by Harry on June 16, 2017

Why do people keep saying that a bad agreement is worse than no agreement? They — not just May and her friends, but reasonably serious journalists — say it as if it means something. Isn’t it just the truism that an agreement that is worse than no agreement is worse than no agreement? Why is that observation relevant to anything? Everyone knows it is true, including the EU negotiating team. So the EU negotiating team is not going to try for a worse-than-no-agreement agreement, because they know that if that is the best on offer the UK can just walk away into WTO rules. So the observation that a bad agreement is worse than no agreement has no bearing on anything that anyone should do.

I’m missing something, right? [1] What is it?

[1] Really. I’ve been puzzling about this a while. I suppose an email to Henry should clear things up, but its more fun to open it up on CT, even at the cost of exposing myself as obtuse, which I obviously am being.

by Chris Bertram on June 16, 2017

This is a guest post by Chris Brooke

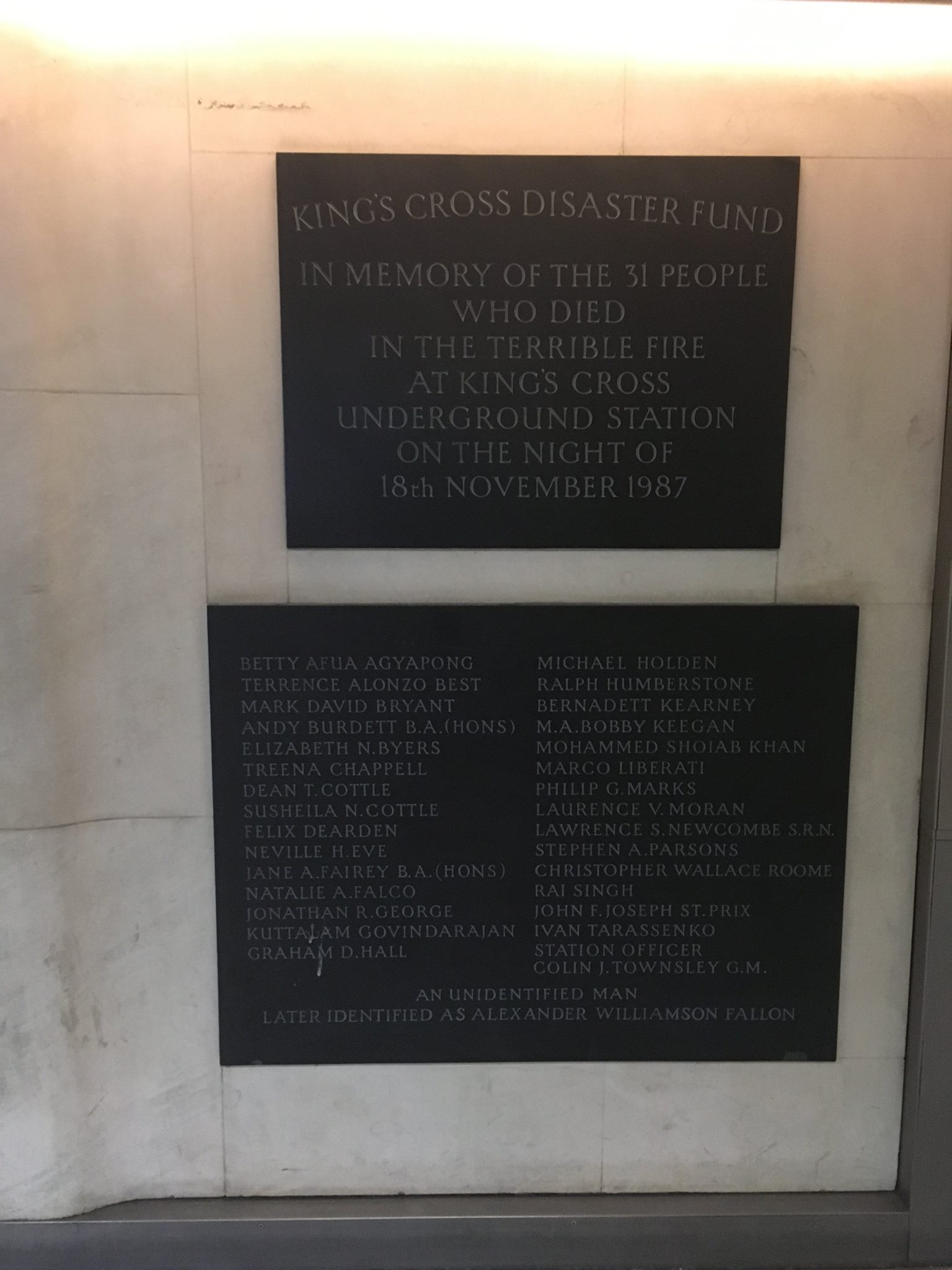

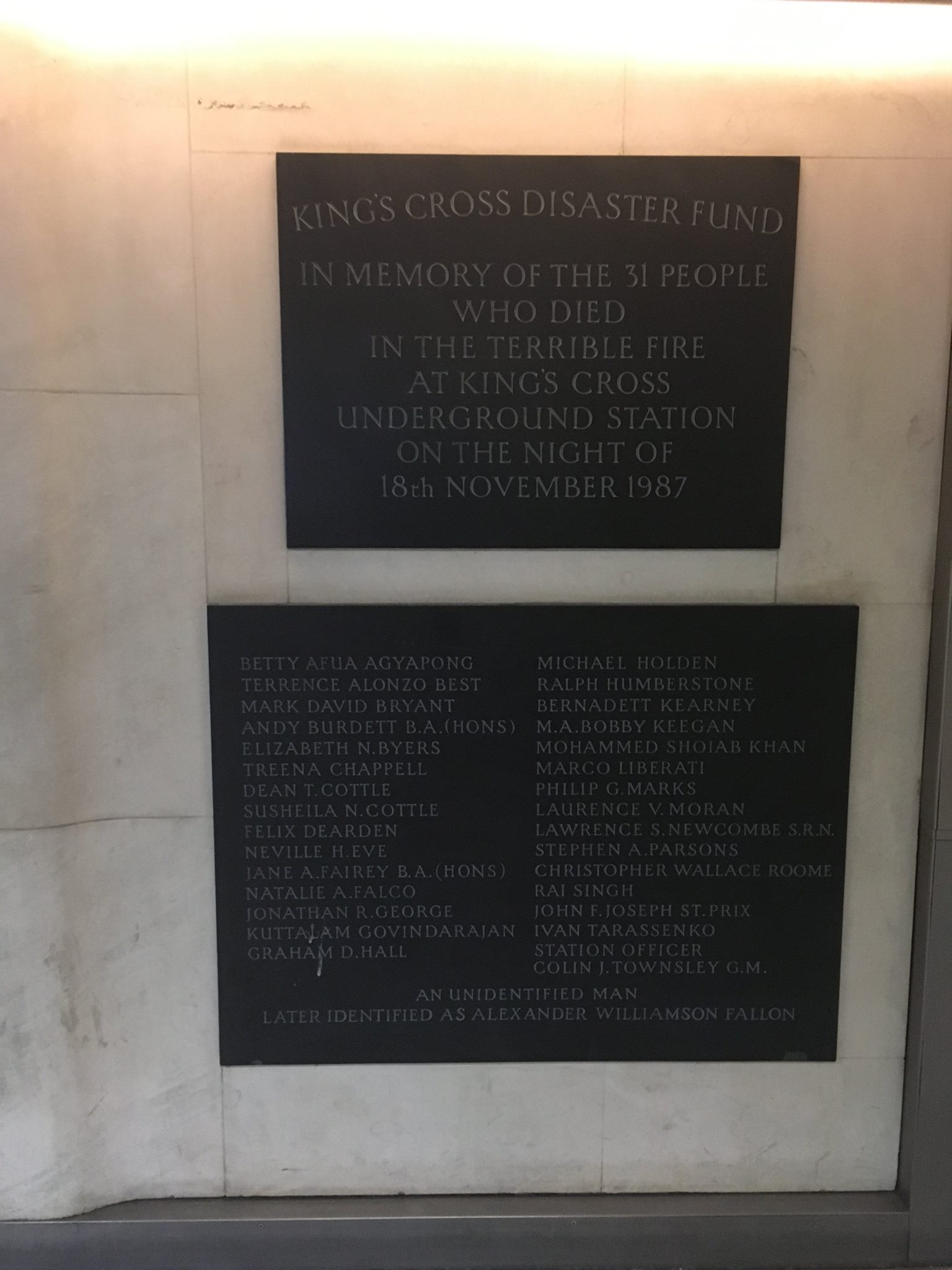

I spend my life shuttling back and forth on the train between Oxford and Cambridge. That means that twice a week I walk past the plaque at King’s Cross that memorializes the thirty-one dead of the fire of 18 November 1987. And when I walk past that plaque, I’m reminded of a distinctive moment in my younger life—not just King’s Cross, but also the fifty-six dead of the Bradford stadium fire disaster (11 May 1985), the one hundred and ninety-three who died on the Herald of Free Enterprise (6 March 1987), the thirty-five who were killed at Clapham Junction (12 December 1988), the ninety-six who were crushed at Hillsborough (15 April 1989), or the fifty-one who drowned on the Marchioness (20 August 1989). Perhaps it was coincidence that these catastrophes happened cheek by jowl, in a way that they just haven’t since. Or perhaps much of it was something to do with the ascendant political ideology of the time, that starved vital infrastructure of much-needed investment, and that celebrated the quick search for profit. One of the good things about living in England over the last quarter century is that this run of disasters came to an end, and things became quite a bit safer. But of course the predictable consequence of the politicians’ collective choice to embrace the economics of austerity over the last seven years—and even more so when it is conjoined with the Tory fondness for the execrable landlord class, a widespread dislike of safety regulations, the cuts in legal aid, and the politics of the majority on Kensington & Chelsea Council, especially when it comes to housing—is that we would regress in some measure to this second-half-of-the-1980s world, and everything that is coming out now about the Grenfell Tower saga suggests that we have so regressed.

Back in those 1980s days, there was a running joke that Margaret Thatcher would always pop up at the bedside of the victims, doing a somewhat ghoulish Lady of the Lamp act, and Private Eye printed a Thatch Card, on the pattern of the then-popular NHS Donor Cards, that said that in the event of being involved in a major disaster, the holder of the card in no circumstances wanted to be visited by Mrs Thatcher in hospital. Compared to the behaviour of her successor, however, Mrs Thatcher comes across as a paragon of democratic responsibility. Mrs May didn’t have to do much yesterday, but she did have to visit Grenfell Tower, talk to the residents—the survivors—and tell them that from henceforwards things were going to be OK. And she didn’t even do that. In a sense, we shouldn’t be surprised. Her authority was destroyed by the vote of 8 June, and she’s been in shell-shock since, starting to count down the days until she leaves office, insofar as it is practically inconceivable that she will lead the Conservative Party into the next general election and no-one is afraid of her anymore. But a zombie government is still the government, the Spiderman principle applies, and Theresa May is a coward and a disgrace.

by Belle Waring on June 16, 2017

The NYT today has an article about how the Dutch, with their long experience of holding back the sea, plan to advise other nations about utilizing children’s pudgy fingers to avert devastating floods. At least, I assume that’s what it’s about; I didn’t RTWT yet. More interesting and pertinent to me was this article from some weeks ago about how Singapore is constructing new land, both to increase the city state’s area on general principles and to deal with rising sea levels. Singapore is in a difficult position as a low-lying polis with no higher ground or inetrior countryside to relocate to. In addition, it is forested with high-rise apartment blocks that can hardly be moved. Bukit Timah hill, which I can see from my window, is only about 400 ft above sea level and is the highest point on the island. Singapore imports tons of sand from neighboring countries and uses it to create new islands offshore or infill and extend the current island.

The area where the Marina Bay Sands hotel and casino is located is on infill. It’s the one that looks like a cruise ship plonked on top of three curving towers. Next to it are these fabulous tree-like structures filled with plants and a stylized lotus building, and the huge ferris wheel, currently the biggest in the world, is nearby. With this and the durian-shaped Esplanade theatre Singapore has methodically achieved its goal of having a recognizable skyline. It is just like the government to plan the whole thing out like in this way after, one assumes, envious comparisons to the spontaneous towers of Hong Kong, and build it up in a slow plodding way–but then have it actually work!

From what I have seen in staying here so long, after the sand is put in, the ground is usually firmed up by being planted with trees for a while, though apparently they also build concrete honeycombs to support it from beneath. Both Indonesia and Malaysia have become irritated by the expansion and have begun to withhold exports of sand, so that Singapore has to look further afield. Myanmar has no compunction about selling something that’s worthless to them. Singapore has created something I didn’t know about, namely a strategic sand reserve in Bedok. This is also the most Singapore thing ever. Looking ahead! 10-year plans for new public housing and new MRT lines to service them! It is a curious place. I recommend you do read the whole article though it is long. The stories of a man who has viewed all the changes from the water are very interesting for a different perspective than the one I see. It is a fascinating look at what a truly endangered nation will do when it takes the Anthropocene seriously.