As Henry mentioned this morning, I’ll be doing a series of guest posts at Crooked Timber this week. I’m grateful for the invitation. My posts will be on strategies for reducing income inequality in the United States.

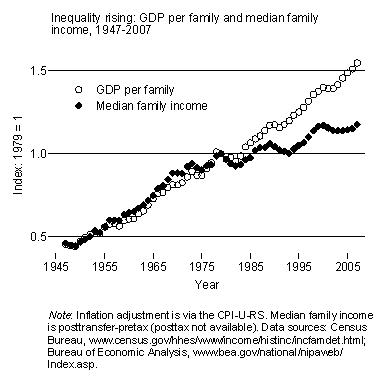

Here’s the problem (more discussion here):

There are two linked components to this rise in inequality: the surge in incomes for those at the top of the distribution and the slow growth of incomes for those in the middle and at the bottom.

Is this really a problem? Would it be better if income inequality were reduced? I think so, for the following reasons.

1. Fairness. Market processes have produced enormous incomes for various financial operators, CEOs, entrepreneurs, athletes, and entertainers in recent decades. A good bit of this is due to luck — being in the right place at the right time, genetic talent, having the right parents or teacher or coach, and so on. I don’t mind some inequality due to luck, and I recognize that monetary incentives are helpful. But the current (or recent, I should say;Â the downturn will reduce top incomes somewhat) magnitude of inequality in America strikes me as unfair. An income of several hundred million dollars when the minimum wage gets you about $15,000 is too much inequality. What’s the proper amount of income inequality? I don’t have a precise answer, but that doesn’t mean it’s wrong to feel that our current level is excessive.

2. Inequality’s consequences. Even if you don’t worry about exorbitant incomes in and of themselves, there’s no avoiding the fact that they have consequences for the incomes and well-being of Americans in middle and lower parts of the distribution. The social pie isn’t zero-sum. But our economy hasn’t grown faster in the past few decades than it did before, so the dramatic jump in incomes among those at the top has come in part at the expense of the rest of us. The following chart offers one way to see this. It shows GDP per family and median family income over the past six decades. Relative to growth of the economy, incomes in the middle (and below) have increased slowly since the 1970s.

As Robert Frank has pointed out, super-high incomes also have led to an arms race in consumption, especially in housing. Spending among the rich has escalated dramatically, encouraging middle- and upper-middle-class households to take on more and more debt in order to keep pace.

Over the past decade a number of social scientists have looked at the effect of inequality on other societal outcomes. We have studies suggesting that inequality is bad for education, health, crime, economic growth, economic mobility, civic engagement, political participation, political influence, and political polarization. I’m not convinced that all of these findings are correct, but some of them are quite plausible.

So what should we do? Stay tuned.

{ 76 comments }

Don C. 04.13.09 at 2:44 pm

“Fairness”?

Th top 1% of income earners pay 39% of all income taxes.

The top 25% pay 86%.

The top 50% pay 97%.

What could be “fairer”?

**

What should we do?

Cut the tax rates on the top earners/producers and, as history proves, revenue increases to the treasury to pay for social programs (charity).

Barbar 04.13.09 at 2:57 pm

Don C asks: What should we do?

We should have a modicum of intellectual honesty and (a) compare shares of federal income taxation to shares of income, and (b) remember that there are many other taxes besides federal income taxes (payroll taxes, state and local taxes, sales taxes).

Returning to the original post, what is Frank’s argument relating super-high incomes to rising debt levels? I really don’t see a necessary connection between the top 1% of incomes and the behavior of the rest of society.

StevenAttewell 04.13.09 at 3:07 pm

DonC: “Cut the tax rates on the top earners/producers and, as history proves, revenue increases to the treasury to pay for social programs (charity).” History does not prove this, it proves the opposite. The Reagan tax cuts and the Bush tax cuts resulted in massive deficits, and both coincided with cuts to social spending (with the exception of the Bush prescription drug benefit, which still came amidst cuts to all other social spending).

Lane:

Regarding fairness, I’d also point out that inequality is not being spread across even the elite evenly – the wealth for the last thirty years has increasingly been flowing to those engaged in the least useful endeavors, such as the FIRE (Finance, Insurance, and Real Estate) sectors, rather than even to those elites who are involved in actually creating things of value to society. So there’s a deformation even at the top.

In regards to the impact of inequality, two obvious things spring to mind that aren’t in your list. The first is political – classical small-r republican theory teaches us that massive inequalities of wealth are bad, for reasons that go beyond “political participation, political influence, and political polarization.” Classical republicans believed – and I would argue, rightly – that economic power and political power bleed into each other, and that the existence of great concentrations of wealth damages the presumption of equality that a republic is based on. Even leaving aside the issue of direct influence, I think it’s done damage to our political imagination – he rich have been given huge amounts of deference in policymaking because we’ve valorized the corporation as the most efficient institution and the businessman as the source of innovation, we try to turn governments into businesses because businesses are deemed the best form of organization, and we seek for government-through-CEOs with the election of people like Mitt Romney, Mike Bloomberg, Arnld Swartzenegger, etc. who run on a platform of making government run like a business.

The second is economic, and just re-emphasizes the point that the marginal propensity to consume is important here. Rich people don’t spend enough to create a solid foundation of stable consumers – hence, we’ve had to turn to other sources, notably a massive binge on credit to try to make up the difference. Well, look at the result now.

Don C. 04.13.09 at 3:10 pm

So, apply a modicum of “intellectual honesty” and present numbers you think fair (e.g., what should the average “minimum/living wage” be in America?).

What is the percentage of a person’s income that you feel is “fair” to confiscate in the form of taxes?

Don C. 04.13.09 at 3:12 pm

“The Reagan tax cuts and the Bush tax cuts resulted in massive deficits, and both coincided with cuts to social spending.”

That is false.

What hard evidence do you have that shows social spending decreased under either Reagan or Bush the elder?

Barbar 04.13.09 at 3:15 pm

Rich people don’t spend enough to create a solid foundation of stable consumers – hence, we’ve had to turn to other sources, notably a massive binge on credit to try to make up the difference. Well, look at the result now.

Is this really the direction of the causal arrow? Did the binge on credit occur because we had nowhere else to turn, or did it happen because there was a large supply of credit that had to go somewhere?

anonymous 04.13.09 at 3:26 pm

How Much Americans Actually Pay in Taxes

Second graph: share of pre-tax income vs. share of federal tax liabilities for five quintiles of income.

Note that this is for federal taxes, which are progressive; most state tax systems are actually regressive (because of high dependance on sales and property taxes) and so will even out this result a bit, making the share of liabilities a bit closer to the share of income. See this report for details.

So most people pay a little less a percent of their income than the average, while the very rich pay a little more. I don’t know whether you call that “fair”, but it certainly seems reasonable. At any rate, I don’t remember when market economics was ever concerned with “fairness”–what really matters is what tax rate is acceptable enough to rich people that they won’t leave the country and thereby reduce overall revenues.

Righteous Bubba 04.13.09 at 3:28 pm

StevenAttewell 04.13.09 at 4:03 pm

Don C: Dang, Bubba got there first. I’d also recommend Perspectives on the Reagan Years by John Logan Palmer, The States, the People, and the Reagan Years by AFSCME (a good state-level account), etc. The fact that Reagan tried to cut social spending is not a wild conspiracy theory – he ran on a platform of cutting social spending, was ideologically opposed to social spending, and cut social spending.

Barbar: It’s a good question. I think that actually you can have both at the same time, i.e, that we needed debt to cover our consumption, and that we had capital that needed to be spent somewhere (indeed, if you take the position that the issue is an imbalance in wages/profits, the two are inherently linked). The question beccmes – what would have fueled economic growth if it hadn’t been massive debt? If incomes are stagnant and falling over time, you need something to make up the slack and cover the increasing inventories.

Don C: I am glad you asked “what should the average “minimum/living wage†be in America?) What is the percentage of a person’s income that you feel is “fair†to confiscate in the form of taxes?” These are important questions to answer, and progressives should enjoy answering them.

I would say that the minimum wage should be a living wage – i.e, enough to provide the basic necessities of life (housing, food, clothing, transit, etc..), the basics of economic security (health coverage, some form of retirement savings, child care, and so forth), and the potential for economic mobility (one’s own training/education, homeowning, enough savings to cushion against a sudden crisis, enough money for one’s children’s higher education). This site: http://www.livingwage.geog.psu.edu/ is quite helpful on this score. Take my state of California – it takes about $10.72/hr to make it as a single adult, and $24.62 to make it as a two adult/one kid household. I think that’s more than fair.

As for taxes, first of all, I don’t think of it as confiscation, but rather a purchasing of collective goods – roads, police, fire, schools, emergency health, and the like all cost money. I would say that it sort of depends on your income – being taxed at 50% of your income means destitution if you’re making $50,000 a year, but if you’re making $5,000,000 a year, I don’t see it as a burden because you’ve still got enough to live comfortably on. But thinking broadly, I would say that 0-5% is good for people earning within 150% of poverty, call it 10-15% for people within 250%, 15-25% for people within 350%, and upwards. Personally, I don’t have a problem with the old 90% top marginal bracket, because at that level of income, the cash is really only a way to keep score.

StevenAttewell 04.13.09 at 4:05 pm

* note – “and upwards” means increasing by about 5-10% as you go up in brackets.

lemuel pitkin 04.13.09 at 4:05 pm

It’s certainly true that inequality has increased over the past 25 years, but the first graph does nothing to illustrate this fact: the scale means that even if incomes at the middle of the distribution had grown as fast as those at the top, the bottom line would still look flat compared to the top one.

You should either use a log scale, or let 1985 income = 100 for all groups, or plot growth rates of incomes rather than levels.

Barry 04.13.09 at 4:08 pm

Lane, I strongly suggest contacting one of the CT regulars, and banning Don C. If you wonder why, go to the post ‘Really Really Bad Arguments’ (https://crookedtimber.org/2009/04/09/really-really-bad-arguments/) and see how many, tedious and noncontributory posts that guy made.

An intelligent, honest and energetic right-winger would be welcome; a tedious troll who can’t come up with an honest argument to save his life is not.

Matt Kuzma 04.13.09 at 4:53 pm

It’s always been my (casual, ignorant) observation that the underlying trend behind all the great social upheavals of history has been income inequality. Whenever there’s a great social injustice, the size of the reaction, from complete disinterest to violent revolution, I suspect tracks closely with income inequality. I know this is a terrible oversimplification, but I wouldn’t be surprised if social inequality tends to make societies less stable and more prone to revolt.

Barry 04.13.09 at 5:12 pm

Matt, I wouldn’t be surprised if *rapid change* in income inequality is better correlated; societies can last for long periods of time with massive inequality.

Blissex 04.13.09 at 5:30 pm

«I would say that it sort of depends on your income – being taxed at 50% of your income means destitution if you’re making $50,000 a year, but if you’re making $5,000,000 a year, I don’t see it as a burden because you’ve still got enough to live comfortably on.»

So you if someone stole $1,000 from someone making $1,000,000/y that would be less of a crime than if the $1,000 were stolen from someone making $10,000 a year? Aren’t citizen equal before the law?

And wouldn’t stealing $1,000 from someone highly productive who contributes $1,000,000 to the economy every year be more damaging than stealing the same sum from someone who hardly contributes to the economy?

People like DonC start from very different assumption than yourself; typically that high income is a reward for winning, low income is a punishment for losing, and that taxation is a way to rewards losers and punish winners, and to impoverish the nation, by stealing resources from those who contribute most to those who contribute least, and that since everybody deserve what they get, stealing from high income producers is as immoral or more immoral as stealing from low income parasites.

Indeed following that logic the moral solution would be to have taxes paid by lower income parasites to higher income producers, to ensure that resources be distributed in a progressive way, to those who create progress, not to those who hold it back.

There are very good objections to DonC’s assumptions: that paying USA taxes is entirely voluntary, and nobody is forced to give a cent to the USA government (I don’t for example), and that what he calls “welfare” is really an entirely voluntary insurance pool against misfortune, and that self-insurance is extremely inefficient even for the wealthy (think fat-tail distributions).

sleepy 04.13.09 at 5:46 pm

The Spirit Level: Why More Equal Societies Almost Always Do Better

http://www.guardian.co.uk/society/2009/mar/12/equality-british-society

StevenAttewell 04.13.09 at 6:00 pm

Matt/Barry: I’d side with Barry on this. Many political revolutions -the French and American Revolutions are the best case – don’t take place in either states or periods in which inequality is unusually high, or poverty unusually widespread. Rather, they tend to come right after a period of prosperity dramatically reverses, dashing expectations that had previously been quite high and raising fears of a sudden decline in station.

ben a 04.13.09 at 6:31 pm

It’s great to have Lane Kenworthy writing here. Two points, or maybe questions.

1) It would be interesting to understand the composition of the households set over time. For example, are the ‘bottom 20%’ in 1985 the same people as in 1995 and 2005, or have more ‘bottom households’ entered the sample — either through immigration or household. I suppose this is one aspect of the old “mobility’ argument, but rather than rehash that here, it would be more interesting to understand we actually know about the data. What kind of time course data do we have looking at “same household” analysis?

2) Lane writes: But our economy hasn’t grown faster in the past few decades than it did before, so the dramatic jump in incomes among those at the top has come in part at the expense of the rest of us. I am not exactly sure how the causal link here is supposed to work. Do we see any relationships like this *within* firms — i.e., that firms with lower than average growth of executive pay correlate with higher than average growth of line worker pay (or vice versa)?

Felix 04.13.09 at 7:08 pm

lemuel said: “You should either use a log scale, or let 1985 income = 100 for all groups, or plot growth rates of incomes rather than levels.”

It’s never been clear to me why people think comparing percentage increases in income is appropriate. If someone making $20,000/year gets a 1% raise, that gives them another $200/year, which is about 1 new television of improvement to their life. If someone making $20,000,000/year gets a 1% raise, that gives them another $200,000/year, which is much more than 1 new television of improvement to their life.

For general quality-of-life issues, comparing +$200 vs +$200,000 seems more meaningful than comparing +1% vs +1%.

David Wright 04.13.09 at 7:26 pm

You imply that the divergence of the two lines in your graphic of GDP/family and median family income is due to the super-wealthy taking a larger share of GDP. That’s a bit misleading. The share of GDP going to the non-median wealty is one factor, but a far larger contributor to that divergence is the tremendous increase in non-wage compensation — basically health insurance premiums.

It’s also worthwhile to keep in mind who the “non-median wealthy” are. The super-rich get all the press, but there aren’t enough of them to account for most of the change in the Gini coefficient. The increase is mostly accounted for by the ~$10K/year increase in the gap between the income of college graduates and non-graduates. To put a point on it: the really important drivers of inequality are not the CEOs, but people like the readers and writers of crookedtimber.

Certainly the rise in inequality is real and there are some real negative consequences of inequality. When you consider remedies, the trick is to weigh the possible negative consequences of your proposals against decreases in these negatives that they buy. Suppose that having better-paid college graduates and a few super-paid super-stars is just what one has to do to drive growth in a post-industrial economy. In that case, our attempts to reduce inequality might end up driving slower growth in median or sub-median compensation. Not just libertarians, but also Rawlsians, would prefer the status quo.

Henri Vieuxtemps 04.13.09 at 7:28 pm

It occurs to me that the word “inequality” doesn’t do justice here.

“Inequality” assumes some level of participation: we engage in some productive activity together, we divide the proceeds; if I get 80% and you 20%, then you probably have a reason to complain about inequality.

In this case, however, it looks like the bottom 80% do not participate in distribution of the proceeds at all, they are being paid a fixed amount, regardless of their productivity. This is not inequality, this is more like a form of slave labor.

StevenAttewell 04.13.09 at 8:06 pm

David Wright:

First of all, given that the incomes of doctoral grads fell 1.2% between 2000-2007 , masters 3.8%, and bachelor’s 2.7% in the same period, it’s unlikely to be the case that “the really important drivers of inequality are not the CEOs, but people like the readers and writers of crookedtimber.” The issue isn’t increasing returns to college education. (source: http://www.ombwatch.org/node/9305)

By contrast, if we look at long-term trends in terms of solely income, we see that not only is growth only occurring in the top, but even within the top, it’s just at the top. Between 1979 and 2005, the poorest fifth of households increased their post-tax income by 6.3% (only .24 of a percent per yer), the middle fifth gained 21% (.8% per year), the top fifth by 80% (3% per year)- but within the top fifth, the top 1% gained 228% (about 9% per year). (source: http://www.epi.org/publications/entry/ib239/) This is far too narrow a phenomenon to be explained by college education – this is the CEO problem.

Moreover, comparing this to the more robust and robustly shared income growth in the 1945-1973 period, I don’t think there’s much empirical evidence for the case that attempting to redistribute will make things worse. For 4/5ths of the population, it’s already “worse,” and the growth thing isn’t very persuasive when you’re not getting any return on growth.

David Wright 04.13.09 at 9:03 pm

Steven Attwell @ 21:

Your 2000-2007 statistics are throw-away, partisan fodder; this isn’t about Bush administration policies, it’s about broad trends over the last 40 years. I presume you don’t really need to be convinced, but anyone who does can easily find out that the real incomes of those who have gone to college have increased by about $10K/year over that period, while the incomes of those who haven’t have pretty much not changed at all, just as I asserted above. (The picture is even more stark when you look at total compensation, since it’s the college grads who get the good benefits packages.)

Your second paragraph simply illustrates precisely the problem I pointed out in the original post: it generates ever larger income numbers by looking at ever smaller slices of the population. To see the effect a change on broad-based measures of inequality like the Gini coefficient, you need to weight the income change by the numer of people it affects. That’s why a “mere” 20% real increase in the incomes of millions of college graduates can outweigh a 300% real increase in the incomes of CEOs. By choosing the ratio of the 99th percentile to 50th percentile as your metric, you have simply defined away the possibility that broader contributors to inequality can play a role.

Finally, I’m not sure what “redistribution” in the 1945-1973 period you refer to. Government spending as a fraction of GDP has been pretty constant for the entire post-war era, the wealthy contribute a larger fraction of government revenue after 1973 than before 1973, and government transfer payments represent a larger fraction of that spending after 1973 than before 1973. Perhaps you refer to top income brackets of 90% during that early period, but given what I just pointed out, it’s hard to argue that those higher brackets correlated with more redistribution.

I actually don’t think tax brackets had much to do with rising inequality, but someone who did could well argue that what happened was that the elimination of those high brackets incentitized high earners to work harder, creating more wealth for themselves but also more income for government to redistribute.

Warren Terra 04.13.09 at 9:03 pm

The per-household chart is great, but is there a per-worker version?

A reflection of the distribution (beyond just median-vs-mean) could also be interesting.

Barbar 04.13.09 at 9:25 pm

To put a point on it: the really important drivers of inequality are not the CEOs, but people like the readers and writers of crookedtimber.

Household incomes at the 80th, 90th, and 95th percentile have all increased relative to the median in the past few decades, with larger increases the higher up you go. For example, the ratio of the 80th percentile to the median was 1.7 in 1967 and 2.0 in 2003.

I think David Wright is correct to say that the 99th percentile is not the only number to track. Ideally there’d be some authoritative paper out there breaking down the causes of the inequality shift.

Marc 04.13.09 at 9:42 pm

David: the average income of the top 1% of households rose from ~300,000 to ~ 1,200,000 on average over the period illustrated on the graph. We know that the income of the median worker barely budged. Distributing that increase evenly over the entire population would amount to raising the average by 9,000 a household – indicating that the increase in wealth in the top 1% is indeed at a scale which is important for the median worker. Take a company with 100,000 workers. When the pay of top executives is modest then their salaries don’t impact the average worker. When they get paid 200 million dollars – the company is choosing to do that instead of paying the average worker 2,000 dollars. That matters in the lives of ordinary people in the way that a 2 million dollar salary (or 20 dollars a head) would not.

The greed of the very rich has become consequential. You claim “the elimination of those high brackets incentitized high earners to work harder.” I say “the elimination of those high brackets incentitized the wealthy to redirect the rewards of productivity from the workers to the parasites at the top.”

Market fundamentalists have to face the fact that their God has failed, just as Marxists did before them. The sooner the better for all of us.

Warren Terra 04.13.09 at 9:57 pm

As with all fundamentalists, their God Cannot Fail; It Can Only Be Failed.

scarpy 04.13.09 at 10:16 pm

Help me out here. The second chart doesn’t actually say that GDP per family and median household income were roughly equal in dollar terms in the years before 1980, right?

It just tells us about the ratio of each variable to its 1979 value, and reveals that those ratios were in sync through about 1980 and then diverged?

Just want to make sure I’m reading it right.

MarkUp 04.13.09 at 10:21 pm

David Wright

~”it’s about broad trends over the last 40 years. I presume you don’t really need to be convinced, but anyone who does can easily find out that the real incomes of those who have gone to college have increased by about $10K/year over that period,”

Not to put too fine a stroke to it, but could you possibly delve a bit deeper in the that pot of paint? Are you saying that broadly speaking that I, my wife and most of those we know [all with college educations] have gotten a raise of about 80k during the GW Bush tenure or a roughly 400k raise over the past 40 years [or a percent thereof]? While I do know some very wealthy folk, and have lived and been employed for those 40 years with degrees for the best part of them … I see neither as have happened, broadly speaking of course.

Thomas 04.13.09 at 10:22 pm

I thought the Census did publish post transfer post tax statistics. Isn’t that definition 14?

Barbar 04.13.09 at 10:45 pm

For informational purposes, in 2007, the average CEO compensation for America’s top 500 companies was $6.4 million; the top 4 clocked in between $100 and $200 million.

The increases in the top percentile are significant in overall terms.

The increases at the 80th percentile have also been significant (although less so) in overall terms.

Barbar 04.13.09 at 10:49 pm

MarkUp, David must have meant $10K total, not $10K/year, although only he knows for sure.

To clarify my last comment a bit, the top 1 percent should not be confused with the “CEOs of America’s biggest companies.” There are, what, a million households in the top 1 percent?

David Wright 04.13.09 at 11:27 pm

MarkUp @ 27: Sorry, my attempt to be clear with units apparently backfired. If you earned $30K/year in 1975 and $40K/year in 2005, your income increased by $10K/year; the rate of increase was only $330/year/year.

Marc @ 25: I appreciate your diving in with real, quantitative analysis! There are a few factors that make a careful quantitative analysis difficult, for example: Our income data is on households, but our education data is on individuals. Income volatility is very high for the highest income groups, so the income of the 99th percentile ratio depends strongly on the period you normalize over. The fraction of the population that falls into the college-educated category has increased significantly over the time period under study, but the fraction of the population in the top 1% category remains… 1%. I’ll try to dig up articles which actually compute the Gini coefficient under different scenarios, but I think from these sorts of back-of-the-envelope calculations it’s safe and fair to say this: neither the top-1%-income-explosion nor the college-education-effect is negligible, and neither is overwhelmingly dominant as a cause of inequality.

As an aside, I don’t entirely understand your tax incentivization argument. If I am greedy and I get to choose how the rewards of our common enterprise will be divied up between us, won’t saying that the government will take 90% of what I get cause me to choose to direct more to myself, to make up for that loss? In any case, please note that I specifically wrote that I personally believe tax rates are a red herring. (Since income data is pre-tax, they are in any case second-order effects.) I was merely pointing out that Atwell’s tax ideas a double-edged sword.

badpenny 04.13.09 at 11:36 pm

I would add to the pot of reasons for decreasing inequality is that the rich who saw their after tax incomes rise so much couldn’t possibly spend it all on more stuff. Instead, they started looking for higher and higher returns in the financial markets and looked to ever riskier assets.

In other words, huge surges in after tax income for the wealthiest of the wealthy has fueled the cycles of asset bubbles that seem to have become far more common place and substantial than they were in that 1945-1973 time period.

David Wright 04.13.09 at 11:45 pm

Babar @ 32 makes an important point. If your concern is really about the kind of super-star compensation (celebreties, hedge fund managers) that garners press coverage, you’re really talking about the top-0.01%, not the top-1%. The top-1% includes a lot of “merely” highly educated, in-demand professionals (medical specialists, corporate tax lawyers). I think it will even include upper-middle-class coastal homeowners realizing their appreciation, because the homeowner capital gains exemption is “below the line” in U.S. tax law.

gordon 04.14.09 at 12:42 am

“So what should we do?”

One option is to go and read the Economic Policy Institute’s “Agenda for Shared Prosperity”. I’ve been wondering why this detailed and moderate proposal (really a set of proposals) hasn’t attracted more broad support among US progressives. Or maybe it has and I haven’t noticed. Anyway, in a world rather short of positive proposals I think it stands out, and hope that maybe Prof. Kenworthy’s posts will refer to it.

gordon 04.14.09 at 1:02 am

In the US, the debate about how much tax the rich pay has been hopelessly confused with the story of the Bush tax cuts. See for instance here. This old post is also useful.

Will Wilkinson 04.14.09 at 1:14 am

I also worry the second chart is uninformative. Lane, can you produce a chart comparing GDP per capita to total compensation minus taxes plus transfers per worker?

Down and Out of Sà i Gòn 04.14.09 at 2:50 am

So you if someone stole $1,000 from someone making $1,000,000/y that would be less of a crime than if the $1,000 were stolen from someone making $10,000 a year? Aren’t citizen equal before the law?

Taxing (or stealing, if you prefer) everyone by a fixed amount is what’s know as a poll tax. They’re very, very unpopular. The last person who tried to institute one was Margaret Thatcher; she lost power over the fiasco.

To continue your example, imagine if you taxed $1000 on someone who was making $100 a year. They’re now out of pocket for $900. That’s why poll taxes often lead to riots.

And wouldn’t stealing $1,000 from someone highly productive who contributes $1,000,000 to the economy every year be more damaging than stealing the same sum from someone who hardly contributes to the economy?

No, it isn’t more damaging. Let’s leave aside the naive assumption that productivity is proportional to one’s income; a cleaner is more productive than your average AIG executive. You are going to get less random property damage from taxpayers over a progressive or proportional tax than from a regressive tax. Losing $1000 from $1,000,000 leaves $999,000, and we could all do well with a spare $999,000. Losing $1000 from $10,000 leaves $9000 – making it harder to feed yourself, let alone your kids (and what about their uniforms and textbooks too?). That’s the sort of situation where bricks get thrown at tax offices.

anonymous 04.14.09 at 2:56 am

Once again Catherine Rampell lays it all out.

anonymous 04.14.09 at 3:00 am

Federal, state and local tax combined:

anonymous 04.14.09 at 3:07 am

#39, to go even further–I say stealing $1000 from a rich person is a great way to make them even more productive. The simple reason is that the more wealth you have, the less incentive you have to work harder. So the best way to make rich people more productive is to make them poor, which means the top tax rate should really be 90% if we care at all about the productivity of our citizens.

:-)

Lee A. Arnold 04.14.09 at 4:40 am

I’m not convinced we can or should do anything about income inequality, but we should make taxation a lot more progressive.

Income taxes are not the only taxes. If you combine ALL U.S. taxes — federal, state and local — together, then the percentage distribution of taxes to income is nearly FLAT, down to the top of the bottom quintile. Most people apparently don’t know this.

Total taxation should be increased progressively up to a top 50% tax rate. A nice, easy number that everyone can remember. This figure can be approached by increasing the top federal income tax rates, and closing the loopholes.

It won’t hurt economic growth, it never did — except in chalk on a schoolroom blackboard. Most members of the economics profession have been acceding for decades to the clownish psychology and propaganda of the thinktank op-edders claiming that taxation of the rich hurts innovation.

In reality, the reverse is more likely: the evidence shows that economic growth has not been harmed by government spending for 200 years (see Peter H. Lindert, Growing Public: Social Spending and Economic Growth Since the Eighteenth Century, vol. 1.)

lane 04.14.09 at 5:22 am

Some interesting discussion here. Two brief responses for now:

ben a (#18): On mobility, see this post.

Thomas (#30): Yes, but those posttax data don’t go very far back in time.

virgil xenophon 04.14.09 at 6:23 am

RE: Bricks thrown thru windows@39: The last word on the art of taxation was offered by Cardinal Richelieu, who opined that the art of successful taxation was akin to the skill in the plucking of the Goose for it’s down feathers “with the minimal amount of hissing.”

gordon 04.14.09 at 7:53 am

By a curious coincidence, Economist’s View has posted again on tax incidence here.

Henri Vieuxtemps 04.14.09 at 8:08 am

I think the 90+% tax bracket/ incentive conundrum could be explained like this:

There is (and always will be) a small number of extremely avaricious (and unethical) individuals in any given population. These individuals analyze the social scene and find the vocations that would (under the circumstances) provide the best opportunity for them to achieve their objective. Currently, ‘business manager’ is certainly high on the list. These individuals are very difficult to compete against, and so people with genuine interest in business management have little chance to make it to the top.

Now, imagine that the society makes an effort to deincentivize these individuals. And not only from taking CEO jobs, but from polluting any legitimate profession: doctors, lawyers, stock traders, etc. This can be achieved by introducing something like a “maximum income”, or 100% tax bracket; and this would undoubtedly cause most of these asocial individuals (aka “top earners/producers”) to pursue illegitimate, criminal careers instead. Voila – suddenly everything is back to normal: managers manage, doctors heal, thieves steal. Everybody’s happy, case solved.

mpowell 04.14.09 at 9:28 am

I am curious to see what the stay tuned promise of this post will lead to. It has become nearly impossible to be politically informed with reasonable priors and not more or less agree with the content of this post. Figuring out the right approach, from either a policy perspective or a political perspective is quite challenging, I think.

gordon 04.14.09 at 9:55 am

Looking at the Citizens for Tax Justice site referred to by the recent Economist’s View post I linked to above, I find a report called “Do the Rich Really Pay Over a Third of Their Income in Federal Income Taxes?” (.pdf). An extract (quoting a recent report by the IRS):

“The IRS data show that the federal income tax rates paid by the highest-income Americans have dropped substantially since 2000, largely due to cuts in the tax rates on capital gains and dividends pushed through by the Bush Administration. While income from work (salaries and wages) is subject to rates as high as 35 percent, income from investments (long-term capital gains and stock dividends) is taxed at only 15 percent.

The IRS report shows that in 2006 (the latest year for which data are available), the 400 richest income tax filers paid just 17.2 percent of their adjusted gross income (AGI) in federal income taxes. That is down from 22.3 percent in 2000, and is less than half of the top statutory income tax rate of 35 percent. Almost 65 percent of the income reported by those 400 taxpayers consisted of capital gains and dividends subject to the preferential rates”.

Mikhail 04.14.09 at 11:16 am

You seriously must be kidding!

– Fairness? – so, basically, because YOU don’t feel it’s fair, let’s do something onto OTHERS? where exactly is fairness in that?

– GDP numbers? – since when should GDP translate directly into household incomes? as the economy changes from what it used to be 10-20 years ago, most of that growth goes towards sustaining itself, not to mention that the economy is now much more open, so a lot of that money goes abroad.

JoB 04.14.09 at 11:26 am

On the “Stay Tuned”-bit: if property increasingly is concentrated than the income of a happy few will always increase faster than is good for anybody, including themselves – high time that Soros/Buffett and the very rich liberals are barred from pontificating, & forced to loosen their more-leverage-than-the-US-President-grip on world economy.

Thomas 04.14.09 at 12:04 pm

Lane, the divergence happens during the period for which we have data. If you did the second graph just for 1979 and after, but with the post tax data, what would it look like? Would the divergence still be there?

Tom West 04.14.09 at 2:02 pm

As has been pointed out elsewhere, one simple explanation for at least part of the increasing household inequality over the last 40 years is that woman are working and now men and women both tend to seek mates who are doing roughly as well as they are. Suddenly household incomes of $100K vs $50K become $200K vs 100K, a 50K increase in household inequality without any one person earning more.

Does this ‘assortive mating’ become a matter for concern?

Tom West 04.14.09 at 2:09 pm

Another point – does the income numbers in the graph include income from assets? If that’s the case, a lot of the the increase is simply attributable to a higher return on capital over the last 40 years, since the higher income brackets almost certainly have disproportionately higher assets-based income compared to earned income.

Of course if this is the case, the increase may be disappearing quite rapidly in the current economic climate.

Rob Corl 04.14.09 at 3:30 pm

“Stealing” and “Fairness”.

If taxation is stealing, there should be no taxation. None. Everyone can “donate” or “contribute” what they think they need to to keep the roads, water, fire dept, police and military going. If you get in trouble with anything, good luck.

If we want “fairness”, then I want a shot at defining the rules. Breaking the rules is unfair. All men are created equal. You get zero dollars from any inheritance. We are all equal. That’s fair. You get zero advantage from the wealth of your family. We are all raised in a collective. That’s fair. We all get the exact same education, work the exact same hours and get the exact same pay. That’s equal, that’s fair.

ScentOfViolets 04.14.09 at 3:41 pm

What is the source of the inequality? This to me is the nub of the problem. Per the usual statistics, median income has risen less than one percent a year over the last 30 years. However, productivity increases measured in percentages have risen far faster. Assuming that the income distribution in 1975 was somehow more consonant with an idealized economic outcome, has the increase in productivity occurred disproportionately at the top, with median income earners increasing their productivity only slightly? Or have productivity gains occurred more or less equally across the board, with some other non-economic (in the neo-classical sense) factor redirecting the increases upward?

My own person feelings – which aren’t very liberal at all – is that it is the latter case. And while I have no problem with Kurt Warner or James Harrison making their millions, I do have a problem with people who are compensated large sums for apparently doing nothing or worse than nothing at all. I don’t think anyone can argue in good faith any more that a 27-year-old slacker living in his parents basement and working part time as a fry cook didn’t contribute more to the economic pie than Richard Fuld or Angelo Mozillo.

Thomas 04.14.09 at 3:59 pm

Lane, it looks to like like, using the after tax after transfer numbers, median household income has gone from $35,435 to $46,699 over the period 1979-2003 (in 2003 dollars), an increase of $11,264, while median household income under the standard definition (which I think is what you are using) goes from $38,649 to $43,318 over the same period (also in 2003 dollars), for an increase of $4,669. In other words, using post-tax numbers suggests much stronger median household income growth over the relevant period. What am I missing?

pianoguy 04.14.09 at 5:08 pm

The problem with the “top 1% of income earners pay 39% of all income taxes” etc. argument is that it’s circular. The fact of increasing income inequality, which of course will mean that those who earn more will pay a larger share of taxes, is used as a justification for income inequality: Just look how much tax the put-upon rich are paying!

As someone whose household income has been stagnant for several years – until this year, when it’s dropping significantly – let me state categorically that I would welcome the opportunity of paying more taxes on a higher income. As long as the marginal rate is below 100 percent, I don’t see any disincentive. A progressive tax is nothing more than a way of rewarding the system that made it possible to earn a great deal of money.

The idea that taxes are “theft” is a non-starter. Taxes are the cost of citizenship. In principle, I don’t resent paying them any more than I resent paying for groceries. The devil is in the details – what are we getting for our taxes? That’s a discussion worth having.

Tom West 04.14.09 at 7:20 pm

My own person feelings – which aren’t very liberal at all – is that it is the latter case.

Before I comment any further SOV, I’d like to know at approximately what point you think non-economic factors become significant in salary determination: $50K, $100K, $250K, 1M+? (Personally, I think it’s probably true at the $1M+, but I’ve heard arguments that no man is really worth more than ~$60K a year).

FoonTheElder 04.14.09 at 9:14 pm

I love it when the right wingers focus only on federal income tax and forget everything else. The tax system is stacked against the average American worker.

First, the income tax of capital gains is limited to 15%. Why is some millionaire get a tax break for investing in China or India or wheeling and dealing in stocks when many average workers pay more in income tax than 15%. Even Warren Buffett claimed that his tax rate was lower than his secretary’s

Then there is the great regressive flat tax called Social Security. It is 7.65% only paid by workers making under $100,000. The money they have overpaid in the system has been used to pay for tax cuts for the wealthy since the 80s.

Add the taxes paid by and for the average worker:

Federal income tax 15 to 34%

Social Security Tax -Employee 7.65%

Social Security Tax- Employer 7.65%

State Income Taxes-4 to 15%

Local Income Taxes 0 to 3%

State Unemployment Taxes- Up to 10% paid by the employer

Federal Unemployment Taxes- Up to 2% paid by the employer

Workers Compensation -Anywhere up to 5% paid by the employer

The wealthy pay a pittance for most of the unemployment, social security and workers compensation taxes. Why should capital gains be limited to 15% when income taxes on real work are much higher. The clowns who run our government are more worried about kissing Wall Steet’s fraudulent rear end and their billionaire buddies, than actually creating a fair tax system.

ScentOfViolets 04.14.09 at 11:05 pm

I don’t think there is a monetary set point; I’m merely pointing out that to the extent inequality is justified as a matter of cold economic value, few people have problems with it. It’s when value != compensation that a lot of people tend to get ticked off and that there is some sort of populist movement to redress the imbalance. And contrary to a certain brand of market fundamentalism, there are certain objective indicators that this is so. For example, if a person’s increase in productivity is 60% higher this year than last but their compensation remains flat, one could deduce that at some point this person is not being paid what they are worth.

lemuel pitkin 04.14.09 at 11:08 pm

if a person’s increase in productivity is 60% higher this year than last

How would you know?

ScentOfViolets 04.15.09 at 2:22 am

For a specific job you mean? Could you be more specific? If someone produces 100 blorgs in year 0 and 160 blorgs in year 1, that would be a productivity increase of 160%. Not all jobs could be so bluntly assessed of course.

Omega Centauri 04.15.09 at 2:44 am

I think maybe we need to think of at least two clases of utility. The first class, might be represented by the “living wage” concept, an amount of income which provides a tolerable living. After tax income above this level, can be spent on luxuries or invested in an attempt to secure greater future income. Clearly the marginal utility of a unit increase in income to an individual or family is dramatically different in the two cases. I think a good case might be made for the luxury utility to be similar to the LOG function. That would imply that an increase from say $.5M per year to $1M/year would have roughly the same effect as an increase from $100M to $200m. But, clearly the cost to society of the later is much higher. If you take that to be the case, then the effect on the very rich of a unit change in wealth is pretty small. If I woke up tommorow to the new that I won $100M or to the new that I won $1B, I doubt my reaction would differ much.

lemuel pitkin 04.15.09 at 2:49 am

Not all jobs could be so bluntly assessed of course

Nicely understated. Matter of fact, I reckon that there is hardly any blorg in a modern economy whose marginal output can be ascribed to one person’s (or one factor’s) contribution. If we had a productivity-o-meter, this whole discussion would not be taking place.

ScentOfViolets 04.15.09 at 3:25 am

I beg to differ[1]; exorbitant executive pay has been justified on the grounds that these people are ‘worth’ just that much, i.e., that is they are said to provide a rather large added value.

But if this is the case, how is this mysterious ‘added value’ measured? Iow, we know that there have been productivity gains of businesses as a whole by a certain reckoning. How do we know that the executive class are the ones responsible for these gains? Other than their say-so, of course. Especially given [1] in other parts of the large enterprise which are susceptible to such crude measurements.

[1]blorgs can be any part of a product or process of course; we’re not reduced to measuring only those outputs which are essentially handicrafts produced by a single person.

lemuel pitkin 04.15.09 at 3:57 am

You beg to differ, and yet it seems we agree after all.

My suggestion is that real-world production can be better modeled with a Leontief function, where factors are combined in fixed proportions and so the entire marginal product can be economically attributed to any of them. The division of output is then the result of a bargaining, or more broadly social, process.

Thomas 04.15.09 at 1:20 pm

OK, so I ran the calculations using the handy online BLS inflation calculator (which I think uses the CPI-U, not CPI-U-RS, but probably close enough for our purposes), and, using the numbers from definition 14 I described in comment 57 above, it looks to me that in 2003 the median family income in 1979 dollars was 1.3x the median family income in 1979. So, by my calculation, the divergence in the second graph would be much less sharp if we use the best definition of income. Am I missing something?

Tom West 04.15.09 at 8:49 pm

I’ve never been quite comfortable with current executive pay levels, but I’ve also not been able to understand why owners and stock holders are willing to pay that much (and from what I have seen, it’s not just that the game is rigged by the boards, private owners seem to feel that their executives are worth similar amounts and that money is coming from their own pockets.)

I find it hard to believe that no company has succeeded in paying reasonable executive compensation and been rewarded for it without others following suit. Could the market have failed so thoroughly?

My own guess is that owners, stock holders, and those that companies must deal with to survive tend to use compensation as a metric for competence. Paying your executives what we would consider reasonable salaries signals to everyone that your executives are incompetent. (After all, if they were competent, they’d go elsewhere.) For businesses that depend on trading partners, that could be fatal.

One correlation that I have heard is that the compensation versus company size had remained roughly constant. It’s that companies are many times bigger than they used to be. Maybe you pay in relation to responsibility rather than to competence. Do supervisors of bigger school board earn more than for the same job in smaller school boards?

Henri Vieuxtemps 04.15.09 at 9:26 pm

Tom, in privately owned companies – isn’t the CEO usually (if not always) the owner himself? Or owner’s son?

The CEO of Berkshire Hathaway is paid $100K/year. Teh guy likes to manage businesses, you see; that’s his idea of fun. According to wikipedia “…in 2007, he earned a total compensation of $175,000.” It’s a very big company, plenty of responsibility. It’s also a very successful company. Unless, of course, you measure success by the amount of dough funneled into executives’ bank accounts. By that measurement it’s a total failure.

lane 04.16.09 at 4:45 pm

Thomas (#52 and 57): Using definition 14, the rise in median household (rather than family) income is about $3,000 more with those data. That changes the picture, but only a little.

Daryl McCullough 04.16.09 at 5:11 pm

Tom West writes:

I don’t think it’s mysterious at all. For better or ill, the CEO can have a huge impact on a company’s profits. Hiring one CEO rather than another can make billions of dollars difference in the company’s bottom line. So it’s a false economy to try to save a few million dollars on CEO salaries. That doesn’t mean that spending more on CEO salaries is worth it, but it means that within a huge range of CEO salaries, getting the best CEO is higher priority than saving money on CEO salaries.

Righteous Bubba 04.16.09 at 5:23 pm

I agree with this and the rest of your comment, but I think the past year has shown that CEO search committees could be doing a better job.

So: we can’t guarantee an efficient and rational market for CEOs, but we can guarantee an efficient use of their salaries if the government takes a large portion of it.

Righteous Bubba 04.16.09 at 5:27 pm

Or of them. Whatever, smartypantses.

Thomas 04.17.09 at 2:08 am

Lane, yep–somehow I must have written down the wrong number on definition 14 income, which led me astray. (In case anyone cares, $46,699 above should be $43,629.) Thanks.

Arion 04.18.09 at 11:10 am

To a great extent, salaries in the finance/CEO sector are driven by a kind of herd phenomenon: If your competing corporation has a 5 mil CEO, then you better get one too. It’s glam to have one of those. Naturally the CEOs themselves hardly mind. I’m convinced the CEO world looked over at entertainer and pro athlete salaries and figured “if them, why not me? I contribute as much to the body politic as Madonna’. It’s a classic market oriented fallacy to suppose that CEOs are primarily motivated by dollars. by and large the motivation is the challenge of doing the job well. Compare the very modest salaries of Gineen at ITT or Engine Charlie Wilson at GM. They did as well or better than Jack Welch.

Comments on this entry are closed.