Haven’t seen the new one yet (it will be the four year old’s first movie in the theatre, so we are trying to figure out a family expedition, so that everyone can enjoy him enjoying it), but its arrival reminds me that I’ve been meaning for ages to post on how _Toy Story 2_ maps out the major themes of Ishiguro’s _Never Let Me Go._ They both are driven by the same basic idea – of highly intelligent, potentially autonomous creatures who define their happiness entirely in terms of the happiness of others. In _Never Let Me Go_, this makes the (liberal) reader quite queasy. In _Toy Story 2_, this is treated as an entirely happy and natural state of affairs. Perhaps it shouldn’t be – and that so many people take the social relations in _Toy Story 2_ for granted, suggests that NLMG‘s clones’ acceptance of (and even joy in) their status is less socially unrealistic than some of its critics think.

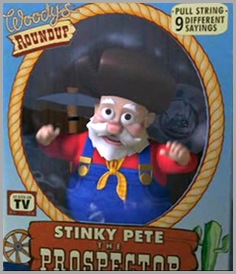

There’s an article to be written on this (perhaps taking Gene Wolfe’s chilly little short story, “The War Beneath the Tree”:http://books.google.com/books?id=N-IemS8Uqn0C&pg=PA189&lpg=PA189&dq=%22war,+beneath+the+tree%22&source=bl&ots=d01op1lBBu&sig=3z2oDPQu93QmvgwOGa4MP7GKELQ&hl=en&ei=NLgeTLGDMYK0lQf96Nn9DA&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=4&ved=0CB4Q6AEwAw#v=onepage&q=%22war%2C%20beneath%20the%20tree%22&f=false in along the way. In the meantime, from this perspective, Stinky Pete is perhaps the only character in _Toy Story 2_ who is genuinely free, even if he _is_ stuck in a box for most of the movie.

Update: “Tom Houseman”:http://www.overthinkingit.com/2010/06/18/toy-story-proletariat/# has similar thoughts.

{ 45 comments }

Elf M. Sternberg 06.21.10 at 1:54 am

Oh, there’s a lot to be written about the whole issue of toys and “ownership.” On the other hand, the characters in Ishiguro’s story are human beings– I never did suspend my sense of disbelief reading it– but the real point of TS2 is that they are toys. Absent some arbitrarily chosen transcendent “purpose,” our purpose is pretty much nil: we are what we are, highly evolved reproducers with a lot of excess historical baggage.

The characters in the TS universe aren’t human beings; they don’t have reproductive drives. To call Pete an “existential hero” is to make a category error– to identify too closely with Pete. It’s the same error Spielberg tried, but failed, to get his audience to understand in AI, and it’s the same error Brian Aldis did not make in the basis for Spielberg’s film, “Super Toys Last All Summer Long“.

If we ever do actually make artificially intelligent machines, and if they don’t wipe us out in some arbitrary and accidental resource race, they will probably look upon the Toy Story series as a bizarre allegory of their own existences.

nnyhav 06.21.10 at 2:17 am

May I recommend Milliways?

mo 06.21.10 at 2:50 am

Wonderful post. I was disturbed by the toys’ self-effacing love in Toy Story 2!

But they aren’t blindly loyal. There’s that scary kid who mutilates them. They hate him.

P.D. 06.21.10 at 3:32 am

Elf is entirely wrong here. Our lives do mean a great deal – not because of some transcendent purpose, but because of human projects and values. That’s the whole take home lesson of existentialism.

Many human projects have nothing to do with reproduction, but they are important because they are human projects. So the fact that the toys can’t reproduce is irrelevant. The real question is whether they can set ends, pursue projects, and become sources of meaning.

That is partly a metaphysical question about what their world is like. Are they in bad faith? or do their lives have a transcendent meaning that real lives don’t have?

Elf M. Sternberg 06.21.10 at 3:40 am

Well, if we’re going to argue from that branch of philosophy, then Stinky Pete is indeed cast into the role of the villain anyway. He has rejected his transcendent purpose.

The transcendent purpose is made explicit twice in the third film, only one of which I can describe without a spoiler: suffice it to say that of all the characters in the film, Woody suffers the least because he never loses faith in his owner’s love for him. Existential threats are very real in the third film, but the horror of that threat to the rest of the gang is only effective after the rest of the gang come around and regain their faith.

As your bog-standard philosophical naturalist, I may find fellow-feeling in projects that seem to have nothing to do with reproductive success, but can never quite escape from trying to analyze our activities from a Darwinian point of view.

john c. halasz 06.21.10 at 4:00 am

Robert Walser.

LFC 06.21.10 at 4:48 am

Elf M. Sternberg:

What about the undeniable fact that there are humans who choose not to reproduce, and why, btw, use the Freudian language of drives in an ostensibly Darwinian context? I find the statement “The characters in the TS universe aren’t human beings; they don’t have reproductive drives” to be both repellent and inaccurate in its view of humans (or to put it in other words, normatively flawed and empirically wrong).

rm 06.21.10 at 5:50 am

I reject Elf’s Darwinian reductionism, but I still think it matters that the toys in Toy Story are toys, and the clones in Never Let Me Go are human beings. Stinky Pete wants to be embalmed forever in a museum — I think he himself does not know how bad that will be for him, because he is psychologically damaged by his upbringing as a collector’s item. I love the way the Toy Story plots are motivated by the passions of the characters (especially the first movie); their passions and anxieties drive them, but are not quite the same as human passions. They have a convincing toy psychology.

In Never Let Me Go the society has decided, from the moment cloning began in the 1950s, that clones are disgusting, unspeakable objects, even though they are obviously human and the society makes many pragmatic accomodations for their humanity. This makes the reader imagine what it was like to live the contradictions of slaveowing, or of consigning mentally ill or disabled people to lifelong prison. More uncomfortably, it makes the reader wonder who we are treating this way today. Toy Story doesn’t really have these contradictions.

So, I think Stinky Pete is much more like Ishiguro’s clones than are Woody, Buzz, and the gang. Pete, like the clones, has decided not to think about the damage he incurs from living the purpose he’s been chosen for by others. It’s Woody who imagines the Sisyphus Action Figure happy and sets about living a meaningful life.

Can’t wait to see the third movie.

dsquared 06.21.10 at 6:10 am

why, btw, use the Freudian language of drives in an ostensibly Darwinian context?

nothing wrong with this – it’s often worth reminding evolutionary psychology types that the ‘discovery’ that the major drives are basically evolved behaviours is already there in Freud.

Neil 06.21.10 at 7:32 am

Most bog-standard philosophical naturalists reject Elf’s ‘bog standard philosophical naturalism’. I can think of one philosopher on his side (Rosenberg); the ones against include such alleged reductionists as the Churchlands.

Doug 06.21.10 at 8:03 am

nnyhav @2, Henry has only done five impossible things before breakfast, and thus is not ready yet.

Ed 06.21.10 at 1:26 pm

You may want to check out the discussion of the same exact topic here: http://www.overthinkingit.com/2010/06/18/toy-story-proletariat/.

Henry 06.21.10 at 2:04 pm

bq. Well, if we’re going to argue from that branch of philosophy, then Stinky Pete is indeed cast into the role of the villain anyway. He has rejected his transcendent purpose.

Well if we _really_ want to go that route, then very clearly Stinky Pete is the Miltonic Satan of the _Toy Story_ saga. Better to reign in a Japanese toy museum than &c&c.

Doug – I think I _have_ accomplished six impossible things before breakfast. I’ve also succeeded in producing an immanent-moral-order-in-fiction defense from a guy who got a cease-and-desist letter from Larry Niven for “writing male-Kzin-on-male-Kzin BDSM fantasies”:http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elf_Sternberg ;) Which last achievement btw I am prepared to admire deeply from a distance. Kzin-Kzin bondage is not my thing – but it is a very plausible corollary of a profoundly misogynistic society (females aren’t intelligent – way to go Larry!) based entirely around male codes of honour and harsh prestige rankings. That Larry Niven can’t stomach this even as a possibility may possibly say something about Larry Niven.

The Modesto Kid 06.21.10 at 2:35 pm

Thanks for that link, Ed — a really interesting post. I skipped Toy Story 2 (I seem to remember really disliking the first movie but cannot remember on what grounds…) but this post and the Overthinking It piece are making me want to catch 3.

Will 06.21.10 at 3:00 pm

Thank you for the link to the Gene Wolfe story, by the way. I have read almost all of his novels and a number of short stories, but I wasn’t familiar with this one.

It seems strange to suggest that the fact that the characters in TS are toys makes it alright that they have this self-effacing devotion. These characters are clearly not toys in the regular way we understand toys. They are not inanimate objects, but are actually intelligent beings. It seems repugnant that sophisticated, intelligent, and sentient (in the literal sense – they feel pain) beings have been duped into this kind of blind devotion to another person. I think the slavery analogy is somewhat apt, but maybe this is a better metaphor for a cult, at least insofar as the effect it has on the characters.

norbizness 06.21.10 at 3:19 pm

Jingle Billy: Okay! Nap-time! (shotgun blast)

Meatwad: Jiggle-Billy!!

Happy-Time Harry: I had nothin’ to do with it man. He did it himself. Because he couldn’t stand being with you!

Meatwad: Oh, you see this? Look he’s still jigglin’.

Happy-Time Harry: No, that’s something else.

Jingle-Billy Head: Hey partners, I’m still alive! I’m just real depressed…

chris 06.21.10 at 3:22 pm

So basically you’re saying that most of the toys have a creepy slave mentality, like they think they’re some kind of property?

…Oh wait.

I think this just goes to show that sentience matters; if toys really did have minds of their own we’d have to totally change the way we interacted with them, because treating them as property *would* be slavery. (As it would be for sentient robots, uplifted animals, etc.)

On the other hand, if they really do have a kind of permanent Stockholm Syndrome… our existing systems of morality are designed for human-human interactions, not for human-something else interactions. Maybe the rules governing slavery *wouldn’t* apply to toys because their minds are so different, and it’s really only immoral to keep a sentient being as a slave if it wants to be free. (Cf. consensual “slavery” — albeit not legally enforced as such — that some people practice in their intimate relationships.)

But as long as the toys conspire to conceal the fact that they have minds of their own, it seems somewhat unfair to think that the humans should accord them the rights that go with that status.

ajay 06.21.10 at 4:21 pm

highly intelligent, potentially autonomous creatures who define their happiness entirely in terms of the happiness of others.

Does it make any difference that the toys actually know this is the only reason they exist? They aren’t troubled by the Big Question of the Meaning of Existence. They know the meaning of their existence. Just as a devout Christian would believe that Man’s chief end is to glorify God, the toys believe that their chief end is to make kids happy. And they’re right. They are, after all, toys. That’s what they’re for.

But as long as the toys conspire to conceal the fact that they have minds of their own, it seems somewhat unfair to think that the humans should accord them the rights that go with that status.

Back to Niven, who argued that it’s OK to experiment on dolphins even though we suspect they might be sentient, because, after all, this will give them a great motive to prove their sentience to us…

roac 06.21.10 at 4:33 pm

Somebody has to say it: The suggestion in the Overthinking post that the TS movies are intended to induce a slave mentality in children crosses the line into paranoia. (Our masters, by and large, prefer to distract attention from their existence. It seems to be working.)

The movies are about toys because when the first one was made, it was possible to render manufactured objects convincingly on a computer, but not humans or animals.

And speaking of animals, this discussion seems incomplete without some attention to the various relationships between humans and animals, which has been the subject of lots of movies. For instance, one alternative to the TS movies would be a Chicken Run about toys. (The alternative in which the toys rise up against their masters has already been done, but the audience is different.)

Keith 06.21.10 at 5:35 pm

What I find most fascinating is that Stinky Pete is clearly capable of leaving the box he’s in but only does so when forced to confront an externally generated out-of-context threat. For him, thinking and acting outside of the box entails an actual box that otherwise limits his interactions with others on both a social and emotional level. He has to physically leave his comfort zone and put himself in dangerous situations that could not only cause him harm but alter his status (mint in the box). As such, he’s the most status-conscious of the toys, even more so than Rex, who not only knows his own personal history but is acutely aware of his lineage (remember, he knows that his line of toys was purchased through a leverage buyout of a smaller company by Mattel).

There’s a whole thesis right there: Stinky Pete vs. Rex as emblems of status and hierarchy in a materialist society.

chris 06.21.10 at 5:35 pm

Just as a devout Christian would believe that Man’s chief end is to glorify God, the toys believe that their chief end is to make kids happy. And they’re right. They are, after all, toys. That’s what they’re for.

Hold on a minute — that was the humans’ goal in creating the toys, but why should that necessarily be the toys’ own goal? Isn’t their willingness to adopt someone else’s purpose for them just further evidence of their slave mentality? The right to set and pursue their own agenda is fundamental to existence as free sentients, isn’t it? (And has someone already made the analogous criticism of _The Purpose-Driven Life_?)

Keith 06.21.10 at 5:44 pm

rm@8: I still think it matters that the toys in Toy Story are toys, and the clones in Never Let Me Go are human beings.

There’s no categorical difference. Both are manufactured lifeforms with agency. That agency is restricted or enhanced, depending on social forces prevalent in their unique societies. Both the clones and the toys are capable of breaking social barriers (acting as self-motivated agents in front of humans) but choose not to do so with rare exceptions.

Interestingly, the Andys/ Replicants from Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?/ Blade Runner are in a similar position but are active transgressors of the restrictive social barriers, a action that follows to it’s logical extreme in a human-centric society. If the toys started displaying their agency in front of humans would they be retired by bounty hunters? Would the Clones? I think they would, though there would probably be liberationist sympathizers among the humans for both cases.

rm 06.21.10 at 6:27 pm

Keith, I can’t see both as “manufactured lifeforms with agency,” though if I could I would see your point. Genre comes into play. The premise of toys being alive is a fantasy trope; it works by magic. Clones are human, and the world of the novel is science fictional and plausibly real. Consequently readers are asked to see their agency and nature differently.*

I’m glad you brought up PKD’s Do Androids Dream. I’ve always read the novel (much less so the movie) as being about categories that see people as objects. The chickenheads, the andys**, the mentally ill, anyone “measured” by psychometric testing, women under the gaze of sexist men, are all dehumanized in the novel’s society. The animals, too, are devalued as independent beings. By extension the reader can think about racism and slavery while reading (think of Topsy in Uncle Tom’s Cabin, who is first introduced as a kind of wind-up toy who did not have parents).

The most uncomfortable aspect of Never Let Me Go, for me, was the place of the liberals who tried to make the clones’ lives bearable. They aren’t capable of facing up to the full horror of their society, any more than the clones are, because the reader’s perspective is unthinkable to those who have lived the alternate history. The liberals just try to mitigate the worst effects of the horror.

So, I think both Phil Dick and Kazuo Ishiguro (much more subtly, of course) are suggesting that we dehumanize people in ways we’re hardly capable of even examining, and that this is a big problem. I just don’t think Toy Story approaches the same themes, because the genre is fantasy and the artificial actors are truly artificial, not just socially constructed as such. There’s a difference between f and sf, and there is also a difference (if the genre distinction doesn’t matter) between a biologically manufactured person and a possessed doll.

*The problem is all of you philosopher people read like philosophers, and don’t account for literary effects like genre. You people, I swear.

**It is surely, surely pure coincidence that the toys’ owner is named Andy . . . right? Right? Then again, those early CGI people didn’t look quite human . . . .

Keith 06.21.10 at 6:47 pm

rm@23: OK, the genre shift does make a distinction, I agree. Mostly the toys serve as allegorical stand-ins for people who are enacting a narrative with a moral center that lies outside of the same purview as NMLG (or DADOES). Toy Story is all bout how we deal with growing up and loss and finding our place in the world, whereas both Never Let Me Go and Androids are about how we dehumanize ourselves in order to make a broken society function. Toy story is far more optimistic in this regard. The toys happily accept their fate as slaves*, while the clones and Andys do not.

_________

*Except for Stinky Pete who wants to be put on display and adored like an idol for having the accidental status of purity.

chris 06.21.10 at 7:27 pm

There’s no categorical difference. Both are manufactured lifeforms with agency.

Aren’t you implicitly assuming that the agency of those beings is no different from the agency of humans? This may make sense for human clones (I haven’t read NLMG but it’s clearly not the only SF to deal with clones and their potential place in society), but is rather more questionable for toys. What is the xenopsychology of toys, and how is it relevant to morally evaluating a human/toy society?

lemmy caution 06.21.10 at 7:46 pm

the lamp

Keith 06.21.10 at 10:02 pm

Chris@25: Aren’t you implicitly assuming that the agency of those beings is no different from the agency of humans?

I am saying just that. The clones and toys have human agency, just exist in worlds where the social conditioning of both groups restricts them from behaving as fully self-realized actors. As far as we know, it’s conditional and self-imposed in both cases.* The clones have been conditioned to believe they have certain restrictions on their freedoms and the toys all silently agree to behave in a certain manner around humans, effectively giving up their autonomy as long as a human is around (except in extenuating circumstances and even then it’s referred to explicitly by Woody in the first movie as breaking the rules).

_________

*I haven’t read NLMG, so I’m responding only to what I’ve heard of the story. I could be way off with the clones, if they were somehow programmed to be subservient.

pv 06.21.10 at 11:43 pm

“highly intelligent, potentially autonomous creatures who define their happiness entirely in terms of the happiness of others”

Others have brought up animals, and I think perhaps the comparison of the toys to animals is relevant. However, in the case of humans dealing with animals, it is not the animals that define their happiness in terms of our happiness, but we who usually define their purpose, their reason for being, in terms of our own happiness. That could make a viewer “queasy” too, thinking of the ways we define the purpose of animals in terms of our own pleasure (for food, for pets, for entertainment, for sport).

But I also think there’s something slightly deranged about the massive amount of anthropomorphic and and personified animals in childrens’ movies and tv, in a culture where consuming those animals for pleasure is so commonplace.

Chris 06.22.10 at 12:27 am

I am saying just that. The clones and toys have human agency, just exist in worlds where the social conditioning of both groups restricts them from behaving as fully self-realized actors.

There’s no basis for making that statement about the toys, though — other than overstretching an analogy derived from the fact that some of them have humanoid appearance, maybe. They could have (and apparently do have) agency that is quite different from human agency.

rm 06.22.10 at 2:24 am

This brings to mind the novels The Sparrow and Children of God by Maria Doria Russell. There is a planet with two sentient species that [{***spoiler***}] have evolved in parallel as predator and prey. The society is dominated by a small number of the predator species, who rule over herds of intelligent people that do all the work and then, when they are middle aged, submit quietly to be slaughtered and eaten. In the second novel {{(*******{[mega spoiler]}*******)}} the prey rebel. The surviving predators convert to Judaism and learn from Jesuits how to eat non-sentient meat.

So, anyway, interesting.

rm 06.22.10 at 2:39 am

The toys in Toy Story are not separate from Andy — they are parts of his psyche. In fantasy, the landscape and everyone in it are projections of the hero’s soul and mind, or else they represent a spiritual test of his character. That’s why it doesn’t matter that they are devoted to Andy; the conflict is whether or not to accept the changes that come with time and age, without going astray developmentally. Andy could hold on to childhood delusions (Buzz not realizing he’s a toy), or grow into an old, bitter man who never progresses beyond some childhood stage (Stinky Pete), or develop compulsions (the dinosaur), or live with a sense of loss and regret for childhood past (Jessie when she won’t get over her girl). His fears are represented by Woody, who faces them and arrives at a healthy attitude.

So I don’t think that compares well to the SF narratives where the clones/androids/aliens/AIs/talking animals are really Other — other minds that we might be tempted to objectify for our convenience. They are definitely not mere projections of some main character’s spiritual state.

Chris 06.22.10 at 11:39 am

The toys in Toy Story are not separate from Andy—they are parts of his psyche.

Well, that’s an unusual interpretation, certainly. Andy never even meets Stinky Pete, or Zurg, and Jessie is walking around doing things long before Andy ever sees her, for one thing.

In fantasy, the landscape and everyone in it are projections of the hero’s soul and mind, or else they represent a spiritual test of his character.

This seems, um, overambitious. It may describe *some* fantasy, but all of it? Really?

Let’s take a well-known example that happens to be on my mind because it was recently discussed on Tor.com: _Nine Princes in Amber_. (And the series generally.) Clearly, the landscape isn’t a projection of Corwin’s soul and mind — we know this in two ways, first because it *is* a projection of Dworkin’s soul and mind, but Dworkin is neither a hero nor even a viewpoint character, and second because Corwin does eventually create a world that is a projection of his soul and mind and it’s different enough from Amber that it endangers the stability of the multiverse.

So, that leaves a spiritual test of his character. There might be a makeable argument for this, but only in the sense that many narratives (including nonfantasy ones) include tests of the hero’s character because the author writes them that way. That seems like a weak reed with which to label an entire genre (especially one as unrestrained in its variations as fantasy).

Philip 06.22.10 at 12:32 pm

What about the cow in the Restaurant at the End of The Universe that is bread to tell diners how much it wants to be eaten?

Philip 06.22.10 at 12:34 pm

bread -oops, whycan’t I edit my post?

noen 06.22.10 at 5:04 pm

“Babe” and the End of Analysis

For my money the movie “Babe (1995)” is by far the best treatment of these issue that I’ve seen.

And sooner or later, every toy gets discarded.

Ginger Yellow 06.22.10 at 5:06 pm

Philip: it’s food for thought, certainly.

ajay 06.22.10 at 5:11 pm

What about the cow in the Restaurant at the End of The Universe that is bread to tell diners how much it wants to be eaten?

I don’t regard Douglas Adams as a very reliable sauce.

noen 06.22.10 at 5:13 pm

Tag fail! :((((

Anyway, the fact that in Toy Story 1 & 2 (I’ve yet to see 3) the toys never truly confront their fantasies and understand them for the delusions they are is telling. America lives in a collective dream world. Even now we cannot face the reality of what is happening in the Gulf and what it’s implications are for our future. People still cling to their delusional fantasy construct that their owners love them and want the best for them.

This illusion needs to die.

Michael 06.22.10 at 6:22 pm

lemmy caution @ 26: yes, that’s precisely what capitalism wants you to think. The lamp has no feelings! Buy another one that is much better!

noen @ 38: the fact that in Toy Story 1 & 2 (I’ve yet to see 3) the toys never truly confront their fantasies and understand them for the delusions they are is telling

Um, you missed the whole entire Buzz Lightyear plot of TS1? Relatedly, the moment in A.I. when David realizes he is one of an advanced line of cyborgs (start at 4:25 if you’re pressed for time) is precisely the moment in TS1 when Buzz realizes he’s a mass-produced toy. Here’s TS2 wittily revisiting that moment (at 4:55). Note the line, “tell me I wasn’t this deluded.”

Ragtime 06.22.10 at 6:32 pm

I opposition to Toy Story and Never Let Me Go, allow me to recommend “The Doll People” series of children’s books.

In these books, The Doll People are essentially identical to the “Toys,” with several relevant exceptions.

A. Dolls are given the option of becoming “Living Dolls,” and promising to obey the Doll Code, or not. Barbies, for example, never take the oath, so are just “regular dolls.”

B. If a person sees or suspects that a Doll is a living doll, the doll is put into “Doll State” — 24 hours of paralysis — so there is a reason for keeping the kids from seeing them move. There is also the constant threat (no one knows if it’s real or not) or “Permanent Doll State” for serious infractions.

The Dolls still love being dolls, but do not exist solely for the kids — much of the conflict is about how much risk it is reasonable to take when the kids are asleep or at school for their own self-fulfillment.

noen 06.22.10 at 6:57 pm

Michael @ 39

Um, you missed the whole entire Buzz Lightyear plot of TS1?

It’s been a very long time. I saw it in the theaters at the time and that’s about it. Still…. it seems to me that the characters in the Toy Story franchise never really confront their true existential dilemma. They might do so glibly and in the service of a joke but not seriously. Or that’s what I recall. At the ends of both TS 1 & 2 they are happy toys happy to be useful and in service to their owners.

“Oh to be a machine, oh to be wanted, to be useful”

This is the desire of the toys in Toy Story. With no sense of the horror of what that really entails.

Michael Bérubé 06.22.10 at 7:05 pm

With no sense of the horror of what that really entails.

OK, point taken, but the contrary point is that the other options are even worse: (1), Buzzian delusion that one is not in fact a toy (and can fly, and has lasers that work, etc.), and (2) abandonment (hence the pathos of Jessie’s “When Somebody Loved Me,” which changes the whole tenor of TS2).

chris 06.22.10 at 7:55 pm

With no sense of the horror of what that really entails.

Who says it’s horrible to a toy? You’re just projecting your own psychology onto the toy and perceiving that you would be horrified by being in that situation.

rm 06.23.10 at 2:38 am

Chris @32:

Andy never even meets Stinky Pete

You’re so literal-minded; sheesh. Andy and the home crew are characters, so they do act on their own motivations (and some are just comic relief) and go on their own adventures. But they also represent lessons in morals and character that are relevant to Andy. Stinky Pete is an object lesson in control problems and unhealthy nostalgia for a lost childhood — he’s relevant to Andy thematically. Good fantasies can be taken literally first, and have flexible, mutable, not very strict levels of symbolism and allegory that present themselves on later reflection.

some fantasy, but all of it?

No, of course not. No generic description fits every example. What I mean is that fantasy as a genre is deeply related to Arthurian myths and other medieval fantastic narratives (e.g. saints’ lives) in which the landscape is, indeed, a moral testing ground, a crucible for alchemical refinement of the soul, rather than a real-world setting with naturalistic rules. This kind of setting has been updated in literature countless times (Natty Bumppo, Philip Marlowe, Harry Potter), and it’s more often true of a fantasy story than not. The Amber series is very original and atypical, so I don’t think it makes a good counterexample to a generalization, though it’s a great example of how fantasy does not have to always do the same things.

I think the plots of Toy Story 1 and 2 are so driven by characters’ internal passions that the stories do become a sort of internal psychodrama. They are about growing up, and Andy is the only one of the gang that is actually growing.

Noen @35 on Babe: I’d forgotten! That’s such a brilliant scene.

chris 06.23.10 at 1:40 pm

Good fantasies can be taken literally first, and have flexible, mutable, not very strict levels of symbolism and allegory that present themselves on later reflection.

Well, I think that that kind of hermeneutics is often more of a Rorschach test than anything else.

I could equally well say that Stinky Pete’s *real* problem is self-esteem — he doesn’t value himself except as part of a complete set that includes Woody, and that’s why he feels threatened by Woody’s refusal to join the set, when really he should learn to be himself and not depend on Woody and the others to complete his self-image.

the landscape is, indeed, a moral testing ground, a crucible for alchemical refinement of the soul, rather than a real-world setting with naturalistic rules

This seems like a false dichotomy — isn’t there plenty of non-fantasy fiction with ostensibly naturalistic settings that just happens to arrange itself (or rather, be arranged by the author) to test the hero’s character? The importance of character and character development to fiction and how all the events of the narrative are viewed through the lens of the characters who experience them seem to me to cut across genre lines.

Also, I’m not sure it’s accurate to refer to saints’ lives as fantasy — if the authors and audiences actually believed in miracles, they’re not a fantasy element in the modern sense. The distinction between fantasy and naturalistic fiction can only be made when there is a delineated naturalistic worldview to use as a ruler, so to speak.

We define _Toy Story_ as fantasy because we don’t believe in animate toys, but if someone does believe in saints who perform miracles, then a story about saints performing miracles isn’t fantasy, to them.

Comments on this entry are closed.