Every time I start writing something about The Situation, it seems pointless. Both the media environment and the world itself seem to be spinning out of control. The bubble of Boomer Realism has been popped. The weirdness which has been bubbling since 2008 has flooded the territory; old maps seem worse than useless. I’ve got nothing better than aphorisms to offer to understand the present.

Thankfully, my job interacting with students and colleagues forces me to be a bit more concrete. I’m very excited about the re-launch of the APSA Experiments Section Newsletter, which I’m editing along with Krissy Lunz Trujillo — check it out here.

But mostly today I want to talk about the graduate seminar I just finished teaching, about Media, Social Media and Politics. The syllabus is here. To summarize what we spent the most time talking about in class, I’ll quote a sentence from Green et al (2025): “The online information ecosystem in the early twenty-first century is characterized by unbundling and abundance.”

I taught a similar class four years ago, and let me tell you, the academic literature has not changed nearly as fast as the underlying pheonomena have. The lag is getting worse. But even if it’s slow, scientific progress has been made. In my view, the most important results come not from fancy causal inference but from large-scale quantitative description; this should not be surprising coming from the editor of the Journal of Quantiative Description: Digital Media.

This evidence has caused me to update my beliefs about one of the central research questions in this field. Social media is an echo chamber.

To be clear: I still think that the term “echo chamber” is more confusing than helpful. So let’s be more precise. The question at issue is whether media diets on social media tend to be less diverse than media diets in other forms. A person is in an “echo chamber” if a high percentage of that person’s media diet comes from one side of the political spectrum.

According to this definition, social media was consistently found not to be an echo chamber — there was more cross-cutting exposure on social media, or at least exposure to centrist political media, than the average media diet consisting of cable tv or newspapers.

I’ve written about this several times, forcefully echoing the conclusion in this Knight foundation white paper that “public debate about news consumption has become trapped in an echo chamber about echo chambers that resists corrections from more rigorous evidence.” Conceptually, it makes sense: what “algorithm” could be more biased than the Fox News cable channel algorithm, which shows 100% conservative vidoes and 0% liberal or centrist videos? And the empirical evidence was overwhelming — media diets on social media tended to overlap strongly, with the exception of maybe 10% of the population that opted to consume only left or right-leaning content.

Two recent papers call this empirical consensus into question. The first, Gonzalez-Bailon et al (2023), I’ve discussed before as part of the Meta2020 collaboration — although I (like everyone else) gave it less attention than the flashier experiments about the effect of eg switching to a chronological feed. This paper has unique access to a huge amount of proprietary Facebook data and demonstrates two crucial points. First, “the algorithm” can only explain a moderate amount of bias in media diets — a larger share of the of the bias comes from choices by media consumers. You can see this by reading these two graphs from bottom to top.

But the bigger finding comes from comparing panels E and F. Almost all of the research estimating this question used data aggregated at the domain level, as in panel E. This means that each domain (New York Times, Wall Street Journal, Infowars etc) gets assigned an ideological leaning. And the findings of this paper, at the domain level, replicates the recieved wisdom: there’s a cluster of diehard conservatives, but otherwise there’s a fairly healthy distribution of media diets across the spectrum.

The problem is that aggregating these ideological measures to the domain level misses crucial heterogeneity in the leaning of individual pieces of content, as panel F demonstrates. The curation problem is considerably worse than at the domain level, but most importantly, the healthy middle of the distrubtion disappears. The conservative-only cluster gets much larger, and a sizeable liberal-only cluster emerges. The topline finding of the paper is summarized as “asymmetric ideological segregation,” but I think the more important result is that a much larger percentage of Facebook users have highly skewed media diets.

This is an important result from a unique dataset, but it’s still just one platform at one point in time. The recent publication by Green et al (2025) about “Curation Bubbles” really moves the needle both empirically and conceptually.

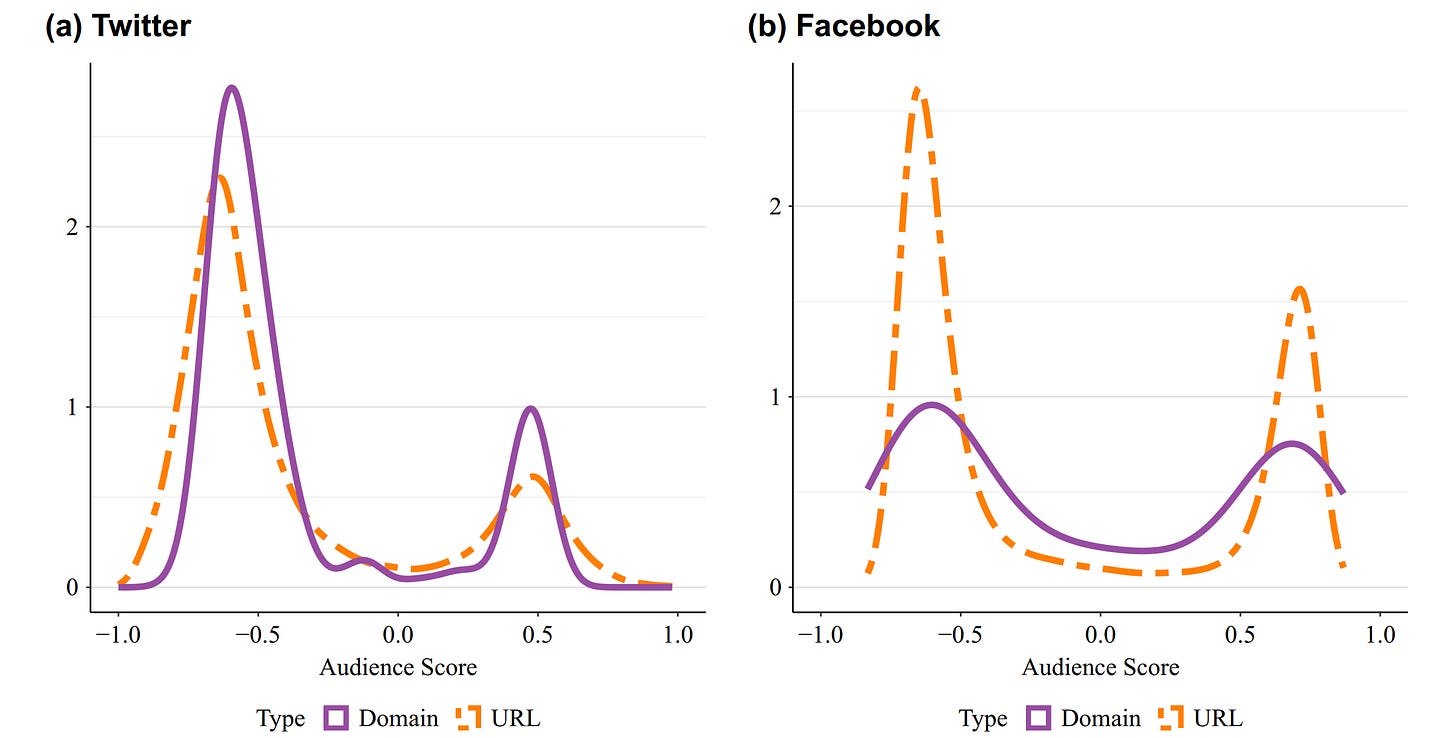

Using two different data collection approaches, they find the same result about domain-level vs URL-level polariztion on both Facebook and Twitter.

The Facebook result in panel B is almost identical to the result above — the healthy middle falls out when we switch from domain- to URL-level analysis, and the two poles emerge. On Twitter the result is different. Here in panel A there’s no healthy middle even for the domain-level analysis, but switching to URLs moves the distribution even further towards the tails. That is, the clusters still exist — but they miss extreme ideological polarization on both the left and the right.

The case of the Wall Street Journal makes the methodological problem clear. The WSJ is usually classified as centrist or center-right, even as researchers often acknowledge that the editorial page tends to lean strongly to the right. By averaging social media consumption or sharing data across the entire domain, the WSJ shows up in the middle. However, Green et al break the domain down by URL — and find that only a tiny percentage of stories are actually centrist.

Some of the URLs circulate only among the right, others only among the left! There’s more ideological segregation within the WSJ than most earlier research finds among all of social media.

The empirical advance from these two papers came by focusing on the URL rather than domain level when estimating the ideology of digital media. But the conceptual problem is deeper. Deep in the limbic system of quantiative Political Science is the idea of ideological scaling. Specifically, unidimensional ideological scaling based on elite behavior. Even more specifically, from DW-NOMINATE scores derived from roll call votes by Members of Congress.

The intuitions based on a conception of ideology derived from DW-NOMINATE cause problems when applied out of domain. This is a context where institutions mandate that there are only two parties — and where the action space is up-or-down votes on bills that make it out of committee.

“Ideology” in Congressional voting is tightly bundled (by institutions) and decidedly non-abundant. It’s hard to imagine a worse reference point to understand how “ideology” functions online, a space characterized by unbundling and abundance. Conceptually, it’s essential that we move beyond a unidimensional of ideology to model online politics. Indeed, I believe that one of the most important political effects of the internet has been the emergence of alternative political canons that raise the dimensionality of the space.

Green et al (2025) connect their empirical results to a theoretical advance that better reflects how social media actually operates:

Information on social media is characterized by networked curation processes in which users select other users from whom to receive information, and those users in turn share information that promotes their identities and interests. We argue this allows for partisan “curation bubbles” of users who share and consume content with consistent appeal drawn from a variety of sources. Yet, research concerning the extent of filter bubbles, echo chambers, or other forms of politically segregated information consumption typically conceptualizes information’s partisan valence at the source level as opposed to the story level.

I wrote last year that “Social media is social, is my theoretical mantra.” And I’m happy to see this mantra repeated by Green et al in the august pages of the APSR: “Social media is, at its core, social, allowing users to use information to perform their identities and advance their interests in the context of democratic participation.” The idea that what makes social media unique is “the algorithm” is just ridiculous.

So let’s return to the idea of unbundling and abundance. The abundance part is simple but always bears repeating: the amount of media produced in the 21st is incomprehnsibly larger than in the 20th century. To the extent that more “extreme” media is being consumed, a first-order cause is that more “extreme” media is being produced.

“Unbundling” and subsequent “rebundling” are the central mechanisms distinguishing the 21st century media environment from the 20th. Researchers focused on media economics have long appreciated this point; take Matt Hindman’s fantastic book The Internet Trap, for example, or several articles by Ben Thompson on his Stratechery blog. The ability to bundle content together is a powerful economic tool, once held by media firms and then usurped by tech platforms.

Green et al’s concept of “curation bubbles” highlights the fact that users also have considerably more ability to bundle and unbundle than they did in the 20th century. On both the production and consumption side, social media users have more agency to curate the content bundle that they prefer. The bundling process is iterative and cumulative: the actions they take in cultivating networks or audiences persist into later periods.

Of course, very few users take full advantage of this curation. This is because the platforms are playing a double game, trying to extract as much information from users as possible while retaining bundling agency themselves, as both elements contribut to their advertising-driven bottom line. Over the past five-ish years, social media has become much more algorithmic, both because of the rise of TikTok and the influence of TikTok on other platforms.

This leads me to the biggest problem with these two papers, a problem which readers will recognize as a hobby horse of mine. They’re already out of date! The data from Gonzalez-Bailon et al (2023) is from 2020, and the data from Green et al (2025) goes up to February 2021 (for the Facebook data) and December 2018, for the Twitter data. This is a huge temporal validity issue!

We have now, five years after the decade ended, developed a coherent conceptual and empirical grasp of how social media politics operated in the 2010s. Unfortunately, I don’t think social science can plausibly expect to do much better; the problems are just too difficult. I still think that what we do is valuable even if we can’t be up to date. But I also don’t think that politicians and democratic citizens can afford to wait for us to develop a settled understanding of social media before taking actions to regulate it. The question, as ever, is how to build the society we want.

{ 3 comments }

Nathan TeBlunthuis 03.14.25 at 2:50 am

Thanks for the write-up Kevin! In some ways it’s hopeful to feel a sense of clarity looking at the url-level findings. An inch of empirical progress in the field.

Jonathan Hallam 03.15.25 at 11:03 am

Is there any information on sub-distributor level data in legacy media… eg, studies identifying which articles in a particular newspaper were read by liberl/Conservative readers, or skybox-level tracking information on particular stories within news programs?

Or do we think that once you’ve bought a paper you read all of it, and that once you’ve put the news on you tolerate a story with an ideological frame you disagree with…(?)

John Q 03.15.25 at 7:55 pm

My shorter version of “curation bubbles”: People are misinformed because they want to be

Comments on this entry are closed.