Unemployed, I spent a week in April digging a small pond in our back yard. At the time, it was a distraction. Now it is… actually, a different sort of distraction.

Because although it’s not a very big pond — about 3 meters by 2, maximum depth about 70 cm — it has very quickly and suddenly filled up with life. The first water skater appeared literally on day one. Now there are about a dozen of them. We’ve also picked up water beetles, a couple of aquatic snails, some little swimming shrimp-like things, and several of these guys:

Ichthyosaura alpestris, “fish-lizard of the Alps”, aka the Alpine Newt.

But how did they get there?

In brief: your Alpine Newt will spend nine months of the year on land, slithering around in the leaf mold in forests and brushy meadows, gobbling up insects and other small invertebrates. But in early summer, they look for water, because they need water to breed. So there were probably some around in our yard and in the vacant lots nearby. And when suddenly we added our little pond to the local ecosystem, well, we basically set up a singles bar for newts.

They’re cool little guys. They’re about 10 cm or 4 inches long — about as long as your middle finger, say — and they mostly hang out at the bottom of the pond. But every 5 or 10 minutes they’ll swim up to the surface in a very leisurely sort of way, take a gulp of air, and then swim back down. There are at least four of them, but sometimes we’ll only see one, or none. We assume that’s because they’re out hunting, returning to the pond to rest.

(And to get it on, presumably. But apparently they only do that around dawn. Dawn in northern Bavaria in May comes at 5 AM. There are things that will get me out of bed at 5 AM, but hoping to catch newts in flagrante doesn’t quite qualify.)

Anyway. Remember my post a couple of months back about the blue-ringed octopus? Well, it turns out the newt shares a trick with that pretty little mollusc: they both have tetrodotoxin. Unlike the lovely but lethal blue-ring, the newt only produces a modest amount. If you ate one, your mouth would go numb, and then you’d probably have nausea, maybe muscle spasms, and perhaps some difficulty breathing for a while, but you wouldn’t die. A smaller predator like a bird or a raccoon would have it worse, but still probably wouldn’t die. But it would (presumably) be a nasty enough experience that the predator wouldn’t much care to repeat it.

Which is why the newts look the way they do. Their backs and sides are a mottled grey-green, great natural camouflage. But their throats and bellies are bright orange. So camouflage is their first line of defense; they’re not toxic enough to advertise openly, like an Amazonian poison frog or such. But if threatened or cornered, they may raise their heads to display their bright orange undersides: warning! I taste nasty and will make you sick!

— And how does the newt get the tetrodotoxin? This is one of those things where you can’t just read wikipedia. You have to search for papers, like people did in medieval times.

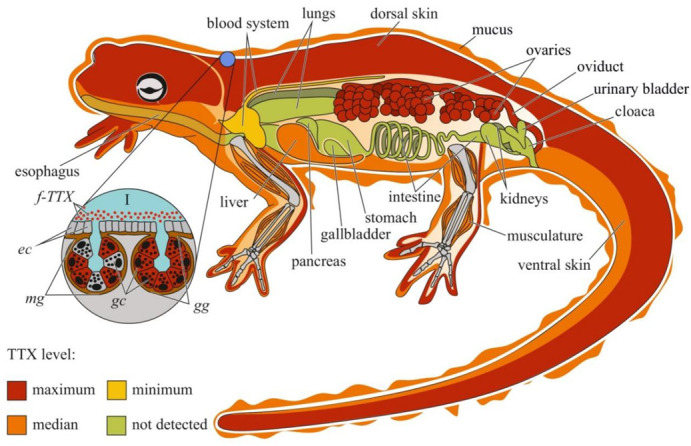

[Melnikova and Magarlinov, ibid. The green bits are probably safe to eat.]

Turns out the newt, like the octopus, gets its tetrodotoxin from symbiotic bacteria. They live mostly in glands in the newt’s skin — that’s the cutout at lower left — but also in the ovaries, which is why the ovaries are bright red. Makes sense, right? The newt wants to pass the bacteria on to its children, and the bacteria want to be passed.

What’s interesting is that the newt is toxic, but it’s not very toxic. Presumably that’s because supporting all these bacteria carries a metabolic cost. So, becoming more toxic still — evolving into a newt version of the blue-ringed octopus — isn’t worth the trouble.

(There are a couple of newt species in North America that have done this, becoming much more toxic, to the point where they could seriously injure or kill an adult human. We think we know why, and it’s because of reasons that are beyond the scope of this short blog post. That said, American readers please attend: don’t lick newts.)

So, Elon Musk destroys USAID -> I’m unemployed, dig a pond -> newts hooking up -> tetrodotoxin. And that’s our set of unexpected connections for this week.

{ 12 comments }

oldster 05.31.25 at 7:46 pm

Has completing excavations been a theme in your life, Doug?

Dumas 06.01.25 at 5:39 am

Thank you for this . Do they have any predators?

Cw 06.01.25 at 5:47 am

Thanks for this fascinating post. And thanks also for your work with USAID.

Chris Armstrong 06.01.25 at 7:52 am

@2 Herons eat newts (from the water), as do foxes, badgers etc (from the land)

Mostly lurker 06.02.25 at 12:31 am

There was a story in a book I read about California’s oak woodlands about a trio of hunters that, back in the 50’s, were found dead at their camp with no sign of foul play. It turned out they hadn’t noticed that a California Newt had slipped into their coffee pot overnight. They brewed up coffee and poisoned themselves with tetrodotoxin. I don’t know how toxic California Newts are, because boiling them probably brings out all the toxin they possess.

Peter T 06.02.25 at 12:42 am

Have you figured out which newts are just newts and which are witch-victims?

engels 06.03.25 at 6:57 pm

I spent a week in April digging a small pond

Living up to your forename!

J-D 06.04.25 at 3:07 am

The California newt is one of four species in the genus Taricha, members of which are known to produce very high levels of tetrodotoxin. Generally it is the rough-skinned newt which is the most toxic of the four species, although populations on Vancouver Island produce little or no tetrodotoxin.

Jaspersmom 06.04.25 at 4:02 am

What a fabulous photo and interesting post!

Thank you

Neville Morley 06.04.25 at 6:03 pm

Digging a pond (actually, digging a new pond, as the old one was too small and in the wrong place) was my big project in lockdown back in 2020. It was likewise rapidly colonised by wildlife: newts, frogs, beetles and dragonflies in particular – twenty-seven emperor dragonflies so far this year have emerged from the mud and flown off. I’m sorry that your newts are so shy; British common newts have no shame and do their courting in broad daylight, and the tail-wiggling really is fascinating to watch.

William S Berry 06.04.25 at 8:38 pm

I have a wooded back yard/ garden with a nice little brook running across it (it comes down from a ridge just a bit north of my place).

I have bats, snakes, frogs*, lizards, even an owl (and a neighbor has a dog!). I also own a large stainless steel pasta pot that would work fine as a stovetop cauldron.

Alas, I have no newts. Everybody’s safe!

*Bullfrogs. When I open my bedroom window on a cool summer night I can go to sleep listening to their lusty songs of love.

Alan White 06.05.25 at 5:23 am

Please keep writing these excellent insights. I love them.

Comments on this entry are closed.