From the monthly archives:

December 2015

Our friend Erik Olin Wright has s long essay on How to be an Anti-Capitalist at Jacobin. Read the whole thing here.

An excerpt:

The Four Types of Anticapitalism

Capitalism breeds anticapitalists.

Sometimes resistance to capitalism is crystallized in coherent ideologies that offer both systematic diagnoses of the source of harms and clear prescriptions about how to eliminate them. In other circumstances anticapitalism is submerged within motivations that on the surface have little to do with capitalism, such as religious beliefs that lead people to reject modernity and seek refuge in isolated communities. But always, wherever capitalism exists, there is discontent and resistance in one form or other.

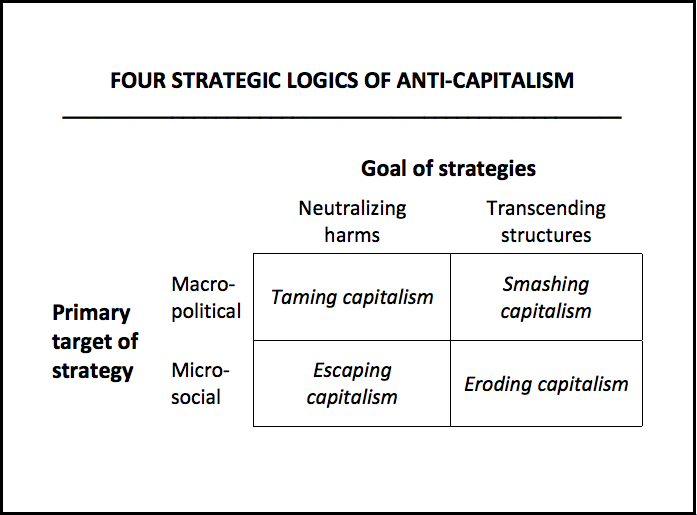

Historically, anticapitalism has been animated by four different logics of resistance: smashing capitalism, taming capitalism, escaping capitalism, and eroding capitalism.

These logics often coexist and intermingle, but they each constitute a distinct way of responding to the harms of capitalism. These four forms of anticapitalism can be thought of as varying along two dimensions.

One concerns the goal of anticapitalist strategies — transcending the structures of capitalism or simply neutralizing the worst harms of capitalism — while the other dimension concerns the primary target of the strategies — whether the target is the state and other institutions at the macro-level of the system, or the economic activities of individuals, organizations, and communities at the micro-level.

Taking these two dimensions together gives us the typology below.

Loyola University, a Catholic university in Chicago, is opposing a union drive among its contingent academic workers. On the grounds that it would violate the university’s First Amendment religious liberty.

What is at stake here, is Loyola’s guaranteed First Amendment rights of religious freedom and autonomy—essentially our right to define our own mission and to govern our institution in accordance with our values and beliefs, free from government entanglement. The United States Supreme Court long ago ruled that the First Amendment provides an exemption from NLRB jurisdiction in order to protect an institution’s religious liberty and identity. We are not alone in raising this issue, as religious institutions across the country have opposed NLRB jurisdiction in similar union-organizing situations on the same grounds that we have raised. Our position before the NLRB is not driven by anti-worker sentiment or hostility to organized labor. By raising the jurisdictional issue at the hearing, we are simply seeking to maintain our right to religious freedom, to protect the heart and soul of our institution and its mission.

Here’s what Pope Leo XIII had to say on the topic of labor unions and Catholic teaching in Rerum Novarum (1891):

The most important of all [workers’ associations] are workingmen’s unions, for these virtually include all the rest. History attests what excellent results were brought about by the artificers’ guilds of olden times. They were the means of affording not only many advantages to the workmen, but in no small degree of promoting the advancement of art, as numerous monuments remain to bear witness. Such unions should be suited to the requirements of this our age – an age of wider education, of different habits, and of far more numerous requirements in daily life. It is gratifying to know that there are actually in existence not a few associations of this nature, consisting either of workmen alone, or of workmen and employers together, but it were greatly to be desired that they should become more numerous and more efficient. We have spoken of them more than once, yet it will be well to explain here how notably they are needed, to show that they exist of their own right, and what should be their organization and their mode of action.

Ninety years later, Pope John Paul II reiterated that position in Laborem Exercens (1981):

All these rights [of workers], together with the need for the workers themselves to secure them, give rise to yet another right: the right of association, that is to form associations for the purpose of defending the vital interests of those employed in the various professions. These associations are called labour or trade unions….Their task is to defend the existential interests of workers in all sectors in which their rights are concerned. The experience of history teaches that organizations of this type are an indispensableelement of social life, especially in modern industrialized societies.

As did the National Conference of Catholic Bishops in their 1986 pastoral letter Economic Justice for All:

The Church fully supports the right of workers to form unions or other associations to secure their rights to fair wages and working conditions. This is a specific application of the more general right to associate. In the words of Pope John Paul II, “The experience of history teaches that organizations of this type are an indispensable element of social life, especially in modern industrialized societies.”(58) Unions may also legitimately resort to strikes where this is the only available means to the justice owed to workers.(59) No one may deny the right to organize without attacking human dignity itself. Therefore, we firmly oppose organized efforts, such as those regrettably now seen in this country, to break existing unions and prevent workers from organizing.

And just a few months ago, the Archbishop of Chicago had this to say on the topic:

Similarly, the Church has consistently taught that workers have a right to have a voice in the workplace, to form and join unions, to bargain collectively and protect their rights. And the Church has never made a distinction between private and public sectors of the work. It was not 4 Msgr. Higgins who called unions “indispensable,” but Pope, now Saint, John Paul II in his powerful and still timely encyclical “On Human Work’” Work and unions are important not simply for what a worker “gets,” but how they enable a worker to provide for a family and participate in the workplace and society. Unions are important not simply for helping workers get more, but helping workers be more, to have a voice, a place to make a contribution to the good of the whole enterprise, to fellow workers and the whole of society….Across the twentieth century and into the twenty-first, ten Popes have affirmed and expanded this very vision.

…

For example in view of present day attempts to enact so-called right-to-work laws the Church is duty bound to challenge such efforts by raising questions based on longstanding principles. We have to ask, “Do these measures undermine the capacity of unions to organize, to represent workers and to negotiate contracts? Do such laws protect the weak and vulnerable? Do they promote the dignity of work and the rights of workers? Do they promote a more just society and a more fair economy? Do they advance the common good?” Lawmakers and others may see it differently, but history has shown that a society with a healthy, effective and responsible labor movement is a better place than one where other powerful economic interests have their way and the voices and rights of workers are diminished.

…Ad [sic] I have to admit not every claim of religious freedom is valid and the law has to protect the basic rights of all.

…

The Archdiocese of Chicago employs 15,000 full and part-time employees in its agencies, seminaries, schools and parishes. We strive to be a just employer. I have asked our Archdiocesan staff to review all of our human resource policies to ensure we are practicing what we preach about the dignity of work and the rights of workers. We will work earnestly to address any gaps. After all, like everyone we also need to be accountable. Because the Archdiocese is an employer, some employees and some unions may want to organize in our workplaces. Some Archdiocesan employees are already organized and we work with their union to advance our mission and our mutual obligations to workers. Others are not. And that is because some “jobs” in the Church are really ministerial positions, and must answer to a higher law than those passed by legislatures, we may have differences in this area. But if we stay firm in our commitment to principled dialogue, we can resolve differences and move forward together.

The position of the Catholic Church on the right of workers to form trade unions, even within Catholic institutions (that exception that the Archbishop of Chicago carves out at the end of his address is pretty limited and certainly does not apply to adjunct instructors at a university that does not impose denominational or sectarian obligations on its faculty or students), is clear.

In the name of the First Amendment, in the name of a religious freedom to be Catholic and to follow Catholic teachings, Loyola claims the right not to be Catholic and to suspend Catholic teachings.

Story here.

Warning: Crappy past performance of media commentators is no guarantee of crappy future performance.

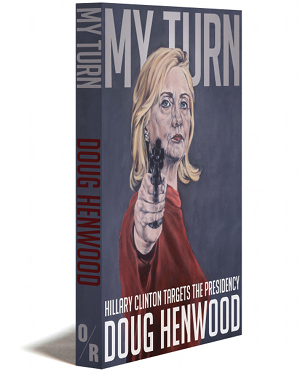

Below, I review, in usual rather semi-detached style, the book by friend-of-the-blog Doug Henwood on Hillary Clinton’s candidature for President. A capsule summary might be: he’s against it. I’ve posted the cover image below because it’s so fantastic.

[click to continue…]

Here’s the terrorist-sympathising MP John Baron:

Any successful strategy to destroy Isis hinges on there being a component of ground troops. Here the government makes the assumption that there are 70,000 Syrian moderates willing to take the fight to the organisation. While on our visit [Baron was part of a fact-finding mission to Middle-East capitals last month], we were reminded that, after nearly five years of conflict, there are precious few “moderates” in Syria. They do not form a coherent group; and, as the Americans found to their cost, they tend to be as liable to fight each other as they are to fight the extremists. The government has forgotten the lessons of Libya, where the anti-Gaddafi forces splintered into a thousand militias the moment the common enemy was defeated. A fresh civil war has been a result. Syria would be similar, but on a grand scale.

In any case, a feature of the Syrian civil war has been the speed at which new groups and organisations can spring from the shadows and stake their claim to support, legitimacy and territory. It is a bold assumption that the government’s strategy would prevent this, and the risks should be obvious that military intervention would merely clear the field for the next wave of extremists. We are all encouraged by the Vienna talks, but we are a long way off any lasting political solution.

The prime minister’s strategy is also notable for being heavy on emotion. We all sympathise with the French after the terrible attacks in Paris, and are mindful that such outrages could easily happen here, but we serve no purpose by allowing our thinking to be cloyed. When emotions run high, people tend to make mistakes. If parliament votes to intervene in Syria, it should not be in “solidarity” with our French partners – they know our sympathies are with them in any case.

Similar tired old lefty stuff from old Trot Matthew Parris, sounding smug at the Times:

‘If not now, when?” asked the prime minister this week: a question that has surely preceded some of the silliest decisions in history. It could have been asked before Iraq. It could have been asked before Afghanistan or Libya, or Suez. It was probably asked before the Charge of the Light Brigade. There is no right time for an unwise decision.

To a hushed House of Commons David Cameron brought the news that he had consulted his conscience. Politicians love interviewing their consciences; they reliably receive a supportive response. Tony Blair and his conscience got on famously: one of the longest-running romances of modern times. Let us have a little less about conscience and a little more about judgment.

Now must come a sentence I never expected to compose. Jeremy Corbyn is right.

One of the problems I have with the term “secular stagnation” is that it implies condition relevant to the very long term, say, the coming century. Such long run conditions presumably have to arise from fundamental causes in demography and technology. That’s the kind of argument that Piketty makes with his r > g theory of rising inequality. There are some good arguments for the view that the depressed state of the global economy, and particularly that of the more developed countries, can be explained in this way. But it shouldn’t be implied in the name of the problem. I’ve argued in the past that technology, specifically the Internet, doesn’t explain growing inequality,

The key quote from that New Left Project article, responding to Tyler Cowen’s The Great Stagnation

The global crisis stopped economic growth, not only in the US, but in countries far inside the technological frontier like Greece; while it had hardly any impact in, for example, Australia, which avoided the initial financial crises and used Keynesian fiscal stimulus to offset shocks flowing from the global economy.

A further reason for scepticism about technological stagnation is that this explanation has been advanced in recessions and depressions ever since the beginning of the capitalist business cycle in the nineteenth century. Such claims represent the flipside of the equally common claim, made during every period of sustained expansion, that the economy has entered a New Era of untrammelled growth. The most recent episode of this kind was the ‘irrational exuberance’ of the 1990s, fuelled by optimistic claims about the potential economic implications of the Internet, which was opened to commercial use by the US Congress in 1992, and by capitalist triumphalism exemplified by Fukuyama’s The End of History.The collapse of the ‘dotcom’ bubble was softened by the housing bubble that developed shortly afterwards (again, not at all a new phenomenon), but the result was only to worsen the inevitable crash in 2008. The similarity of these events to previous bubbles and busts is good reason to doubt that they represent, or that they have inaugurated, a new phase in the evolution of capitalism.