A couple weeks ago I was, as one does, declaiming selections from Erasmus Darwin’s poetry around the table, for the moral edification of the females present. I was explaining to the young daughters, in particular, how and why people were upset that Darwin poetized plants having sex all the time in The Botanic Garden, volumes 1 and 2. Especially volume 2.

The younger daughter: Oooh, fifty shades of green!

They grow up so fast.

When you actually read it, it makes a bit more sense that it bothered people. Because it isn’t just that plants reproduce, hence ‘breed’ – you kind of figure farmers and gardeners had noticed before Darwin pointed it out. It’s that the sex is hot! Plants are really sowing their wild oats a lot of the time, if you know what I mean. It’s all this polyamory and polygamy and sleeping around stuff. It’s like Tinder, but for plants. Volume 2 opens with a classification according to how many males and females are involved in any given case. And it gets a bit fetish-y in other ways.

With strange deformity PLANTAGO treads,

A Monster-birth! and lifts his hundred heads;

Yet with soft love a gentle belle he charms,

And clasps the beauty in his hundred arms. Â Â Â Â Â Â Â

So hapless DESDEMONA, fair and young, Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â

Won by OTHELLO’S captivating tongue, Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â

Sigh’d o’er each strange and piteous tale, distress’d, Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â

And sunk enamour’d on his sooty breast.

Project Gutenberg will do it for you. You can also get free Kindle versions from Amazon, if that is more convenient. Typography leaves something to be desired in all these cases. But no brown papers wrappers needed, like if you bought it in a store and didn’t want anyone to know. (I’d like this book but it’s annoyingly expensive. I suppose my scholarly needs shall drive me to it.)

If you don’t know who the hell Erasmus Darwin was, maybe start here.

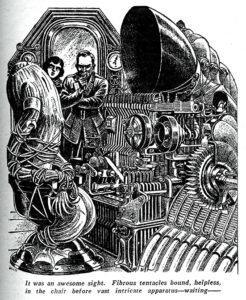

As I was saying, kinky plant tie-ups and science fiction is a natural combination. Plus monsters. Obviously that is why I was forcing this stuff on my immediate family.

(Illustration by Dold. Don’t know the original context.)

There are interludes, between the poetic bits, where Darwin engages in a dialogue with a ‘bookseller’. He explains what he thinks he’s up to, artistically. Obviously I’m interested in the degree to which it sounds like he is not just feeling but thinking his way towards a science fiction-y literary aesthetic. I’m also currently writing about thought experiments and science fiction (per my recent posts.) So anything that touches that interests me. For example, this bit:

Bookseller. The monsters of your Botanic Garden are as surprising as the bulls with brazen feet, and the fire-breathing dragons, which guarded the Hesperian fruit; yet are they not disgusting, nor mischievous: and in the manner you have chained them together in your exhibition, they succeed each other amusingly enough, like prints of the London Cries, wrapped upon rollers, with a glass before them. In this at least they resemble the monsters in Ovid’s Metamorphoses; but your similies, I suppose, are Homeric?

Poet. The great Bard well understood how to make use of this kind of ornament in Epic Poetry. He brings his valiant heroes into the field with much parade, and sets them a fighting with great fury; and then, after a few thrusts and parries, he introduces a long string of similies. During this the battle is supposed to continue; and thus the time necessary for the action is gained in our imaginations; and a degree of probability produced, which contributes to the temporary deception or reverie of the reader.

But the similies of Homer have another agreeable characteristic; they do not quadrate, or go upon all fours (as it is called), like the more formal similies of some modern writers; any one resembling feature seems to be with him a sufficient excuse for the introduction of this kind of digression; he then proceeds to deliver some agreeable poetry on this new subject, and thus converts every simile into a kind of short episode.

B. Then a simile should not very accurately resemble the subject?

P. No; it would then become a philosophical analogy, it would be ratiocination instead of poetry: it need only so far resemble the subject, as poetry itself ought to resemble nature. It should have so much sublimity, beauty, or novelty, as to interest the reader; and should be expressed in picturesque language, so as to bring the scenery before his eye; and should lastly bear so much verisimilitude as not to awaken him by the violence of improbability or incongruity.

The occasion for each poem is a scientifically-framed fact – biological details about a plant species. (Or, in volume 1, facts about chemistry, or geology, or whatever is thought to be scientifically relevant to plant biology.) But not SF, not thought experiments. A funny sense of how to choreograph a fight scene. Let’s read on.

B. May not the reverie of the reader be dissipated or disturbed by disagreeable images being presented to his imagination, as well as by improbable or incongruous ones?

P. Certainly; he will endeavour to rouse himself from a disagreeable reverie, as from the night-mare. And from this may be discovered the line of boundary between the Tragic and the Horrid: which line, however, will veer a little this way or that, according to the prevailing manners of the age or country, and the peculiar associations of ideas, or idiosyncracy of mind, of individuals. For instance, if an artist should represent the death of an officer in battle, by shewing a little blood on the bosom of his shirt, as if a bullet had there penetrated, the dying figure would affect the beholder with pity; and if fortitude was at the same time expressed in his countenance, admiration would be added to our pity. On the contrary, if the artist should chuse to represent his thigh as shot away by a cannon ball, and should exhibit the bleeding flesh and shattered bone of the stump, the picture would introduce into our minds ideas from a butcher’s shop, or a surgeon’s operation-room, and we should turn from it with disgust. So if characters were brought upon the stage with their limbs disjointed by torturing instruments, and the floor covered with clotted blood and scattered brains, our theatric reverie would be destroyed by disgust, and we should leave the play-house with detestation.

The Painters have been more guilty in this respect than the Poets; the cruelty of Apollo in flaying Marcias alive is a favourite subject with the antient artists: and the tortures of expiring martyrs have disgraced the modern ones. It requires little genius to exhibit the muscles in convulsive action either by the pencil or the chissel, because the interstices are deep, and the lines strongly defined: but those tender gradations of muscular action, which constitute the graceful attitudes of the body, are difficult to conceive or to execute, except by a master of nice discernment and cultivated taste.

B. By what definition would you distinguish the Horrid from the Tragic?

P. I suppose the latter consists of Distress attended with Pity, which is said to be allied to Love, the most agreeable of all our passions; and the former in Distress, accompanied with Disgust, which is allied to Hate, and is one of our most disagreeable sensations. Hence, when horrid scenes of cruelty are represented in pictures, we wish to disbelieve their existence, and voluntarily exert ourselves to escape from the deception: whereas the bitter cup of true Tragedy is mingled with some sweet consolatory drops, which endear our tears, and we continue to contemplate the interesting delusion with a delight which it is not easy to explain.

B. Has not this been explained by Lucretius, where he describes a shipwreck; and says, the Spectators receive pleasure from feeling themselves safe on land? and by Akenside, in his beautiful poem on the Pleasures of Imagination, who ascribes it to our finding objects for the due exertion of our passions?

P. We must not confound our sensations at the contemplation of real misery with those which we experience at the scenical representations of tragedy. The spectators of a shipwreck may be attracted by the dignity and novelty of the object; and from these may be said to receive pleasure; but not from the distress of the sufferers. An ingenious writer, who has criticised this dialogue in the English Review for August, 1789, adds, that one great source of our pleasure from scenical distress arises from our, at the same time, generally contemplating one of the noblest objects of nature, that of Virtue triumphant over every difficulty and oppression, or supporting its votary under every suffering: or, where this does not occur, that our minds are relieved by the justice of some signal punishment awaiting the delinquent. But, besides this, at the exhibition of a good tragedy, we are not only amused by the dignity, and novelty, and beauty, of the objects before us; but, if any distressful circumstances occur too forcible for our sensibility, we can voluntarily exert ourselves, and recollect, that the scenery is not real: and thus not only the pain, which we had received from the apparent distress, is lessened, but a new source of pleasure is opened to us, similar to that which we frequently have felt on awaking from a distressful dream; we are glad that it is not true. We are at the same time unwilling to relinquish the pleasure which we receive from the other interesting circumstances of the drama; and on that account quickly permit ourselves to relapse into the delusion; and thus alternately believe and disbelieve, almost every moment, the existence of the objects represented before us.

Darwin, Erasmus. The Botanic Garden. Part II. Containing the Loves of the Plants. a Poem. With Philosophical Notes. (Kindle Locations 1146-1192). Kindle Edition.

One more note. In earlier section the subject of monsters is more directly addressed. Also, bold violations of known facts of time, space and existence.

And Shakespear, who excells in all these together, so far captivates the spectator, as to make him unmindful of every kind of violation of Time, Place, or Existence. As at the first appearance of the Ghost of Hamlet, “his ear must be dull as the fat weed, which roots itself on Lethe’s brink,” who can attend to the improbablity of the exhibition. So in many scenes of the Tempest we perpetually believe the action passing before our eyes, and relapse with somewhat of distaste into common life at the intervals of the representation.

B. I suppose a poet of less ability would find such great machinery difficult and cumbersome to manage?

P. Just so, we should be mocked at the apparent improbabilities. As in the gardens of a Scicilian nobleman, described in Mr. Brydone’s and in Mr. Swinburn’s travels, there are said to be six hundred statues of imaginary monsters, which so disgust the spectators, that the state had once a serious design of destroying them; and yet the very improbable monsters in Ovid’s Metamorphoses have entertained the world for many centuries.

B. The monsters in your Botanic Garden, I hope, are of the latter kind?

P. The candid reader must determine.

Darwin, Erasmus. The Botanic Garden. Part II. Containing the Loves of the Plants. a Poem. With Philosophical Notes. (Kindle Locations 773-781). Kindle Edition.

Two green thumbs up!

Here’s a soundtrack you can play in the background. Just put it on repeat.

{ 9 comments }

Christian Hendriks 02.24.18 at 6:40 pm

Fifty Shades of Green indeed! How this poem is not more widely appreciated I will never know.

John Holbo 02.24.18 at 10:55 pm

Whew! Tough crowd! Thanks, Christian.

steven t johnson 02.24.18 at 11:50 pm

In some year to come there may be a tell-all book that reveals the horror of poetry read at helpless children.

As to Charles Darwin’s advice on poetry, I am reminded of the story from T.P. Gore (as retold by his grandson,) that once, when riding with William Jennings Bryan, Bryan began to regale the Senator with the secrets of his, Bryan’s, political triumphs. The poor boy was disappointed to learn that Gore never quite heard the revelations, because of the question thundering in his ears: “What success?”

John Holbo 02.25.18 at 12:28 am

“In some year to come there may be a tell-all book that reveals the horror of poetry read at helpless children.”

In my defense, I also force them to read Jack Kirby comics with me.

ph 02.25.18 at 1:04 am

Erasmus Darwin is wonderful, but given your interest in illustration, you might wish to plunge deeper into the Birmingham Lunar Society, which ties in nicely with ceramics as a media, Banks’ illustrations for Captain Cook, Dufour’s Panorama on the same theme, and Blake.

The fifty shades of green! Wonderful!

monboddo 02.25.18 at 3:16 pm

Following up ph, if you haven’t read it yet check out Jenny Uglow, The Lunar Men, which centers on Erasmus Darwin. A really wonderful book.

John Holbo 02.25.18 at 3:29 pm

I haven’t read The Lunar Men. Last year I enjoyed Richard Holmes, “The Age of Wonder”, which had a bit about Darwin.

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/07/19/books/review/Benfey-t.html

John Holbo 02.25.18 at 4:10 pm

It’s weird the way Rod Dreher is so consistently on the same themes that I’m on.

http://www.theamericanconservative.com/dreher/keeping-a-chaste-garden/

David Duffy 02.27.18 at 11:54 am

https://www.worldcat.org/title/amazing-dr-darwin/oclc/52421322

is not too bad. I forget how much poetry is quoted.

Comments on this entry are closed.