Via Chris Uggen, some new Bureau of Justice Statistics for incarceration in the United States as of mid-2005. Imprisonment rose by 1.6 percent on the pervious year, and jail populations rose by 4.7 percent, for a total of just over 2.1 million people behind bars. The total population in prison has gone up by almost 600,000 since 1995.

Women make up 12.7 percent of jail inmates. Nearly 6 in 10 offenders in local jails are racial or ethnic minorities. In mid-2005, the BJS reports that “nearly 4.7 percent of black males were in prison or jail, compared to 1.9 percent of Hispanic males, and 0.7 percent of white males. Among males in their late 20s, nearly 12 percent of black males, compared to 3.9 percent of Hispanic males and 1.7 percent of white males, were incarcerated.” State by state, “Louisiana and Georgia led the nation in percentage of their state residents incarcerated (with more than 1 percent of their state residents in prison or jail at midyear 2005). Maine and Minnesota had the lowest rates of incarceration (with 0.3 percent or less of their state residents incarcerated).”

(You can get this figure as a PDF file if you like.)

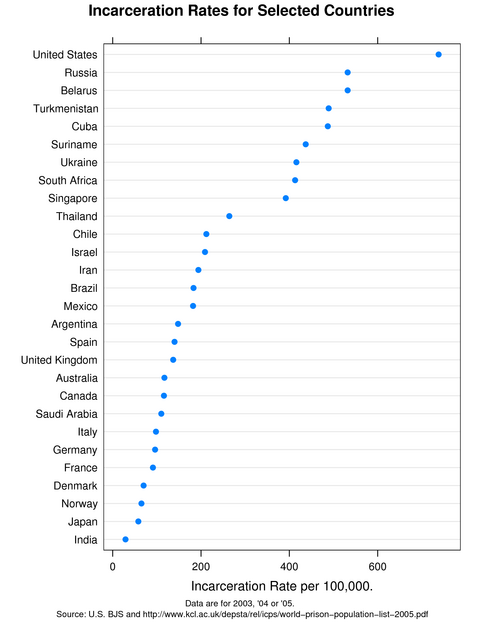

Comparative context is provided by Roy Walmsley’s World Prison Population List. The U.S. has an overall incarceration rate of 738 per 100,000 people, the highest in the world. Belarus, Russia and Bermuda (!) come next, distantly trailing with rates in the 530s. Fifty eight percent of countries have incarceration rates below 150 per 100,000. There is a lot of heterogeneity within continents. I left China out of the figure above — its incarceration rate is 118, but this only includes 1.55 million sentenced prisoners, not trial detainees or those in “administrative detention.”

{ 5 trackbacks }

{ 54 comments }

Sebastian Holsclaw 05.23.06 at 12:19 pm

Is there a reliable place to find out how many of those are in prison because of illegal drugs? I have a feeling (unsupported by any hard data that I have access to) that if the US scaled back the war on drugs a huge portion of the imprisoned population wouldn’t be there. (I also tend to believe that the war on drugs has other negative externalities so I’m worried about confirmation bias.)

Kieran Healy 05.23.06 at 12:32 pm

Look “here”:http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/bjs/dcf/enforce.htm for information on drug-law enforcement (i.e., arrests, etc); and “here”:http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/bjs/dcf/correct.htm for drug-related information about the prison population. In 2002 about a quarter of local jail inmates had a drug-related crime as their most serious offense. This is about the same number (a little higher) than in 1989. In state prisons, between 1995 and 2001, “As a percentage of the total growth, violent offenders accounted for 63% of the total growth, drug offenders 15%, property offenders 2%, and public-order offenders 20%.”

Steve LaBonne 05.23.06 at 12:36 pm

This site has assorted statistics, which appear to be culled from authoritative sources, which support that perception (though I must say that the figures showing only around 1/5 of state prisoners are incarcerated for drug offenses are lower than I would have guessed.)

dca 05.23.06 at 1:06 pm

One factor to keep in mind is that the US imposes (I think) much longer sentences than are the norm in Europe. So for the same rate of putting people behind bars you would get a much higher number there, since they stay longer. Anyone know more about this?

Max 05.23.06 at 1:33 pm

Bruce Western has done some interesting work on US incarceration rates here and here. There’s also a really good podcast here with Bruce Western and others discussing class, race and prison.

luci 05.23.06 at 1:40 pm

“the figures showing only around 1/5 of state prisoners are incarcerated for drug offenses are lower than I would have guessed”

Yeah, me too.

55% of federal prisoners in for drug offenses. 21% of state prisoners in for drugs.

I believe the federal prison population is about one tenth of the state system, so ~25% incarcerated for drug offenses, state and federal combined?

abb1 05.23.06 at 1:43 pm

Any correlation with the Gini index?

Sebastian Holsclaw 05.23.06 at 1:56 pm

“One factor to keep in mind is that the US imposes (I think) much longer sentences than are the norm in Europe.”

I think this is fairly important to note. I wouldn’t mind if the yearly rate of new incarcerations went down compared to other countries (especially vis-a-vis drug offenses). I’m completely untroubled on the other hand by any part of the statistic driven by keeping murderers or rapists in prison for the rest of their lives.

Sebastian Holsclaw 05.23.06 at 1:57 pm

“Any correlation with the Gini index?”

Eyeballing it, it would seem difficult considering the locations of such countries as India and Mexico.

almostinfamous 05.23.06 at 2:17 pm

well, as the saying goes in my neck of the woods, we don’t put our biggest criminals in jail, we put them in power.

roger 05.23.06 at 2:37 pm

It is interesting that Freedom indexes, often published by right leaning think tanks and magazines, rarely seem to consider incarceration rates in their mix — and certainly not as a value overshadowing, say, a friendly, deregulated atmosphere. It be nice if someone devised a realistic freedom index — one that took into account, for instance, lack of security (such as in Iraq) and the overincarceration of traditionally persecuted minorities (the U.S.)

well, it 05.23.06 at 2:41 pm

Christ, can you believe how many criminals are running around free in India and Japan, just, like roaming the streets?

Look, if false imprisonment is outlawed, only outlaws will be falsely imprisoned.

Except.

y81 05.23.06 at 2:49 pm

almostinfamous (#10): True, but that saying applies with equal force to every country on the chart.

DC 05.23.06 at 4:08 pm

I calculate, well, my calculator calculates, that if China had an incarceration rate equal to that of the U.S. there would be 9,697,126 people in Chinese prisons. (Taking the Chinese population according to the CIA World Factbook.)

As for a Gini correlation, a second “eyeballing” might hint at some such among OECD countries, at least to see Japan, Denmark and Norway down there.

KCinDC 05.23.06 at 4:45 pm

The effect of the war on drugs isn’t easy to determine because some nondrug crimes (thefts, murders, etc.) might not have happened if the war on drugs weren’t driving up the prices so much. (On the other hand, a drug war supporter could argue that more nondrug crimes might have been committed by people on drugs if the rate of drug use were higher, as it might be without the drug war.)

Patrick S. O'Donnell 05.23.06 at 4:48 pm

If anyone is interested in a reading list that might help one make sense of this data, among other things, I’ve compiled a bibliography on ‘criminal law, punishment & prisons’ (with Internet sites as well) that I will send along (as Word doc.) if you e-mail me at libertyequalitysolidarity.psod ‘at’ cox.net

Best wishes,

Patrick S. O’Donnell

rollo 05.23.06 at 5:35 pm

Sebastian #1-

” …if the US scaled back the war on drugs a huge portion of the imprisoned population wouldn’t be there…”

Yes. And we can take the stated goals of the “war on some drugs” at face value and think that just being sensible and rational about it might help.

Or we could wonder if maybe the purpose of the campaign was to produce the result our more naive brethren see as flawed and unintentional outcome.

So that the high rate of young black male incarceration is why, not because of.

The festering corners of revolution swept clean by the double temptations of illegal drugs and the profits they bring.

Tracy W 05.23.06 at 5:46 pm

11. – Including prison population in an index on welfare would need to be balanced somehow with crime rates, as a high crime rate reduces freedom too. This would require a controversial judgment as to the impact of imprisonment or the threat of imprisonment on crime.

I find that it’s funny how imprisonment rates so often get discussed without any discussion of crime rates. I’m interested in restorative justice and I’ve read a number of articles in favour of it that start something like “NZ has one of the highest imprisonment rates in the OECD …” and proceed from there with absolutely no discussion of crime rates or hint that the author considers that public policy might think about the victim as well as the criminal.

Brett Bellmore 05.23.06 at 6:00 pm

You also have to consider that a fair number of authoritarian/totalitarian countries are, for all practical purposes, large prison camps. What’s the point of having a tiny percentage of your population in nominal prisons, if the people outside those prisons aren’t free?

That 4.7% figure for black males is troubling, though; What can we do to get them to commit fewer crimes?

DC 05.23.06 at 6:05 pm

Tracy W,

Is not the point that having to incarcerate so many people indicates a massive failure of social integration? In other words, this is true regardless of whether one does or does not think it is an appropriate or necessary response to crime. It is also true regardless of where one chooses to look for explanations of the failure.

Patrick S. O'Donnell 05.23.06 at 6:13 pm

On another blog (Sentencing Law and Policy), I pasted the following material in response to one of the incarceration reports above in the hope that, here and there, it might illuminate some of the causes and effects surrounding this country’s unconscionably high and unjustly discriminatory incarcertion rates:

‘Criminal conduct is no lower class monopoly, but is distributed throughout the social spectrum. Indeed, whilst “street crimes†and burglary attract the most attention, the less visible crimes of the powerful may be argued to produce significantly greater social harm, in terms of both monetary loss and of physical injury and death. But the same is not true of the distribution of punishment, which falls, overwhelmingly and systematically, on the poor and the disadvantaged. Discriminatory decision-making throughout the whole criminal justice system ensures that the socially advantaged are routinely filtered out: they are given the benefit of the doubt, or are defined as good risks, or simply have access to the best legal advice. Serious, deep-end punishments such as imprisonment are predominantly reserved for the unemployed, the poor, the homeless, the mentally ill, the addicted, and those who lack social support and personal assets. Increasingly, this class bias has taken on a racial complexion, as disadvantaged minority groups come to be massively over-represented in the prison population and on death row.’–Antony Duff and David Garland

‘The dramatic increase in resources devoted to the punishment of crime in recent years’ should take cognizance of the fact ‘expanding punishment resources will have more effect on cases of marginal seriousness rather than those that provoke the greatest degree of citizen fear. The result is that when fear of lethal violence is translated into a general campaign against crime, the major share of extra resources will directed at nonviolent behavior.’ [….] [C]rime crackdowns have their most dramatic impact on less serious offenses that are close to the margin between incarceration and more lenient penal sanctions. The pattern of nonviolent offenses absorbing the overwhelming majority of resources in crime crackdowns can be clearly demonstrated in the recent history of criminal justice policy in the United States. During the decade 1980-1990, for example, the state of California experienced what might be described as the mother of all crime crackdowns. In ten years, the number of persons imprisoned in California quadrupled, and the population of those incarcerated in the state’s prisons and jails increased by over 100,000.’–Franklin E. Zimring and Gordon Hawkins

‘For those who wonder why both violence and the rate of imprisonment increased in the late 1980s, we present the parable of the bait-and-switch advertisement. [….] The “bait-and-switch†character of anticrime crusades occurs in the contrast between the kind of crime that is featured in the appeals to “get tough†and the type of offender who is usually on the receiving end of the more severe sanctions. The “bait†for anticrime crusades is citizen fear of violent crime. Willie Horton is the poster boy in the usual law and order campaign. But the number of convicted violent predators who are not already sent to prison is rather small. In the language of “bate-and-switch†merchandising, the advertised special is unavailable when the customer arrives at the store. The only available targets for escalation in imprisonment policy are the marginal offenders and offense categories. If an increase in severity is to be accomplished, the target of the policy must be “switched.†Nonviolent offenders go to prison and citizens wonder why rates of violence continue to increase.†–Franklin E. Zimring and Gordon Hawkins

‘If asked to describe the major changes in penal policy in the last thirty years, most insiders would undoubtedly mention “the decline of the rehabilitative idealâ€â€¦.’ But we might also discuss the ‘fading of correctionalist and welfarist rationales for criminal justice interventions; the reduced emphasis upon rehabilitation as the goal of penal institutions; and changes in sentencing law that uncouple participation in treatment programmes from the length of sentence served. “[R]ehabilitative†programmes do continue to operate in prisons and elsewhere, with treatment particularly targeted towards “high risk individuals†such as sex offenders, drug addicts, and violent offenders. And the 1990s have seen a resurgence of interest in “what works?†research that challenges some of the more pessimistic conclusions of the 1970s. But today, rehabilitation programmes no longer claim to express the overarching ideology of the system, not even to the leading purpose of any penal measure. Sentencing law is no longer shaped by correctional concerns such as indeterminacy and early release. And the rehabilitative possibilities of criminal justice matters are routinely subordinated to other penal goals, particularly retribution, incapacitation, and the management of risk. [….] For most of the twentieth century, penalties that appeared explicitly retributive or deliberately harsh were widely criticized as anachronisms that had no place within a “modern†penal system. In the last twenty years, however, we have seen the reappearance of “just deserts†retribution as a generalized policy goal in the US and the UK, initially prompted by the perceived unfairness of individualized sentencing. [….] In a small but symbolically significant number of instances we have seen the re-emergence of decidedly “punitive†measures such as the death penalty, chain gangs, and corporal punishment. [….] Forms of public shaming and humiliation that for decades have been regarded as obsolete and excessively demeaning are valued by their political proponents today precisely because of their unambiguously punitive character. [….] The feelings of the victim, or the victim’s family, or a fearful, outraged public are now routinely invoked in support of new laws and penal policies. There has been a noticeable change in the tone of official discourse. Punishment—in the sense of expressive punishment, conveying public sentiment—is once again a respectable, openly embraced, penal purpose and has come to affect not just high-end sentences for the most heinous offences but even juvenile justice and community penalties. The language of condemnation and punishment has re-entered official discourse and what purports to the “expression of public sentiment†has frequently taken priority over the professional judgment of penological experts.’ –David Garland

‘A highly charged political discourse now surrounds all crime control issues, so that every decision is taken in the glare of publicity and public contention and every mistake becomes a scandal. The policy-making process has become profoundly politicized and populist. Policy measures are constructed in ways that appear to value political advantage and public opinion over the views of experts and the evidence of research. The professional groups who once dominated the policy-making process are increasingly disenfranchised as policy comes to be formulated by political action committees and political advisers. New initiatives are announced in political settings…and are encapsulated in sound-bit statements: “Prison works,†“Three-strikes and you’re out,†“Truth in sentencing,†“No frills prisons,†“Adult time for adult crime,†“Zero-tolerance,†“Tough on crime, tough on the causes of crime.†There is now a distinctly populist current in penal politics that denigrates expert and professional elites and claims the authority of “the people,†of common sense, of “getting back to basics.†The dominant voice of crime policy is no longer the expert or even the practitioner but that of the long-suffering, ill-served people—especially of “the victim†and the fearful, anxious members of the public.’ –David Garland

‘One of the most significant developments of the last two decades has been the emergence of a new style of criminological thinking that has succeeded in attracting the interest of government officials. With the fading of correctionalist rationales for criminal justice, and in the face of the crime-control predicament, officials have increasingly discovered an elective affinity between their own practical concerns and this new genre of criminological discourse. This new genre—which might be termed the new criminologies of everyday life—has barely impinged upon public attention, but it has functioned as a crucial support for much recent policy. [….] The new criminologies of everyday life are a set of cognate theoretical frameworks that include routine activity theory, crime as opportunity, lifestyle analysis, situational crime prevention, and some versions of rational choice theory. The striking thing about these various criminologies is that they each begin from the premise that crime is a normal, commonplace, aspect of modern society. Crime is regarded as a generalized form of behaviour, routinely produced by the normal patterns of social and economic life in contemporary society. To commit an offence thus requires no special motivation or disposition, no abnormality or pathology. In contrast to earlier criminologies, which begin from the premise that crime was a deviation from normal civilized conduct and was explicable in terms of individual pathology or faulty socialization, the new criminologies see crime as continuous with normal social interaction and explicable by reference to standard motivational patterns. Crime comes to be viewed as a routine risk to be calculated or an accident to be avoided, rather than a moral aberration that needs to be specially explained.’ –David Garland

‘The prison is used today as a kind of reservation, a quarantine zone in which purportedly dangerous individuals are segregated in the name of public safety. In the USA, the system that is taking form resembles nothing so much as the Soviet gulag—a string of work camps and prisons strung across a vast country, housing two million people most of whom are drawn from classes and racial groups that have become politically and economically problematic. The prison-community border is heavily patrolled and carefully monitored to prevent risks leaking out from one to the other. Those offenders who are released “into the community†are subject to much tighter control than previously, and frequently find themselves returned to custody for failure to comply with the conditions that continue to restrict their freedom. For many of these parolees and ex-convicts, the “community†into which they are released is actually a closely monitored terrain, a supervised space, lacking much of the liberty one associates with “normal life.†This transformation of the prison-community relationship is closely related to the transformation of work. The disappearance of entry-level jobs for young “underclass†males, together with the depleted social capital of impoverished families and crime-prone neighbourhoods, has meant that the prison and parole now lack the social supports upon which their rehabilitative efforts had previously relied. Work, social welfare, and family support used to be the means whereby ex-prisoners were reintegrated into mainstream society. With the decline of these resources, imprisonment has become a longer-term assignment from which individuals have little prospect of returning to an unsupervised freedom.’ –David Garland

Adam 05.23.06 at 6:17 pm

Regarding disproportionate imprisonment of minorities, there’s an interesting article at La Griffe du Lion that argues that that is a result of (or is exacerbated by) more lenient enforcement and sentencing in more liberal states. Thought-provoking stuff.

roger 05.23.06 at 6:36 pm

Tracy, I agree with you about the crime factor, which is why I included the Iraq example — lack of security. That is one of the reasons Iraq’s inclusion as the third or fourth freest state in the Middle East by the Economist was so laughable. And of course the crime question is also about systematic white collar crime, too. The collapse of the soviet union was succeeded by the seizure of major resources by the mafia, who proceeded to become ‘entrepreneurs.’ Is this really an increase in freedom? It is funny that the president of Yukos would be so extensively defended by newspapers in the States, after he was arrested by Putin, when — if he lived in the states — he would have been arrested in the 90s and charged, at the very least, under RICO. Similarly, when you read about the conspiracy among users of asbestos to keep the facts about asbestos from their workers for years, and the fact that this involves no jail time, whereas selling a bag of pot or a foil of cocaine can involve five to ten years, shows you a seriously screwed up system.

Kenny Easwaran 05.23.06 at 7:50 pm

Another interesting point of comparison for countries like China and Singapore is the fact that by executing criminals, or applying corporal punishment rather than imprisonment, they keep their prison populations artificially low. (I’m not including the US in there, because I imagine with just a few hundred people executed in the last 30 years, it hasn’t made a serious dent in the prison population.)

radek 05.23.06 at 8:14 pm

As far as the over representation of minorities in the prison population – it’s been a while since I read up on it but I remember that a good portion of it is due to discrimination at the district attorney level. In other words for the same act, minorities get charged with a more serious offense. A white guy gets a citation for jaywalking, a black guy criminal mischief 1st degree. A white guy gets a manslaughter charge, a black guy murder 1. The white college hippy gets misdemeanor possession, the black kid possesion with intent to distribute. etc. As I recall this explained a very large portion of the difference.

Tracy W 05.23.06 at 11:15 pm

I agree that high crime rates and high imprisonment rates may be the sign of a failure of social integration.

But the connection between crime and imprisonment is complicated. A rising rate of imprisonment may be part of a return to social integration (think of imprisoning wife beaters). According to the US Department of Statistics the crime rate has been falling while the imprisonment rate has been increasing. This may be due to changing age structures or legalised abortion, or it may be due to locking up lots of people so they can’t commit crimes (I did say that the relationship between crime and imprisonment is controversial – any group trying to include imprisonment rates in an index should have a long argument about what sign the measure should have).

And focussing just on imprisonment rates risks misdefining the problem as too many people in prison, not too many crimes being committed.

One depressing fact, which people talking about differing incarcentation rates of ethnic minorities often forget to mention or perhaps don’t even think of, is that disadvantaged ethnic minorities are often disproportionately victims of crime (according to victim surveys). Eg according to this study, black men aged 16-24 compromise only about 1% of the overall population, but experience 5% of all violent victimisations. Here is some more evidence (pdf) on victims of violent crime, which shows that inhabitants of households earning less than $7,500 have a 46 per 1,000 annual rate of being victims of a violent crime, while inhabitants of households earning more than $75,000 have an 18.8 per 1,000 rate. These sort of differences in victimisation rates between the poor and the rich should be compared to differences in imprisonment rates between the poor and the rich before deciding that the imprisonment rate of the poor is too high.

As for Yukos being defended in the States – I strongly suspect that was driven by fear for democracy. Russia does not exactly have a history of independent government where one can vigorously disagree with the head of state and still go about your business peacefully (I’m thinking of the Czars nearly as much as of the Communists). And by the accounts of my relatives who have worked in Russia, Yukos was hardly the only business leader who was involved in criminal activities – the case has strong hints of a man being prosecuted because he was a threat to Putin’s control of the state, not because he was a criminal. Read one of the Rumpole books by John Mortimer if you want more of a philosophical defence of the importance of proper procedures even when the accused is likely guilty.

I can offer no explanation as to why the US government gets so carried away about drug buying and selling.

Tracy W 05.23.06 at 11:46 pm

Incidentally Patrick, the figures in these documents on crime rates – showing a dramatic rise in the 1960s and 70s may explain why experts and professional advice have fallen in value in debates over crime in the last couple of decades.

This rise is probably not the fault of professionals, and the fall probably has very little to do with governments’ actions to reduce crimes, but voters don’t tend to dig deeply into causes. Many people regularly confuse correlation and causation.

Russ 05.24.06 at 12:29 am

…large as the slice of the currently incarcerated citizen pie this might be, how many are “ex” cons or formerly incarcerated…? I mean, most get out eventually and still we keep backfilling. What percentage of our citizenry have “done time”…? Anyone got numbers…?

Tim Worstall 05.24.06 at 5:55 am

“I agree that high crime rates and high imprisonment rates may be the sign of a failure of social integration.”

Could be. In the US the idiot War on Drugs, Russia, Belarus, Turkmenistan, until recently Ukraine (and I don’t know anything about Suriname) all authoritarian to a great extenet.

What’s Cuba’s excuse?

abb1 05.24.06 at 6:25 am

That it includes Guantanamo Bay.

JohnLopresti 05.24.06 at 11:42 am

I am glad to see the sociologic spotlight upon the incarceration topic.

It is true incarceration is used for social engineering in some civilizations where lawmaking constructs are weakest.

Beyond that, being somewhat an original thinker, I felt sad that Bernie Ebbers was sentenced to essentially the rest of his elderly life for having stolen millions from his telecom company and shareholders. Disproportionate adjudication, I would say. Then we have sentencing guidelines; additionally, there is the unwritten counterbalancing effect of what is called ‘atmosphere’, i.e., during some political times sentencing is less applied or less severely applied. In CA we have had a lot of media designed sentencing concepts, whereby now, after more than a decade in service, a law compelling 25 years to life for a shoplifter if it is his or her third felony, is an initiative that is being revised as people recognize it is too harsh.

Some links:

http://www.ussc.gov/bf.htm

Booker and Fanfan Materials

US government sentencing guidelines site

http://sentencing.typepad.com/sentencing_law_and_policy/

OSU sentencing and law policy professors website.

http://lawprofessors.typepad.com/whitecollarcrime_blog/2006/05/does_the_speech.html

What it means to create a white collar precedent by searching a sitting congress person’s capitol hill office.

Matt 05.24.06 at 12:10 pm

Christian Parenti’s _Lockdown America_ is still the best work of sociology on this stuff. Though God knows, his statistics are most likely conservative, by now.

His main thesis is that the US incarceration/militarization boom was originally a preemptive (and increasingly economic) response to the social (and racial) upheaval of the 60s, in various respects.

Of course Hardt and Negri discuss the larger context of permanent war and US ‘exceptionalism’, with accessible summary of Schmitts and Agambens. And Derrida wrote emphatically to Clinton on Mumia Abu-Jamal’s behalf…blasted Theorists!

Sebastian Holsclaw 05.24.06 at 12:59 pm

“In CA we have had a lot of media designed sentencing concepts, whereby now, after more than a decade in service, a law compelling 25 years to life for a shoplifter if it is his or her third felony, is an initiative that is being revised as people recognize it is too harsh.”

I think in general people are not ‘recoginizing’ any such thing. The last four attempts to significantly soften the three strikes initiative have been met with extreme resistance by the voters in California.

Doctor Memory 05.24.06 at 2:32 pm

From the original Kings College document from which the graph is taken: “In almost all cases the original source is the national prison administration of the country concerned.” It then goes on to acknowledge a few humble deficiencies in this method, such as “different practice in different countries” regarding minors and the mentally ill and (a very delicate phrasing here) the possibility that not all detainees are “under the authority of the prison administration.”

Not to belabor the bleedingly obvious here, but on a list which contains such countries as China, Belarus, Egypt, Iran, and Russia, isn’t the pertinent problem that there is no reason whatsoever to trust the published numbers? And in fact, there is every reason to believe that the official figures are entirely created by the local propaganda offices? Or did we suddenly wake up on the alternative earth where the USSR happily handed Amnesty International detailed reports on the composition of the gulags?

Justin 05.24.06 at 4:30 pm

Woo hoo!!!! We’re #1!!! USA!!! USA!!!

DC 05.24.06 at 7:22 pm

Doc,

Maybe, but why did “the local propaganda offices” in Russia and Belarus place themselves so damn high on the list? OK, not as high as the US, but streets ahead of anything in, say, the EU?

Doctor Memory 05.25.06 at 9:32 am

dc: I don’t think it’s too much of a stretch to imagine that someone, somewhere, has the latitude to require that the numbers pass some version of the laugh test. “Somewhere between Denmark and the US” isn’t exactly a narrow target range to hit.

Barry 05.25.06 at 10:08 am

JohnLopresti: “Beyond that, being somewhat an original thinker, I felt sad that Bernie Ebbers was sentenced to essentially the rest of his elderly life for having stolen millions from his telecom company and shareholders. Disproportionate adjudication, I would say. ”

I’d say – on the low side. Ebbers, Lay at al. should really face the death penalty.

jet 05.25.06 at 11:14 am

Yeah, and where would the US fall in a graph showing percentage of the population victimized by crime? That stupid graph barely tells part of the story and means absolutely nothing by itself.

Mexico has a much lower incarceration rate than the US, but there is significant pressure to introduce capital punishment for kidnapping, since so many people are kidnapped. Don’t even mention how large portions of the country are under de facto administration by organized crime.

South Africa has a much lower incarceration rate than the US, but children are more likely to be raped than to go to school.

Saudi Arabia has a much lower incarceration rate than the US, but tribal customs still allow for ritual murder and the virtual enslavement or a large portion of the population.

Etc.

engels 05.25.06 at 12:08 pm

And for CT’s soi disant “libertarian” the answer is of course: “Big deal!”. Not a surprise, but still nice to have it in writing. Thanks for that, Jet!

Mexico has a much lower incarceration rate than the US, but…

Mexico…

South Africa…

Saudi Arabia…

Etc.

Well, go on, Jet. You’ve got a lot of countries to get through.

DC 05.25.06 at 12:22 pm

“Somewhere between Denmark and the US†isn’t exactly a narrow target range to hit.

No, but still, they’ve placed themselves remarkably nearer the latter than the former if the figures are purely propoganda. They seem to boast of something like 540 per 100,000 in prison, not exactly an image of a liberal haven.

Anyway, granting figures may be unreliable in some cases, what’s your feeling – do you reckon many of these countries really have prison populations comparable to that of the US?

jet 05.25.06 at 12:41 pm

Engels, my blinkered friend, I never said “big deal”. I said it was only a small piece of the puzzle.

Incarceration is a symptom of a problem which can manifest itself differently if a society doesn’t put its criminals in prison. And I was showing the different manifestations of that problem in countries with lower rates of incarceration, to make my point that blowing on and on about how this graph shows the US has a much worse problem with crime and punishment than other countries is just silly and illogical.

engels 05.25.06 at 1:00 pm

The point isn’t that “the US has a much worse problem with crime and punishment than other countries”. The point is that the US has a much worse problem with FREEDOM.

jet 05.25.06 at 1:53 pm

Engles,

Are you saying that South Africa has a better result because, while children are raped more often than they learn to read, the rapers have more FREEDOM?

engels 05.25.06 at 2:09 pm

Jet – If you lock someone up, you take away her freedom. If you lock lots of people up, you take away lots of people’s freedom. Whatever else is going on in the country, anyone who cares about freedom ought to think that the number of people being locked up is a matter of great importance in itself. But you don’t.

abb1 05.25.06 at 3:15 pm

Interesting thing about Scandinavians: they have low incarceration rates and low crime rates, but also being incarcerated in their prisons (so I’ve heard) is pretty much like staying at Motel 6 with room service and cable TV (not to mention medical care and education). Not exactly a strong deterrence. How do they do it?

jet 05.25.06 at 3:19 pm

Engels,

Like any good Libertarian, I believe that a person forfeits protections of their rights as they infringe upon the rights of others. And you have found yourself in the peculiar position of defending the freedom of child rapists in South Africa.

If you want to discuss causes of crime, that might be more enlightening. Asking why the US has such high levels of crime is a thought worth pursuing. Of course in the context of Kieren’s dandy little chart that would lead to questions of why does South Africa have such high levels of crime to make the US look like Denmark, yet let those criminals walk the streets preying upon innocents. I have a terrible, yet nagging feeling that in Engles’ world, criminals shouldn’t be punished, only the victim and society should be blamed for forcing the criminal into his crimes.

But saying the US is worse than South Africa because the US denies child rapists their freedom is a non starter for everyone except possibly you.

engels 05.25.06 at 3:44 pm

So it’s the old “how a society treats its (petty) criminals is of no moral importance”. But this is obviously not true. And also, because any system of justice is imperfect, having a higher prison population will mean that you have a higher number of innocent people in prison. But can I really take this to be an accurate summary of your position:

Yes, American citizens are, on average, more likely to be unfree then Danish citizens, but it is their own fault? It doesn’t sound very patriotic.

And, no, I didn’t make a stupid overall comparison between the US and South Africa. And I am not calling for criminals to be freed. I am pointing out that their loss of freedom is still a loss of freedom.

DC 05.25.06 at 3:53 pm

Number 48 is superb.

But seriously, Jet, are South African children really “more likely to be raped than to go to school”?

jet 05.25.06 at 9:27 pm

dc,

This thread is a joke so of course I’m going to have some fun.

But on a more serious note Hell is a real place for a lot of South Africans. Stop and think about that shit for a while and see if it doesn’t mess with you.

engels 05.25.06 at 11:49 pm

Jet – Thanks for raising everyone’s awareness of the situation in South Africa.

But to return to the actual topic of the thread it’s irrelevant (and in bad taste) for you to start screaming about child rapists. The US, in case you hadn’t noticed, does worse than every other country on the list. Perhaps you didn’t know: other developed countries jail rapists. Or, at least, they do as good a job of doing it as the US.

So I’ll ask you again: do you not think that, for someone who professes to care about liberty, and to dislike government coercion, the number of people whom the state deprives of their liberty, for whatever reason, might be a matter of concern in itself? And if you don’t think so, are you sure that it is really liberty that you care about?

jet 05.26.06 at 1:43 pm

Engels,

Is that really what this thread was about? Becuase I’m pretty damned sure that South Africa doesn’t do as good a job as the US in ensuring its citizens liberty, yet Kieren’s totally rad graph shows them with a much better outcome.

Or maybe I’m not seeing this way the Engles way and next you’ll point to Somalia with no penal system and tell me how they are the best in the world at securing liberty?

unbveleivable 05.28.06 at 10:33 pm

Let’s get a little perspective:

The United States has 5% of the world’s population and 25% of the prison population, or more than 2 million of eight million imprisoned worldwide.

About 1,222,000 of 1,983,000 incarcerated in 2000 are nonviolent, or 61.6%, not exactly a winning argument for the idea we are protecting society from the “worst” offenders.

(see:http://www.cjcj.org/pubs/punishing/punishing.html)

Remember also, many crimes defined as violent, may be bar fights, domestic disputes and DUI collisions–bad events perhaps, but not necessarily the work of career criminals.

An entrenched corrections industry, replete with glitzy Las Vegas conventions and lobbyists are a driving force in criminal justice expenditures and policy, if you can call lining your pockets a policy. And the conviction-driven prosecutors armed with mandatory sentencing who have taken judicial discretion away from the courts.

(see: Paul Craig Roberts, Presumed guilty, http://www.counterpunch.org/roberts12212005.html)

Releasing millions of americans back into their communities (96% of all prisoners are released), saddled with lifelong “felonies” that bar them from meaningful employment, six million children living as orphans of the prison boom, should not nake any of us feel safer.

Tonight on one of those interminable “cop” shows, I watched Las Vegas police incarcerate a women for stealing two packages of steak. She had a six month old child in the car, and they made clear the child would be placed in state custody, and probably into the foster care system, since she had no relatives to care for it. They had no choice either.

That should really work out well. Nice use of public resources.

unbveleivable 05.28.06 at 10:39 pm

Oh yeah, one more thing. The capital punishment “Red’ states are leaders in violent crime after decades of ‘tough’ crime policies. try New Hampshire or Norway if you want a relatively peaceful civic encironment.

But then we wouldn’t enjoy the bloodlust, crappy legal representation, phony phorensic labs with liars giving expert testimony and false convictions.

Comments on this entry are closed.