideologues, that fiscal policy be found self-defeating.

Fama’s Efficient Markets Hypothesis became one Quiggin’s Zombies, animated by the spirit of this ideological determination to see Economics as a Pilgrim’s Progress. The original paper is quite an elegant methodological argument for how to form a null hypothesis in doing certain kinds of research on prices in financial markets, but it walks the earth as a Zombie, standing for the Proposition that Markets are Efficient and Market Prices are Right, and No Man can rightly say, Otherwise. As economics, the Zombie is absurd — a cartoon caricature, one would think would be rejected out-of-hand. And, it is the audience, not authors, that accomplishes this feat, so, if you want fame and reputation as an economist, you cater to it, in some case only half-consciously I suspect, reinforcing the cycle.

This is a degenerate research program in what I dearly hope is the end stage.

Bruce Wilder 06.14.13 at 3:33 pm

My short answer, for those demanding shorter comments, is that the math is a skeuomorph, bolted on to a moral allegory.

Anarcissie 06.14.13 at 3:38 pm

@91 — I don’t think it’s fine if the simple relationship is actually a minor aspect of the situation and is also heavily freighted with rightist ideology. It’s not fine with me, anyway.

Lee A. Arnold 06.14.13 at 3:42 pm

It could even go the other way. Maybe the U.S. innovates in more tacky tchotchkes than the rest of the world, and in more advertising to sell the junk, because the entrepreneurs are afraid of not being able to pay for healthcare and their kids’ schooling. It could be that cutthroat capitalism is a total blight, not just a partial malfunction.

Zamfir 06.14.13 at 3:59 pm

Bruise Wilder says:And, it is the audience, not authors, that accomplishes this feat, so, if you want fame and reputation as an economist, you cater to it, in some case only half-consciously I suspect, reinforcing the cycle.

This. As you note, the Acemoglu article itself is open about what it does. It might be a tad shoddy, but it was probably written in good faith, just a thought experiment worked out. The problem starts when others mention its conclusions while ignoring the circularity.

In rabbit terms, the authors are not the magician. They are the way to slip in the rabbit.

Bruce Wilder 06.14.13 at 4:11 pm

The reality of the last 20 years or so is the dominance of rentiers, financialization and disinvestment.

Cutthroat capitalism would be a blessing beside the reality of vampire squid capitalism, inventing new forms of usury, ways to patent genes and circumvent the tax laws.

Sandwichman 06.14.13 at 4:58 pm

Bruce Wilder: “it is the audience, not authors, that accomplishes this feat, so, if you want fame and reputation as an economist…”

Yes, indeed. As Dorning Rasbotham wrote, “a cheap market will always be full of customers.”

Bruce Wilder 06.14.13 at 5:41 pm

As others have pointed out, if there’s sleight-of-hand involved, it is in keeping “the well-known incentive-insurance trade-off” in highly abstract, airy-fairy land, where its alleged correspondence to reality can be kept safely away from attachment to actual mechanisms and concrete phenomenon. As Henry @ 89 points out, Noah spots this kind of sleight-of-hand.

If, for example, instead of counting patents, you started looking at what the patents were for, or what their role was in industrial or commercial rivalry, you might begin to suspect that they were evidence not of cutthroat capitalism, but of incumbents forming a corporate oligarchy to protect their rents and eliminate any risk. Or, you might wonder what the virtue was, exactly, behind the innovation of, say, Starbucks. You want the abstractions to remain pretty bubbles floating above the earth, not tethered to anything specific, which might lead to someone else coming along and spoiling the catechism.

It wasn’t always this bad. Modigliani-Miller, a foundational paper for financial economics, uses algebra to actually make the core argument, and its algebra is perfectly accessible to anyone, who had the subject in high school. My old teacher, Harold Demsetz, whose political attitudes placed him to the right of Attila the Hun, could make profound arguments with simple, analytic geometry, and, yes, English! He wrote a brilliant analytic rationalization for public utility regulation, partly, I think, out of intellectual pride — he wanted to demonstrate that he was smarter than Galbraith. Axel Leijonhufvud, the last of the Keynesians, who dominated the 1960s, still gives talks and they stand out amazingly for their clarity and density of insight — I saw something the other day, where he pointed out how TARP and similar programs disguise the transfer from taxpayer to financial institutions, and it wasn’t some esoteric foo-foo no one could hope to follow intuitively.

Bruce Wilder 06.14.13 at 5:45 pm

Sandwichman @ 99

Since it’s economics, some reference to Gresham’s law would be appropriate; when the profession overvalues one currency (analytic theorizing and thought experiments) and undervalues a potential competitor (the study of actual institutions and mechanisms), the bad drives out the good.

Ian S. 06.14.13 at 6:01 pm

I would like to promote Francis Spufford’s ‘assumption laundering’ (#84).

Rakesh Bhandari 06.14.13 at 6:17 pm

The rate of entrepreneurial failure and the rate of the failure of large-scale projects within big corporations are very high and will increae if there is in fact a closing down of technological possibilities; the talent that could make a start-up successful has to be coaxed away from high-paying jobs with big private companies or as University Professors with the promise of small fortunes; and the profits of innovators are easily whittled away given the possibilities of reverse engineering. Maybe I drank the Kool Aid of Silicon Valley growing up there, but that is how it appeared to me.