You searched for:

utopias

A piece I wrote elsewhere in March is doing the rounds again. ‘The Prodigal Tech Bro’ is about the privileged place in professional interactions and public discourse given to men who used to work in senior positions for tech platforms and are now surprised and disturbed by what those companies do. It points out how the ex-tech executives’ “I’m was lost, now I’m found; please come to my TED talk” redemption arc misses out a key part of the narrative groove they use to slide back into our good graces. It’s the bit in the Biblical parable of the Prodigal Son where he hits rock bottom in a pigsty and decides to go home and beg to be taken on as one of his father’s servants. Ultimately, he’s forgiven, much to the chagrin of the brother who stayed home and did the work, but the original Prodigal Son understands where he went wrong, and more importantly who he has wronged, and believes all the long walk home that he will never regain his former status and comfort.

A new documentary on Netflix, The Social Dilemma, is about the harms of social media. It centres the wide-eyed gradualism of a former tech executive named in my piece, amongst others whose careers have followed a similar trajectory from poacher to … someone who thinks we should maybe sometime think about hiring some more gamekeepers, if that’s ok, though obviously not the radical gamekeepers, and definitely not gamekeepers who think their job is something more than game-keeping the herd so ‘we’ can conveniently shoot or farm it.

The film repeats the same failing of the former tech execs – it assumes that the privileged people who made the mess we’re all in should be at the centre of the conversation on how to clean their shit up, crowding out once again those who have suffered because of their shit, or who’ve wrecked their careers by speaking loudly about the existence of this shit, and – crucially – limiting our thinking about what we do now to the homeopathic solutionism of the slurry-drenched insider who is already defined by his insistence that what looks, smells and acts like shit is not, in fact, shit. [click to continue…]

David Brion Davis, the pathbreaking Yale historian of slavery and emancipation, whose books revolutionized how we approach the American experience, has died. The obituaries have rightly discussed his many and manifold contributions, a legacy we will be parsing in the days and months ahead. Yet for those of us who were graduate students at Yale during the 1990s and who participated in the union drive there, the story of David Brion Davis is more complicated. Davis helped break the grade strike of 1995, in a manner so personal and peculiar, yet simultaneously emblematic, as not to be forgotten. Not long after the strike, I wrote at length about Davis’s actions in an essay called “Blacklisted and Blue: On Theory and Practice at Yale,” which later appeared in an anthology that was published in 2003. I’m excerpting the relevant part the essay below, but you can read it all of it here [pdf].

* * *

As soon as the graduate students voted to strike, the administration leaped to action, threatening students with blacklisting, loss of employment, and worse. Almost as quickly, the national academic community rallied to the union’s cause. A group of influential law professors at Harvard and elsewhere issued a statement condemning the “Administration’s invitation to individual professors to terrorize their advisees.” They warned the faculty that their actions would “teach a lesson of subservience to illegitimate authority that is the antithesis of what institutions like Yale purport to stand for.”

Eric Foner, a leading American historian at Columbia, spoke out against the administration’s measures in a personal letter to President Levin. “As a longtime friend of Yale,” Foner began, “I am extremely distressed by the impasse that seems to have developed between the administration and the graduate teaching assistants.” Of particular concern, he noted, was the “developing atmosphere of anger and fear” at Yale, “sparked by threats of reprisal directed against teaching assistants.” He then concluded:

I wonder if you are fully aware of the damage this dispute is doing to Yale’s reputation as a citadel of academic freedom and educational leadership. Surely, a university is more than a business corporation and ought to adopt a more enlightened approach to dealing with its employees than is currently the norm in the business world. And in an era when Israelis and Palestinians, Bosnian Muslims and Bosnian Serbs, the British government and the IRA, have found it possible to engage in fruitful discussions after years of intransigent refusal to negotiate, it is difficult to understand why Yale’s administration cannot meet with representatives of the teaching assistants.

Foner’s letter played a critical role during the grad strike. The faculty took him seriously; his books on the Civil War and Reconstruction are required reading at Yale. But more important, Foner is a historian, and at the time, a particularly tense confrontation in the Yale history department was spinning out of control.

The incident involved teaching assistant Diana Paton, a British graduate student who was poised to write a dissertation on the transition in Jamaica from slavery to free labor, and historian David Brion Davis. A renowned scholar of slavery, Davis has written pathbreaking studies, earning him the Pulitzer Prize and a much-coveted slot as a frequent writer at the New York Review of Books. He represents the best traditions of humanistic learning, bringing to his work a moral sensitivity that few academics possess. Paton was his student and, that fall, his TA.

When Paton informed Davis that she intended to strike, he accused her of betraying him. Convinced that Davis would not support her academic career in the future—he had told her in an unrelated discussion a few weeks prior that he would never give his professional backing to any student who he believed had betrayed him—Paton nevertheless stood her ground. Davis reported her to the graduate school dean for disciplinary action and had his secretary instruct Paton not to appear at the final exam. In his letter to the dean, Davis wrote that Paton’s actions were “outrageous, irresponsible to the students…and totally disloyal.”

The day of the final, Paton showed up at the exam room. As she explains it, she wanted to demonstrate to Davis that she would not be intimidated by him, that she would not obey his orders. Davis, meanwhile, had learned of Paton’s plan to attend the exam and somehow concluded that she intended to steal the exams. So he had the door locked and two security guards stand beside it.

Though assertive, Paton is soft-spoken and reserved. She is also small. The thought of her rushing into the exam room, scooping up her students’ papers, engaging perhaps in a physical tussle with the delicate Davis, and then racing out the door—the whole idea is absurd. Yet Davis clearly believed it wasn’t absurd. What’s more, he convinced the administration that it wasn’t absurd, for it was the administration that had dispatched the security detail.

How this scenario could have been dreamed up by a historian with the nation’s most prestigious literary prizes under his belt—and with the full backing of one of the most renowned universities in the world—requires some explanation. Oddly enough, it is Davis himself who provides it.

Like something out of Hansel and Gretel, Davis left a set of clues, going back some forty years, to his paranoid behavior during the grade strike. In a pioneering 1960 article in the Mississippi Valley Historical Review, “Some Themes of Counter-Subversion: An Analysis of Anti-Masonic, Anti-Catholic, and Anti-Mormon Literature,” Davis set out to understand how dominant groups in nineteenth-century America were gripped by fears of disloyalty, treachery, subversion, and betrayal. Many Americans feared Catholics, Freemasons, and Mormons because, it was believed, they belonged to “a machine-like organization” that sought “to abolish free society” and “to overthrow divine principles of law and justice.” Members of these groups were dangerous because they professed an “unconditional loyalty to an autonomous body” like the pope. They took their marching orders from afar, and so were untrustworthy, duplicitous, and dangerous.

Davis was clearly disturbed by the authoritarian logic of the countersubversive, but that was in 1960 and he was writing about the nineteenth century. In 1995, confronting the rebellion of his own student, the logic made all the sense in the world. It didn’t matter that Paton was a longtime student of his, that she had many discussions with Davis about her academic work, and that he knew her well. As soon as she announced her commitment to the union’s course of action, she became a stranger, an alien marching on behalf of a foreign power.

Davis was hardly alone in voicing these concerns. Other respected members of the Yale faculty dipped into the same well of historical imagery. In January 1996, at the annual meeting of the American Historical Association, several historians presented a motion to censure Yale for its retaliation against the striking TAs. During the debate on the motion, Nancy Cott—one of the foremost scholars of women’s history in the country who was on the Yale faculty at the time but has since gone on to Harvard—defended the administration, pointing out that the TA union was affiliated with the Hotel Employees and Restaurant Employees International Union. Historians at the meeting say that Cott placed a special emphasis on the word “international.” The TAs, in other words, were carrying out the orders of union bosses in Washington. The graduate students did not care about their own colleagues, they were not loyal to their own. Not unlike the Masons and Catholics of old. It did not seem to faze Cott that she was speaking to an audience filled with labor historians, all of whom would have recognized these charges as classic antiunion rhetoric.

One of the reasons Cott embraced this vocabulary so unselfconsicously was that it was a virtual commonplace among the Yale faculty at the time. At a mid-December faculty meeting, which one professor compared to a Nuremberg rally, President Levin warned the faculty of the ties between the TAs and outside unions. The meeting was rife with lurid images of union heavies dictating how the faculty should run their classrooms. It never seemed to occur to these professors, who pride themselves on their independent judgment and intellectual perspicacity, that they were uncritically accepting some of the ugliest and most unfounded prejudices about unions, that they sounded more like the Jay Goulds and Andrew Carnegies of the late nineteenth century than the careful scholars and skeptical minds of the late twentieth. All they knew was their fear—that a conspiracy was afoot, that they were being forced to cede their authority to disagreeable powers outside of Yale.

Cott, Levin, and the rest of the faculty were also in the grip of a raging class anxiety, which English professor Annabel Patterson spelled out in a letter to the Modern Language Association. The TA union, Patterson wrote, “has always been a wing of Locals 34 and 35 [two other campus unions]…who draw their membership from the dining workers in colleges and other support staff.”

Why did Patterson single out cafeteria employees in her description of Locals 34 and 35? After all, these unions represent thousands of white- and blue-collar workers, everyone from skilled electricians and carpenters to research laboratory technicians, copy editors, and graphic designers. Perhaps it was that Patterson viewed dishwashers and plastic-gloved servers of institutional food as the most distasteful sector of the Yale workforce. Perhaps she thought that her audience would agree with her, and that a subtle appeal to their delicate, presumably shared, sensibilities would be enough to convince other professors that the TA union ought to be denied a role in the university.

The professor-student relationship was the critical link in a chain designed to keep dirty people out. What if the TAs and their friends in the dining halls decided that professors should wash the dishes and plumbers should teach the classes? Hadn’t that happened during the Cultural Revolution? Hadn’t the faculty themselves imagined such delightful utopias as young student radicals during the 1960s? Recognizing the TA union would only open Yale to a rougher, less refined element, and every professor, even the most liberal, had something at stake in keeping that element out.

In his article, Davis concluded with these sentences about the nineteenth-century countersubversive:

By focusing his attention on the imaginary threat of a secret conspiracy, he found an outlet for many irrational impulses, yet professed his loyalty to the ideals of equal rights and government by law. He paid lip service to the doctrine of laissez-faire individualism, but preached selfless dedication to a transcendent cause. The imposing threat of subversion justified a group loyalty and subordination of the individual that would otherwise have been unacceptable. In a rootless environment shaken by bewildering social change the nativist found unity and meaning by conspiring against imaginary conspiracies.

Though I don’t think Davis’s psychologizing holds much promise for understanding the Yale faculty’s response to the grade strike—the strike, after all, did pose a real threat to the faculty’s intuitions about both the place of graduate students in the university and the obligation of teachers; nor did the faculty seem, at least to me, to be on a desperate quest for meaning—he did manage to capture, long before the fact, the faculty’s fear that their tiered world of privileges and orders, so critical to the enterprise of civilization, was under assault. So did Davis envision the grotesque sense of fellowship that the faculty would derive from attacking their own students.

The faculty’s outsized rhetoric of loyalty and disloyalty, of intimacy (Dean [Richard] Brodhead called the parties to the conflict a “dysfunctional family”) betrayed, may have fit uneasily with their avowed professions of individualism and intellectual independence. But it did give them the opportunity to enjoy, at least for a moment, that strange euphoria—the thrilling release from dull routine, the delightful, newfound solidarity with fellow elites—that every reactionary from Edmund Burke to Augusto Pinochet has experienced upon confronting an organized challenge from below.

Paton’s relationship with Davis was ended. Luckily, she was able to find another advisor at Yale, Emilia Viotti da Costa, a Latin American historian who was also an expert on slavery. Da Costa, it turns out, had been a supporter of the student movement in Brazil some thirty years before and was persecuted by the military there. Forced to flee the country, she found in Yale a welcome refuge from repression.

I told you that in the coming days you’d be able to learn a lot about Erik’s ideas, if you wanted. Well, there are now 4 pieces at Jacobin by Erik’s former students and friends that, between them, tell you a great deal about his ideas, but also about how he was in the world. Vivek Chibber explains why Erik was a Marxist and, perhaps, more orthodoxly so than some people think. David Calnitsky gives you a sense of what Erik was like as a teacher. Elizabeth Wrigley-Field talks about how he conducted himself professionally around others. This story of David’s illustrates both his goofiness and his understanding that successful teaching depends, partly, on the right kind of relationship:

I attended an undergraduate lecture of his once, and at the beginning of class he reported that there was a student in his office hours who expressed being intimidated by him. He responded in class by showing childhood pictures – pictures of him at seven in a cowboy hat, pictures with his siblings.

And, having read that, this comment of Elizabeth’s won’t surprise you:

At the annual sociology meeting last August, when I knew he was sick but did not believe he would have so little time left, a few of us former students were talking about him. I commented that Erik was always exactly himself.

Then I thought about it a bit more, and I revised my remark. A lot of people — especially a lot of men — are “themselves” in a way that forces the people around them to conform: we all are supposed to contour ourselves around however they are. But Erik was the opposite of that: he was always really himself in a way that invited all of us to be ourselves, too.

And Michael Burawoy writes a long, beautiful, essay, combining an exposition of Erik’s ideas — his intellectual contribution — with the story of his life, and showing how well the two fit together.

And Here is a neat autobiographical essay with which Erik prefaced one of his later books. And, for that matter, here’s an enormous list of pdfs of his published writing.

I’ve wanted for a while to encourage people to buy John Crowley’s Totalitopia, which was published as part of Terry Bisson’s Outspoken Authors series at PM Press. It’s a great series of short books, each containing stories, essays and interviews. I also recommend Eleanor Arnason’s Mammoths of the Great Plains – if you liked what Le Guin did with anthropology, you will probably love Arnason -, and Kim Stanley Robinson’s The Lucky Strike). The e-books are now on sale, along with all the e-books at PM Press, for a dollar each (go to their website, pick the books you want and enter BUCK into the coupon field), except for those, like Robinson’s, which are free. I’ve spent the morning stocking up on Le Guin, Nalo Hopkinson, Ken MacLeod, Elizabeth Hand and others.

But Crowley again – Totalitopia has many good things. Perhaps the best is the lovely short story “This Is Our Town,” which approaches a 1950s Catholic childhood, with saints, miracles and mysteries, through the structure of genre, turning it into a self-contained universe which is both a fantasy and not, depending on whether you are looking from without (as Crowley now is), or within (as the child that Crowley was once did). His essay on the criminally underappreciated Paul Park is also very fine. The title essay, Totalitopia, is a non-fiction sequel to his novellas “Great Work of Time” and “In Blue,” talking about how every present generates its own impossible, contradictory futures, which quickly become antiquated, alien and lost.

[click to continue…]

I enjoyed this thread and was very proud of my own ability to stay out of it when the inevitable is-Tolkien-a-racist/fascist? arguments erupted. The thing is: I forgot to refute everyone who wrongly argued that Middle Earth isn’t a kind of Utopia. Then the thread closed. Damn.

I did start the job. In comments, I corrected cited this bit from “On Fairy-Stories”:

“And if we leave aside for a moment “fantasy,” I do not think that the reader or the maker of fairy-stories need even be ashamed of the “escape” of archaism: of preferring not dragons but horses, castles, sailing-ships, bows and arrows; not only elves, but knights and kings and priests. For it is after all possible for a rational man, after reflection (quite unconnected with fairy-story or romance), to arrive at the condemnation, implicit at least in the mere silence of “escapist” literature, of progressive things like factories, or the machine-guns and bombs that appear to be their most natural and inevitable, dare we say “inexorable,” products.

“The rawness and ugliness of modern European life”— that real life whose contact we should welcome —“is the sign of a biological inferiority, of an insufficient or false reaction to environment.” [Tolkien is quoting a social darwinist at this point] The maddest castle that ever came out of a giant’s bag in a wild Gaelic story is not only much less ugly than a robot-factory, it is also (to use a very modern phrase) “in a very real sense” a great deal more real. Why should we not escape from or condemn the “grim Assyrian” absurdity of top-hats, or the Morlockian horror of factories? They are condemned even by the writers of that most escapist form of all literature, stories of Science fiction. These prophets often foretell (and many seem to yearn for) a world like one big glass-roofed railway-station. But from them it is as a rule very hard to gather what men in such a world-town will do. They may abandon the “full Victorian panoply” for loose garments (with zip-fasteners), but will use this freedom mainly, it would appear, in order to play with mechanical toys in the soon-cloying game of moving at high speed. To judge by some of these tales they will still be as lustful, vengeful, and greedy as ever; and the ideals of their idealists hardly reach farther than the splendid notion of building more towns of the same sort on other planets. It is indeed an age of “improved means to deteriorated ends.” It is part of the essential malady of such days — producing the desire to escape, not indeed from life, but from our present time and self-made misery— that we are acutely conscious both of the ugliness of our works, and of their evil. So that to us evil and ugliness seem indissolubly allied. We find it difficult to conceive of evil and beauty together. The fear of the beautiful fay that ran through the elder ages almost eludes our grasp. Even more alarming: goodness is itself bereft of its proper beauty. In Faerie one can indeed conceive of an ogre who possesses a castle hideous as a nightmare (for the evil of the ogre wills it so), but one cannot conceive of a house built with a good purpose — an inn, a hostel for travellers, the hall of a virtuous and noble king—that is yet sickeningly ugly. At the present day it would be rash to hope to see one that was not — unless it was built before our time.”

Insofar as it seems to me quite obvious that the production of Tolkien’s own ‘fairy-stories’, from The Hobbit on, is motivated not just by the need for a place to store his made-up languages, but as a cry against the alleged ugliness of modernity – an attempt to wake people up that ugliness, by contrasting with an ideal alternative – it’s utopian. If News From Nowhere is utopian, then Tolkien is.

But, as I said, I forgot the clincher. Off To Be The Wizard is a pretty funny novel. Plotspoilers under the fold.

I’m lecturing about Utopian/Dystopian SF this week. I’ve lectured on this before but I’m looking to up my game, so I’m open to suggestions. Lots of writings on or around this subject, as well as stories to choose from. We had a whole book event about Real Utopias here at CT. What critical writings in this vicinity do you find particularly insightful/interesting?

Yesterday I was browsing through The Cambridge Companion to Utopian Literature, seeking inspiration/information. From the introduction to Kenneth M. Roemer, “Paradise Transformed: Varieties of 19th Century Utopias”:

[click to continue…]

In Why Coase’s Penguin didn’t fly, Henry follows up his response to Cory’s Walkaway by claiming that peer production failed, and arguing that the reason I failed to predict its failure is that I ignored the role of power in my analysis.

Tl;dr: evidence on the success/failure of peer production is much less clear than that, but is not my issue here. Coase’s Penguin and Sharing Nicely were pieces aimed to be internal to mainstream economics to establish the feasibility of social sharing and cooperation as a major modality of production within certain technological conditions; conditions that obtain now. It was not a claim about the necessary success of such practices. Those two economist-oriented papers were embedded in a line of work that put power and struggle over whether this feasible set of practices would in fact come to pass at the center of my analysis. Power in social relations, and how it shapes and is shaped by battles over technical (open/closed), institutional (commons/property), ideological (cooperation/competition//homo economicus/homo socialis), and organizational (peer production & social production vs. hierarchies/markets) systems has been the central subject of my work. The detailed support for this claim is unfortunately highly self-referential, trying to keep myself honest that I am not merely engaged in ex-post self-justification. Apologies. [click to continue…]

This talk by Maciej Ceglowski (who y’all should be reading if you aren’t already) is really good on silly claims by philosophers about AI, and how they feed into Silicon Valley mythology. But there’s one claim that seems to me to be flat out wrong:

We need better scifi! And like so many things, we already have the technology. This is Stanislaw Lem, the great Polish scifi author. English-language scifi is terrible, but in the Eastern bloc we have the goods, and we need to make sure it’s exported properly. It’s already been translated well into English, it just needs to be better distributed. What sets authors like Lem and the Strugatsky brothers above their Western counterparts is that these are people who grew up in difficult circumstances, experienced the war, and then lived in a totalitarian society where they had to express their ideas obliquely through writing. They have an actual understanding of human experience and the limits of Utopian thinking that is nearly absent from the west.There are some notable exceptions—Stanley Kubrick was able to do it—but it’s exceptionally rare to find American or British scifi that has any kind of humility about what we as a species can do with technology.

He’s not wrong on the delights of Lem and the Strugastky brothers, heaven forbid! (I had a great conversation with a Russian woman some months ago about the Strugatskys – she hadn’t realized that Roadside Picnic had been translated into English, much less that it had given rise to its own micro-genre). But wrong on US and (especially) British SF. It seems to me that fiction on the limits of utopian thinking and the need for humility about technology is vast. Plausible genealogies for sf stretch back, after all, to Shelley’s utopian-science-gone-wrong Frankenstein (rather than Hugo Gernsback. Some examples that leap immediately to mind:

Ursula Le Guin and the whole literature of ambiguous utopias that she helped bring into being with The Dispossessed – see e.g. Ada Palmer, Kim Stanley Robinson’s Mars series &c.

J.G Ballard, passim

Philip K. Dick (passim, but if there’s a better description of how the Internet of Things is likely to work out than the door demanding money to open in Ubik I haven’t read it).

Octavia Butler’s Parable books. Also, Jack Womack’s Dryco books (this interview with Womack could have been written yesterday).

William Gibson (passim, but especially “The Gernsback Continuum” and his most recent work. “The street finds its own uses for things” is a specifically and deliberately anti-tech-utopian aesthetic).

M. John Harrison – Signs of Life and the Kefahuchi Tract books.

Paul McAuley (most particularly Fairyland – also his most recent Something Coming Through and Into Everywhere, which mine the Roadside Picnic vein of brain-altering alien trash in some extremely interesting ways).

Robert Charles Wilson, Spin. The best SF book I’ve ever read on how small human beings and all their inventions are from a cosmological perspective.

Maureen McHugh’s China Mountain Zhang.

Also, if it’s not cheating, Francis Spufford’s Red Plenty (if Kim Stanley Robinson describes it as a novel in the SF tradition, who am I to disagree, especially since it is all about the limits of capitalism as well as communism).

I’m sure there’s plenty of other writers I could mention (feel free to say who they are in comments). I’d also love to see more translated SF from the former Warsaw Pact countries, if it is nearly as good as the Strugatskys material which has appeared. Still, I think that Ceglowski’s claim is wrong. The people I mention above aren’t peripheral to the genre under any reasonable definition, and they all write books and stories that do what Ceglowski thinks is only very rarely done. He’s got some fun reading ahead of him.

I was sweeping the sand in the palaestra one morning when Sokrates came along with Apollo, deep in talk. “Ah, Crocus,” Sokrates said when he caught sight of me. “Just the person we need to add to our conversation. Ruthanna believes that leaders should have varied experience, that this would make them more excellent. What do you think?”

“Plato says in the Republic that everyone should be immersed in one thing, that people have only one excellence,” I said. “But this has always seemed strange to me. Workers, by our very nature, are intended to work. I am a philosopher, but I am also a robot, and I have robot excellence. In addition, I have long held that there are forms of art that are more akin to philosophy than to craft, though they naturally require skill in crafting. I further believe that it does no harm to engage in other tasks, such as this raking sand, which leaves the mind free to contemplate. But I had not considered that diversity of work might actually be a benefit.” [click to continue…]

In this post I’ll discuss some ways in which Walton’s Thessaly series is transformative and some ways in which it’s feminist, and some thoughts on how those choices reinforce each other.

To start with, clearly, Thessaly is transformative in that it concentrates on reusing and commenting on a text someone else made. As Walton [says](http://www.jowaltonbooks.com/books/the-just-city/):

> Writing about Plato’s Republic being tried seems to me an idea that is so obvious everyone should have had it, that it should be a subgenre, there should be versions written by Diderot and George Eliot and Orwell and H. Beam Piper and Octavia Butler.

I’m currently [obsessed](http://www.tor.com/2015/12/21/the-uses-of-history-in-hamilton-an-american-musical/) with *Hamilton: An American Musical* which, like Thessaly, takes old text — often taught in history or philosophy or political science classes — and infuses it with emotion and suspense. But, where *Hamilton* only has a few songs focusing on the process of group decision-making and problems that crop up in the implementation, Walton pays consistent attention to those details. This approach also shows up in Walton’s [“Relentlessly Mundane”](http://www.strangehorizons.com/2000/20001023/relentlessly_mundane.shtml), which you can read as a Narnia fanfic with the serial numbers very rubbed off, or as a general commentary on YA portal fantasies. Paying attention to the concrete details within utopias and after quests, Walton un-deletes the deleted scenes from other stories. [click to continue…]

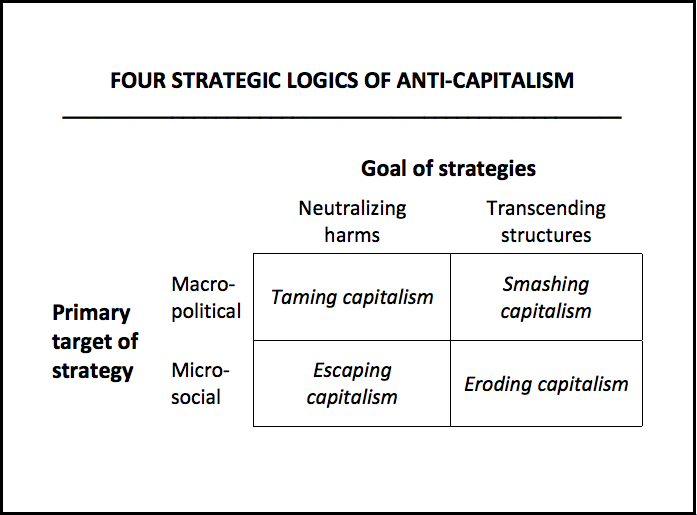

Our friend Erik Olin Wright has s long essay on How to be an Anti-Capitalist at Jacobin. Read the whole thing here.

An excerpt:

The Four Types of Anticapitalism

Capitalism breeds anticapitalists.

Sometimes resistance to capitalism is crystallized in coherent ideologies that offer both systematic diagnoses of the source of harms and clear prescriptions about how to eliminate them. In other circumstances anticapitalism is submerged within motivations that on the surface have little to do with capitalism, such as religious beliefs that lead people to reject modernity and seek refuge in isolated communities. But always, wherever capitalism exists, there is discontent and resistance in one form or other.

Historically, anticapitalism has been animated by four different logics of resistance: smashing capitalism, taming capitalism, escaping capitalism, and eroding capitalism.

These logics often coexist and intermingle, but they each constitute a distinct way of responding to the harms of capitalism. These four forms of anticapitalism can be thought of as varying along two dimensions.

One concerns the goal of anticapitalist strategies — transcending the structures of capitalism or simply neutralizing the worst harms of capitalism — while the other dimension concerns the primary target of the strategies — whether the target is the state and other institutions at the macro-level of the system, or the economic activities of individuals, organizations, and communities at the micro-level.

Taking these two dimensions together gives us the typology below.

A while ago, I listened to a fascinating talk by Erik Olin Wright about Envisioning Real Utopias, on which we held a book event a while back.[^1] He mentioned the Port Huron Statement, published by Students for a Democratic Society in 1962. I looked it up, and was struck by the fact that it envisaged, and welcomed, the political realignment later implemented by Richard Nixon as the Southern Strategy, and which still dominates US politics.

A most alarming fact is that few, if any, politicians are calling for changes in these conditions. Only a handful even are calling on the President to “live up to” platform pledges; no one is demanding structural changes, such as the shuttling of Southern Democrats out of the Democratic Party…. super-patriotic groups have become a politically influential force within the Republican Party, at a national level through Senator Goldwater, and at a local level through their important social and economic roles. Their political views are defined generally as the opposite of the supposed views of communists: complete individual freedom in the economic sphere, non-participation by the government in the machinery of production. But actually “anticommunism” becomes an umbrella by which to protest liberalism, internationalism, welfarism, the active civil rights and labor movements. It is to the disgrace of the United States that such a movement should become a prominent kind of public participation in the modern world — but, ironically, it is somewhat to the interests of the United States that such a movement should be a public constituency pointed toward realignment of the political parties, demanding a conservative Republican Party in the South and an exclusion of the “leftist” elements of the national GOP.

I don’t suppose the SDS activists thought that the combination of the Goldwater right and the Southern Democrats would form a majority coalition strong enough to dominate US politics for decades. Still it’s far from obvious that they were wrong in wishing for the emergence of a clear partisan division to replace the coalition politics of the time.[^2]

Any assessment of the realignment is complicated by the shift to the right that took place throughout the developed from the 1970s onwards. The fact that this shift seems to be going into reverse in the US.[^3], while it is accelerating in Europe, may be in part the product of the great realignment. Oddly enough, precisely because partisan politics is so new in the US, the Dems seem to be more willing to engage in it than their Social Democratic counterparts in Europe (of course, they’ve been schooled in it by the Repubs for twenty years or so). And while the objective position of the Dems is still well to the right of European SocDems, they seem to be breaking with neoliberal ideas like the Grand Bargain at precisely the time the SocDems are (for the most part) capitulating to austerity.

[^1]: We seem to be missing the link on this, but here’s my opening contribution.

[^2]: BTW, it seems bizarre to me, and to other non-US people I’ve talked to that the acryonym GOP is used to describe the Repubs, even by a group as hostile as the SDS. There’s no corresponding acronym for the Democrats – it would seem that DP and RP or just D’s and R’s would serve much better. Any thoughts on this?

[^3]: As evidenced both by the renewed electoral success of the Democrats, and more tenuously, by a shift away from the idea of a market liberal “Grand Bargain” and towards a reassertion of support for the institutions of the New Deal (minus the accommodation with Southern racism).

In a recent post I remarked that MLK is a figure well worth stealing. And NR obliges me with the first sentence of their anniversary editorial. “The civil-rights revolution, like the American revolution, was in a crucial sense conservative.” They do admit a few paragraphs on that, “Too many conservatives and libertarians, including the editors of this magazine, missed all of this at the time.” And then manage to wreck it all again with the next sentence: “They worried about the effects of the civil-rights movement on federalism and limited government. Those principles weren’t wrong, exactly; they were tragically misapplied, given the moral and historical context.” No look into the question of how such a misapplication transpired, since that would not produce gratifying results. After all, if we are talking about what actually worried people, then plainly federalism and limited government were more pretext than motive. The tragedy is that so many people wanted to do the wrong thing, for bad reasons. But they couldn’t say ‘Boo justice!’ So they said stuff about … federalism. There is obviously no point to conservative’s revisiting how they got things wrong without bothering to consider how they got things wrong. But let’s be positive about it. “It is a mark of the success of King’s movement that almost all Americans can now see its necessity.” Yay justice!

I’m sitting down to read Kwame Anthony Appiah’s book, The Honor Code: How Moral Revolutions Happen [amazon]. I’m planning to agree with it, but the framing is odd. [click to continue…]

I’ve posted about this before – here and here and here and here. What film is that? The H. G. Wells-scripted/William Cameron Menzies-directed Things To Come (1936), of course. Everyone should have a hobby.

The Criterion Collection just released a new, restored version on Blu-Ray. Oh joy!

Here are some stills – all crisp and clear for the first time! [click to continue…]

This is, in a silly way, a footnote to my previous Kevin Williamson post, but, more seriously, to my contribution to our Erik Olin Wright event. In my post on Wright I remarked that, in a sense, he’s pushing against an open door: he wants Americans, who think ‘socialism’ is a dirty word, to be more open to utopian thinking. The problem, I pointed out, is that thinking ‘socialism’ is a dirty word is positively, not negatively, correlated with utopianism, because conservatives are, typically, very utopian, especially in their rhetoric – more so than socialists these days; certainly more so than liberals. Wright responded that his project “is not mainly directed at ideologically committed Conservatives whose core values support the power and privilege of dominant classes. The core audience is people who are loosely sympathetic to some mix of liberal egalitarian, radical democratic and communitarian ideals.” [click to continue…]