*Capital in the Twenty-First Century* was a classic as soon

as it was published.[^21] It deserves a place on bookshelves beside its

illustrious namesake of the 19th century. Capital, in

*Capital*, is the wealth of nations. It extends beyond

firms’ traditional productive capital to encompass the entire public and

private patrimony that can be sold on a market (thus excluding

non-transferable forms of capital such as human, cultural and social

capital). The book is the culmination of fifteen years of individual and

collective research on the evolution of income and wealth inequalities.

Thanks to data based on the collection of income tax, Thomas Piketty and

his colleagues had already widely explored income inequality in France,

the United-States, India, China, and more generally in the world by the

early 2000s, fuelling a unique and remarkable dataset: the *World

Top Incomes Database.* However, this work focused on income

rather than wealth, and hence provided an incomplete account of economic

inequality. This new book fills in this gap in a very timely fashion.

The thesis of the book could be summarized as follows: the simple fact

that the return on capital is durably higher than the economic growth

rate feeds implacable dynamics of inequality.

Under these conditions, the relative share of capital (as measured by

the national wealth to GDP ratio) increases inexorably. Far from being

exceptional, this configuration is currently the norm. Since the 1970s,

the decline in the growth rate which is a combination of the decline in

the population’s growth rate and that in individual productivity, have

helped capital come back. In France, the amount of total wealth owned by

all public and private actors has gone from a little less than four

years of income in the 1970s to more than six in the 2010s.

This resurgence of capital promotes increased inequality in several

ways. First, wealth is very unevenly distributed, with the poorer half

of the population holding less than 5% and the top 1% holding 25%. The

global increase in asset prices thus tends to help the latter. Second,

ability to save, and hence to accumulate wealth, increases with income.

Third, the higher the wealth, the greater the return on capital, thanks

to better financial advice, a weaker preference for liquidity and a

greater ability to bet on more remunerative (albeit risky) long term

investments. Meanwhile, the increase in wage inequality, due to the

emergence of “super-wages” for an elite of CEOs and finance

professionals, enables newcomers to find a position among the wealth

elite without weakening this elite’s domination.

After reaching a low point in 1970, wealth inequality is on the rise

again. The share of national wealth owned by the top 1% increased from

28% in 1979 to 34% in 2010 in the United States, from 23% to 28% in the

United-Kingdom and from 22% to 24% in France. It is still a long way

away from the concentration of wealth in the early 20th century where

the top 1% had 60% of national wealth in France and 70% in the UK.

However, *Capital* warns us that we may be on our way back

to that world if the dynamic of inequality is not halted. According to

Piketty, progressive taxation of income and capital (on the level of

global regions to limit the problem of tax competition) could set the

net return on capital below the economic growth rate and halt the

inequality dynamics.

But the book goes far beyond a simple demonstration of the unequal logic

of capitalism and the merits of redistributive taxation. It is a

remarkable multidisciplinary work on the economic and social history of

Western capitalism and inequalities, thanks to a combination of serial

statistics and specific examples from literature, film, political

history and history of economic thought that illuminates both past

events and perceptions. Wealth is the gateway to a new understanding of

two centuries of economic, social and political history. The opposition

in the nineteenth century between the Old World, dominated by past

wealth (with a capital equivalent to seven years of income) and the New

World, less subject to such a legacy (with a capital of less than five

years of income) is particularly striking. So is in the opposition in

the New World between the North of the United States and the South,

where slave ownership gave capital a preponderance similar to that

measured in Europe at the same period. The shocks of economic crises and

inflation peaks, the impact of fiscal policies, sometimes offensive,

sometimes accommodating, and moreover the destruction of wars greatly

shape the importance and the role of capital.

The book sometimes adopts a Braudelian tone, highlighting deep

structures of capitalism, such as the growth rate, that are unbudging

and impossible to guide. The decades of growth in the postwar era is an

exceptional stage that is futile to feel nostalgic for and try to return

to, since it was largely a phase of reconstruction and catch-up. After

reaching the technological frontier, growth can only continue in the

21st century at its long-term rate of 1 to 1.5% per year (of which half

is due to population growth). It seems slow when measured year by year,

but it is very fast and almost unbearable at the scale of centuries. In

addition to the growth rate, other factors such as the savings rate,

share of value added, and return on capital are also immobile or slowly

changing variables that seem to defeat any kind of political action. If

these quantities, which are the product of a kind of extended general

equilibrium, are not controllable, states still retain their two

original powers to shape capital accumulation and its unequal

consequences: wars (which one cannot want) and taxes.

Although the book contains many impressive and valuable statistical

series, it takes some risks in its treatment of the largely unexplored

topic of wealth. These first estimates will benefit from being

evaluated, tested, and corroborated by later work. For example, the

return on capital, which the author believes to be stable at around 5%,

is calculated from aggregate data from national accounts and defined as

the ratio between the share of capital in the value added from the

income accounts and the estimated value of the national capital in the

wealth accounts. Given the numerous conventions that govern the

construction of these data, the reconciliation of the macro approach

with a micro approach might add a lot, all the more so as the

performance of listed shares varies considerably even in the

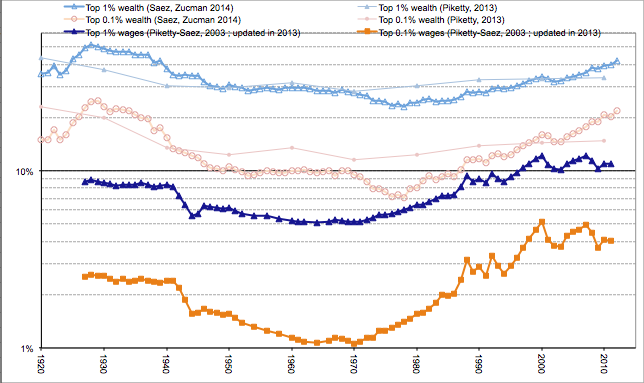

medium-term. The ten-year yield (including capital gains) of the S&P500

(the index of the New York Stock Exchange) is greater than 10% between

1940 and 1960 and between 1980 and 1992, while it is negative or zero

between 1965 and 1975 or since 2000 (Figure 1). These significant

variations in performance at the micro level leads one to ask whether

the resurgence of capital is due to the inexorable mechanics of

capitalism or rather a product of contingent financial and real estate

bubbles, and more generally due to the phenomenon of financialization.

Answering this question could tell us whether, in addition to fiscal

policy, a sector-based economic policy of “definancialization” could

also contribute to fight inequality.

Figure 1. Comparison of the return on capital over ten years calculated

by Thomas Piketty and that on some US famous assets. Note: A portfolio

replicating the S&P500 purchased in 1949 and sold in 1958 provides a

real annual return of 18% per year (capital gains included).We discount

changes due to inflation. Sources: Thomas Piketty’s data is available

[here](http://piketty.pse.ens.fr/files/capital21c/Piketty2013GraphiquesTableaux.zip);

those on yields of major US national assets

[here](http://pages.stern.nyu.edu/~adamodar/New_Home_Page/datafile/histretSP.html).

While the early work of Thomas Piketty and his colleagues focused mostly

on income inequality due to the emergence of a new elite, the Working

Rich, this new work focuses on wealth and offers a very different

diagnostic by showing the resurgence of capital in its most traditional

form: inheritance. The various forms of inequality are morally and

politically ranked by the frequent use of the concept of merit, a

concept difficult to define – and not specified here – sometimes used to

describe the collective perception (an emic conception), sometimes that of the

analyst (an etic conception). According to the author, wealth inequalities

(particularly those that are inherited) violate merit more than income

inequality, which contravene merit more than wage inequality.

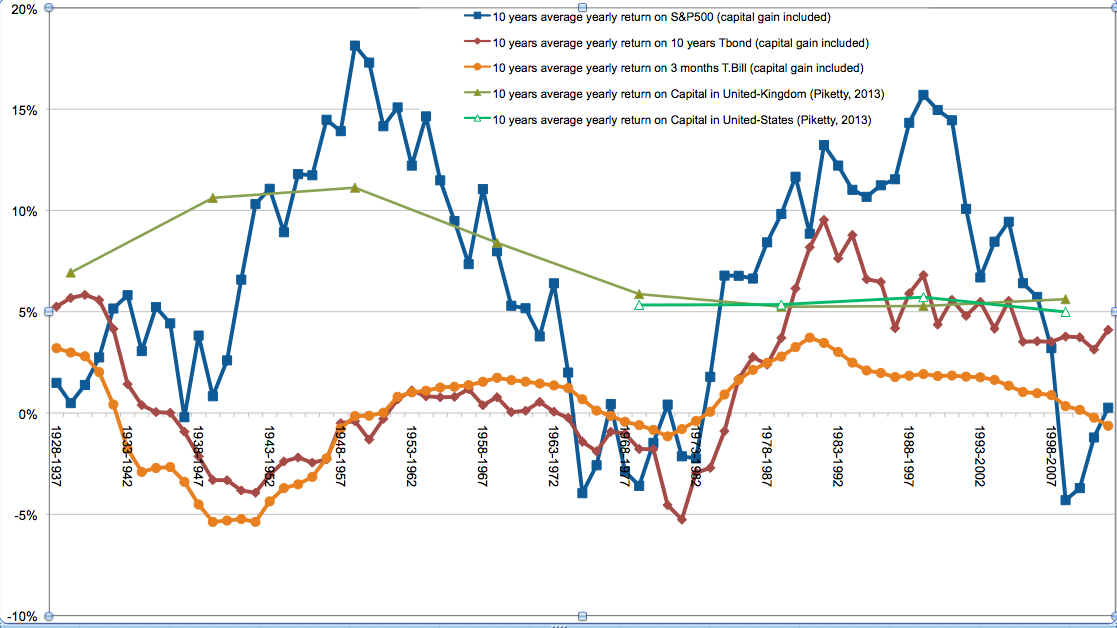

Although the resurgence of capital is a proper cause of concern,

especially for political and moral reasons, should we consider it as the

most prominent transformation of contemporary inequalities? Certainly,

wealth inequalities are more pronounced than income inequality. But in

light of the data presented, their recent growth in the US is much more

limited than that of wages. In 2010, the share of the top 1% in wealth

is 1.3 times larger (in terms of odds ratios) than it was in 1970. Over

the same period, the share of the top 1% in wages increased by a factor

of 2.3. Measured by this yardstick, the emergence of the Working Rich is

a more radical transformation than the resurgence of capital. However,

it seems that the author, rigorously reasoning his way through

incomplete data, has had the remarkable intuition of a phenomenon that

the available data only showed imperfectly.

Hence, in a recent work, Gabriel Zucman and Emmanuel Saez (2014)

reestimate wealth composition from income tax. This method requires one

to make many assumptions to estimate stocks from flows and we must

remain careful. Nevertheless, they establish remarkable results that

fill in the missing piece of Thomas Piketty’s book. According to these

new estimates, the top 1%’s share of wealth has increased 1.5 times

between 1970 and 2010, moving from 28% to 37% of total US wealth and

that of the top 0.1% increased by 2.3 between 1970 and 2010, moving from

10% to 20%. If Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman’s work holds true, then

there is indeed a real resurgence of wealth inequality, moving back to

its 1920 level. Nevertheless this is smaller in relative amplitude than

the rise of the Working Rich: the share of the top 0.1% of wages

increased during the same period by 3.9, moving from 1.1% of payroll to

4.1% (Figure 2). It is true that the interpretation of the comparison of

two evolutions of percentage depends dramatically on the choice of the

metric: additive (+10 percentage points for wealth versus +3 percentage

points for wages) or multiplicative (as I do here: \*2.3 for wealth

versus \*3.9 for wages). However, whatever the metrics, the complexity

of recent changes in inequality is due to the necessity to think them as

both the product of the return of capital and the rise of the Working

Rich.

Figure 2. Comparison of the evolution of wealth inequality and wage

inequality in the United States

Note: The top 0.1 wage share amounted to 1.1% of payroll in 1970.

Sources: for

[salaries](http://eml.berkeley.edu/~saez/TabFig2012prel.xls); for

[wealth](http://gabriel-zucman.eu/uswealth/SaezZucman2014MainData.xlsx).

[^21]: An earlier version of this was published in French as Godechot

Olivier, 2015, “Le capital au XXIe siècle, T. Piketty.” Le Seuil,

Paris (2013). 970 pp., *Sociologie du travail*, vol. 57, 2, p.

250-253.

{ 4 comments }

Rakesh Bhandari 12.16.15 at 3:41 pm

On supermanager income, it is however, in the nature of things, for it to soon become the compounding wealth of a rentier and for those rents to become greater than income.

On the S&P Chart, I could not figure out what the olive line is representing. I am not sure what the green line is either.

Don’t know how the portfolios of the wealthy have changed. We would have to chart corporate bonds too. Weren’t those a bigger part of portfolios in the 60s? Did the corporate bonds that the wealthy tended to own compensate for weak returns in the S&P 500? And even in terms of stock indices were the wealthy able to beat the averages, especially when low?

Also even if r =g, the wealthy could get wealthier due to higher-than-average returns. Again we could look at the University endowment data.

In terms of stock performance in the decades after WWII, Piketty also does say that it took some time up after the depression of capital values from the War for the catch up effect to really take hold.

Peter T 12.16.15 at 8:43 pm

CEO compensation may be formally a wage. In practice, it’s just the currently-preferred form of income extraction from the common pool. Earlier centuries (or other places) would not have found it remarkable – elite incomes in, eg, the C16/C17 were often a mix of rents, state salaries and state-granted monopolies.

Cleric 12.16.15 at 10:03 pm

I’m curious:

“This method requires one to make many assumptions to estimate stocks from flows and we must remain careful.”

What might those assumptions be, and what must we remain careful about before jumping into the conclusion that…

“they establish remarkable results that fill in the missing piece of Thomas Piketty’s book”?

T 12.17.15 at 12:19 am

@2 @3

Peter T — Also, individuals would attempt to shift compensation from higher taxed categories to lower taxed categories, i.e. wages to cap gains or from short-term gains to long-term gains. And wealth measurements by individuals are tricky because cap gains are reported on sales of assets, not on held assets (the flows vs stock issue). Several recent studies have shown a significant share of income and wealth is effectively hidden. But this is the type of work that must be done to get the best estimates.

Comments on this entry are closed.