What with all the kerfuffle about the NYT article on Ivy League women and their labor market / parenting plans, I took a look at some BLS data on long-term trends in earnings patterns within families, and in mothers’ labor force participation. Here are a couple of figures I created that capture some of what’s been happening in these areas over the past thirty-odd years.

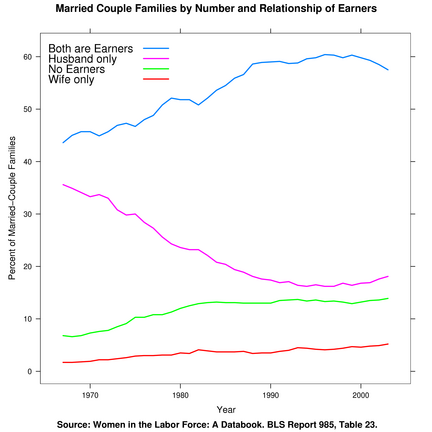

The first figure shows trends in earning patterns within families. (You can get it as a PDF file.) Here you can see that even in 1967, when the series starts, families where the Husband was the only earner were already a minority of all families. By the 1990s, there were almost as many families with no earners as families where only the Husband was working. The percentage of families where only the Wife was working rose from 1.7 to 5.2 percent from 1967 to 2003. The percentage of families where both the husband and wife were working peaked in 1999 (at just over 60 percent) and has fallen slightly since then. Note that this figure doesn’t tell you how earning patterns change once families have children, just the absolute numbers of each type, whether they have children or not.

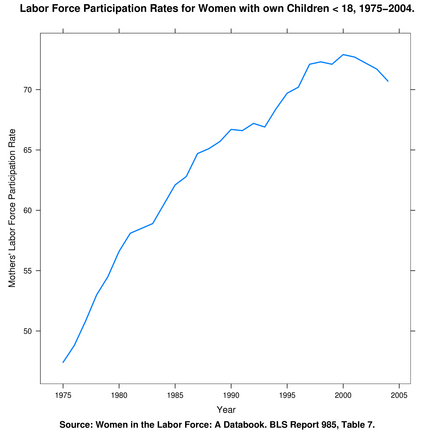

The next figure shows trends in the labor force participation rate of mothers with children under the age of 18. (You can get it as a PDF file.) Here the trend (obviously) is one of consistent growth — though again, even in 1975 47 percent of mothers (with children under 18) were in the workforce. Their participation rates peak in 2000, at just shy of 73 percent. By 2004 the rate had dropped two percentage points to 70.7 percent. Note that this figure doesn’t tell you how participation rates vary by household income.

The timing of the declines in both dual-earner families and mothers’ labor force participation look to me as though they are driven by sensitivity to prevailing labor market conditions rather than any widespread change in attitudes to work and motherhood. But what do I know? At any rate, it’s good to have a resource like the BLS to hand, if only to add a bit of context to your survey of 60-odd Yale and Harvard students.

{ 2 trackbacks }

{ 21 comments }

sd 09.22.05 at 1:41 am

“The timing of the declines in both dual-earner families and mothers’ labor force participation look to me as though they are driven by sensitivity to prevailing labor market conditions rather than any widespread change in attitudes to work and motherhood.”

This would indeed be a good hypothesis for the post-2001 phenomena if we could find any indication that similar phenomena coincided with earlier downturns in the economy. Eyeballing the graphs it looks like there was another significant downturn in dual-earner families in about 1980-1982, though it doesn’t look like the magnitude of that downturn matches that of the current downturn. However there is simply no precedent in the data here for the recent dropoff in mothers’labor force participation – the magnitude is huge compared to the other dropoffs in the period. And it looks like the dropoff began in 2000 when the labor market was still red hot.

It just doesn’t look like the recent trends are driven by softness in the labor markets.

M. Gordon 09.22.05 at 1:45 am

Maybe I’m misunderstanding your point, but it looks to me like the most striking trend is the complementarity of the “husband only” and “both earners” trends. That these are essentially mirror images, both with extrema at roughly the same point, suggests to me that, in fact, families are transferring from one group to the other, i.e., that families where both parents were earners are now becoming husband-only-earner families. This seems to support the trend cited by the NYT article.

Martin James 09.22.05 at 1:55 am

Kieran,

Well, we all knew that the last 25 years of freedom and equality have put considerably more women with kids into paid employment.

We obviously have no institutional problem getting women to work in the economy.

So why the kerfuffle about an article about a few smart women saying they want to buck the system and stay home?

Isn’t the first rule of thumb in sociology still “Some do, some don’t.”

bad Jim 09.22.05 at 2:46 am

The point of the first graph is that the median family workforce has two members. The husbands-only model is converging on the public assistance and wife-only trends. Working women might find some bitter satisfaction there, if not much hope.

We need some information on the unwedded to draw some conclusions, but it seems clear that nowadays most households find two paychecks a necessity. It might have something to do with the ideal of home ownership.

nik 09.22.05 at 2:49 am

This is an obvious point: but someone’s got to make it. The first figure relates to married couple families. There have obviously been substantial changes in both the proportion and ages of married couples families over the last 30-years, and in the number of married couple families without children. Changes can be driven by this and in the number of single mothers.

As the population of married couples ages, you’re are going to get changes in the ratio of men to women in employment driven purely by differing legal retirement ages. There will also be an effect on the proportions occuring in various groups (does no earners include retires?).

There’s a substantial demographic element in the background. Labor market conditions and changes in attitudes to work and motherhood aren’t the only thing going on.

John Quiggin 09.22.05 at 4:11 am

A minor clarification. The graph is titled “employment rate” but the Y-axis is labelled “participation rate”, which includes the unemployed. Looking at the original data it seems to be the participation rate that is graphed. The employment rate would show the same pattern but more marked, since the unemployment rate for mothers of children under 18 hit an all-time (at least for the date period) low in 2000.

Presumably welfare reform is a significant factor in the sharp rise in mothers’ employment in the late 90s, which makes the subsequent decline all the more worrying. There doesn’t seem to be much data on the post-2000 impact of welfare reform in a weak labour market.

nik 09.22.05 at 4:54 am

One other point. The most significant New Labour welfare change is the Child Tax Credit scheme (nee the Working Families Tax Credit) announced in 1998. This involves giving money to people with children, it’s linked to household income and targeted mainly at households with low income. But also including quite reasonable sums for quite rich families.

This has had a substantial effect on many families circumstances (and lifted lots of children out of poverty), I wouldn’t discount an effect upon workplace participation. It could have raised the income of some families to a level where mothers could take time out the workforce without a substantial effect from lost income.

Heather Boushey 09.22.05 at 7:55 am

Regarding the question of labor market slackness, the most recent recession has looked very different from prior recessions. First, the overall employment rate is still below the pre-recession peak, nearly four years after the recession began, which in historical terms is exceptionally long. Second, women’s employment fell more during the early 2000s recession than it had in prior recessions. (It is still the case that men’s employment fell more than women’s, but the women are catching up.) When you compare the drop in employment rates for prime-age women with and without children, you see that mothers’s employment decline is only slightly larger than non-mothers — from 1999 to 2003 a drop of 4.4 percentage points for mothers and 3.2 for non-mothers. Men’s employment is still 1.6 percentage points where it was in 2000. (We have a paper on this at http://www.cepr.net; all data is from BLS.)

Thus, when wondering whether or not declining employment among women is “family-driven” or “slack labor market-driven”, the evidence is that the recession was harder on women than the previous recessions, but it was even harder on men. Maybe mothers can’t find work and have thus “chosen” to stay at home — or maybe the dads are providing the child care?

The thing that really strikes me about the NYT story by Louise Story is that it does not recognize just how difficult it looks to be a dual-earner family in your twenties with kids. Young, ambitious women know that the reality is that they have two choices: advance or see their kids, spouse, friends. This isn’t really a choice.

Kieran Healy 09.22.05 at 8:36 am

The graph is titled “employment rate†but the Y-axis is labelled “participation rate

Whoops — yes, as you say, it’s the participation rate that’s being shown here. It was a bit late at night when I did this: I’ll relabel the graph so the title is right.

Kieran Healy 09.22.05 at 9:05 am

On reflection (i.e., next morning) I think the labor market slackness comment is probably off the mark. By the way, I didn’t have a particular axe to grind when going to look up these trends — I just wanted to see what the typical arrangements had been over a long period.

Tad Brennan 09.22.05 at 9:31 am

small point on the title of this post–

“Family earning trends” sounds to this (non-economist, non-sociologist) reader’s ear as though it will tell me about changes in dollar-values (earnings): e.g., did household income go up or down; did households with husband-only employed see faster growth in household income than two-job couples, etc.

I really don’t see much in this post about “earning trends” in the sense of “trends in what people earn, sc. dollars”. So is there a different sense of “earning” in your discipline in which it means “participation in the labor force”? Or should this post be titled, e.g. “Some data on labor participation trends” or the like?

tina 09.22.05 at 9:33 am

oo! these graphs will be great for my soc of gender class! thanks for the time-saver, Kieran!

eudoxis 09.22.05 at 9:45 am

The thing that really strikes me about the NYT story by Louise Story is that it does not recognize just how difficult it looks to be a dual-earner family in your twenties with kids. Young, ambitious women know that the reality is that they have two choices: advance or see their kids, spouse, friends. This isn’t really a choice.

It’s an unpleasant choice even in your thirties or forties and even when a spouse has a high income and it makes more sense to stay home.

I think that the problem this choice presents is greater for women in ambitious careers because of increased time and emotional sacrifices such careers demand. It is at the same time more difficult to give up such a career and more difficult to raise a family.

I disagree with Kieran that there is no loss of social status for women with high earning spouses who choose to stay home with children. The reason for that is that many women in that stratum do have careers and form a powerful social incentive to be superwoman. Even comments of the last few posts indicate a disdain for women who supposedly choose to live a life of leisure. It’s rarely the case that smart and ambitious women at home do nothing but raise children. Just for example, they play an important role in community, the arts, and support networks that are no less hard work because they are largely uncompensated. (Plus, they run errands and blog on their own time.)

Kieran Healy 09.22.05 at 10:00 am

Tad, I continue to blame any unclarity on my sleepy state when I wrote this. Maybe just something like “Some Data on Families in the Workforce” would be better. I’ll change it.

theorajones 09.22.05 at 10:11 am

I agree with Eudoxis–we hear all the time that women who aren’t earning money have wasted their education.

This is somewhat bizarre, as earning money is no evidence you’re using your education, and certainly no evidence that you’re contributing to society.

Just another example of that old double standard in action–women’s work isn’t as valued as men’s, so women who raise kids are forced to point out all the OTHER things they also do in order to get respect.

Matt Austern 09.22.05 at 11:07 am

The flap about the Times article is not because people think the trend it reports on is a bad thing. The flap is because the article is an incredibly sloppy piece of work, and the article gives no reason to take seriously the claim that the trend is there in the first place. The article uses vague words like “many” that result in the article saying nothing while pretending to say a lot, and it asserts that there is a trend without showing any evidence that things are different today than they were in the past. It’s a textbook example of amateurish social science research, and of reporters’ inability to write about quantitative subjects.

Kieran’s graphs on labor force participation are interesting. They do seem to show a clear decades-long trend, and a smaller but also clear change some time around 2000. It would be interesting to learn more about what that change means.

Barbara Marwell 09.22.05 at 2:04 pm

As a 66-year old woman who had children, a career that was part-time when my children were young; full-time as they moved into middle and high school; and a husband who eared a good but not corporate lawyer or investment banker income, I am interested in some of the implications of this alleged trend. Although the NYTimes article may have been sloppy and based on 60 Harvard and Yale women, the recourse to BLS data may be masking something that really is happening.

I observe my daughter-in-law who fits the NYTimes description: 40 now, Yale graduate, high-powered career that was dropped partly because of the dot.com bust, partly because of difficulties in finding good reliable childcare; financially successful husband. Most of her friends (and she has a large circle, albeit not any kind of sample) are following the same course. The subjects of the article may not be a large group of women; but perhaps a significant one that deserves a careful, systematic survey to determine what is happening.

My concerns are not for these women now, but for their feelings of self-esteem and satisfaction with their lives when they are in their later forties and fifties, with children who do not require as much physical care. Will we be in another version of the feminine mystique? More importantly, when will we as a society provide appropriate supports and make the kinds of adaptations, especially in the workplace, that will permit highly-educated men AND women to have satisfying family, professional and personal lives.

MQ 09.22.05 at 2:16 pm

“It’s a textbook example of amateurish social science research, and of reporters’ inability to write about quantitative subjects.”

People don’t want to read quantitative social science research in the morning paper. They want to gossip about stuff. The NY Times article has got us all gossiping, hence it was a good article.

Elizabeth 09.23.05 at 10:26 am

On the question of what happened in previous recessions, you should take a look at this BLS paper entitled “Are Women Leaving the Labor Force?” The interesting thing about it is that it was published in 1994, during a recession, just before women’s labor force participation hit new all time highs.

My analysis of the trends (from about a year ago) is at http://www.halfchangedworld.com/2004/10/whos_opting_out.html.

James Chalmers 09.23.05 at 2:47 pm

“The next figure shows trends in the labor force participation rate of mothers with children under the age of 18. (You can get it as a PDF file.) Here the trend (obviously) is one of consistent growth.”

Austern is right. The trend is one of consistent growth until 2000 when for sure the numbers turn down and maybe something significant occurred. Brings to mind Stein’s First Law, “If something cannot go on forever, it will stop.” Though in this instance, it may have stopped shy of the male rate.

Notice too that the original NYT piece was mostly about women with more real choices than the rest of the labor force–highly educated and pretty well off.

Tom Hudson 09.25.05 at 8:29 pm

My wife, thinking of her parents, points out that in the last few years more Baby Boomers have reached retirable age. That’s moved both our sets of parents from two-earner to single-earner households.

Comments on this entry are closed.