The news that NICE has put acupuncture and chiropractic on the list of approved therapies for non-specific lower back pain has led to about the reactions you’d expect – back-slapping and high-fiving from the crystals and “life force” crowd, agonised complaining from the professional skeptics. But it’s actually a sign of something that ought to make us worry, not much but at least a little bit, about the way in which we’re doing medical science in this country.

[click to continue…]

{ 79 comments }

The economic crisis has, as we’ve been discussing, raised a lot of interest in Keynesian economics, but so far it’s been based more on the obvious bankruptcy of alternatives than on successful examples of Keynesian fiscal stimulus. Although there were some big financial bailouts late last year, few countries engaged in large-scale fiscal stimulus before the first few months of this year (Obama’s package was passed in February, and is only now being implemented, so we can’t expect to see evidence of impacts on GDP until late this year).

Australia went early and hard with a substantial cash handout to households in December 2008, followed by another round of cash stimulus delivered a month or two ago, and then a large-scale infrastructure program. The national accounts for the March quarter (which should include the effects of the first round of stimulus) have just come out, and show growth of 0.4 per cent, compared to a 0.6 per cent contraction in the December 2008 quarter[1]

On the face of it, this is a big success for Keynesian fiscal policy. And, there’s pretty general agreement that, despite some qualifications and plenty of concerns about the future, the prima facie interpretation is the correct one.

{ 18 comments }

I just wanted to post a quick note about one of our upcoming guest bloggers so readers who’re not familiar with her work can read up on it. Michèle Lamont is most recently author of How Professors Think, a book that’s already inspired discussions here at CT. Other books of hers you may have come across (or if not then should check out) include The Dignity of Working Men and Money, Morals and Manners. Also, her co-edited volume (with Marcel Fournier) on Cultivating Differences: Symbolic Boundaries and the Making of Inequality is standard text on Sociology of Culture syllabi. And then there are her many articles. This is just a heads up.

{ 2 comments }

Via Laura, I see this kitchen table math post on Richard Elmore’s paper on “high performing” schools. Elmore observes that so-called high performing schools in affluent communities that he works in often seem very similar to low-performing schools in low-income communities, and very unlike successful schools in low-income communities. Here’s Elmore on successful high-performing schools:

{ 62 comments }

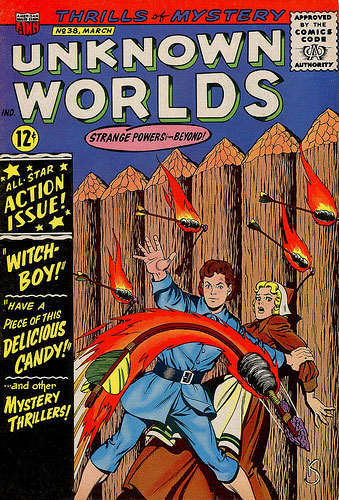

It’s no secret that I’m a Klarion the Witch Boy fan. Which is why I was so amazed to see this on Flickr today. Kirby’s Klarion dates from 1973. But here is a pilgrim “witch boy” as early as 1965! “Thrills of mystery, Unknown worlds, strange powers – beyond” indeed! This could change everything! I feel like those scientists who dug up the Ida fossil. (Because I’m much less ambitious, obviously.)

{ 10 comments }

“Matthew Yglesias”:http://yglesias.thinkprogress.org/archives/2009/06/prestige-cross-pollination.php does Martin Feldstein a serious injustice.

Feldstein’s characterization of the bill isn’t really correct and some of his economic analysis is debatable. But beyond that, the key point on which Feldstein’s argument turns actually has nothing whatsoever to do with economics. … Feldstein’s hypothesis … is clearly a proposition about _international relations_ … Presumably the reason the Post is interested in Feldstein is his expertise in economics. So there’s no reason for them to be running an op-ed whose key contention has nothing to do with economics.

Matt is clearly unaware of Feldstein’s distinguished record as a theorist of international relations (this may not be as distinguished as his research record on “the relationship between Social Security and savings”:http://www.monthlyreview.org/nftae02.htm, but you can only do what you can do). Feldstein is particularly famous (well, famous is one way of putting it), for his suggestion in a 1997 “Foreign Affairs article”:http://www.nber.org/feldstein/fa1197.html that the introduction of the euro might lead to a civil war that would tear Europe apart.

War within Europe itself would be abhorrent but not impossible. The conflicts over economic policies and interference with national sovereignty could reinforce long-standing animosities based on history, nationality, and religion. Germany’s assertion that it needs to be contained in a larger European political entity is itself a warning. Would such a structure contain Germany, or tempt it to exercise hegemonic leadership?

A critical feature of the EU in general and EMU in particular is that there is no legitimate way for a member to withdraw. This is a marriage made in heaven that must last forever. But if countries discover that the shift to a single currency is hurting their economies and that the new political arrangements also are not to their liking, some of them will want to leave. The majority may not look kindly on secession, either out of economic self-interest or a more general concern about the stability of the entire union. The American experience with the secession of the South may contain some lessons about the danger of a treaty or constitution that has no exits.

The carpers and the hurlers on the ditch might complain that Jean-Yves Reb hasn’t reached for his rifle in the intervening ten years, and doesn’t look like he’s going to anytime in the foreseeable future. But that would be to miss the point that Feldstein’s contribution spurred “much”:http://users.ox.ac.uk/~ssfc0041/federalideals.pdf “spirited”:https://segue.middlebury.edu/repository/viewfile/polyphony-repository___repository_id/edu.middlebury.segue.sites_repository/polyphony-repository___asset_id/2089508/polyphony-repository___record_id/2089509/polyphony-repository___file_name/Amy_Verdun.pdf “discussion”:http://mq.dukejournals.org/cgi/reprint/12/4/33.pdf among international relations scholars, and specialists on the European Union (most of it not very complimentary to Professor Feldstein, but again, you can only do what you can do).

{ 38 comments }

One could debate and dispute whether implementing a Basic Income Grant would be a good idea in affluent post-industrial societies, as we did (“here”:https://crookedtimber.org/2007/02/28/redesigning-distribution/ and “here”:https://crookedtimber.org/2007/07/10/should-feminists-support-basic-income/ and “here”:https://crookedtimber.org/2009/02/02/feminism-and-basic-income-revisited/) at CT before. Yet for developing societies with serious problems of persistent poverty, it seems to me like a very good idea indeed. One could add as a (desirable) condition that such a society should be able to internally generate the money to fund such a BIG (that is, there must be a big enough section of rich or middle class people whose consumption or income can be taxed). The idea may work wonderfully in countries like South Africa for example. If you give poor South Africans a relatively tiny BIG, they are not given welfare payouts that enable them to sit back and rest (as the critics may have it), but rather people are given some very basic means to take their lives in their own hands: money for food, for basic health care, for school fees, for a roof above their head, and perhaps to set up a small business. No more begging for food needed. The amounts can be tiny and may seem like pocketmoney to people in the global North, but as we know from the relative success of microcredits, poor people can change their lives (and those of their children) when they have small amounts of money.

There is now empirical evidence supporting this line of reasoning, coming from Namibia, where in 2004 “a coalition”:http://www.bignam.org/ of churches, trade unions, NGOs and AIDS organisations decided to run a pilot project to figure out what a small BIG would do to the lives of the extreme poor.

{ 27 comments }

Yes, it is true! Visit the official book site. You can view the whole thing via Issuu.com, which has a very nice Flash-based reader: minimal and elegant but full-featured. And/or download the PDF for offline reading.

Want to see a neat trick? I can embed the book, like so.

Then you just click to turn the page (illegible at this size) or click to open and read in full-screen mode. It’s a very nice viewer they’ve got. Or I could make the embed open on a particular page, so when I’m blogging about a passage while teaching, I can just point the kids to the page in question. Or open the book itself onscreen in class and zoom so it’s readable. Neat, I call it.

The full book title (some would say: over-full): Reason and Persuasion, Three Dialogues by Plato: Euthyphro, Meno and Republic book I, with commentary and illustrations by John Holbo and translations by Belle Waring. It will be out in print by mid-August. The version that is up right now is actually the final draft – so far as I can tell. But I still have a week-and-a-bit to catch any last typos or mistakes. (I have a terrible suspicion that the Stephanus pages may have shifted a bit during the last edit. Gotta check that. How tedious, but oh-so-necessary.) I hope there aren’t any major problems with the book still, at this point. But if there are – well, I will do my best to make needed changes. So if you would like to volunteer your services as proofreader/last minute reviewer/critic, you are most welcome.

Not pre-publication peer-review. Not old-fashioned post-publication review. Perinatal peer-review. (Socrates always said he was a midwife. So I assume he would approve.)

The book is published by Pearson Asia (that’s a story in itself) and will be available in paperback by mid-August. They’ve been bringing out nice, inexpensive draft versions for my students in Singapore (that’s why I have an Asian publisher.) For this first general release I insisted on extending the deal I had insisted on for my own classroom use: I reserve the e-rights and so have a free hand to try manner of cool free e-stuff. I’m hoping one reward for my virtuous ways will be that some folks will want to adopt the book for classroom use. (Free e-availability is a big pedagogic bonus, I think.) And will then see to it that copies of the book are in school bookstores, so Pearson (and I) get paid a little. That seems fair.

OK, that’s all for now. If you want to talk Plato, please come on over to the book site. (And link! Please link! And help me edit the book, last minute, if you wouldn’t mind.) But it might be fun to chat about e-publishing in academia in this thread. If you are inclined. Doesn’t this sort of thing make a lot of sense. whatever you think of my particular book? I say it does.

{ 57 comments }

I’m working on a bunch of essays, book chapters and maybe even a book or two in response to the global financial crisis, making the general point that the sudden collapse of the neoliberal order has found social democrats unprepared for the shift from a long defensive struggle to the opportunity (and need!) to develop a progressive response to the crisis. As obvious examples, it’s necessary to reconstruct the global financial system and to ensure that the burden of the debts that are building up so rapidly is not borne by the poor, who did nothing to create the crisis. This piece (PDF) is an example of what I’m thinking.

I have plenty of ideas about policy (though of course I’m always interested in new ones). But, I don’t have much of a feeling for the political strategies that are needed, so I thought I would try the crowdsourcing thing, which has worked pretty well for me in the past.

{ 63 comments }

I wasn’t all that surprised that Bryan Caplan didn’t like my interpretation of our bet on EU and US unemployment rates, which was that the combined rates of unemployment and incarceration in the US would exceed those in the EU over the next ten years. I was, however, surprised by the vehemence with which libertarian-inclined* commenters here and at my blog objected to this interpretation.

A string of them echoed Caplan’s argument that

From a labor market perspective, though, Quiggin’s incarceration adjustment would only make sense if you thought that most or all of the people in jail would be unemployed if they were released.

Caplan has missed my main point. I’m not suggesting that incarceration is disguised unemployment (though obviously it reduces measured unemployment). Rather, I’m saying that, like unemployment, incarceration should be regarded as a (bad) labor market outcome. If you want to evaluate the performance of the labor market, you need to look at both.

{ 100 comments }

This is a follow-up to the distinctly non-sober but not wholly unuseful thread attached to my post on the Boston Review piece on Malhotra and Margalit’s survey research on anti-semitism and the financial crisis. The authors have asked for a chance to explain themselves, and their methodology, which has come in for a lot of criticism of an unavoidably speculative sort in comments to my post. Let’s hope this clears a few things up. Let’s try to be civil, shall we? The following is, obviously, not by me but by Malhotra and Margalit. And not edited by me in any way. – John Holbo

We are glad that our article generated thoughtful discussion, and we would be happy to address some of the questions people raised in the comments section. If our responses do not specifically address your particular comment, apologies in advance. Our goal here is to touch on some of the main issues. [click to continue…]

{ 97 comments }

Hey, you know those psychedelic bio text images I posted about? Well, someone took an interest in the post and the images and went and did a bit of research on the textbook itself: [click to continue…]

{ 5 comments }

This “common trope”:http://politics.theatlantic.com/2009/05/obamas_new_capitalism.php (this particular example is taken from Marc Ambinder) in discussions over the auto industry seems to me to be based on faulty logic.

Bondholders are kicking and screaming, but it appears as if General Motors Corp. is headed for an orderly bankruptcy, and the Obama administration is about to be handed the keys to a venerable corporate institution. Again. And again, the administration seems to be rewriting the rules of capitalism to fashion a deal to its liking. Purists — and virtually every academic economist one happens to encounter — wonder what happened to the once inviolate principle of rewarding risk-takers. Unsecured creditors will get less of a stake in the new GM than its employees, and you can forget about poor unadorned stockholders.

As I understand it (commenters may have different rationales), the idea that people should be rewarded for taking risk is that people making risky investments should receive higher returns on those investments in order to compensate for those risks. In capitalist systems, you often see the argument being made that the owners of capital should receive high returns on their capital to compensate them for the risk that the companies they have invested in go bust. But this does _not_ mean that capital owners should have first bite at the cherry if the company _does_ go bust. The risk that the company goes bust – and that capital owners lose their shirts in the process – is precisely the risk that they are supposedly already been compensated for. In other words, you can’t have it both ways – getting special compensation for the risk that you will lose your money if the firm goes bust implies that you shouldn’t get special compensation in the event that the company does go bust. Or you wouldn’t have been taking any risks in the first place.

So I simply don’t see that this cod-Schumpeterian argument makes any sense. A real Schumpeterian, I suspect, would be saying that no-one should get compensated at all, either capitalists or workers, and that the companies should be allowed to go bust (but that of course is a quite different argument). You could perhaps make a case on normative grounds that people who took a higher risk should get a bigger share of whatever is left. But you would have to take account of the fact that it isn’t only owners of capitalists who take these risks. Workers in GM have made risky investments themselves – in specialized skills that are difficult to sell on the market – and these risks were arguably greater than the ones taken by capitalists (bankers and investors, for all their travails, are surely doing better than unemployed auto workers).

{ 46 comments }

But first: why aren’t you reading more Squid and Owl. It’s cheap and morally improving. For example, last night’s exciting episode:

What we learn from this is, for example, that we should read comics. But which? (you gesticulate approximately and therefore helplessly?) Some are good, but some are bad. I have recently enjoyed the Eisner-nominated The Amazing Remarkable Monsieur Leotard [amazon], by Eddie Campbell, who has a blog. Since First Second has a generous preview online, you could sample before buying.

And, under the fold, I’ll just tuck a few circus-related images I’ve stumbled on on Flickr: [click to continue…]

{ 4 comments }

Bryan Caplan and I have now agreed on the settlement conditions for a bet on US_EU jobless rates while also agreeing to differ on the interpretation. The stake is $US100 and the agreed criterion is that, for Bryan to win, the average Eurostat harmonised unemployment rate for the EU-15 over the period 2009-18 inclusive should exceed that for the US by at least 1.5 percentage points.

Since the implied difference in the proportion of the population who are unemployed is almost exactly equal* to the difference in the proportion of the population who are incarcerated, I interpret my side the bet as follows

Averaged over 2009-18, the sum of incarceration and unemployment rates in the US will exceed that in the EU-15

Caplan wants to leave incarceration out of the discussion and focus only in unemployment. Since we’re agreed on how to settle the bet, there’s no problem with differing on how to interpret the result.

{ 26 comments }