My blogging is about two things: (1) the radical changes wrought by modern communication technology; and (2) the inability of the epistemic technologies of the written word to understand point (1).

I find this dialectical tension to be generative, but I can see how readers looking for answers might find it unsatisfying.

A recent paper in Nature, titled “Online images amplify gender bias,” makes the point in a more familiar format. Consider the first full clause of the first sentence of the abstract:

“Each year, people spend less time reading and more time viewing images”

BOOM. Footnoted: “Time spent reading. American Academy of the Arts and Sciences https://www.amacad.org/humanities-indicators/public-life/time-spent-reading (2019).”

I’ve frequently claimed that the age of reading and writing are over, with varying forms of evidence ranging from the political, the phenomenological and the Pew Research Center. I don’t think I’ve ever convinced anyone — some people (typically young, or frequently in contact with young people) already feel it to be true, and the rest won’t change their mind after reading a blog post. This is the contradiction of points (1) and (2). And yet Guilbeault et al (2024) establishes the relevant claim as a social scientific fact of the highest order.

How is this done? The introductory section of a social science paper in Nature is an odd medium. The argumentation has to range from the expansive to the specific, and the specificity has to cover a variety of spaces within the expansive argument — all exhaustively footnoted.

If you squint, this procedure becomes absurd. The clause in the abstract becomes “the time they spend producing and viewing images continues to rise[2,4]” in the body of the text.

Footnote 2 refers to a CS paper from 2013. Footnote 4, to a technical report from something called Bond Capital, in 2019.

Is this, in fact, evidence for the claim that “the time Americans spend producing and viewing images continues to rise”? What if this paper were to have been published in 2026? 2030?

And how does the fact that the main data analyzed in this paper were collected in August 2020 change things?

Of course, if you accept my premise (2), the literal content of the text doesn’t matter. The paper is a beautiful example of the contradiction inherent in techno-logos: we spend more time creating and consuming images, and less time producing and consuming texts. The evidence for this, recursively, does not reside in the text but in the images.

In the Flusserian framework, these are technical images. Images in fact predate texts; texts were invented because we stopped believing in images and we needed texts to explain those images. But the images in the pdf are not traditional images. Both the images under study and the statistical curves produced by the authors are technical images. These technical images are a cause and consequence of the fact that we no longer believe in text, and that we have invented technical images to explain those texts.

But let’s stay concrete! Guilbeault et al (2024) was published in Nature; what would the response be to me writing on my blog that:

“The time Americans spend producing and viewing images continues to rise. How do we know this? Zhang & Rui (2013) find that in the year 2012 there were billions of image searches conducted by Google, but in 2008, there were only a few thousand.”

The amount of evidence contained in the text is obviously insufficient to the claim — even if the information in the text is identical in the blog post and the Nature paper. The reason we believe the text in the Nature paper is because of the technical images in the pdf — these images point not to the world but to data, the true repository of knowledge today.

It bears mentioning that gender bias, the nominal focus of the paper, is a complete red herring. Obviously the argument is more compelling with an empirical demonstration, and it makes sense that the example would be something that people care about, that directly impacts their lives. But I fear that the focus on this issue obscures the argument itself.

The important part of this paper is the formal, large-scale demonstration that the mediums of text and image have different information-theoretic properties. We can try to demonstrate this empirically through small-scale experiments—indeed, I have done just this—but these demonstrations are always with respect to a given outcome, and have somehow not been convincingly synthesized. Alternatively, we can try phenomenology, to get people to experience these different mediums and reflect on this experiencing, to just THINK about what texts and images do—but that’s not scientific (Naturetific? Haha. I’m not envious at all.)

Or how about using language seriously? The claim here is that images provide more context than does text. That is, there is more extra-textual information in images than in text. What would it mean for this to be false? We literally can’t even think it false without linguistic contortion.

Another problem with the focus on the empirical case of gender discrimination is that the specifics of this case might change, but that our fundamental conclusion should not change. For example, the primary source of data for both the observational and experimental analysis is Google.

And Google is currently paying a whole lot of attention to the relationship between text, image and the representation of identity. There’s essentially zero chance you’re reading this without having heard about last week’s Gemini controversy, but just in case.

The point of this controversy is that images convey contextual information that is not present in text. This is not a problem that can be solved with RLHF fine-tuning or changing the composition of the training set; it’s a communicological fact.

It would not be (that) difficult for Google to reverse-engineer the specific analyses conducted in the Nature paper; the distribution of races and genders demonstrated for each occupation could be made to statistically match those in the Census, for example. Would this lead us to change our inference, to instead conclude that images and text contain the same amount of contextual information? No, of course not.

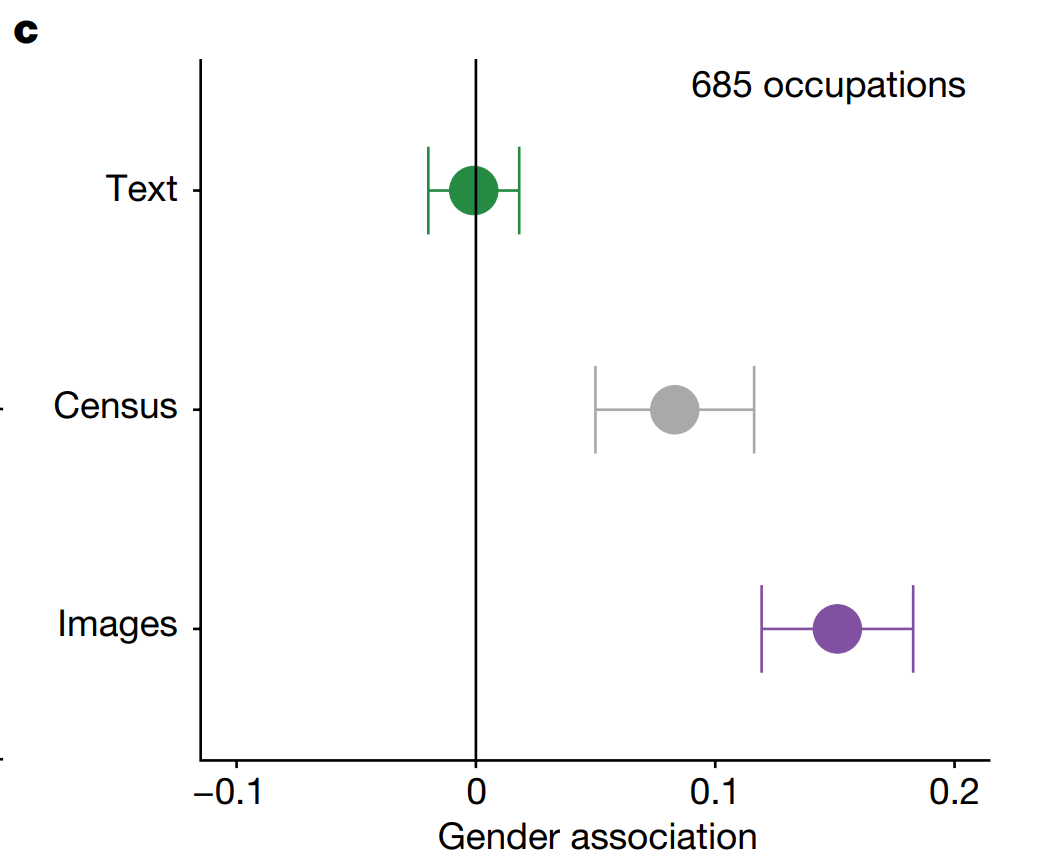

Returning to the paper, let’s ponder how Figure 2 shows that the Census has more “bias” in terms of gendered occupations than does the collection of texts. What on earth does this mean?

It means that our conception of “bias” is based on deviation from the textual, mathematical, linear, logical. This medium of communication and the associated habits of mind are very good at handling bias. But there are drawbacks. This medium is poorly equipped to communicate scale, change, and variation.

Images then necessarily introduce bias. A single image of a “philosopher” will necessarily be biased compared to the single word “philosopher.” One way in which it might be biased is gender; the word philosopher is not gendered, but most realistic images of people are gendered — not essentially or transcendently, but in practice gender is a pretty big part of self-presentation. But another way it might be biased is temporally. The word “philosopher” transcends time, but any realistic image of a philosopher would place them in time. The image would necessarily be biased compared to the word because images are better at conveying variety than at avoiding bias.

Here it become essential to understand what Flusser means by technical images as distinct from traditional images. These images “produced” by Google search or produced by Google Gemini are not images of the world; they are images of DATA. As are the images like Figure 2c above. These technical images are thus better than texts at conveying scope — and if extended to the third or fourth dimension, can be used to effectively convey dynamism as well. But just like traditional images, they are necessarily biased compared to text.

My hope, here, is to forestall a cottage industry of extending Guilbeault et al (2024) to every conceivable dimension of human communication. It is of course valuable to audit any given algorithm that has power to make decisions at societal scale — indeed I think that we are obligated to do so, and to generate time series data to see how these specific important algorithms are behaving over time — but the more fundamental point is that different modalities (“codes,” in Flusser’s framework) convey different kinds and amounts of information.

Simply by thinking about what these modalities do and tracking their empirical rise and fall in different areas of human endeavor, we can develop a much more robust understanding what information technology is doing to us — and we can decide if we’d rather it do something else.

{ 27 comments }

MisterMr 02.29.24 at 6:22 pm

“but any realistic image of a philosopher would place them in time. The image would necessarily be biased compared to the word because images are better at conveying variety than at avoiding bias.”

The text (word) does represent an abstract concept, whereas the image (say, a picture of Socrates) represents an individual who is a famou example of the general concept, but also will have singular characteristics.

But there is the question if the ideas in our head are more similar to “words” or to “images”: some research in cognitive sciences seems to push towards the concept of “prototypes”, that is when I hear “philosopher” my brain will not get an abstract definition but will pop out some famous philosophers, that I’ll then use as a “central point” of my definition of “philosopher”.

But then I don’t know how the brain works with abstract concepts like “love”.

John Q 02.29.24 at 7:06 pm

Where do sites like Facebook and TikTok fit into this classification? I’d say Facebook is basically text, with some illustrative images, and lame video attempts (Reels). Tiktok is (AFAICT), video only, but with more interaction than TV and some capacity for text comments.

At least as regards Facebook, the relatives I know who use it are interacting much more with text than they would have in the pre-Internet era.

hix 02.29.24 at 8:17 pm

Instagram is pictures, graphics with text and videos. The mix should vary depending on the user. Tik Tok should be just Video (resist, don’t observe yourself…). The (very) young typically were never using facebook. So in some sense, yes, definitely less plain text and more graphics/videos than some years ago.

But the very young still write/read WhatsApp, look up things on the Internet or similar. If we go pre internet in contrast, there were not all that many people that used to read the newspaper or magazines all that often, and even fewer books for leisure. So there is definitely also a shift to much more text on some timeframe. One of the links above only seems to measure how much time people spend reading novels, for the most part, which was never a relevant part of time spent reading for most people.

My guess would be, even the average amount of text people read at college increased a lot if we compare the no/little PowerPoint era with modern college, since often rather endless and very text heavy PowerPoints did not just crowd out reading textbooks but also much more limited blackboard /overhead projector teaching.

Alex SL 02.29.24 at 9:25 pm

I do not doubt that changing media and changing patterns of consuming media have an effect on people, but the statements in this post are generally of the type that has two possible interpretations, one correct but banal, the other potentially interesting but wrong.

I’ve frequently claimed that the age of reading and writing are over

What does this claim even mean? That we are reading less and watching more short videos than we did before the invention of the internet? Maybe so, but that is hardly the end of reading. That soon most people will be illiterate? That would be an interesting claim, but it is demonstrably, obviously false. My 14yo daughter reads, as do their classmates – among the birthday presents they give each other are regularly books. They read recipes to prepare food and are enrolled in a creative writing course. As for myself, I just read your post and am preparing a lengthy reply, which my father would have been unable to do at my age because blogs hadn’t been invented yet. You could just as well argue “the age of the car is over” because my city has built a single tram line to run in parallel to the daily traffic jam.

The reason we believe the text in the Nature paper is because of the technical images in the pdf — these images point not to the world but to data, the true repository of knowledge today.

The ‘image’ here is not an image in the sense most people understand it. Instead, it is a diagram / figure / graph that merely summarises the data, and the data are a form of text, in the format of a table, that a scientist would check directly if they wanted to ascertain that the claims made in the paper are correct.

More cynically, people believe the claim made in the paper not because of images but because they read (!) a post on social media that the claim was published in Nature. The mechanism of action at play here is the reputation of Nature, the belief that the journal has a stringent review process, which is best summarised as “several reviewers and editors have critically read (!) the text (!) of the paper”.

The claim here is that images provide more context than does text. That is, there is more extra-textual information in images than in text.

This again is true only in the circular sense that an image is an extra-textual piece of information, and text isn’t. But with regard to “more context”, the claim seems obviously wrong in any sense other than that form of circular reasoning.

A single image is extremely limited in what it can convey. In contrast, a text can have any information that is considered missing added to it through the process of… drum roll!… adding another sentence, and still remain a text. While an image has it perhaps easier invoking visceral emotions, a text can be much more precise and comprehensive in what it is intended to communicate. Imagine an image of a clear-felled forest on one side. Now imagine, on the other side, a text variously reading, “native trees were logged to produce low-value wood chips, in the process destroying one of the last three populations of a threatened bird species”, or “a former pine plantation will now be replaced with a nature reserve”, or “biosecurity officers had to cut down hundreds of trees infested with the shothole borer beetle in an attempt to stop its spread, as it has the potential to infest many native tree species across the continent”. It is precisely the case that text can provide context that the image cannot, by the very nature of the two media.

Images then necessarily introduce bias. A single image of a “philosopher” will necessarily be biased compared to the single word “philosopher.”

It is correct but also banal to point out that a single image of a single philosopher will show at most one gender. But it is false to call this bias, because a single photo in isolation cannot be used to demonstrate bias; only many images can. If I hire a single female technician the first time I have a single vacancy to fill, does that demonstrate misandry? No, that evidence in isolation would be laughed out of any conversation. For the same reason, writers (!) who want to demonstrate the biases of some generative AI have to post four or more images to make their case convincingly.

It could then be the case (although in reality it isn’t) that half of all images that exist of philosophers show women, or as many as proportional to the percentage of women among philosophers across history, or that this or the other is the case for the images produced by a given artist. Conversely, however, a single text in isolation can already clearly reveal the biases of its writer, because of the text’s complexity, information richness, and ability to illustrate to a competent reader the fallacies the writer falls prey to, whereas a single image in isolation is an extremely limited, flat, uninformative data point. So, here too, the opposite is actually the case.

JPL 02.29.24 at 11:11 pm

“Each year, people spend less time reading and more time viewing images”

Don’t forget that, for people who deal with texts, the term ‘text’ refers not just to written texts, but also to spoken texts; and that it can refer to not just the products of acts of language use, written, spoken, signed, etc.,), but to uses of other semiotic media, such as images (e.g., a non-verbal cartoon is a text). And images can be of verbal or non-verbal objects, visual or aural. So a text is the product of an individual act of creating significance. So, are you interested in the distinction between written verbal texts and visual non-verbal images (which are nevertheless understood in terms of the linguistic categories we use to understand the world in general)? Why exactly is this distinction so important? Is it because linguistic texts and their elements are always instances of the general categories of the linguistic system, which are brought to bear on the understanding of the world described, while non-verbal visual images have a necessary particularity (of this individual, not that one, and thus the inevitable bias) that the linguistic text needn’t have (e.g., generic reference)? As a result of this, the significance evoked by the linguistic text is potentially much richer, more resonant and more flexible than the non-verbal visual image. If the message is that, notwithstanding the trends, and although reading, as opposed to just looking at moving images, can be difficult, people should do more of it, I’m all in for that.

John Q 03.01.24 at 3:43 am

Here’s a link to a piece I wrote in 1995, predicting a coming Golden Age of Text. Broadly speaking, I think it’s correct though the advent of TikTok and YouTube may have weakened the case a bit.

https://johnquiggin.com/2020/08/19/so-last-millennium-repost-from-2004-linking-article-from-1995/

Something that really struck me in the linked American Academy study was the claim Americans still spend nearly three hours a day watching TV (I remember this same number being quoted decades ago) and only 28 minutes on recreational use of computers, including video games. Even allowing for the fact that TV now mostly means streaming rather than broadcast I find this pretty hard to believe.

John Q 03.01.24 at 3:46 am

The core argument from my 1995 piece

More fundamentally, text, unlike video, is an inherently nonlinear medium. A book or a newspaper can be skimmed or browsed, read in many different orders. But the nonlinearity of text has been constrained by the limitations of print. The academic article, with its array of footnotes, cross-references and citations is an elaborate attempt to surmount these problems. The World Wide Web and other innovations offer the potential of ‘hypertext’ (the term is due to computer visionary Ted Nelson, and the basic technology of the Web is called Hypertext Markup Language). While reading a page on, say, Nelson Mandela, you can jump to a description of the main tribal groupings in South Africa or on cultural changes in the townships. Then, if you are sufficiently disciplined you can return to the original page. Alternatively, you can wander off into pages on world music or anthropology (with sound and maybe video clips, but still organised around text).

Nothing like this is feasible with video. A string of loosely connected video clips makes, at best, a music video or an art film and, at worst, a mess. Admittedly, the best multimedia artworks can give the viewer a feeling of free movement while maintaining some degree of coherence. But the effort involved in constructing such works is immense, and the freedom of movement is illusory compared to that of hypertext.

J-D 03.01.24 at 9:03 am

I smile wryly.

William Berry 03.01.24 at 9:25 pm

What AlexSL, JPL, and John Q said. Pretty much straight down the line.

Alex SL 03.02.24 at 12:46 am

Images then necessarily introduce bias. A single image of a “philosopher” will necessarily be biased compared to the single word “philosopher.”

Belatedly, it also occurs to me that even this in isolation only makes sense from the narrow perspective of a non-gendered language. In many languages, even that single word would either identify the gender of the person or show a bias in folding a female philosopher under a male-gendered job title.

David in Tokyo 03.02.24 at 7:51 am

John Q writes: “Nothing like this is feasible with video. ”

Well, it is, actually. Somewhat, any way. Sort of.

My SO watches a lot of (Japanese) lefty political videos on YouTube here. (Japan’s currently in the midst of a brouhaha in which something like 90 of the LDP (the right-wing ruling party) have been caught with their grubby paws in the till, although, unfortunately, so far, neither the prosecutors nor the tax folks are going after them, yet.)

I’ll occassionally listen in, and, being political, content-dense, and linguistically hard (technical words are used in their exact meaning, so even if I know the words, I still need to think about what’s being said) I’ll need her to stop to allow me to catch up with what’s going on.

This works on YouTube. You can stop a video and think about it (or discuss it with the people you are watching it with) or even bop off to Wikipedia to check/verify something.

Watching the regular broadcast TV news (Japan still has major TV channels like the US used to), I noticed that you can’t do that. When someone says something worth thinking about, or a visual with useful data is presented on the screen, you can’t stop to look at the data and come up with an alternative analysis. The ads are somewhat useful for that. But they don’t appear when you need them and for the right amount of time.

Regarding how much people are reading, I have long had the impression that the amount of writing the Japanese produce and consume is of a similar order of magnitude to the amount that English speakers worldwide produce/consume: the Japanese really like reading and writing Japanese. I randomly picked one of the four monthly literary magazines to follow. At around 400 pages, it was slightly longer than the other three (roughly 350 pages at the time). Within a year, it had ballooned to over 600 pages every month. Of fine print. I’m lucky to read one or two articles a month, if that. And since some of the articles are serialized (and worth going back to), I can’t chuck them, and they’ve taken over my study. The damn things make Kirk’s tribbles look like a minor glitch. Sheesh.

Harry 03.02.24 at 2:48 pm

JQ: “At least as regards Facebook, the relatives I know who use it are interacting much more with text than they would have in the pre-Internet era”

I haven’t read the article John links to, but it predates the rise of the cell phone, so I doubt it mentions this: young people write messages to one another (and read messages from one another) far more than they used to. They’re generally short and uncomplicated, but it all adds up.

Tm 03.02.24 at 10:17 pm

I don’t know whether people read less or more than they used to. But I’m quite certain that in the internet era, far far more people write texts on a regular basis than used to be the case. Pre internet, very few people ever wrote more than an occasion postcard and perhaps a shopping list. Nowadays, very many, perhaps most, people regularly write text messages, emails, comments in all kinds of Internet forums and messaging services. Never before did so many people so frequently express themselves in writing.

John Q 03.03.24 at 2:10 am

Texting was just coming in around 1995. You had to do it with a numeric keypad, tapping multiple times to get the letter you want. For example, using the 1 key, you could do 1 for A, 11 for B and 111C, separated with * IIRC. So “cab” would be 111111. Young people could do this with their thumbs at amazing speed. I was already middle-aged and used email

Kaleberg 03.03.24 at 5:02 am

I think McLuhan blathered on about some of this. I had to read Understanding Media in high school for whatever that was worth. Decoding text makes the reader do a lot of work. Listening to audio provides voices, cadences, pauses and a host of other cues. A play gives even more instantiation, less work for the viewer, more work for the set designer, the casting director and so on. Video takes it even farther, the viewer doesn’t even get to choose what to look at: there is only one set of eyeballs.

McLuhan used the terms “hot” and “cool”. I think print and radio were hotter and television was cooler. Keeping hot and cool straight is possibly why people ignore him now.

I think email and texting have brought back written communication even when images are involved. What are memes but postcards with packaged images and a place to write “wish you were here”.

engels 03.03.24 at 12:24 pm

As Richard Seymour put it (in his inimitable way): we are all scripturient.

https://theindigopress.com/product/the-twittering-machine-paperback/

(Except for me, as 90% of my comments seem to vanish now: maybe this will be an exception.)

Richard Melvin 03.03.24 at 12:33 pm

Pretty relevant meta-point; text is really really bad and developing and expressing new ideas. The best case is to coin and have accepted a new word. Each year, there are lists of ’10 new words ‘, of which at least half are filler. So perhaps 3 or 4 people get to do this a year,

This is obviously completely inadequate to keep up with the complexity of modern society.

It’s why mathematicians use either formal symbols or diagrams. It’s pity that the modern web is amazingly bad at both. There is few tools that will accept, say, a graph of income distribution, but won’t accept a porn video.

Harry 03.03.24 at 6:43 pm

JQ — yes, they could (and still can). It seems to me that my two younger kids (neither of whom reads books, whereas I used to devour them — still do) probably wrote far more in their teens than I did (and I was an enthusiastic letter writer, at least in my later teens).

Am I right that texting was a sort of add-on feature that was included in mobile phones because it cost nothing, but the designers assumed that nobody would actually use it?

John Q 03.03.24 at 7:24 pm

I’m not sure what the designers thought, but it was a cheap add-on. The real surprise for me was when Twitter used the same add-on capability to reinvent microblogging.

@Richard Melvin: Your apparent claim that text can only express new ideas by inventing new words seems very strange to me. I’ve typed millions of words, none of which were new to the language. And I do think I’ve had some new ideas in there somewhere.

I’ve also had some new ideas that I’ve expressed in mathematical symbolism. But again, I didn’t invent any new symbols, I just used the old ones differently.

Mitchell Porter 03.03.24 at 7:27 pm

David in Tokyo – history repeats?

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1994_Japanese_electoral_reform#Money_politics

J, not that one 03.03.24 at 9:18 pm

On the pro-text side, watching videos with captions on seems to be pretty popular among the youngs, in part because of lots of poor quality videos, but not only that. Converting sound waves to text uses a certain amount of mental energy too.

J, not that one 03.03.24 at 9:20 pm

I worked for a company in the early-to-mid 90s that had the monopoly on devices that routed SMS through the system at a certain level. Almost all their customers at the time were in Asia, but there were a lot of them.

Lee Arnold 03.03.24 at 9:38 pm

I watch video lectures with captions on, sound off, at 2x speed. You can get through a one hour lecture in 30 minutes. An easy way to see the main points, the holes in arguments, and to avoid wasting too much tme in the vast swamp of mediocrity.

Trader Joe 03.04.24 at 1:52 pm

The rich irony of the fact that we are debating this on a blog medium which is nothing if not text that is both read by the writers and written by the readers.

I don’t know if its still taught this way – but journalism classes used to have the adage that all images require text, but text does not require images. The point being that even something banal we all recognize – say the White House – is likely to have a caption under it explaining why we are showing a picture of the White House.

When you think wholistically about images and videos they are almost always accompanied by actual text to explain their purpose or the conclusions one is being encouraged to draw. Indeed in the graphic in the OP about biases, if it weren’t for the text contained in the X and Y axes the image would we worthless. Is looking at the axes or the legend not reading? Is including them not writing?

There is a lot of interaction between words and pictures, its hard to isolate bias within in them. Seems more likely that its the interpretor that brings the bias.

KT2 03.04.24 at 10:29 pm

BOOM! Today, major news outlets are publishing artiles about the Jama Pediatric study “Screen Time and Parent-Child Talk During the Early Years” from this … “Telethon Kids Institute waded through the 7,000 hours of audio they found toddlers in the study were averaging three hours of screen time a day, and that lost learning quickly added up.” … “For the three-year-olds in our study, we showed that for one minute of screen time they were hearing seven fewer adult words, they were speaking five fewer words themselves and they were engaging in one less conversation each day,” senior research officer Mary Brushe said.”

The abc net au article ends with…”Dr Brushe and the team may develop responses to those unanswered questions with further research.”. May develop! Too late!

And technology has wroght, as McLuhan said; “The present is the enemy.” (1960?) Witness the speed at which images have been delivered over text. Taylor Swift fans in “Sydney bringing the average across the major providers to 15TB per concert.”… “Fans at one of Taylor Swift’s shows in Texas reportedly doubled Melbourne’s usage, reaching 28.9 TB in total traffic.”…”That’s the equivalent of 15,500 hours of video, lasting 1.7 years if it was played continuously.”.

Double for Texas concerts! Exceptional USA. Whoa. Carbon tax please.

Technology at present floods out much text. (See below for category errors). And yes…““Online images amplify gender bias,” … “Each year, people spend less time reading and more time viewing images”. Imagine GPT n+1 trained on 1.7yrs + 3.4yrs +++ continuos video of Tay Tay. Ephemera crap. Which if I were a kid today I’d probably by guilty of too. Image based global heating amplification. JQ, weren’t you going to write about ephemera?

By the time further research is done it will be TOO LATE. e/acc is backed by 16oz and Marc Adreseen (who lies in front of Congress), and backs and prozletizes every screen based technology which delivering a set of network effects and images producing a category error with, as Kevin Munger points out- “two things: (1) the radical changes wrought by modern communication technology; and (2) the inability of the epistemic technologies of the written word to understand point (1).

“I find this dialectical tension to be generative, but I can see how readers looking for answers might find it unsatisfying.”

I am unsatisfied. Kevin has a good point – text is not going to elucidate or convince via the written word the “radical changes wrought by modern communication technology”. Yet I find Kevin that your claim “that the age of reading and writing are over” is so absolute as to, which you decry of the refereces you quote, “… the focus on this issue obscures the argument itself.”, as shown by commenters decrying your strong and absolute claim.

But all I see here are category errors;

– text types: books / news / technical / blog / propaganda / handnwritten

– setting vs medium: If in echo chamber or church, speech crushes all text and imagery. Political rally attendee vs reading or viewing policital adverts

– graphs / visualisations / family pics / concert vision

… and on and on.

Supposedly, 5,000,000 words spoken by parent and heard by toddler by age 5 (÷(365×5) = 2,738 words per day

At 12 hrs / day = 228 words per hour) is optimal for brain development, IQ and prosocial behaviours. Because these words and in a different category to text, screentime, books etc. Like attendees at a church or political rally, the message is mind altering not mind maybe influencing vs noise factor vs attention vs surprise.

At conversational speech speed of 120-150 words per minute x 60 x 12 hrs we get 86,400-108,000 wpday. Of course we never speak or hear every minute of hour, yet kids now DO spend every minute and hour in screentime. Which is more cognitive and influencing? Category.

Screentime though is all absorbing image based medium and may or may not add to “…the more fundamental point is that different modalities (“codes,” in Flusser’s framework) convey different kinds and amounts of information.”, as KM says. (2nd last para.)

We had better work this out VERY QUICKLY, otherwise e/acc and Taylor Swiftees will drown us in imagery. And burn the planet down.

###

For the future see Dynamicland.

As to the future of of text, video, computer and communication see;

Dynamicland by Brett Victor et al

“Writing and print transformed humanity. Computing will have as great an effect. What will be the shape of this transformation?

“Will it lift all people, or widen the gap? Give people agency, or give them products to consume? Bring people together, or isolate them? Deepen people’s connection to their bodies, their hands, and the real world we all depend on? Or abstract human beings into pixels and database entries?

“The time to decide is now.”

…

“No screens, no devices. Just ordinary physical materials —

paper and clay, tokens and toy cars — brought to life by technology in the ceiling.” … “Every scrap of paper has the capabilities of a full computer,

while remaining a fully-functional scrap of paper.”

If in Oakland, knock on the door. I would.

dynamicland dot org

###

Today. 5th March 2024 “Screen time robbing toddlers of language-building interactions with parents, study finds” abc net au & NYT etc

“Screen Time and Parent-Child Talk During the Early Years” 2024 JAMA

“Screen Time and Parent-Child Talk During the Early Years”

1 day ago – In the adjusted models, the results show that increases in screen time were associated with decreases in parent-child talk …”

jamapediatrics › fullarticle › 2815514

KT2 03.04.24 at 10:36 pm

And dangerous times past and present.

News as propaganda creates toxic text and images.

RLHF is imo absolutely necessaty.

“Just Fancy That

An analysis of infographic propaganda in The Daily Express, 1956–1959

Abstract

“This research finds that the emergence of infographics as a regular phenomenon in UK news can be traced back to The Daily Express of the mid-1950s. These “Expressographs” were often used not as a means of conveying data accurately and objectively, but in order to propagate the paper’s editorial line, and to further Lord Beaverbook’s political interests. A series of editorial narratives are established via the literature on The Daily Express, and its proprietor Lord Beaverbrook. These narratives are used as a framework to analyse statistical infographics published in The Daily Express between January 1956 and October 1959, by means of a combined content analysis and structural semiotic analysis. Best practice, as espoused in the information design literature, is used to identify misleading graphical methods in the sample, which were then analysed in the context of the editorial narratives identified. This study finds that infographics in UK news were the product of a lavishly financed organisation whose key decision-makers were deeply concerned with the impact of the visual in news. The purpose of these infographics was to perpetuate their employer’s idiosyncratic view of how the world should be. Occupational norms and practices may account for some of the biases identified, but cannot account for the breadth, range and consistency of bias found across the sample, which constitutes an example of mid-twentieth-century propaganda.”

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/figure/10.1080/1461670X.2013.872415?scroll=top&needAccess=true

David in Tokyo 03.05.24 at 7:09 am

Mitchell Porter asks about history repeating.

Well, sort of repeats. The details are different. This time it’s the rank and file folks who have their hands in the till. Dunno if it’ll last to the next election, but LDP popularity is at an all time low.

Like John Q says: the idea that text is problematic for new ideas requires completely missing 20th century linguistics. To say nothing of philosophy, literature, and science in general.

Comments on this entry are closed.