I have a coincidence to report. This morning, right before Kieran’s post went up, I was scanning (see this post, concerning my new hobby) selections from Russell Lynes’ classic essay “Highbrow, Lowbrow, Middlebrow”, the inspiration for the Life chart on brows. Here is how Lynes tells the story in a (1979) afterword to his book, The Tastemakers: The Shaping of American Popular Taste [amazon], which is an out-of-print minor classic, if you ask me.

Four years before this book was published [in 1955], Chapter XVII, “Highbrow, Lowbrow, Middlebrow,” appeared in Harper’s Magazine, of which I was then an editor. This chapter was written before any of the rest of the book, but it was written because of it. I thought that if I was going to write about tastemakers, I should define their quarry, and on one of several attempts to write an introductory chapter to the book, I devoted a couple of pages to highbrows, lowbrows, upper and lower middlebrows. I showed this draft to Katherine Gauss Jackson, a colleague of mine at Harper’s, who said, “You’ve got the essence of a piece here. Why don’t you write an article on brows?” So I did, and it appeared as the lead article in the February 1949 issue of Harper’s. Several weeks later Life magazine, which was at the time “the king of the visual media,” did an article about my article and published a pictorial chart illustrating the several “brow levels” of American taste at that time. Since then this article (later the chapter only slightly revised) has had an independent life of its own, and though I invented none of them, the words highbrow, lowbrow and middlebrow, with its subdivisions into upper and lower, have become part of the language of taste along with “tastemakers,” which was, so far as I know, my coinage.

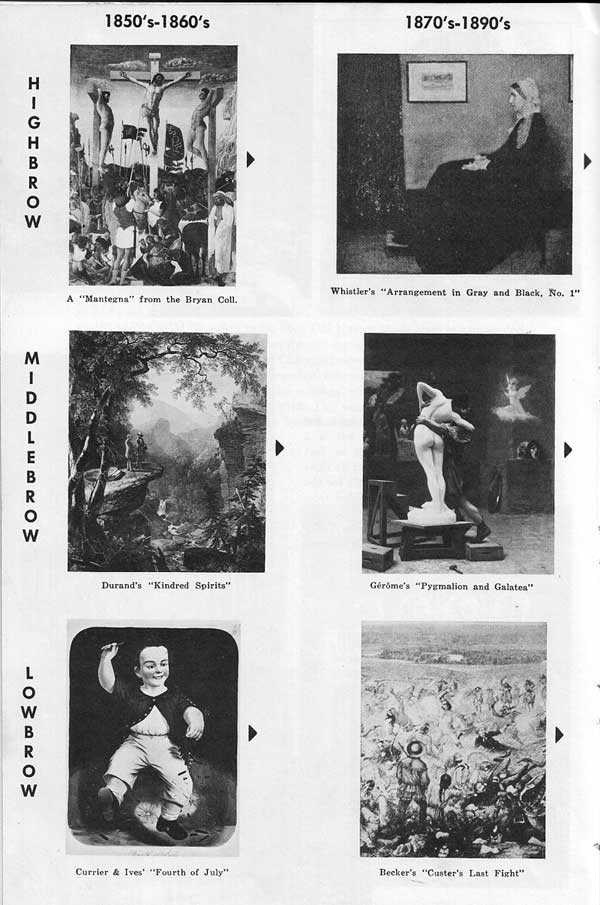

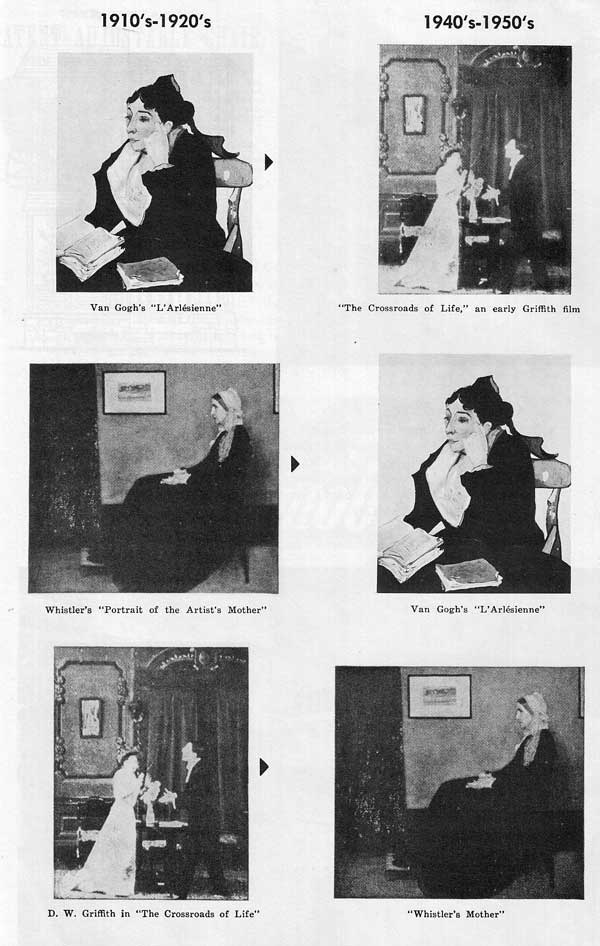

I can think of no better way to indicate the changes in taste that have occurred in the last quarter of a century than to reproduce here the Life chart, in which I had the controlling hand, and to note what has happened in the interim …”

Lynes concludes thusly:

As I look at the chart, which a Life editor and I concocted over innumerable cups of coffee years ago, it strikes me, as it must you, that what was highbrow then has become distinctly upper middlebrow today. The rate of change, indeed, is about the same as that which is demonstrated in the chart showing what happened between the 1850S and the 1950S [I’ll reproduce these charts below]. Who regards an Eames chair as highbrow now? Or ballet, or an unwashed salad bowl or a Calder stabile? They have all become thoroughly upper middlebrow, and what was upper has become lower. Only the lowbrow line of the chart makes spiritual if not literal sense. Today television would find itself at all levels of the chart in ways, as we have noted, too obvious to define. The “pill” has taken the glamor out of Planned Parenthood as an upper middlebrow cause, and Art and The Environment are now their causes instead … and so on. Even if the shapes of the pieces have changed, and the board looks quite different, the basic rules seem to me much the same as they have been since Andrew Jackson Downing set about in the 1840s to make our forebears lead harmonious lives in tasteful surroundings.

“Highbrow, Lowbrow, Middlebrow” is a fun read. When it comes to brow-flexing, to hold back the forces of evil, it’s a tough call whether the prize goes to Sammo Hung, for his role as Longbrow in Zu: Warriors of the Magic Mountain (1983), or to Clement Greenberg for his role as Highbrow, getting quoted saying this sort of thing: “It must be obvious to anyone that the volume and social weight of middlebrow culture, borne along as it has been by the great recent increase in the American middle class, have multiplied at least tenfold in the past three decades. This culture presents a more serious threat to the genuine article than the old-time pulp dime novel, Tin Pan Alley, Schund variety ever has or will. Unlike the latter, which has its social limits clearly marked out for it, middlebrow culture attacks distinctions as such and insinuates itself everywhere …. Insidiousness is of its essence, and in recent years its avenues of penetration have become infinitely more difficult to detect and block.”

Lyne is bemused by such stuff:

The popular press, and also much of the unpopular press, is run by the middlebrows, and it is against them that the highbrow inveighs.

“The true battle,” wrote Virginia Woolf in an essay called “Middlebrow” (she was the first, I believe, to define the species) lies not between the highbrows and the lowbrows joined together in blood brotherhood but against the bloodless and pernicious pest who comes between. . . . Highbrows and lowbrows must band together to exterminate a pest which is the bane of all thinking and living.”

Pushing Mrs. Woolf’s definition a step further, the pests divide themselves into two groups: the upper middlebrows and the lower middlebrows. It is the upper middlebrows who are the principal purveyors of highbrow ideas and the lower middlebrows who are the principal consumers of what the upper middlebrows pass along to them.

And we’re off! But you should probably start by reading the original Woolf essay (really, a letter), which some months ago my friend Josh Glenn very kindly and shrewdly and thoughtfully posted on his site, Hilo, which is all about this stuff, and then some. Here is Woolf, coining the term:

Lowbrows need highbrows and honour them just as much as highbrows need lowbrows and honour them. This too is not a matter that requires much demonstration. You have only to stroll along the Strand on a wet winter’s night and watch the crowds lining up to get into the movies. These lowbrows are waiting, after the day’s work, in the rain, sometimes for hours, to get into the cheap seats and sit in hot theatres in order to see what their lives look like. Since they are lowbrows, engaged magnificently and adventurously in riding full tilt from one end of life to the other in pursuit of a living, they cannot see themselves doing it. Yet nothing interests them more. Nothing matters to them more. It is one of the prime necessities of life to them — to be shown what life looks like. And the highbrows, of course, are the only people who can show them. Since they are the only people who do not do things, they are the only people who can see things being done. This is so — and so it is I am certain; nevertheless we are told — the air buzzes with it by night, the press booms with it by day, the very donkeys in the fields do nothing but bray it, the very curs in the streets do nothing but bark it — “Highbrows hate lowbrows! Lowbrows hate highbrows!” — when highbrows need lowbrows, when lowbrows need highbrows, when they cannot exist apart, when one is the complement and other side of the other! How has such a lie come into existence? Who has set this malicious gossip afloat?

There can be no doubt about that either. It is the doing of the middlebrows. They are the people, I confess, that I seldom regard with entire cordiality. They are the go–betweens; they are the busy–bodies who run from one to the other with their tittle tattle and make all the mischief — the middlebrows, I repeat. But what, you may ask, is a middlebrow? And that, to tell the truth, is no easy question to answer. They are neither one thing nor the other. They are not highbrows, whose brows are high; nor lowbrows, whose brows are low. Their brows are betwixt and between. They do not live in Bloomsbury which is on high ground; nor in Chelsea, which is on low ground. Since they must live somewhere presumably, they live perhaps in South Kensington, which is betwixt and between.

The puzzle about where the middle-brows can possibly live has been pursued down the decades to this very day. In the very best and most thoughtful book on the subject ever written – that would be Carl Wilson’s Celine Dion’s Let’s Talk About Love: A Journey to the End of Taste (33 1/3) [amazon] – the author quotes a baffled British critic, wondering where all the Celine Dion fans can possibly live. “Wedged between vomit and indifference, there must be a fan base: some middle-of-the-road Middle England invisible to the rest of us, Grannies, tux-wearers, overweight children, mobile-phone salesmen and shopping centre-devotees, presumably.”

But I promised you Lyne’s original, pre-Life charts. Here they are. (The one on the bottom is supposed to be on the facing page. So the top level is high, the middle middle and the bottom low. Obviously.)

{ 145 comments }

kid bitzer 10.20.09 at 6:11 pm

in shaw’s 1916 ‘pygmalion’, doolittle is already complaining about ‘middle-class morality’, the implication being that both high and low are united in libertinism, with only the stodgy and unimaginative middle opposed.

Keith 10.20.09 at 7:55 pm

The lowbrows and highbrows hate the middlebrows because the middles take the best parts of each of their respective cultures and do the unthinkable: they mix them. When confronted by middlebrow culture, lowbrows feel cheated, because they have to wrestle with highbrow stuff they don’t understand because it’s intellectual. The highbrows feel sullied, because their beloved canon is cavorting with buffoonery and thus lowered in stature.

Xanthippas 10.20.09 at 9:10 pm

Wonderful! I can’t even begin to explain why this is so fascinating to me, which means I probably should start by reading all of these articles and going from there.

Substance McGravitas 10.20.09 at 9:19 pm

This thread needs a Paul Fussell mention too. Prole jacket gape: avoid it.

kid bitzer 10.20.09 at 9:31 pm

incidentally,

“Here is Woolf, coining the term:”

if the term you refer to is “middlebrow”, then the oed assures me that it was in fairly common usage (punch, observer) throughout most of the decade previous to her letter.

she may have been the first to “define the species” in the precise terms she used, or to describe it as fully as she does in that letter. but the following makes it clear that she was not the first to apply that term to that population:

1925 Punch 23 Dec. 673/3 The B.B.C. claim to have discovered a new type, the ‘middlebrow’. It consists of people who are hoping that some day they will get used to the stuff they ought to like.

pretty good concise definition, i’d say. (though both for euphony and for accuracy i’d emend to “hoping that some day they will get used to the stuff they think they ought to like.”)

Gareth Rees 10.20.09 at 10:56 pm

Isn’t this low/middle/highbrow distinction a way of talking about social class as if it were a form of taste (and therefore an issue of personal choice rather than economic necessity)?

It seems clear from the Woolf quote that she’s using “lowbrow” to mean “working class”—”Since they are lowbrows, engaged magnificently and adventurously in riding full tilt from one end of life to the other in pursuit of a living, they cannot see themselves doing it”—in other words their need to earn a living by manual labour means that they don’t have the time and money for the artistic pursuits of the middle and upper classes.

Similarly, in the Life magazine classifications, the “lowbrows” wear old army clothes, sit on mail-order furniture and watch cheap movies because they don’t have the money for tweed suits, designer furniture and tickets to the ballet.

Substance McGravitas 10.20.09 at 11:12 pm

David Hockney’s iPhone paintings. That seems to me to be some fairly pure middlebrow right there.

Xanthippas 10.20.09 at 11:28 pm

Isn’t this low/middle/highbrow distinction a way of talking about social class as if it were a form of taste (and therefore an issue of personal choice rather than economic necessity)?

That is the most natural reading, based on Woolf’s essay (which to my mind can come off as a bit condescending.) But based solely on the reading I’ve done pursuant to this particular post, that’s not all there is to it. I found this Josh Glenn essay via his site Hilowbrow.com, and I think it explains what’s going on here in a manner that avoids a focus on class. And he more fully develops Woolf’s dislike of the “middlebrow” using modern examples that we can relate to more easily.

andthenyoufall 10.20.09 at 11:55 pm

“In whatever company I am I always try to know what it is like — being a conductor, being a woman with ten children and thirty–five shillings a week, being a stockbroker, being an admiral, being a bank clerk, being a dressmaker, being a duchess, being a miner, being a cook, being a prostitute.”

That’s Woolf – Woolf may have been referring to those dreadful lower-class stockbrokers, admirals, and duchesses, though. And you see that on the Life chart the highbrows eat plain salads and use industrial equipment as dishes?

John Holbo 10.21.09 at 12:15 am

“1925 Punch 23 Dec. 673/3 The B.B.C. claim to have discovered a new type, the ‘middlebrow’. It consists of people who are hoping that some day they will get used to the stuff they ought to like.”

Thanks. I had been taking Lynes word for it that Woolf was actually the originator of the term.

Jon H 10.21.09 at 12:25 am

Is that right? The Griffith movie went from lowbrow to highbrow?

Xanthippas 10.21.09 at 12:50 am

Actually Gareth, Josh does a much better job of explaining the non-class nature of lowbrow, middlebrow and highbrow in his comments to this particular post. And bonus, it’s much more concise than the article I link to above!

Emma 10.21.09 at 1:04 am

Is it just me, or is there a Bourdieu-shaped hole in this discussion?

nnyhav 10.21.09 at 1:40 am

From The Real Frank Zappa Book:

“Songs written with one idea in mind have been known to mutate into something completely different if I hear an ‘optional vocal inflection’ during rehearsal. I’ll hear a ‘hint’ of something (often a mistake) and pursue it to its most absurd extreme.

“The ‘technical expression’ we use in the band to describe the process is: PUTTING THE EYEBROWS ON IT.” This usually refers to vocal parts, although you can put the eyebrows on just about anything.

“After “the eyebrows,” the ultimate tweeze inflicted on the composition is determining The Attitude with shich the piece is to be performed. The player is expected to comprehend The Attitude, and perform the material with The Attitude AND The Eyebrows, consistently, otherwise, to me, the piece sounds ‘wrong.’“

Kieran Healy 10.21.09 at 2:17 am

What John is saying is that while I was reading the Life Magazine version on Google Books, presumably while eating a donut or something, he was scanning in Lynes’ original essay, listening to Philip Glass and not cleaning out his salad bowl.

nick s 10.21.09 at 4:40 am

Isn’t this low/middle/highbrow distinction a way of talking about social class as if it were a form of taste?

To some extent, though as Emma notes in comment 13, M. Bourdieu is your friend in that department.

Emma 10.21.09 at 5:26 am

Thanks Nick, I was beginning to worry. While it is a long time since I read Bourdieu’s Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste, I can’t think of a book that gave me more ‘aha!’ reactions in the interim. Xanthippus, if you find all this fascinating, you really need to read that book. What Bourdieu lays out is how the judgement of taste and social class are intimately interlinked, and used both for policing the boundaries, and for displaying them. Great stuff, and I always thought it explained quite as much about the academic subcultures I was inhabiting at the time as it did about any other subculture. In fact, B. takes such subcultures as his subject quite explicitly.

John Holbo 10.21.09 at 6:46 am

The Carl Wilson book is very Bourdieu-ish. I don’t think it is right to say that either Woolf or Lynes is missing the boat (especially not Lynes). The whole point of the term ‘the tastemakers’ is to indicate the existence of a class of people whose judgments of taste and social class are intimately interlinked, and who police and display the borders.

Chris Bertram 10.21.09 at 7:00 am

Something a bit too content driven about all this …. the chart has some of the objects of consumption moving row over time. But this ignores the possibility that the same object may sit in two rows simulaneously but be distinguished by the manner of its consumption (or the attitude of the consumer to it). Cf, the ironic gnome:

https://crookedtimber.org/2005/07/11/the-ironic-gnome-rule/

alex 10.21.09 at 7:43 am

*Sigh* the bourgeoisie just can’t get any love, can they? Is it beyond anyone to point out that for a ‘highbrow’ avant-garde elite to despise middling strivers while maintaining a dutiful respect for the echt qualities of good, honest working-class folk who know their place is not so much a cliché as almost the entire history of the relation between class and taste in the west for the last 250 years at least? You can laugh at it, but you probably also live by it. Nosce te ipsum, dude.

Henri Vieuxtemps 10.21.09 at 8:47 am

people who are hoping that some day they will get used to the stuff they ought to like

IOW, a phony. Didn’t Moliere thoughtfully ridicule them back … eh… something like 300 years ago?

bad Jim 10.21.09 at 8:57 am

Bah. One cigarette, one Orionid. A clear night and nearly no cosmic debris.

When we use “bourgeois” to indicate a less than elevated taste we emphasize that we’re not talking about socioeconomic status, or else that we’re so far outside the Marxist framework that our distinctions are more likely to confuse than clarify, though if we’re attempting to order everyone along a single dimension a certain amount of confusion is necessary to keep the conversation interesting.

Taste is splintered across multiple dimensions. Start with Snow’s two cultures and keep splitting through the cultural revolutions of the twentieth century. The shibboleths that divide two nearly identical groups eventually sound like common group identifiers to more distant crowds.

John Sladek described a conservation at a party between a professor and a student discussing respectively Rodin and Rodan. Life is a tossed salad of labels like hip and square, hot or not, high or low, in and out. It’s not just a matter of finding out what you most enjoy; you also have to know what your nearest and dearest are talking about.

Which of these two is more elite: a new model for the beginning of life or a reminder that tomorrow’s Great Performances on PBS features the LA Phil with a new work by John Adams?

alex 10.21.09 at 9:00 am

Ah yes, Moliere, that great example of a man born to his position and content to remain there… Not as bad [or good?] a climber as Beaumarchais, but running him close.

John Emerson 10.21.09 at 9:11 am

The Radical Middle Class: Populist Democracy and the Question of Capitalism in the Progressive Era in Portland, Oregon, Robert D. Johnston, Princeton, 2003.

Christopher Lasch touched on the culture wars as far back as the WWI era America in “The New Radicalism in America”. A lot of the American left of that time was pretty corny, whereas the cultural left was often apolitical, ultra-leftist and effectively apolitical, or right-wing. Elitist liberalism goes back to the WWI New Republic of Walter Lippmann, who turns out to be (ta-da!) the grandfather of neo-liberalism (Mirowski: “The Road from Mont Pelerin”).

When H. L. Mencken, the leader of the liberated elite, turned out to be a Roosevelt-hater who had trouble making up his mind about Hitler, it shouldn’t have been a surprise — he was a Social Darwinist Bourbon Democrat of the Grover Cleveland type who hated all moralism, especially the silly idea of social justice.

Emma (the first one) 10.21.09 at 9:16 am

As I recall, Bourdieu was all over taste and class being splintered across different dimensions, with the effects of cultural capital complicating things further. Also the ironic appreciation of both low and high culture. As for learning to like what you think you ought to, one thing that Distinction explained for me, which years of thinking about it had failed to explain, was my then parents-in-law and their continual house redecoration. They were working class made good, going from labourers in East London to university academics in Australia. Their rise through levels of class and cultural capital was quite dizzying, and their ‘habitus’ and taste had not kept up. Once established in Australia, though, they made friends in their new milieu, and as a result their house, decorated to their taste, looked odd to them just about every year, for well over a decade. It got more like their friends’ houses, and much less like the family’s back home. And all that work, repainting and recarpeting, then polishing the floorboards, chucking out the net curtains, changing the light fittings. Not just to new versions of the old ones, like my parents, but a completely new aesthetic every time. Taste is more than books and music.

alex 10.21.09 at 11:10 am

But then, Emma, some might argue that that practice is just weird. Or is it only hoity-toity academics [like me, but I admit not like some of my fashion-victim colleagues] who can even dream of signalling their status by affecting to like the stuff they like, and to hell with it?

Tom Hurka 10.21.09 at 11:30 am

#8: Woolf is just “a bit” condescending?

John Emerson 10.21.09 at 11:33 am

The European high bourgeoisie was wound way too tight. Austen’s oafish, stupid gentry were at least able to kick back and chill.

ajay 10.21.09 at 1:13 pm

Again, confusion between wealth, class and taste; it’s perfectly possible to be rich, lower-class and lowbrow, or to be poor, high-class and highbrow (highbrow culture isn’t utterly out of reach of the poor; a ticket to the opera costs less than a seat in the cinema in central London, and the art galleries, unlike the clubs, are free).

Josh Glenn 10.21.09 at 1:15 pm

Over at Hilobrow.com — thanks, John, for the link — we agree with Bourdieu that aesthetics and lifestyle choices aren’t entirely independent of social class. Though (along with Carl Wilson) we reject the reductionism of his Distinction, we do rely on Bourdieu’s notion of the “disposition” (a tendency to act in a specified way, to take on a certain position in any field) and the “habitus” (the choice of positions in a field, according to one’s disposition). We’ve named and located 10 bourdieuian dispositions — 4 heimlich (Highbrow, Lowbrow, Neo-Aristocratic (Anti-Lowbrow), Quasi-Populist (Anti-Highbrow)); 2 gemütlich (High Middlebrow, or what Dwight Macdonald called Midcult; and Low Middlebrow, which Macdonald, following Adorno, called Masscult); 2 unheimlich (Nobrow, not to be confused with John Seabrook’s confused use of the term; and Hilobrow, our own coinage); and then there’s Unbrow, which Van Wyck Brooks confusingly called Lowbrow. There are various habituses possible within each of these dispositions, but since the mid-17th-century, these dispositions have formed into an invisible matrix of influence.

Our hypothesis is that the 4 heimlich dispositions formed in the mid-17th century and after because of Spinoza and the so-called Radical Enlightenment. Before that time, Highbrow and Lowbrow were united, e.g., in a figure like Shakespeare. For two centuries after this Shevirat HaKeilim-like moment of shattering, Highbrow and Lowbrow remained fond of one another, copacetic and complementary; but as recounted by historians like Lawrence W. Levine, in the late 19th century a wedge was driven between High and Low. Virginia Woolf’s essay is a lament about this suddenly widening gap; unlike those intellectuals of her time who celebrated Middlebrow for bridging High and Low, she blamed Middlebrow for the divide. Writing a decade earlier than Woolf, Van Wyck Brooks also deplored what was happening to Highbrow as it lost contact with Lowbrow. However, Brooks made two major errors: he confused Lowbrow with Unbrow (philistinism), and he called for Middlebrow to close the divide.

Whence Middlebrow, the uncanniest of guests? We’re still trying to track it down — we’re pretty sure it existed before it was named in the Twenties. It might have been born in the very late 19th or very early 20th century, per Woolf and Brooks. I think Christopher Lasch is likely analyzing the disposition High Middlebrow — though he mostly isn’t discussing taste — in his The New Radicalism in America, 1889-1963. But in “Masscult & Midcult,” Dwight Macdonald blames Low Middlebrow on the industrial revolution, and it traces its origins back to mid-18th-century England. At Hilobrow.com we’re interested in tracking Middlebrow’s origins, but the critical thing is our discovery of its true role and position within the matrix of modern dispositions: Middlebrow does not mediate between Highbrow and Lowbrow; and therefore it should not be championed by those who are attempting to champion social mobility (i.e., from lower to upper class) in the sphere of culture. Lynes was misguided in this effort — and, as I mentioned at Hilobrow.com the other day, so are Andrew Ross, Susan Jacoby, A.O. Scott, the author of a recent Chronicle of Higher Ed essay titled “Confessions of a Middlebrow Professor,” and even my friends Alex Beam (author of a recent history of the Great Books series) and Carl Wilson. Despite what sounds — to our ears — like her snobbery, Woolf was dead-on when she claimed that Middlebrow was only making it more difficult for Highbrow and Lowbrow to reunite; and Macdonald and Adorno (also branded as mandarins) were also correct about this. Where does Middlebrow sit on the matrix of modern dispositions — and where do all these other “brows” that I’ve named sit? We’ve got it mapped out, and we’re revealing the answer slowly, whenever we get a spare moment (because we have day jobs) at Hilobrow.com.

PS: Hilobrow may not actually be a disposition that anyone can actually inhabit; it might be more of an ideal — Highbrow and Lowbrow, reunited and it feels so good — that can only be articulated negatively, by saying what it isn’t. “Let me admit frankly that I have not in my experience encountered any certain specimen of this type; but I do not refuse to admit that as far as I know, every other person may be such a specimen. At the same time I will say that I have searched vainly for years….”

kid bitzer 10.21.09 at 1:23 pm

notice, by the way, how emma’s story of her parents’ striving to like the things you think you ought to like also illustrates some of the underpinnings of the u.s. politicization of “authenticity”.

it’s back to the ‘pissing off the liberals’ thread. while stereotypical liberals are striving to climb up the culture ladder, reactionaries insist that their own love of pork-rinds and hatred of opera makes them genuinely authentic. anti-intellectualism is a virtue, because liberal intellectuals are phonies and hypocrites.

(needless to say, the result of this is that old-money patricians who want to move ahead in the republican party must now take on the entirely phoney and hypocritical pretense that they love pork-rinds and nascar races. and it works!)

perhaps it is also needless to say that the contrast between a newly arrived and ambitious people who are eager to assimilate to the best-connected classes above them by means of education and intellect, versus a resentful underclass that insists on its greater authenticity and rootedness in the cultural soil, has some familiar anti-semitic resonances?

kid bitzer 10.21.09 at 1:27 pm

thanks for showing up, josh.

and may i say–you can disagree with carl wilson all you like, but his lead vocal track on “god only knows” is still sublime.

Josh Glenn 10.21.09 at 1:31 pm

I would have shown up earlier, but I missed this post — John sent me a link, last night.

Josh Glenn 10.21.09 at 1:40 pm

I should mention that I’ve criticized Lynes’ “classic” essay: check it out. This was very early in the Hilobrow.com project, you understand — I should write a new response some time.

Gareth Rees 10.21.09 at 1:58 pm

a ticket to the opera costs less than a seat in the cinema in central London

I’m sure it’s possible to find a pair of tickets satisfying this claim, but to state it baldly like this, as though it were a generalization, seems a bit misleading to me. If I wanted to go out some evening this week, for example, the cheapest remaining ticket to Carmen at the Royal Opera House is £160, whereas the most expensive ticket at the Vue in Leicester Square is £11.90.

Arion 10.21.09 at 2:02 pm

In retrospect, Woolf”s criticism strikes me as enormously parochial. Sure, she was trying to make room for something new, but her assaults on people like Galsworthy and Bennett have a categorical quality that is quite unfair.

Closer to home, a matter of some regret for me is the decline and disappearance of what I call the genteel novel, (using the word in a non-pejorative way). I have in mind the works of Louis Bromfield, John P. Marquand or Edna Ferber, to name a few at random. These were solid craftsman who produced fine novels, for all that Henry James couldn’t stand their like.

I finally decided that the genteel novel had gone out because there weren’t any more genteel readers. In large part the counter culture phenomenon swept away any interest in organized society (and maybe organized society as well). To be sure, places like country clubs still exist, but they have lost their hold on the American imagination. I can’t imagine anyone being culturally ambitious any more. The one exception is the university communities. I’m not sure we’re the worse off for the change. I’m continually astounded and pleased by how deeply cultured are my son and his friends – people in their 40s now.

Ben Alpers 10.21.09 at 2:07 pm

perhaps it is also needless to say that the contrast between a newly arrived and ambitious people who are eager to assimilate to the best-connected classes above them by means of education and intellect, versus a resentful underclass that insists on its greater authenticity and rootedness in the cultural soil, has some familiar anti-semitic resonances?

Now that’s an important gonnegtion!

John Emerson 10.21.09 at 2:53 pm

In retrospect, Woolfâ€s criticism strikes me as enormously parochial.

All of the brow critics strike me as provincial, including Adorno. 50’s America in genral seems distant and strange, even though I was there at the time.

Adono’s culture was deep but narrow. One of the first things I read from that school showed them trying to replicate the life of the German high bourgeois left in Hollywood, supported by people who made soft porn Biblical epics and pop-Freudian Hollywood problem plays with happy endings. It was just too weird.

I have never understood why the varied refugee intelligentsia of ruined Europe received such deference in the U.S. They were smart people, but they were the ones who fucked this up, not us.

alex 10.21.09 at 3:11 pm

Fucked what up? What’s fucked up now that wasn’t already long before Hollywood ate the Frankfurt School?

John Emerson 10.21.09 at 3:16 pm

Fucked up Europe, not Hollywood. The “this” should have been edited out.

ajay 10.21.09 at 3:21 pm

35: OK, should have been “can cost less”.

ajay 10.21.09 at 3:24 pm

I have never understood why the varied refugee intelligentsia of ruined Europe received such deference in the U.S. They were smart people, but they were the ones who fucked this up, not us.

Because Americans knew very well that, unless deferred to, European intelligentsia were quite capable of using their Science Powers to build superweapons that could destroy the world. It wasn’t respect so much as fear.

John Emerson 10.21.09 at 3:43 pm

Everyone should read Eszter’s Dad’s book, “The Martians of Science”. All kinds of interesting stuff about Hungarians, Jews, the beginnings of Big Science, science politics in the 40s and 50s, The Bomb, and so on.

Josh Glenn 10.21.09 at 4:35 pm

It’s bizarre to hear “genteel” used as a compliment, and to see the Frankfurt School and other intellectuals blamed for fucking up prewar European culture! Not sure where to begin with the first, but as for the latter, let’s lay to rest the shibboleth that Adorno hated lowbrow/popular culture. As I’ve repeated too many times, Adorno “enjoyed unique and eccentric lowbrow productions — which he described as being every bit as ’embarrassing’ to the coercive aims of the Disneyfied culture industry as were those highbrow works (e.g., Schoenberg) for which he is a better-known advocate.”

For example: “The misplaced love of the common people for the wrong which is done them … calls for Mickey Rooney in preference to the tragic Garbo, for Donald Duck instead of Betty Boop” (Adorno and Horkheimer, “The Culture Industry: Enlightenment As Mass Deceptionâ€). This is not a rejection of all pop/lowbrow; A&H (primarily Adorno, I think) is here criticizing Disneyfied (low middlebrow) productions. Carl Wilson makes it crystal clear, by the way, that he prefers lowbrow/pop to low-mid like Céline Dion… but he tries — mostly in vain — to force himself to appreciate Dion for (noble, praiseworthy) reasons I’ve analyzed recently at Hilobrow.com.

Josh Glenn 10.21.09 at 4:39 pm

John, what do you think of all this? You didn’t mention what you think of Hilobrow.com’s project when you linked to the site, and though your post doesn’t take sides, it seems more complimentary to Lynes than Woolf. Have my arguments changed your opinion?

John Emerson 10.21.09 at 5:08 pm

Did European intellectuals have nothing to do with the European disaster? Sure, they were on the losing side, most of them, but they had been in positions of influence, and in 1930 or even 1932 many of them were militant and confident of victory. It would seem that events should and some way have diminished our respect for the profound wisdom of Europe, rather than increasing it.

I certainly am not an expert on Adorno, very far from it, but scattered passages have been really horrible. I remember him fulminating about how horrible do-it-yourself hobbyism was and wondering what the fuck he was talking about.

By “John” I presume you mean the real John here, not me.

Josh Glenn 10.21.09 at 5:44 pm

I have DIY hobbies, but am willing to concede that hobbyism is a depressing substitute for the sort of “leisure activity” envisioned by philosophers from Aristotle to Marcuse…

Lee A. Arnold 10.21.09 at 5:53 pm

I don’t think you could write a treatise about class in the United States without mentioning the subtle impact on the WWII generation of the first film version of “The Razor’s Edge” (1946.) If you’ve never seen it, make a date, it’s a terrific and unusual story. I find the director’s hand to be a bit lax but it’s well worth watching, because Clifton Webb is still a revelation (“I do not like the propinquity of the hoi polloi!”) and there have been few beauties to equal that of Gene Tierney. It’s also a Valentine to the destruction of class distinction, and, to a generation coming back from the War, an obvious directive about what they had been fighting for. The most interesting character with regards to the conversation here is Maugham as played by Herbert Marshall (who played the classy jewel thief in Lubitsch’s “Trouble in Paradise” (1932), one of the best romantic sex comedies, pre-Hayes Code, don’t miss that either.) The Maugham character is very low key and at home in both worlds, and some of his voiceovers function as Greek chorus.

For me, what it points to is an evaluation of the 20th-century writers who I guess might have been called “middlebrow” at the time, Maugham, Waugh, Forster, etc, who had the journalist’s dedication to observing the facts and who ended-up creating some of the furthest marks of culture yet. I also think Joyce belongs in there, although he was called a low-brow when he was alive and is now almost unread, being too difficult; and Tolkien, who transferred all his concerns into a complex and thorough allegory and was, I think, dismissed by all but a cult following until the recent movies showed that he easily trumps everybody in the story-structure department.

Story is king.

For class distinction in the U.S.? The 1960’s shook up everything, now the arts have gone into polystylism, the subcultures of youth music and occupational employment determine the dress, and the inundation of world information puts everyone at a conversational disadvantage outside their own specialties and interests — which isn’t balkanizing into new classes so much as atomizing any attempt at valuation. Except every time anew, and from the ground up. Here in L.A. you can show up at a black dress cocktail party in jeans and tennis sneakers and nobody bats an eye. I mean nobody. Mention Welles’ “Chimes at Midnight” (1965), one of the finest movies of all time, virtually an addition to the Shakespeare canon, by one of the greatest directors (who was considered to be a middlebrow at best,) — and nobody’s seen it. I mean nobody. (Get the DVD from Amazon, and never let it go!) Ask about Ozu, Bresson, Fellini, directors who pushed great art in the 20th century as far as anyone, and they may not even have HEARD of the first two. This, is in the filmmaking industry.

John Emerson 10.21.09 at 5:54 pm

My father was a DIY hobbyist, but he also could have been called an amateur scientist or a garage engineer. That kind of thing is continuous with hobbyism. Adorno had the literati’s blind spot to that kind of thing, I think.

nick s 10.21.09 at 6:29 pm

Once established in Australia, though, they made friends in their new milieu, and as a result their house, decorated to their taste, looked odd to them just about every year, for well over a decade.

That’s fascinating, and rings true to a great extent with my expat experience, where the basic premises of how one defines and shapes one’s life and living space are so different.

That kind of mobility also creates opportunities for -brow arbitrage, where someone who imports the cultural trimmings of one milieu into a new one can find that it slots into a very different place on the spectrum. That’s more obvious for less tangible cultural artifacts — hoary but true examples, such as how a British accent perceived as low-brow back home can convey refinement abroad — but it applies to tangible ones as well.

nick s 10.21.09 at 6:29 pm

(Damn you, Markdown.)

John Emerson 10.21.09 at 6:33 pm

There’s a very good Cockney actor in one US city who gets the aristocrat roles.

anon 10.21.09 at 7:27 pm

John Emerson, would you care to elaborate on the role of European intellectuals in the “European disaster”? Sounds like neo-conservative nonsense.

Nick L 10.21.09 at 8:10 pm

If I recall correctly, Adorno was in favour of genuinely nobrow culture, such as juggling or the trapeze. I think that this may have been because they were not pseudo-intellectual attempts at emotional manipulation, but were simply enjoyed for what they were – i.e. exhibitions of skill, craft and ability. The idea of there being something worthwhile or redemptive in purely content free leisure seems to be a common theme in the Frankfurt school, I think that it was Marcuse (or it may have actually been Horkheimer) that found great consolation in watching the animals in the zoo.

Stevie Ray Dedalus 10.21.09 at 9:02 pm

IIRC, Adorno was very proud of a “Last Judgment” he had carved into an apricot pit. He always carried it in his vest pocket and would show it off at the slightest provocation. It was a charming eccentricity until one had already seen it three or four times …

John Emerson 10.21.09 at 9:14 pm

They weren’t guilty. They just failed. In 1930 they were expecting revolution, and by 1934 they were exiles, and absolutely nothing had happened the way they had confidently expected.

Judging by the way the German-speaking world turned out, why should anyone seek German wisdom? It seems to have been a fairly general failure.

John Emerson 10.21.09 at 9:18 pm

Adorno was absolutely horrible on music. At the beginning he accepted Bartok, but when Bartok wrote more accessible pieces during his last couple of decades, he fell from Adorno’s favor , not that he had any reason to care. ( What Adorno said about jazz was famnously awful, of course. )

After about 1870 music tended to be divided between Germanists and anti-Germanists. Adorno was one of the worst of the Germanists., and he tended to ideologize music (and everything) and express his authoritative tastes as though they were authoritative judgments.

Stevie Ray Dedalus 10.21.09 at 9:41 pm

IIRC, Adorno was very proud of a “Last Judgment†he had carved into an apricot pit. He always carried it in his vest pocket and would show it off at the slightest provocation. It was a charming eccentricity until one had already seen it three or four times …

(note to moderator: email address fixed, please delete this note, and previous post)

John Emerson 10.21.09 at 9:45 pm

Anon 53: The neo-cons followed Leo Strauss, one of the people I’m talking about. In 1932 he was a fascist (he said so himself) wondering why the other fascists didn’t like him.

Free market ideology and neoliberalism trace (among others) to Hayek, another Germanic reject. (Mirowski, “Road from Mont Pelerin”.)

Eimear Nà Mhéalóid 10.21.09 at 10:07 pm

I’ve just been rereading Sayers’ Murder Must Advertise which is full of observations on the interaction between class and taste in 1932.

Emma 10.21.09 at 10:29 pm

There are also interesting interactions between class, taste and fashion, and the way that one’s own changes in taste take place subconsciously, so that one can go from thinking something is cool and great, to looking back at one’s earlier self, dressed in flares or dungarees, or eating fried camembert or Bombe Alaska, or finding Monty Python or Frankie Howerd funny, or whatever, and be amazed (and feel a little sick). Something that looked right now looks wrong but only imperceptibly shifts over time.

How does that happen?

It seems to me that much of this is not about conscious, or hypocritical or ph0ny display, but genuine, unconscious changes in structures of feeling that lie much deeper, and yet are so plainly influenced by the people around us.

Emma 10.21.09 at 10:30 pm

Sorry about the two screen names. Your system remembers me differently at home and at work.

anon 10.21.09 at 10:41 pm

“Judging by the way the German-speaking world turned out, why should anyone seek German wisdom?”

Pray tell, what the fuck are you talking about?

I didn’t realize the “From Luther to Hitler” approach to intellectual history had been rehabilitated. Let me get this straight? You trash the rich diverse intellectual product of an entire continent because of one man and one rag-bag ideology? And we’re supposed to take you seriously? Take your consensus history and shove it up your ass.

John Emerson 10.21.09 at 10:52 pm

Are you nuts? Hitler was not “one man”. And note what I said in 55 — I’m not accusing them of being Nazis. They’re not guilty, they just failed — one of the most colossal political failures of all time, and the German intelligentsia had a status in their country that the intellectuals can only dream of. Taking political advice from refugee German intellectuals made as much sense as taking engineering advice from the designers of the Titanic or the Hindenberg.

John Emerson 10.22.09 at 12:07 am

Oh, come on. Someone defend the German intelligentsia.

Moby Hick 10.22.09 at 12:16 am

Uuuh. Max Weber was very smart. He invented …. Protestantism and the kettle grill. And Hegel was totally not a communist. Just cited by The Big Communist. You said that the quiz was going to be multiple choice.

John Holbo 10.22.09 at 12:42 am

Brow arbitrage sounds like a great career choice for a young person. There’s room to move.

Emerson is right about Adorno. His writings about American popular culture are embarrassing. Bringing up Adorno is misleading in these contexts, so I would prefer to leave him out (for the most part), because there are (so far as I can tell) interesting arguments between the high-low coalitionist (from Woolf to Josh Glenn). And it’s also worth listening to the defenders of the middle (from Lynes to Wilson). And of course those who deny the whole framework have a point or two. But if the middlebrows are ever able to set up Adorno, as even approximately representative of the other side, then they get a cheap, one sentence victory: “The problem with what you are saying is that you have no idea what you are talking about.” Adorno was an interesting thinker in a lot of ways, and an elegant writer. I like a lot of his stuff and feel I have gotten something out of it, philosophically. (Yes, me, the anti-Theory guy.) But it is true that no one ever lost an intellectual fight with Donald Duck as badly as Adorno did. (Unless maybe it’s Allan Bloom complaining about Michael Jackson and the Rolling Stones.)

Matt 10.22.09 at 12:49 am

Unless maybe it’s Allan Bloom complaining about Michael Jackson and the Rolling Stones.

Yes, but one things, or at least hopes, that Adorno’s criticism of Donald Duck doesn’t lend itself so obviously to a Freudian explanation as did Bloom’s writings on Mic Jagger.

John Emerson 10.22.09 at 12:55 am

No, no, John, Adorno was just an example. My target was the whole German intelligentsia, 1918-1932. You’re not helping. Your stipend for this week will be withheld.

John Holbo 10.22.09 at 1:13 am

Also, the way I wrote the sentence, it’s worth pointing out that Allan Bloom didn’t actually lose a fight with Donald Duck BY writing about The Rolling Stones. Bloom didn’t have a thing about the Mouse and the Duck, whatever thing he may have had.

John Emerson 10.22.09 at 1:48 am

I feel sorry for those goddamn German intellectualls, with no friends or defenders. Surely they deserve better than this.

herr doktor bimler 10.22.09 at 2:28 am

It strikes me as premature for any intellectual from the English-speaking world to be arguing that “German intellectuals were on the losing side of their cultural civil war against barabarism, so fuck those losers”.

anon 10.22.09 at 2:39 am

You completely dodged my main point. You’re making crazy generalizations about all German (or going by another one of your posts – all European) intellectuals to have ever lived on the basis of political events they exercised no control over. That’s insane.

Incidentally, you get much of your history wrong as well. According to Ian Kershaw, the leading expert on public opinion in the Third Reich and the Nazi leadership, “No Hitler: no SS-police state … no Hitler: no general European war by the late 1930s … No Hitler: no attack on the Soviet Union … No Hitler: no Holocaust.†Hitler, the Germans, and the final solution, 348.

History does not support your view that “Germany†or “Europe†was marching inexorably towards “destruction†because of its rotten culture.

Your entire view of history is premised on the notion that intellectuals are the leading (if not single) force in history and that all outcomes reflect their ideas/behavior. In your view, the rise of Nazism, the fall of France, and the communist takeover in Eastern Europe – all these represent the triumph of rotten ideas. Surely, if European intellectuals had better ideas they would have stopped Nazism and Communism in its tracks. That’s what you’re arguing. But that’s not how things work. History is messy. It’s not collectively willed. There’s structure. There’s politics, economics, anthropology, sociology, etc. and you’re ditching all that for a reductive Geistgeschichte.

You vastly over-estimate the influence of intellectuals on the behavior of everyday people and neglect to mention that intellectuals rarely got involved in politics. Now some historians have argued that this apolitical tendency was a serious shortcoming, but that’s hardly enough to discredit all German culture. Others at the time were similarly apolitical. Romain Rolland and Julien Benda advocated intellectual detachment from politics – as did numerous Anglo-American intellectuals (in fact there is a strong anti-political undercurrent in most Anglo-American political theory which is why we continue to prefer Benda to Nizan).

Finally, you minimize the existence of certain political undercurrents in US history. If Strauss and Hayek are so foreign to American political culture (and so utterly Germanic) why is it that they won such strong followings in this country (and mind you, without concentration camps, superior tank doctrine, or naked occupation)? In trying to excise their influence from American society you indulge in rank gutter nationalism. You don’t like Strauss and Hayek so for you they represent rotten European culture. Instead of examining their place in US history you try to banish them to European history.

You may not like neo-conservative but you do history the neo-conservative way.

John Emerson 10.22.09 at 2:56 am

If Strauss and Hayek are so foreign to American political culture (and so utterly Germanic) why is it that they won such strong followings in this country?

The very question I asked. It strikes me as weird. Both of them were political gurus. Why didn’t anyone ask them about the results they got in their previous job?

I’m sure Kershaw is a fine man but he’s only one guy, and your summary sounds loopy. WHere did he get his Satanic powers? He seems to have stepped into some kind of political cultural vacuum. Where did the vacuum come from, in a country with all those geniuses? There had to be something wrong besides that one guy.

I’m relatively friendly to Great Man theories, but that’s ridiculous.

I’m not a nationalist. I’m just asking why Americans were so worshipful of German imports after WWII.

John Emerson 10.22.09 at 3:01 am

You could add to the list. Heidegger too. Benjamin. Freud and Jung. Wittgenstein.

Emma 10.22.09 at 3:31 am

Damn. I was enjoying this thread till it got jacked. One way or another.

John Holbo 10.22.09 at 5:15 am

I’ll start a fresh thread about brows in a couple days, Emma. I’m feeling an itch in my fingertips, in this regard.

In the meantime: will you gentlemen please discuss BROWS!

bad Jim 10.22.09 at 8:20 am

No, we will discuss Germans and music.

Mozart and Schubert passionately advocated German, or Austrian, music in distinction to the Italian music in vogue at the court. Rossini came along and they sort of enjoyed him. It’s impossible not to. I think even Schumann approved. He liked everything, of course.

The Romantic movement split between the Wagnerians (Liszt, Wagner, Bruckner, Mahler) and the Classicists (Brahms, Clara Schumann and Joseph Joachim, who wrote an opposing manifesto). At this distance it’s difficult to discern the difference. At the same time the Russians were intent on distinguishing themselves from the Germans, and looked askance at Tchaikovsky, whom Brahms eventually took the trouble to visit. In the end the classical canon became rigorously dodecaphonic under the tutelage of Schoenberg, which we forget because everyone was listening to Gershwin and Rodgers and Joplin and Johnson instead.

Mozart, who is mostly middlebrow nowadays, loved bowling and dancing and his viola quintets are still only enjoyed by the cognoscenti.

Urania was once ranked among the muses but the sciences get scant love from the tastemakers now. We can all rank bands and movies and books, but it’s death in polite company to mention hot topics in physics or biology. Most of the people I’ve known would rather discuss ghosts or UFO’s.

herr doktor bimler 10.22.09 at 9:00 am

Is it high- or low-brow to point out that Austrians (Freud, Hayek, Wittgenstein) are not the same as Germans?

John Emerson 10.22.09 at 11:32 am

“German-speaking world”. I should have thrown in Hesse.

John Emerson 10.22.09 at 11:42 am

Brow:

http://arts.anu.edu.au/sss/pols3017/Images/Theorists/hayek.jpg

The Russian musicians of 1880, except for Czajkowski, were mostly either anti-Germans or Germans. The Germans were mostly Jews, which makes the question a bit tricky. French musicians became anti-German a little later (Satie, Debussy, Ravel.) Stravinsky had no principles and didn’t care, but was musically closer to the anti-Germans. Bartok was an anti-German, and probably Janacek.

Walt 10.22.09 at 12:07 pm

I was once at a party at a frat where around 3am I held an entire staircase of fraternity brothers riveted by answering their questions about quantum mechanics and black holes. It was very unexpected.

Josh Glenn 10.22.09 at 12:34 pm

I don’t think Adorno lost the argument with Donald Duck. He regarded Disney as a factory for cranking out sameness, but enjoyed Fleischer’s Betty Boop. From our vantage point, we can see that early Disney stuff was great compared to cartoons that came later, but to Adorno, Disney cartoons were cute, Fleischer’s were sophisticated; the former were goofy, the latter surrealistic, darkly humorous; the former were childish, the latter included adult psychological elements and sexuality. Disney’s success more or less drove Fleischer out of business; Adorno feared that American culture was becoming “Disneyfied” (surely not a term that anyone here uses in a positive sense?). These are the same concerns at the heart of Kim Deitch’s terrific graphic novel The Boulevard of Broken Dreams, right? So why do well-meaning intellectuals crap on Adorno? As Nick L points out, Adorno was not anti-lowbrow. He was opposed to low-middlebrow, which was replacing lowbrow!

John Emerson 10.22.09 at 12:51 pm

Well, I’m not generally regarded as well-meaning. And I think that brow theory, like Generation x,y,z…. theory, is a crock. And that fifties culture criticism is quaint and silly.

I can sympathize with Adorno in the context of his personal tragedy, and perhaps admire some of his writing, but I don’t think that he ever should have been thought of as a source of wisdom, guidance, or insight.

Adorno was big with the New York Intellectuals and the “consensus theory” political ideologues. The NYI, per wiki, were Philip Rahv, William Phillips, Mary McCarthy, Dwight Macdonald, Hannah Arendt, Delmore Schwartz, William Barrett, Lionel Trilling, Diana Trilling, Clement Greenberg, Harold Rosenberg, Richard Hofstadter, Harvey Swados, Richard Chase, Saul Bellow, Isaac Rosenfeld, Sidney Hook, Irving Howe, Alfred Kazin, Robert Warshow, Daniel Bell, Irving Kristol, Nathan Glazer, Norman Podhoretz, Susan Sontag, Marshall Berman, and Michael Walzer.

Isn’t that a dated, provincial group? Kristol and Podhoretz and the neocon aftermath aside, how many of them deserve reading any more, except by Americanists? I’d say Arendt and Berman. Most would add Bellow and maybe Sontag and Bell. I read Hofstadter because of his maleficient influence.

Brow theory is a nightmare from which we are trying to awake.

Walt 10.22.09 at 1:07 pm

Mary McCarthy’s Groves of Academe should be more widely read than it is.

John Holbo 10.22.09 at 1:23 pm

I don’t have my Adorno handy, to settle the question – or at least to make clear to everyone what is being argued about. If someone has the stuff about Mickey and Donald and jazz and all the rest handy, and cares to type in a few representative passages, that would be welcome. But in the meantime: Deitch’s indictment of Disneyfication seems to me subtle and perceptive and appreciative in its comic despair … I could go on. Adorno seems to me crude and one-note. Which, coming from Adorno of all writers, is a disaster. One-note Hegelianism is the worst music in the world. Adorno sees American popular culture through the lens of his late nightmare experience in Europe, for which we can forgive him; but he’s just slapping on a template that doesn’t fit. The badness he saw (if we grant that much of it was actually bad) was not quite like the badness he had escaped. Greenberg and MacDonald seem to me comically extreme in their negativity, at times, but they have at least one avenue of actual contact with what they are discussing. They are natives. Adorno loathes some of this stuff so deeply that he can’t bring himself to wallow in it to the degree a critic must, especially a foreign critic.

But obviously some Americans have read Adorno and think otherwise. And, hell, it’s probably been 10 years since I read those bits about the mouse and the duck. I prefer his stuff about Hegel. Quote away and shame me with the plausibility of the anti-Disney stuff. (It’s not that I’m unwilling to think well of Adorno.)

John Emerson 10.22.09 at 1:40 pm

I read McCarthy’s Groves as Americana, and it was fun.

Adorno’s Hegelianism was one of the things that repelled me. Every analysis of anything was world-historical, and always a decisive judgment.

I’dm willing to say that that X means the end of civilization as we wished we knew it, for many values of X, but I’m a troll and a comnedian. When Adorno said something like that, for example about jazz, he meant it.

My knowledge of Adorno is strictly on the rotten eg principle. I’ve thrown his books across the room cursing 5 or 10 times.

John Emerson 10.22.09 at 2:05 pm

Part of my dislike of Adorno is that he and his co-authors on “The Authoritarian Personality” convinced Hofstadter that Hitler was a populist and that the Populists were proto-Nazis.

As late as 1983 (Webster’s New International) “Populist” was defined as a proper noun, designating the American Populists and the not-very-similar Russian Narodniks. But starting with Hofstadter (I think) the common noun “populist” has had increasing currency, with the meaning “Hitler, the Populists, etc.” This has not been a good development.

Platonist 10.22.09 at 3:18 pm

Josh Glenn @81:

“So why do well-meaning intellectuals crap on Adorno? As Nick L points out, Adorno was not anti-lowbrow. He was opposed to low-middlebrow, which was replacing lowbrow!”

Haven’t you answered your own question? Today’s well-meaning intellectuals crap on Adorno because he is opposed to _them_ (though I’d include medium and upper-middlebrow to his opponents). They crap on Adorno because he has the gall to criticize jazz and cartoons, and all awesome high/low-bridging contemporary intellectuals love such things. The Middlebrows won the culture wars (the last 10 years of history not withstanding, since this is a function of middlebrows manipulating the lower to their ends), so their greatest enemies are doomed to an ironically cartoonish (Daffyesque), ironically simplistic (Emersonian) wholesale dismissal.

@84

“Adorno seems to me crude and one-note. ”

This is an appropriately middle-brow way to evaluate a judgement about how and why the world has gone to hell in an unnecessarily tasteful handbasket. Needs more notes! My kid could paint that! You call that a beer?

#86

“My knowledge of Adorno is strictly on the rotten eg principle. I’ve thrown his books across the room cursing 5 or 10 times.”

This is telling — I rarely find myself throwing books unless they’ve landed a punch.

Chris 10.22.09 at 3:18 pm

If that’s the same Hofstadter who wrote “The Paranoid Style”, I don’t think his influence was wholly maleficient, even if he confused the paranoid style with populism.

It seems to me that “populism” is a term so debased today that it basically means “anyone who claims that the lurkers support them in e-mail”, which generally does include authoritarians, the paranoid style, and proto-fascists, but isn’t limited to them. The first meaning listed in my modern dictionary for “populist” is “a member of a political party claiming to represent the common people”, so that while the Populists were certainly populists, they weren’t the only populists and people with quite different views can be populists as long as they *claim* to represent the common people.

That dictionary was written after the meaning shift you deplore, but I’m not sure that Hofstadter deserves the chief blame, or even any blame, for the meaning shift.

John Emerson 10.22.09 at 3:38 pm

Yeah, jazz is middlebrow. Gotcha.

We disagree about Hofstadter and populism. I’ve dealt with this at length at Open Left, where one guy disagreed vehemently. When Hofstadter wrote about the Populists and Progressives (The Age of Reform more thean the Paranoid / Anti-Intellectualism books) the Populists were respected and the word was a proper noun. He was the revisionist, and via Gellner’s anthology, went into the European and more general historical discourse.

But he misrepresented the Populists. So now we have a generalized definition that doesn’t really attach to its namesake, though most educated people think it does.

Hofstadter’s books were literary-historical political polemics (historians doubted his research, which was all secondary) based on the contemporary context: Joe McCarthy, on the one hand, and the takeover of the Democratic Party by intellectuals, eperts, and administrators, which Hofstadter pretty explicitly advocated. (He openely dreamed of a Democratic Party on the British Conesrvative model).

It was double edged. He convinced the Democrats to minimize popular appeals, and he validated demagogues who could take the name of a respected historical poetry (which David Duke actually did).

Hofstadter did Hitler and McCarthy no harm by calling them populists. He only harmed the memory of the Populists.

And now we have the biggest financial crash since the Depression, and the Democrats aren nobly refusing to capoitalize on it, because that would be a populist and Nazi thing to do.

John Emerson 10.22.09 at 3:40 pm

My fingers wanted “poetry” instead of “party”. They have their own mind.

Platonist 10.22.09 at 4:06 pm

“Yeah, jazz is middlebrow. Gotcha.”

No, it’s just that middlebrows like it, and in the wrong way.

Jazz is lowbrow. It’s the middlebrows who took it over and declared it highbrow. Now it’s “America’s classical music.” (Ken Burns’ hairline makes it hard to tell where his brow is, but I don’t think it’s very hard to guess…)

“I’dm willing to say that that X means the end of civilization as we wished we knew it, for many values of X, but I’m a troll and a comnedian. When Adorno said something like that, for example about jazz, he meant it.”

It’s true that he meant it, but is it so self-evident that he was wrong? I’ve always suspected that we’ve been living post-civilization for at least 30 years. (Not necessarily with a bang but a whimper, etc.) I say that as a troll, a comedian, and in earnest.

bianca steele 10.22.09 at 4:07 pm

p. 209: “The shrew, a fossilized survival of the bourgeois esteem of women, is invading society today. With her endless nagging she takes revenge in her own home for the misery inflicted upon her sex from time immemorial.”

p. 158: “One simply ‘has to’ have seen Mrs. Miniver, just as one ‘has to’ subscribe to Life and Time.” One can easily imagine Herr Adorno writing this down after a cocktail party that had been especially unpleasant for him, at which some faculty wife recommended the film to him in terms he manifestly misunderstood, a misunderstanding that taints everything else he wrote.

p. 165: Calling co-workers by their first names (or perhaps their nicknames: “Bob” and “Harry”) “reduces relationships between human beings to the good fellowship of the sporting community and is a defense against the true kind of relationship.” This is even sillier than Anthony Burgess complaining about saying “Dickinson” because poet or not, calling by surnames is a male school habit and inappropriate for others.

There is a passage somewhere where he criticizes the kind of upper middle class housewives Friedan wrote about, by saying how horrible it is that their husbands permit them to have cultural interests.

John Emerson 10.22.09 at 4:22 pm

209/158: Like I said, Charlotte Haze. The US was engaged in a nationwide social-climbing effort during the fifties. Nabokov is quite amusing on American kitsch. (As I’ve mentioned here recently, Kerouac’s “On the Road” came out a little after Nabokov’s road novel “Lolita”, but they were written at roughly the same time about events that occured in the forties sometime, and both included trips through Colorado as I recall. Nabokov and Kerouac themselves conceivably might have met in Colorado during the 40s, though I haven’t traced that down to exact dates and places.

The culture wars can be traced back to the U-non-U-brow debate, where Americans often adopted Continental or British values, and further back to Mencken, TheSmart Set, the WWI New Republic, etc.

Ben Alpers 10.22.09 at 5:42 pm

John Emerson @ 83: Two cheers (at least) for the New York Intellectuals. Though I’m an Americanist (and thus my view may provisionally not count), I certainly think that Dwight Macdonald and (the early) Sidney Hook are still worth reading.

And Hofstadter is one of, if not the, greatest historians of his generation. Yes, he was wrong about Populism. And Emerson is right to see Hofstadter’s anti-P0pulism (and more general anti-popularism) as part of a larger, unfortunate tendency of postwar American liberalism. Still, like all Hofstadter’s work, The Age of Reform is worth (re)reading. For all its mistakes, big and small, it’s still brilliant and complicated. It rewards attention.

It’s also worth pointing out that Lawrence Goodwyn, whose work on Populism was an entirely necessary corrective to Hofstadter’s, significantly overcorrected for Hofstadter’s mistakes. Democratic Promise / The Populist Moment (the latter is the abridged version of the former) is also still worth reading, too. But it’s a less nuanced work than The Age of Reform. And its heroic portrait of Populism is also not quite right about the movement (Goodwyn’s vilification of fusionism and the Bryan presidential campaign seems particularly dated….and I say that as a sometime Third Party activist!).

At the risk of sounding Hegelian in this thread, out of Hofstadter’s thesis and Goodwyn’s antithesis has come a raft of more complicated synthetic work on Populism that takes better measure of both its positive and negative qualities (and understands it as a more local phenomenon both spatially and temporally, too).

Ben Alpers 10.22.09 at 5:43 pm

Correction: “Yes, he was wrong about Populism. And Emerson is right to see Hofstadter’s anti-P0pulism (and more general

anti-popularismanti-populism)…”Martin James 10.22.09 at 5:48 pm

Being thoroughly lower middle brow myself, of course I think Godwin’s law was invented by the upper middle-brower’s to distract people from the open realization that there is no highbrow and even if highbrow was not extinct it would be short solace in the face of lower brow’s with a keen eye for banners, badges and uniforms.

Highbrow is dead, Mencken is God and yes, everything is permitted, especially greed, poor grammat and typos.

John Emerson 10.22.09 at 6:01 pm

But Mencken was a gold-bug Cleveland Democrat, a Roosevelt-hater, and sqishy on Hitler! I’m niot saying you’re a Nazi though.

AT the present conjuncture, Ben, Hofstadter is Satan. For that reason I’ve read most of his books, sequeing into most of Lasch’s books.

Platonist 10.22.09 at 6:09 pm

@93 reminds me of American and Christian jingoists self-righteously quoting gotcha snippets of the Koran. Good show.

Ben Alpers 10.22.09 at 6:19 pm

AT the present conjuncture, Ben, Hofstadter is Satan. For that reason I’ve read most of his books, sequeing into most of Lasch’s books.

I think you’re giving Hofstadter too much credit for creating an unfortunate political tendency of which he was an important example (since I so rarely get a change to plug it, see my book for much, much more on the origins of the rather cramped postwar liberal vision of democracy).

Besides, as all Upper Middlebrows know, Satan gets all the good lines!

bianca steele 10.22.09 at 6:23 pm

@99: Maybe someone who likes Adorno better than I do could do an impression of said person quoting gotcha snippets from the Bible.

Platonist 10.22.09 at 6:24 pm

“Besides, as all Upper Middlebrows know, Satan gets all the good lines!”

This could be a fun game: “Upper, Middle or Low-Brow?”

Satan: upper

Man: middle

God: low

Platonist 10.22.09 at 6:26 pm

Or:

George: upper

John: middle

Ringo: low

Paul: lower than low

John Emerson 10.22.09 at 6:39 pm

I think you’re giving Hofstadter too much credit for creating an unfortunate political tendency of which he was an important example.

Perhaps. But you have to personalize your enemy. Hitler taught me that.

I’ll get your book. From my reading, by 1938 everyone was calling everyone else either a fascist or a communist. Sen. Lundeen of MN was called a Communist in 1924 or so, and a Nazi in 1940. One of the people who called him a Communist was later convicted of being a Nazi agent.

Walt 10.22.09 at 8:10 pm

Platonist, your analysis is wrong in every particular. Middlebrow was completely exterminated by the highbrow/lowbrow alliance that is already in view in Woolf’s time. Woolf liked the highbrow because it was sophisticated, and respected the lowbrow because it was authentic. Middlebrow’s great crime was aspirational intellectualism, which made it neither sophisticated nor authentic. The reason why the Hefner quote — “We enjoy mixing up cocktails and an hors d’oeuvre or two, putting a little mood music on the phonograph and inviting in a female for a quiet discussion on Picasso, Nietzsche, jazz, sex.†— sound so ridiculous to modern ears is that aspirational intellectualism is the worst possible fault. Where in the 50s we had Playboy, now we have Girls Gone Wild. In the wake of the 60s, authenticity became the great highbrow virtue, so highbrows now perform highbrow-ness by miming authenticity.

Maybe Ken Burns is plausibly middlebrow, but the list of other candidates is pretty short. Jazz has like 7 living fans left in the world, so it’s not much to build a case on.

Chris 10.22.09 at 8:29 pm

Personally, I think my biggest beefs with small-p populism are its tendency to engage in moral panics, refusal to acknowledge nuance/complexity and hostility to people who point it out, and attempts to tear down the prestige of intellectuals and professionals and replace them with “gut checks”. (These obviously go together quite a bit.)

Were those not characteristics of capital-P Populism?

John Emerson 10.22.09 at 8:51 pm

Anti-intellectualism wasn’t really a factor for the Populists. They were greenbackers and or free silver inflationists, and they had their own intellectuals against the gold bugs. They were more right than wrong. Their enemies were the monopolies and the banks, especially the national and British banks (who did control world credit). Destler’s bio of Demarast Lloyd or Woodward’s bio of Tom Watson describe Populist intellectuals.

The enemies of the Populists were not the intelligentsia, but finance, big business, and the corrupt party machines (Roscoe Conkling, Boss Tweed, and dozens of others).

The Populists were moralistic and used overheated rhetoric the same as the Democrats and Republicans of the era.

As for nuance and complexity, I think if the Democrats dialed their nuance buttons down a few notches that would be a wonderful thing. In order to take any initiative of any substance, at some point you have to stop saying “on the one hand… but on the other hand…..”

The main reason for Democratic lack of spine is corruption, but there’s a philosophical aversion to having any definite opinions about anything among what I’ve called the party’s wonk demographic — well educated Democrats who constitute a big chunk of the rank and file, but who think that they’re policy experts and deep strategists, and who ntry to figure out the outcomes of fights before they’re fought. The net outcome in game theory terms is premature compromise settling for the sure thing rather than fighting for the best outcome.

So perhaps we just disagree. It’s too late to do the right thing about the financial meltdown, for example, but some populist anger might have made it possible to do so. Instead, we stuck with our same old “shit happens, objective forces, nuances and complexity” reaction and decided that we should settle for a quick fix and reward the malefactors and incompetents.

And essentially, that was because “we” do not really have a representative in the game. It’s just the finance A Team fighting the Finance B Team, just as it was in Grover Cleveland’s day.

Keir 10.23.09 at 1:21 am

Isn’t that a dated, provincial group? Kristol and Podhoretz and the neocon aftermath aside, how many of them deserve reading any more, except by Americanists? I’d say Arendt and Berman. Most would add Bellow and maybe Sontag and Bell. I read Hofstadter because of his maleficient influence.

And Rosenberg and Greenberg, and Dwight Macdonald. And at that point, five out of so many is actually pretty good.

John Emerson 10.23.09 at 2:06 am

You’re at the far end of the range.

Another way to state the question: are there any must-reads in the group? Any who will be read in fifty years? I’d say two at most, and Arendt is from Elsewhere.

Keir 10.23.09 at 2:31 am

Greenberg will be read in fifty years time no worries. Sontag probably also, as will Arendt and Berman.

I also think it’s a bit of a dodgy way of arguing, this idea that somehow we should rate intellectuals based on political achievement; it’s a rather Socialist Realist way of thinking, and I do not think it will prove practically productive.

(I am also generally suspicious of anti-European-thinking arguments, on account of the whole nasty ick thing they have going on. And you confuse communists with liberals in a rather annoying way.)

John Emerson 10.23.09 at 11:06 am

Just look globally at Europe, 1914-1945. In 1913 Europe wis out question the culmination of human civilization. In 1946 it was a heap of rubble and tens of millions of premature cadavers. You’d just have to say there was some terrible flaw there.

And a lot of Europeans did, after WWI, but then they came up with solutions worse than the problem.

Neither Communists nor fascists had a role in making WWI happen. (The causality was the other way). It was all done by orthodox, mainstream, stodgy, right-thinking people.

This related to the brow controversy, because a lot of the brow thinkers were worshipful of European culture and contemptuous of American culture., and the whole episode was collective social climbing. It just strikes me as an odd episode.

Fortunately for my opponents, the US has now achieved European levels of culture and military organization.

Chris 10.23.09 at 1:59 pm

The net outcome in game theory terms is premature compromise settling for the sure thing rather than fighting for the best outcome.

What’s premature about that? Settling for the sure thing beats the hell out of fighting for the best outcome, losing, and getting nothing. That’s the reason compromise was invented. Fighting isn’t a virtue. It’s a tactic, and not always the best one. Assuming that you’re going to win all your fights is a very old, very popular, very stupid idea.

Yes, there will always be people who think that more could have been achieved, but without inter-universal travel, you can’t tell if those Monday morning quarterbacks are right or not. History is littered with political Icaruses, so I find the desire to fly lower completely understandable and rational.

The current example is health care, a tremendously contentious issue on which making even tiny gains requires massive effort against some of the most powerful entrenched interests in the country and the sweeping ambitions of the Clintons achieved nothing (or possibly contributed to the Republican takeover of congress that eventually led to Clinton’s impeachment).

I guarantee you the proposals advanced by wonks when you have to include Joe Lieberman, Ben Nelson, and Mary Landrieu to get a bill to a vote will look rather different than the proposals they would advance if those people were irrelevant. Why shouldn’t they be? An ambition to do the impossible is useless. That’s why it’s important to know what’s possible and what isn’t.

I suppose this just confirms that I’m one of those unambitious wonks who’s willing to accept the insurance companies continuing to make money if it will let us save a measly few thousand lives.

John Emerson 10.23.09 at 3:20 pm

Gotcha: you’re the one who wants to save lives, where I’m a purist and don’t care about human suffering. You looked over all human history and know the truth: the only lesson is compromise. Thank you for playing true to type. If I could, I’d pickle you and put you in my loser Democrats museum, compromise monomaniac division.

Settling for the sure thing beats the hell out of fighting for the best outcome, losing, and getting nothing.

It doesn’t in the long run, though. If the other side knows you’ll never fight, they’ll low-ball you. That’s what the Republicans did during the very successful (by their standards) Bush years. In a a bluffing game, you have to bluff or you lose a lot, though if you do bluff, you lose a few. (This is the third paradox of rationality in Nigel Howard’s “Paradoxes of Rationality”, BTW. No risk, no gain. That’s why I mentioned game theory. And that’s why I talk about “figuring out the final score before the game is played”. )

The main problem with the Democrats is corruption, but playing their hand weakly, which they always do, makes things worse. But rank-and-file purist resistance has already improved on the wretched Baucus bill and it seems possible to improve it even more.

Thank you for being true to type.

Harold 10.23.09 at 5:38 pm