I’ve expanded my series on refuted economic doctrines to include an approach I think has been rendered largely obsolete by the global financial crisis (along with earlier developments). I’ll give the short version here, and point to a longer post at my blog, which might be better for more technical points.

[click to continue…]

From the category archives:

Economics/Finance

John’s post reminds me that I was giving some grief to Matt Welch about seasteaders and the more … conceptually novel side of libertarianism last week (Matt held his own).

This came up in an argument over Peter Leeson’s new book on the joys of eighteenth century piracy as an exercise in stateless government, and the recent excitement off the coast of Somalia. I suggested that Somalia looked like a libertarian paradise – no government, lots of guns etc – something that Matt certainly didn’t agree with personally. But what I didn’t know (until one of the bloggingheads commenters pointed it out) was that Peter Leeson himself has written an article arguing that “modern Somalia is teh awesome”:http://www.google.com/url?sa=t&source=web&ct=res&cd=1&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.peterleeson.com%2FBetter_Off_Stateless.pdf&ei=f1HvSY3bIt6HlAfM_tQp&usg=AFQjCNGG2u3zX0OOHBmfsJ00LJIiuI829Q (or, at least, a lot better than you might think). As he argues in a different, summary essay (linked to below):

Like all other choices, the choices we face in “selecting” governments are constrained. Unfortunately for most developing countries, the political choice set they face is far smaller than the political choice set more developed countries face. Historical features, such as clan tension, rampant corruption, territorial conflicts, and many others, which cannot be changed in the short run, severely restrict the kind of government countries like Somalia can reasonably expect to have if they have a government. Sadly, well-functioning, well-constrained governments like the ones we observe in the U.S. and western Europe are not part of this choice set. Ultra-predatory, corrupt, and abusive governments, however, are. And so is anarchy. As Somalia’s experience illustrates, for many LDCs with these limited options anarchy may very well be the best feasible choice.

I’ll leave the claim here to others who know African politics better than me (Chris Blattman, feel free to chime in) and merely note that these views presents an interesting question for the Princeton people charged with publicizing his book. On the one hand, piracy and Somalia are surely topical issues, but on the other, professor Leeson’s views on piracy and the benefits of Somalian political organization are likely to be unpopular with many people (his current proposed solution for the Somalian piracy problem, by the way, is to privatize the ocean).

I’ve started reading his book on piracy, which is an entertaining enough exercise, but one which I suspect is a bit fishy on the empirics. He clearly has his ideological druthers (see “here”:http://www.cato-unbound.org/2007/08/06/peter-t-leeson/anarchy-unbound-or-why-self-governance-works-better-than-you-think/ for his grand theory of why we don’t really need government), but then, so do we all. While I don’t find his claims for anarcho-libertarianism to be particularly convincing, I am probably not the target audience, and they have their place in the grand ideological debate. What I do find disconcerting though, is his obvious sweet tooth for efficiency arguments and just-so stories. History, when you look at it at all carefully, is much too messy to support any ideological explanation unequivocally. The book (and the academic articles that it draws upon) simply feel too neat to me, and don’t persuade me that he went into his research on these topics looking to be surprised by what he found (which I really think you should, any time you engage in empirical research). Others’ mileage may vary.

I’m lecturing on Hobbes this week. Since it is a first year lecture, I’m not going to get too deep into any of the controversies, but I will try to give the students a sense of who Hobbes was, why he remains important and how his ideas connect to other topics they may come across. I’ll probably say something about Hobbes’s time resembling ours as a period of acute religious conflict.

Suppose I were lecturing about Karl Marx: I’d do the same thing. I’d probably start by discussing some of the ideas in the _Manifesto_ about the revolutionary nature of the bourgeoisie, about their transformation of technology, social relations, and their creation of a global economy. Then I’d say something about Marx’s belief that, despite the appearance of freedom and equality, we live in a society where some people end up living off the toil of other people. How some people have little choice but to spend their whole lives working for the benefit of others, and how this compulsion stops them from living truly truly human lives. And then I’d talk about Marx’s belief that a capitalist society would eventually be replaced by a classless society run by all for the benefit of all. Naturally, I’d say something about the difficulties of that idea. I don’t think I’d go on about Pol Pot or Stalin, I don’t think I’d recycle the odd _bon mot_ by Paul Samuelson, I don’t think I’d dismiss Hegel out of hand, and I don’t think I’d contrast modes of production with Weberian modes of domination (unless I was confident, as I wouldn’t be, that my audience already had some sense of those concepts). It seems that Brad De Long “has different views to mine”:http://delong.typepad.com/sdj/2009/04/delong-understanding-marx-lecture-for-april-20-2009.html on how to explain Karl Marx to newbies. Each to their own, I suppose.

That’s it for my guest-blogging here at CT. Thanks once more for the invitation, and to those who read and/or commented on the posts. You can find me at Consider the Evidence.

The Labour Party returned to power in the U.K. in 1997 based in part on a pledge by Tony Blair and Gordon Brown not to raise taxes’ share of the British economy. In his 2008 presidential campaign, Barack Obama promised to reduce taxes for the bottom 95% of Americans. In both instances this commitment succeeded in insulating the progressive candidate from what had become the right’s most powerful electoral club: stoking fear of tax increases by the left.

But while it may be smart electoral politics, committing not to increase taxes’ share of GDP, as Blair did, or to lower taxes for most of the population, as Obama has done, makes it difficult for a government to make much headway in addressing income inequality. Obama has some leeway; the economic crisis has necessitated increases in government spending that can justifiably excuse some backtracking on his campaign pledge. Fully consistent with his promise, he should increase the tax rate on high-end incomes (beyond simply letting the Bush reductions expire). Two other progressive tax reforms are worth pursuing, though they would affect some in the bottom 95%. One is to reduce or end the homeownership subsidy. More than 80% of the $160 billion in foregone revenues from the deduction for mortgage interest and property tax payments goes to households in the top income quintile. The other is to introduce a modest tax on financial transactions.

But should the focus be confined to steps that make the tax system more progressive? Many on the left view heightened progressivity as the key to inequality reduction. Yet in the United States and other rich countries the tax system overall, including taxes of all types and at all levels of government, is essentially flat; households throughout the income distribution pay roughly similar shares of their market income in taxes. As the following chart shows, inequality reduction is achieved not through taxation but with government transfers (and services).

Taxes help to reduce inequality mainly via their quantity rather than their progressivity. The greater the tax revenues, the more government is able to boost incomes and living standards of those in the lower half of the distribution with transfers and services.

Moderate or high levels of tax revenue can’t come solely from higher rates or new taxes on the rich; the math simply doesn’t work. To significantly increase spending on transfers and/or services, President Obama and/or his successors will need to increase taxes on the middle class. One way to do this would be via a federal consumption tax, such as a value-added tax (VAT). We have state and local consumption (sales) taxes, but we raise less money from consumption taxes than any other rich country. Consumption taxes are regressive, and for that reason they’re often dismissed by the American left. But they can be tweaked to limit the degree of regressivity. And if the money is put to progressive use, the benefits may outweigh this drawback.

In my view, raising and indexing the minimum wage, enhancing the Earned Income Tax Credit, and expanding and improving public services ought to be our top priorities for boosting the incomes and living standards of Americans in the lower half of the income distribution. What about the other component of rising inequality: soaring incomes of those in the top 1%?

It’s tempting to want to intervene directly in markets to reverse this trend. One way to do so is to legislate some sort of pay cap — a maximum wage, if you will. I don’t think this is the right way to go. If the value-added by particular individuals — a CEO, financial innovator, top athlete, movie star, or what have you — is sufficient to merit pay above the cap, firms will figure out ways to get around it, for instance by providing non-monetary perks or deferring pay.

Stricter regulation of the financial sector is another possibility. This is a good idea, though mainly to prevent a repeat of the current economic downturn. If doing so has the indirect effect of reducing enormous payouts to financial players, so much the better.

The simplest and best strategy is to let markets largely determine high-end earnings and incomes and use the tax system to redistribute (more here and here). We should increase the top income tax rate and/or add one or more new rates for those with very high incomes.

This would help to reduce income inequality. And it follows logically from the rationale for progressive taxation: the higher your income, the larger the share of it you can afford to pay in taxes. Since high-end pretax incomes have risen sharply in recent decades, those at the top can afford to pay a greater share of those incomes in taxes than they did in the past. So far they haven’t had to do so, as the following data on the top 0.01% of households (about 10,000 households) indicate. This group’s average inflation-adjusted pretax income soared from $7 million in 1979 to $35 million in 2005, but the share of that income they paid in taxes didn’t increase.

What’s the proper effective tax rate on top incomes? It’s the rate that is consistent with fairness norms and produces the most tax revenue without (significantly) reducing work, investment, and innovation. I don’t know what that rate is. Maybe it’s 40%. Perhaps it’s 50% or 60%. It could conceivably be even higher. Figuring this out requires policy adjustment and monitoring.

How do we boost the incomes of Americans in the lower half (or two-thirds) of the distribution? I’ve discussed what I think are some helpful and some probably-not-so-helpful proposals. But our focus shouldn’t be exclusively on income. The well-being of lower- and middle-class Americans can be improved markedly by enhanced provision of government services.

Service use (consumption) doesn’t show up in income statistics. But services matter for living standards. If I have two kids in a public school that spends about $10,000 per year per child, I’m receiving the equivalent of a government transfer of $20,000. Other public services and public spaces — health care, child care, policing, transportation, roads, parks, libraries, and so on — have the same property. So too does free time funded or mandated by government via holidays and paid parental leave.

When provided by government at little or no cost to users, these services are akin to a transfer given in equal dollar amounts to all individuals or households. Our tax system is roughly flat: households at different points in the income distribution pay approximately the same share of their market (pretransfer-pretax) income in taxes. But a flat tax rate means those with high incomes pay many more dollars in taxes than do poor households. If the value of the government services the rich and poor use is roughly the same in dollars, then the tax-services system overall is quite redistributive. Here’s a way to see this, using tax payment data for 2004 and hypothetical data for consumption of public services:

Some services charge user fees that are structured progressively; those with higher incomes pay more. This makes the tax-services system even more redistributive. Financial aid means this is true for public (and many private) colleges here in the U.S., though we could go much farther. In Denmark and Sweden, fees for child care are scaled according to household income.

Imagine an America in which high-quality public services raise the consumption floor to a high level: most citizens can put their kids in high-quality child care followed by good public schooling and affordable access to a good college; they have access to good health care throughout life; they can get to or near work on clean and efficient public transportation or roads with limited congestion; they enjoy clean and safe neighborhoods, parks, roads, museums, libraries, and other public spaces; they have low-cost access to information, communication, and entertainment via reliable high-speed broadband; they have four weeks of paid vacation each year, an additional week or so of paid sickness leave, and a year of paid family leave to care for a child or other needy relative. Even if the degree of income inequality were no less than today and we still had CEOs, financiers, and entertainers raking in tens or hundreds of millions of dollars in a single year, that society would be markedly less unequal than our current one.

It’s worth emphasizing that markets too boost the consumption floor. New technologies and consumer products — indoor plumbing, cars, air conditioning, cell phones, ipods, and many others — have eventually become affordable for even the least well-off, and in doing so they reduce inequality of living standards. But markets haven’t, and likely won’t, bring us affordability coupled with high quality in health care, education, child care, safety, and mass ground transportation. In these and other areas, government is needed.

The United States provides less in the way of public services than many other rich countries, but we nevertheless have a rich history here, from universal elementary and secondary education to the interstate highway system to the internet. There’s a legacy to build on, and good reason to do so.

So far in this series of posts on reducing income inequality in America I’ve said that it would be good if there were less inequality, that greater unionization might help but probably isn’t in the cards (even if EFCA becomes law), that more and better education would be a good thing but isn’t likely to make much of a dent in the inequality problem, and that curtailing globalization is a bad choice for progressives even if it would help a lot. So what should we do?

Recall that there are two key components of the rise in inequality: slow income growth in the lower half (or two-thirds) of the distribution and soaring incomes at the top. Let’s start with the first of these two. I think a key component of an effective and politically feasible strategy is an enhanced statutory minimum wage and Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC).

This year the minimum wage will increase to $7.25 per hour. I’d like to see it raised again in 2010, to $8.00. A more important change is to index the minimum wage to inflation. As the following chart shows, since the late 1970s the minimum wage has been allowed to languish for lengthy periods with no increase, resulting in large declines in its inflation-adjusted value. With increases in 2007, 2008, and 2009, it will be at a reasonably high level compared to the past three decades, though still below its late-1960s peak. Raising it to $8.00/hour and keeping it at that value would be a significant step in the right direction.

Trade, outward foreign investment (movement of plants and services abroad), and immigration very likely have contributed to the growth of U.S. earnings inequality over the past several decades. Reducing any or all of them might well help to boost wages among Americans in the lower half of the distribution.

But in my view this shouldn’t be even a minor part of a strategy for inequality reduction, much less its chief focus. Trade, investment abroad, and immigration tend to benefit citizens in and from poor countries, which includes the bulk of the world’s population. Most of these people are substantially poorer than even the poorest Americans.

Yes, globalization enriches some rapacious corporations and despotic rulers, and vulnerable workers are exploited. But access to the American market and to employment by U.S.-based transnational firms has helped improve the lives of hundreds of millions of Chinese, Indians, and others in recent decades. And moving to the United States almost invariably enhances the living standards of immigrants from poor nations. It would be a bitter irony if American progressives succeeded in making a real dent in our inequality problem at the expense of the world’s poorest and most needy. We can, and should, look elsewhere for solutions.

I’m not suggesting we should sit idly by and let globalization have its way with the Americans who lose their jobs or experience falling wages. But rather than try to slow or block globalization, we should instead do what we can to enhance their flexibility and adaptability and to provide adequate cushions and supports. Among the things we Americans can learn from the Danes, Swedes, and Dutch, one of the most valuable is that it’s possible to embrace globalization (and other sources of economic change and disruption) and still have a high-opportunity, low-inequality, low-poverty society. The following chart offers one indication of this. It shows earnings inequality by imports as of the mid-2000s. Import-heavy countries are by no means doomed to high inequality.

Most of us want policies like wage insurance, better unemployment compensation, portable health insurance and pensions, support for retraining, and assistance with job placement not just because they can help to blunt the adverse consequences of globalization, but because they do so for economic change in general — whether it’s a product of technological progress, geographical shifts of industries and firms within the United States, or what have you. Arguing for limits on globalization directs attention away from these policies, making their adoption less likely. Paradoxically, then, we end up with the worst of both worlds: marginal trade limits, half-hearted steps to curtail investment abroad, confused and ineffective immigration policy, and too little of the supports and cushions needed for successful adjustment.

If you don’t like my take on this, consider what the following have to say before you make up your mind: Alan Blinder, Paul Collier (ch. 10), Brad DeLong, James Galbraith, Nicholas Kristof, Paul Krugman, Dani Rodrik (ch. 9), Amartya Sen (ch. 4), Gene Sperling, Joseph Stiglitz (ch. 3).

When social scientists first began noticing and studying the rise in earnings and income inequality in the United States, much of the focus was on technological change. The idea is that in the past generation technology — especially computerization — has advanced more rapidly than skills, so employers have bid up pay for those able to use and improve new technology and reduced pay for (or gotten rid of) employees less adept at doing so.

Though this remains perhaps the single most popular explanation, many are skeptical. In their book The Race between Education and Technology, Claudia Goldin and Lawrence Katz offer an especially compelling critique. They suggest that the pace of skill-biased technological advance actually hasn’t changed much over the past century. What distinguishes recent decades, they contend, is that growth of educational attainment has slowed. Here’s their key picture (the vertical axis shows the share with a college degree):

Unionization in the United States has been declining since the 1950s, and at a particularly rapid clip since the 1970s. Many analysts who have studied the growth of income inequality in America over the past several decades agree that union decline has played a role, and some see it as the single most important factor. The Employee Free Choice Act (EFCA), which would make it easier for employees to unionize, stands a chance of becoming law in the next year or two. Would that help to reverse the rise in inequality?

I’m not optimistic. An increase in unionization would very likely help middle and low-end households to capture a larger share of economic growth. But even if EFCA is passed by Congress, I don’t expect a dramatic surge in union membership.

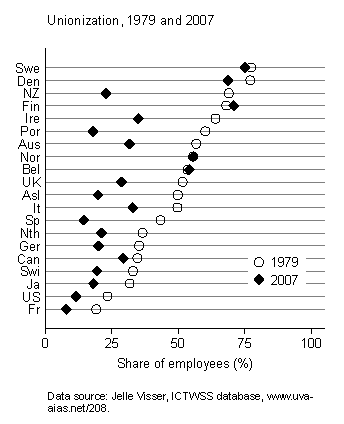

Yes, survey evidence suggests that many American workers who aren’t currently a union member would like some sort of organized representation. And yes, American labor law and its weak enforcement have been a key culprit in union decline. Yet other rich countries have labor law that’s much more favorable to unions, and unionization has been declining in most of them too. Consider the following figures, from the best available comparative data source. Only a few countries have avoided a sharp fall in unionization, and they’re mainly ones in which eligibility for unemployment insurance is tied to union membership.

Why the widespread decline in unionization? The causes are multiple: greater competition and profit pressure on employers, the shift from manufacturing to services, increases in part-time and temporary employment, shrinking public sectors, and attitudinal shifts across generations, among others.

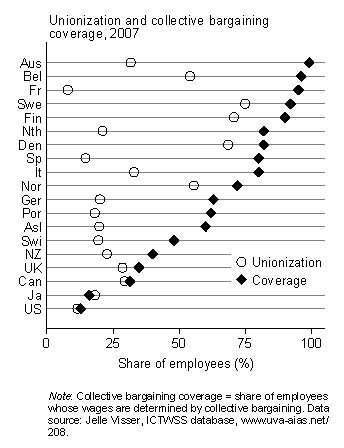

How then are unions in other countries able to secure greater wage gains, and thus less inequality, than their American counterparts? The key is “extension” practices: by agreement between union and employer confederations (most nations) or due to government mandate (France), union-management wage settlements apply to many firms and workers that aren’t unionized. The following chart shows that in a number of countries the share of the workforce whose wages are determined by collective bargaining is much larger than the share of workers who are union members.

I would like to see EFCA become law. The ability of workers to bargain with management collectively rather than individually is, in my view, an important element of a just society, and these days the playing field is too heavily tilted in management’s favor. But I doubt EFCA will get us very far in reducing income inequality. Extension of union-management wage settlements would likely have a bigger impact, but at the moment that isn’t even part of the discussion.

As Henry mentioned this morning, I’ll be doing a series of guest posts at Crooked Timber this week. I’m grateful for the invitation. My posts will be on strategies for reducing income inequality in the United States.

Here’s the problem (more discussion here):

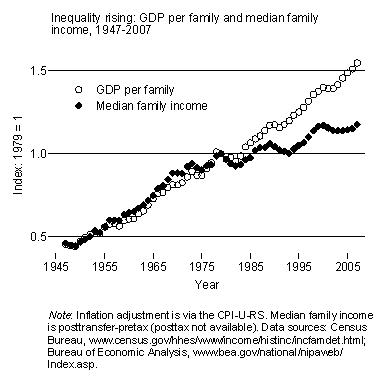

There are two linked components to this rise in inequality: the surge in incomes for those at the top of the distribution and the slow growth of incomes for those in the middle and at the bottom.

Is this really a problem? Would it be better if income inequality were reduced? I think so, for the following reasons.

1. Fairness. Market processes have produced enormous incomes for various financial operators, CEOs, entrepreneurs, athletes, and entertainers in recent decades. A good bit of this is due to luck — being in the right place at the right time, genetic talent, having the right parents or teacher or coach, and so on. I don’t mind some inequality due to luck, and I recognize that monetary incentives are helpful. But the current (or recent, I should say;Â the downturn will reduce top incomes somewhat) magnitude of inequality in America strikes me as unfair. An income of several hundred million dollars when the minimum wage gets you about $15,000 is too much inequality. What’s the proper amount of income inequality? I don’t have a precise answer, but that doesn’t mean it’s wrong to feel that our current level is excessive.

2. Inequality’s consequences. Even if you don’t worry about exorbitant incomes in and of themselves, there’s no avoiding the fact that they have consequences for the incomes and well-being of Americans in middle and lower parts of the distribution. The social pie isn’t zero-sum. But our economy hasn’t grown faster in the past few decades than it did before, so the dramatic jump in incomes among those at the top has come in part at the expense of the rest of us. The following chart offers one way to see this. It shows GDP per family and median family income over the past six decades. Relative to growth of the economy, incomes in the middle (and below) have increased slowly since the 1970s.

As Robert Frank has pointed out, super-high incomes also have led to an arms race in consumption, especially in housing. Spending among the rich has escalated dramatically, encouraging middle- and upper-middle-class households to take on more and more debt in order to keep pace.

Over the past decade a number of social scientists have looked at the effect of inequality on other societal outcomes. We have studies suggesting that inequality is bad for education, health, crime, economic growth, economic mobility, civic engagement, political participation, political influence, and political polarization. I’m not convinced that all of these findings are correct, but some of them are quite plausible.

So what should we do? Stay tuned.

One of the effects of the Global Financial Crisis is that the window of ideas now regarded as thinkable has expanded greatly. Willem Buiter typically works close to the edge of the window, but even so, I doubt that he would have written this in the Financial Times a year ago:

[Tax havens] should be closed down.

The easiest way to achieve this is to make it illegal for any natural or legal person from a non-tax haven country to do business with or enter into transactions with any natural or legal person in a tax haven. That ought to do it. Tax haven, again, is defined not with respect to tax rates or tax bases, but with respect to bank secrecy, that is, with respect to the information shared by the country’s financial institutions with foreign tax authorities. That information sharing should be automatic and comprehensive.

As regards regulatory havens, once common G20 standards for regulatory norms, rules and regulations has been set, countries that violate these standards would be black-listed. The obvious sanction is non-recognition of contracts drawn up in the regulatory haven jurisdiction and non-recognition of court decisions in these regulatory havens. That ought to do it.

The logic hasn’t changed in the last year, but the idea that the OECD could simply cut off economic interactions with places like the Cayman Islands and Liechtenstein (let alone, say, Switzerland) wasn’t thinkable then. It is now.

Update Marshall McLuhan moment: In comments, Willem Buiter points to this piece, written a year ago, and taking an equally strong line. Despite getting this example wrong, I still think the window has shifted.

I’ve just been at a fascinating conference on Evidence, Science And Public Policy. It was worth the trip just to hear John Worrall on evidence-based medicine point out this paper on remote retroactive intercessory prayer[1]. Assuming, as appears to be the case, that the study was totally legit (no data mining etc), the obvious question for me was why anyone would think it worthwhile (ex ante) to test this out.

But that’s not the subject of this post.

Suppose Obama came out and said, roughly:

My fellow Americans, the thing about the Geithner plan is this. Experts disagree about the nature of the crisis. Either it is a liquidity problem or an insolvency problem. That means: either the market values of these so-called toxic assets are depressed because of a kind of market failure; or the market has priced these assets more or less correctly and many institutions holding these assets are, as a result, insolvent. If we are indeed in a liquidity crisis, the Geithner plan should solve it as well as any alternative plan could. If it is an insolvency crisis, however, as many experts believe, the Geithner plan will do nothing – or not nearly enough.

If the Geithner plan fails, we will confront another either/or: either nationalize these too-big-to-fail institutions, at great cost, or allow them to fail, collapsing the global financial system and, very likely, the world economy. This is no true choice, however. Hard as nationalization will be, if it comes to that, the alternative would be far, far worse.

We do not need to take this daunting step of nationalization yet because, first, we’re trying the Geithner plan. What you should know about the Geithner plan is that, if it fails, it will still have been worth trying. We will have determined that the problem is indeed insolvency. We will have clarified the path to be taken, laid to rest any reasonable skepticism about the strict need for nationalization. And we will have paid no more for this knowledge than we would have had to pay in any case. If the government effectively transfers money to distressed financial institutions, under the Geithner plan, and later those institutions have to be nationalized for a time, there is no need to ‘pay twice’. [click to continue…]