The Boston Review symposium I pointed to last year on James Heckman’s “Promoting Social Mobility” is now out in book form as Giving Kids a Fair Chance. Its all still on the web, at least right now, but the book is cute and inexpensive. I’m curious what other people’s experience is, but I find that when I assign a book in class it gets read by more students, and more carefully, than if I assign something from the web; so I am planning to use it alongside Unequal Childhoods

with my freshman class in the fall.

From the category archives:

Education

There’s a very good piece by Jal Mehta in the Times last Sunday, reflecting on A Nation at Risk. He criticizes not teachers, but the profession of teaching:

Teaching requires a professional model, like we have in medicine, law, engineering, accounting, architecture and many other fields. In these professions, consistency of quality is created less by holding individual practitioners accountable and more by building a body of knowledge, carefully training people in that knowledge, requiring them to show expertise before they become licensed, and then using their professions’ standards to guide their work.

By these criteria, American education is a failed profession. There is no widely agreed-upon knowledge base, training is brief or nonexistent, the criteria for passing licensing exams are much lower than in other fields, and there is little continuous professional guidance. It is not surprising, then, that researchers find wide variation in teaching skills across classrooms; in the absence of a system devoted to developing consistent expertise, we have teachers essentially winging it as they go along, with predictably uneven results.

I’m very uneasy with his subsequent comparisons with countries that do better, though — Singapore, Japan, South Korea, Finland, Canada — which lack large swathes of relative poverty and, in a couple of cases authoritarian cultures. Its not as though these countries have developed technologies for teaching the kinds of student that American schools educate. But he makes an interesting point about why we know so little, and so little of what we do know is usable:

Anthony S. Bryk, president of the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, has estimated that other fields spend 5 percent to 15 percent of their budgets on research and development, while in education, it is around 0.25 percent. Education-school researchers publish for fellow academics; teachers develop practical knowledge but do not evaluate or share it; commercial curriculum designers make what districts and states will buy, with little regard for quality.

Anyway, there’s lots of good stuff, so read the whole thing.

[My reflections on Britain since the Seventies](https://crookedtimber.org/2013/04/10/britain-since-the-seventies-impressionistic-thoughts/) the other day partly depended on a narrative about social mobility that has become part of the political culture, repeated by the likes of Tony Blair and Gordon Brown and recycled by journalists and commentators. In brief: it is the conventional wisdom. That story is basically that Britain enjoyed a lot of social mobility between the Second World War and the 1970s, but that this has closed down since. It is an orthodoxy that can, and has, been put in the service of both left and right. The left can claim that neoliberalism results in a less fluid society than the postwar welfare state did; the right can go on about how the left, by abolishing the grammar schools, have locked the talented poor out of the elite. And New Labour, with its mantra of education, education, education, argued that more spending on schools and wider access to higher education could unfreeze the barriers to mobility. (Senior university administrators, hungry for funds, have also been keen to promote the notion that higher education is a social solvent.)

[click to continue…]

The 1970s have been in my mind over the past few days, not only for the obvious reason, but also because I visited the Glam exhibition at Tate Liverpool last weekend. Not only were the seventies the final decade of an electrical-chemical epoch that stretched back to the late nineteenth-century, they were also the time when the sexual and political experimentation of the 1960s and a sense of being part of a cosmopolitan world order became something for the masses, for the working class, and when the old social order started to dissolve. In the experience of many people, the sixties happened in the seventies, as it were.

But my main thoughts, concerning Britain at any rate, have been about social division, and about some oddly paradoxical features of British life before Thatcher. There’s a very real sense in which postwar British society was very sharply divided. On the one hand, it was possible to be born in an NHS hospital, to grow up on a council estate, to attend a state school, to work in a nationalised industry and, eventually (people hoped), to retire on a decent state pension, living entirely within a socialised system co-managed by the state and a powerful Labour movement. On the other, there were people who shared the experience of the NHS but with whom the commonality stopped there: they were privately educated, lived in an owner-occupied house and worked in the private sector. These were two alternate moral universes governed by their own sets of assumptions and inhabited by people with quite different outlooks. Both were powerful disciplinary orders. The working class society had one set of assumptions – welfarist, communitarian, but strongly gendered and somewhat intolerant of sexual “deviance”; middle-class society had another, expressed at public (that is, private) schools through institutions like compulsory Anglican chapel. Inside the private-sector world, at least, there was a powerful sense of resentment towards Labour, expressed in slogans about “managers right to manage” and so on that later found expression in some of the sadism of the Thatcher era towards the working-class communities that were being destroyed. Present too, at least in the more paranoid ramblings of those who contemplated coups against Labour, was the idea that that the parallel socialised order represented a kind of incipient Soviet alternative-in-waiting that might one day swallow them up.

[click to continue…]

In his (relatively) new gig as business and economics correspondent at Slate, Matt Yglesias is really churning out lots of material. Often, it’s useful and insightful, but, inevitably quality control is imperfect. Arguably, there’s still a net benefit from the increase in output, provided readers apply their own filters. Nevertheless, I got a bit miffed by this post, which makes a mess of a topic, I’ve covered quite a few times, namely the question of whether US middle class living standards are declining as regards services like higher education.

As I’ve pointed out, the number of places in most Ivy League colleges has barely changed since the 1950s, and many top state universities have been static or contracting since the 1970s. In addition, the class bias in admissions has increased. College graduation rates have increased modestly since the 1970s, but an increasing proportion of post-school education is at lower-tier state universities as well community colleges offering only associate degrees.[1]

(Added in response to comments): Given static numbers at the top institutions, increasing populations, and a reduced share of admissions going to the middle class, education at the kinds of colleges usually discussed in this context (the top private and state universities) is an example where the middle class (roughly, the middle three quintiles) are getting less than they did 40 years ago. They’ve substituted cheaper second-tier and third-tier institutions where tuition, while rising fast, is much lower than at the Ivies, top state unis etc. But the chance of getting into the upper middle class (top quintile) with a degree from these schools is correspondingly lower. So, education as a route out of the middle class and into the top quintile is less accessible than forty years ago – this is leading to a reduction in already limited social mobility.

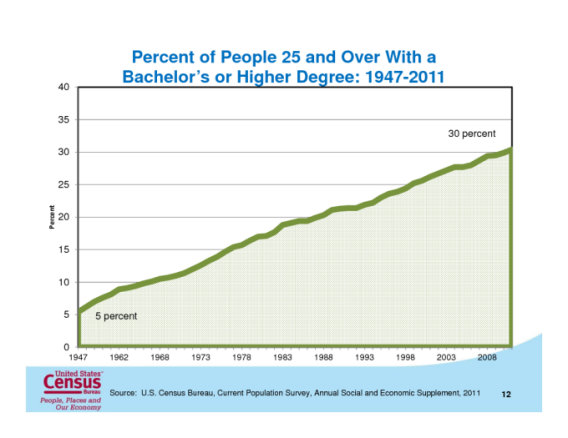

Yglesias says “Colleges charge much higher prices today than they did 40 years ago but many more people have college degrees” and backs this up with the following graph

What’s wrong with this picture?

[click to continue…]

Very interesting – and long – bloggingheads discussion on the future of higher education in the age of MOOCs – Udacity, Coursera – between Tamar Gendler and Clay Shirky. Shirky’s thesis: Napster got killed but its brief and dramatic algae-bloom of a life changed the ‘story’ of music distribution. No going back. So now we have iTunes and other stuff and record companies don’t look like they once did. Likewise, maybe Udacity isn’t the future, but the ‘story’ changes after recent, dramatic successes. That’s a wishy-washy way for me to put it, but it is one of those ‘the revolution is coming but we can’t know what it will be like yet’ prophecies, which are inherently – and sensibly! but frustratingly! – bet-hedging. Here’s a slightly more concrete way to cash out ‘story’: we tend to operate with notions of the proper form and function of the university that are too closely tied to pictures of the ideal college experience that are, really, too atypical to function as paradigms. ‘We’ meaning pretty much everyone still: academics, our students, their parents. Shirky’s idea is that MOOCs are going to unbundle a lot of stuff. You don’t have to buy the 4-year package to get some learning. It’s pretty obvious there’s more unbundling to come – it’s gonna make buying individual tracks on iTunes seem a minor innovation – and it will put pressure on current higher education’s strong tendency to bundle a lot of functions together to the point of indistinguishability (teaching, research, socialization, credentialing). Beyond that, the success stories about these MOOC’s are going to shift our sense of what is ‘normal’ to such a degree that there will be no going back. It has a lot to do with how previously under-served populations will inevitably be much better served; that’s going to become too obvious for old ways of doing it to continue to seem at the center of higher education. (Now I’m back to being vague, while also sounding radical. Sorry about that. Read Clay’s piece on all this – probably you’ll have to wait for his blog not to be down, which it appears to be at the moment.) [click to continue…]

So homeschooling is turning out to be kind of like sobriety? Which started as a joke–and no, I am not an alcoholic or addict, except for being a former smoker, which does, actually, count–but on thinking about it, I wonder if there might, actually, be a more than casual relationship between addiction and “giftedness” that’s like the one between “giftedness” and depression. Or for that matter, addiction and mental illness. At least, in my experience of the latter, a big part of the problem is the gap between conception and reality. One sees problems globally and is overwhelmed by realizing that you can only chip away at them in tiny increments, or imagines a fabulous project or goal but is frozen with anxiety by not knowing how to start, or by perceiving the enormous gap between starting and actually achieving the thing. [click to continue…]

I must make a Public Statement about Women Who Breastfeed While Teaching. Because I am a woman who used to teach, and I breastfed, and though I never breastfed my kid during class I did on occasion bring him while I was teaching. And I think I may have breastfed him during at least one faculty meeting.

In the thread on community colleges (which morphed into a discussion of more general education and management issues), someone mentioned Kahneman on the “halo effect” in grading (or marking) student work. _Thinking Fast and Slow_ has been on my to-read pile since Christmas, but I got it down from the shelf to read the relevant pages. Kahneman:

bq. Early in my career as a professor, I graded students’ essay exams in the conventional way. I would pick up one test booklet at it time and read all the students’ essays in immediate succession, grading them as I went. I would then compute the total and go on to the next student. I eventually noticed that my evaluations of the essays in each booklet were strikingly homogeneous. I began to suspect that my grading exhibited a halo effect, and that the first question I scored had a disproportionate effect on the overall grade. The mechanism was simple: if I had given a high score to the first essay, I gave the student the benefit of the doubt whenever I encountered a vague or ambiguous statement later on. This seemed reasonable … I had told the students that the two essays had equal weight, but that was not true: the first one had a much greater impact on the final grade than the second. This was unacceptable. (p. 83)

Kahneman then switched to reading all the different students’ answers to each question. This often left him feeling uncomfortable, because he would discover that his confidence in his judgement became undermined when he later discovered that his responses to the same student’s work were all over the place. Neverthless, he is convinced that his new procedure, which, as he puts it “decorrelates error” is superior.

I’m sure he’s right about that and that his revised procedure is better: I intend to adopt it. Some off-the-cuff thoughts though: (1) I imagine some halo effect persists and that one’s judgement of an immediately subsequent answer to the same question in consecutive booklets or script is influenced by the preceding one; (2) reading answers to the same question over and over again can be even more tedious than marking usually is. I thing it would be even better to switch at random through the piles; (3) (and this may get covered in the book) the fact that sequence matters because of halo effects strikes me as a big problem for Bayesians. What your beliefs about something end up being can just be the result of the sequence in which you encounter the evidence. If right (and it’s not my department) then that ought to be a major strike against Bayesianism.

David Graeber’s three social principles – hierarchy, exchange and communism – are useful devices to think about the world, particularly when you become sensitized to the way in which one can turn into or mask another. One site of human interaction that may be illuminated by Graeber’s principles is the modern university: perhaps especially the British version which has evolved from nominally democratic modes of governance to extremely hierarchical ones within a generation.

[click to continue…]

So. That post I wrote about charter schools? Where I argued that liberal, educated, reasonably affluent parents (like me!) should keep our kids in public schools, advocate for public schools, not buy our way out of problems in the public schools, and so on? Dana Goldstein made a similar argument against homeschooling recently.

Only some things have happened since I wrote that post, and as it turns out, I’m homeschooling Pseudonymous Kid right now. [click to continue…]

Some more IT-in-Education nerdery. I want to rebut an idea that’s been doing the rounds as people have been thinking further about Apple’s strategy in the education market. On last week’s Hypercritical, John Siracusa discussed a recent post by McKay Thomas which argued that Apple is following a “brilliant strategy” in education of “going high school first [and] applying the heat to university textbook publishers and bookstores”. John Gruber linked to it as well. Here’s Thomas:

The new iBook textbooks are being marketed in a way that circumvents the university bookstore. Brilliant. Go right to the student in high school. Make them a true believer. Give them an amazing textbook experience starting in 9th grade. By the time these students hit university in 4 more years they aren’t going to know how to not use an iPad while studying.

I don’t think this is right. The bookstore isn’t nearly as important as Thomas imagines. In fact, colleges are much more open to adoption of new technology and curriculum than grade schools for the simple reason that university faculty decide the content of their own courses. This isn’t to say every worthwhile innovation is widely and rapidly taken up, or that everything that diffuses is worthwhile. But when it comes to textbooks, colleges are far more porous than schools.

Yesterday Apple launched some new applications and services aimed at the education market. They extended the iBooks app to include a textbook store; they announced some deals with major textbook publishers; and they released a free application you can use to write textbooks, and which allows you to publish them on the store. They made their iTunes U service a separate application. The app replicates what’s already available on iTunes, but also seeks to replace some or all of what’s offered by course management systems.

Another great radio piece by Emily Hanford (I caught the end of what I assume was just part of it on the NPR afternoon news show on Sunday) here (audio and transcript both there). She reports the research on the effectiveness of lectures in prompting actual learning: not much. Anyone reading who lectures must listen to/read it. A long excerpt (followed by some comments):

Lecturing was the way just about everyone taught introductory physics. To think there was something wrong with the lecture meant physics instructors would “have to really change the way they do things,” says Hestenes. A lot of them ignored his study and kept teaching the way they always had. They insisted their lectures were working just fine. But Eric Mazur was unusual, says Hestenes. “He was the first one who took it to heart.” Mazur is a physics professor at Harvard University. He came across Hestenes’s articles in 1990, five years after they’d been published. To understand why the articles had such a big impact on Mazur you have to know some things about his history. Mazur grew up dreaming of becoming an astronomer.

“When I was five years old I fell in love with the universe,” he says. “I tried to get my hands on to every accessible book on astronomy. I was so excited by the world of science.” But when Mazur got to university, he hated the astronomy classes.”It was all sitting in the lecture, and then scribbling down notes and cramming those notes and parroting them back on the exam,” he says. “Focusing on the details, focusing on memorizing and regurgitation, the whole beauty of astronomy was lost.” So he switched to physics. It wasn’t as heartbreaking for him to sit in a physics lecture and memorize things. Mazur eventually got a Ph.D. in physics and a job at Harvard University. Like most Ph.D.s, Mazur never got any training in how to teach.

Commenter MS asked <a href=”https://crookedtimber.org/2011/12/06/howdy/#comment-390689″>what I think about charter schools</a>, which as it happens is something I have opinions on. (I know, go figure.)

I am a die-hard pro-public-schools liberal, in a nutshell. I wasn’t real keen on charter schools from the beginning: while I’m all for the idea that educators and schools ought to be allowed, dammit, to try innovative or new approaches, it was clear that demanding that “regular” public schools conform to the one-test-fits-all-and-here-is-THE-mandated-curriculum approach while setting up alternative schools that were magically freed of that bullshit while still being the financial responsibility of the school district was pretty much a recipe for trying to further siphon money out of public schools while beating teachers up for failing to educate 30-40 kids in a class with the change they could find at home in their couch cushions.

Funnily enough, that concern was founded on an expectation that charter schools, freed from some of the regulations that public schools have to adhere to, would, in fact, manage to offer better educations. It turns out that that’s not actually the case, though; by now we all know that the results comparing charters to public schools are mixed; there is no clear advantage to charter schools. My guess is that founding schools based on half-baked theories and ideologically driven philosophies, or as for-profit institutions, rather than oh, say, based on actual evidence about what works in education, isn’t the way to go.

The problem, of course, is that most of us aren’t experts in educational research; I’m highly interested in pedagogy, and know a lot more about what works and what doesn’t than most people, but it isn’t a field I’m trained in, I don’t read education journals regularly, and I would not claim to be an expert on this stuff. So we can’t, honestly, expect parents to pick schools based on their knowledge of what’s educationally beneficial.

That said, obviously parents in general can be trusted to know their own personal kid pretty well, and I think there’s a decent case to be made that parents ought to have the ability to send their kid to, say, a school with a heavy focus on the social aspect of learning, where there’s a fair bit of noise and chaos and no individual desks and lots of moving around the classroom; or to recognize that their kid is easily distracted and kinda likes the pen-and-paper model of learning and finds it easier to get stuff done while sitting in one of several rows all facing the teacher. (I have sent my kid to both kinds of schools, just fyi.)

There’s an even better case to be made that individual teachers should have the ability to try new ideas in their classrooms. After all, teachers, unlike parents, are actually trained in education, and they have a lot more experience than parents do of how things actually go in a classroom (and of what their own strengths and weaknesses are, and how much patience they have to deal with, say, a socratic approach where kids are encouraged to argue, or to put up with building materials all over the classroom for weeks while the kids construct some awesome physics experiment).

But right now the focus is entirely on parent choice, which, if nothing else means that the children of parents who are motivated to seek out schools that fit their kid or their beliefs about education are going to benefit, if there are benefits to be had, while kids whose parents are either less motivated or less financially able to move to a different neighborhood or afford the gas and time to transport their kids back and forth every day or research and follow up on what’s going on at school, are going to have to deal with what’s left over.

Which basically is my own personal bottom line, as well as–as we’ve seen over and over–<i>the</i> bottom line. The children of people who read academicish blogs are *going to be fine no matter what*. If my kid is going to a school that doesn’t have a librarian (which he did from grades 2-5), well, he has three six-foot bookshelves at home plus piles of books on his bedside table and floor. If his teacher isn’t super patient with his temper, he has a mother who is going to schedule meetings with the teacher to advocate for his emotional needs and then come home and figure out how to explain to him, in a way that he can sign on to, why he needs to manage his frustration and how we’re going to help him do that. If his school doesn’t offer music or art or science classes, and he is interested in those things or I think they’re important, I can arrange for those things privately.

Meanwhile, I’m highly aware that any system that’s set up to siphon money and ideas away from the base option is going to end up impoverishing the base option, right? If the problem is that the base option isn’t good enough or flexible enough, then we need to address that, not create some kind of parallel system. Especially if that parallel system functions as an implicit “alternative” to a default that “isn’t good enough.” If it isn’t good enough for my kid, it isn’t good enough for anyone’s kid. And if my kid is in a public school, then let’s be honest: I’m going to be far, far more proactive than I otherwise would about improving that school, and public schools in general (for example, I created a bit of a curriculum library at his last school, and at his current one I’ve been highly proactive in pushing the administration to deal with bullying).

And finally, the other really major reason for the kids of educated white folks like me to stay in public schools is that we are still a highly segregated society. As my own kid said the other day, “the easiest way to realize that poor people are not lazy or stupid is to have friends that are poor.” Substitute any group and stereotype that you want into that sentence (He also recently commented that he’s always had classes with kids who had “some kind of disability that makes them shout or act out or be really distracting in class” which led us to a conversation about how common learning/behavior/mental disorders are.) I think in our cultural push to “raise standards,” we’ve overfocused on traditional academic standards. Yet one of the things our society suffers most from–and the way we’ve approached academic standards echoes it–is the worship of extreme individualism. We need to keep in mind that our kids are not just my kid or your kid or the anonymous kids of “those” people over there: they are all <i>our</i> kids, and we have a collective duty and responsibility to model public citizenship to them. One of the best ways to do that is to participate in public institutions.