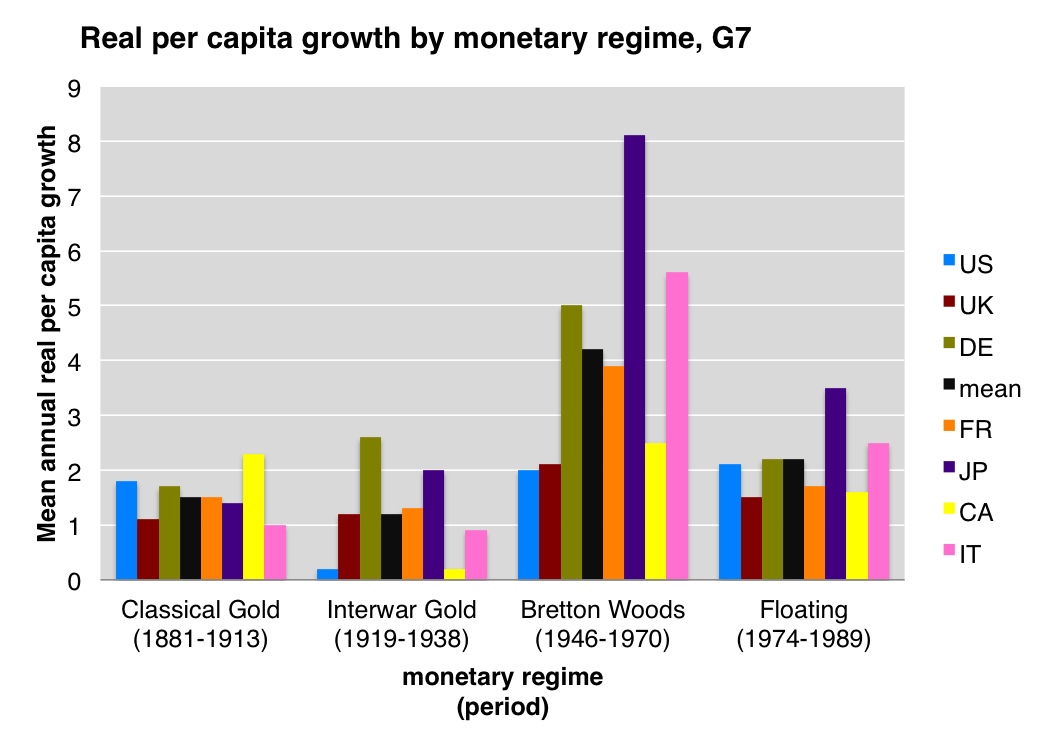

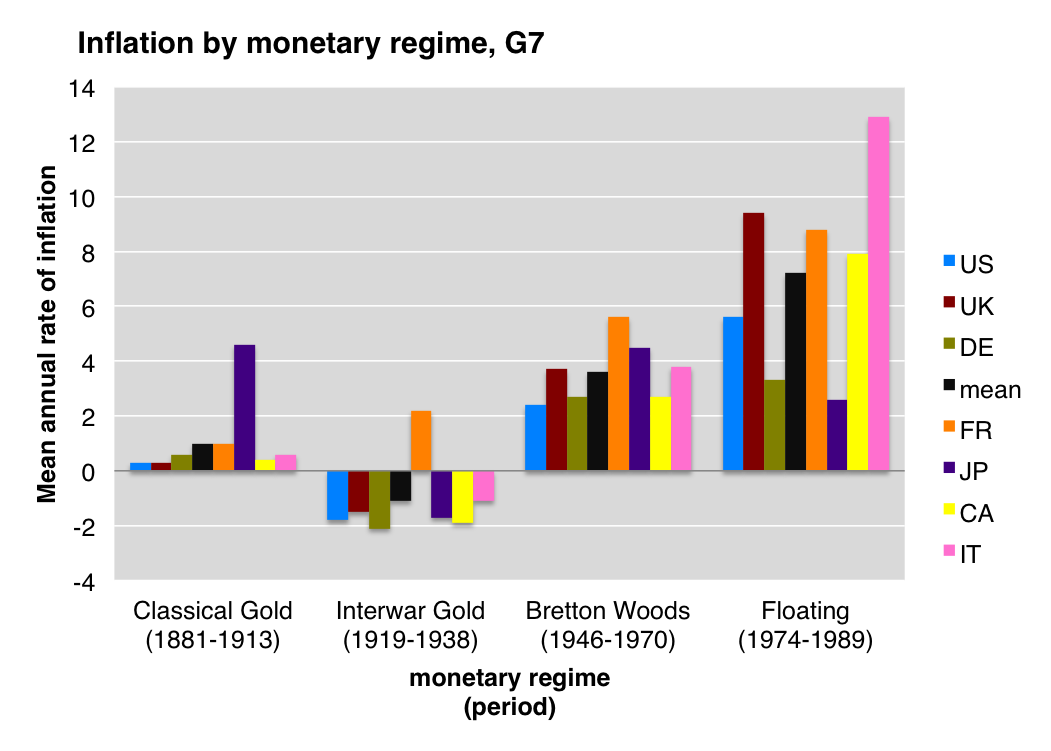

Was the gold standard a golden age, or a gilded one? How does it compare to later monetary regimes? I mean, we know the gold standard was terrible for the US, but what about other countries? I know you want to know, without having to dig in data appendices, so I made you some charts. Because I love you that much. (But not enough to extend the floating exchange rate regime data down to the present; that’s actual work.)

Data from table 1, Michael Bordo, “The Gold Standard, Bretton Woods and other Monetary Regimes: An Historical Appraisal,” NBER working paper no. 4310.

{ 36 comments }

Salem 04.09.13 at 8:25 pm

Part of the problem here (and indeed with econometrics generally) is that the ceteris is so very far from paribus. It’s very hard to know how much of the differential in growth rates to put down to the monetary regime, and how much to put down to other factors. Given that money is neutral in the long-run, my prior is to say that the monetary regime doesn’t matter much over a 25-year period. Another person may disagree – the author appears to, but is reluctant to quantify. It’s very hard to persuade with data such as these; you need “thick,” theory-laden explanations.

The other problem, of course, is categorization. The author himself attempts to draw a distinction between the pre-convertible and convertible Bretton Woods standards. But more than this, different countries within those time periods handled monetary policy very differently. Consider the differences between the US and the UK in how they handled the interwar gold standard; were they really following the same monetary policy in any real sense? Or look at how the 1974-1989 period is lumped together as “floating” – not a monetary policy at all, but rather a statement that no kind of gold standard is being applied. Germany and Italy were obviously not following the same monetary policy during that period – and indeed witness the chaos now they are forced to.

rf 04.09.13 at 8:30 pm

But is the argument fair though, that the growth we see in Latin America, parts of Africa, China, India etc, couldn’t have occurred under Bretton Woods? (Or should I read the article? Also not sure what the CA is in the charts..could be China?)

rf 04.09.13 at 8:34 pm

..actually would be Canada I guess

In the sky 04.09.13 at 8:41 pm

Indeed. I’d nearly go so far as to say that summary statistics like this are all but useless. All else equal, growth would be higher for 1946-1970 than 1975-1990 just because of Solow convergence. And that’s before we get into things like taxes, trade, and education levels.

Steven Vickers 04.09.13 at 8:45 pm

Given that the top-four performing economies by GDP growth in the 1946-1970 period were, in order, Japan, Italy, Germany, and France, would the main takeaway from the graph be that after you are recovering from a devastating war taking place on your territory, your GDP tends to grow relatively rapidly?

Kindred Winecoff 04.09.13 at 8:59 pm

Great charts. I assume they are mostly directed at me, so I’ll start by admitting that I overstated the case in the other thread: it wasn’t just white male American labor that benefited from BW. Mostly-white male labor in already-industrialized societies did well too. I’ve read Bordo (and Eigengreen) on this and I have no quibbles with their work. And you might have no disagreement with what follows, but I see a lot of folks wishing for the glory days without really understanding what entailed, so here’s a full fleshed-out take of my view:

What’s not clear (to Bordo/Eigengreen, or me) is how much of BW’s success was due to re-industrialization following the war, and how much to the institutions themselves. Standard macro would suggest a lot of the latter, as under-utilized productive capacity was put to productive use and agglomeration effects took hold. What is clear is that BW was exclusionary: pre/quasi-industrial economies had a very difficult time modernizing under that system. Hence ISI, NIEO, Singer-Prebisch, Wallerstein, etc. The legacy of that exclusion has been severe and long-lasting in many of these places, as were many of its effects at the time. It’s significant (to me anyway) that the internationalist left — as opposed to domestic labor movements in industrialized countries — was strongly opposed to BW at the time.

It’s also clear, or at least likely, that BW wasn’t going to last given the configuration of domestic political institutions in the principal BW countries. Remember that European convertibility wasn’t re-established until 1958, and the two-tier gold structure began in 1968. So we’re really only talking about 10 years where “BW” was actually BW. The eurozone did well for a decade too… doesn’t mean it was built on a solid foundation. Growth was strong from 1945-1958 — as strong or stronger in most places than it was from 1959-1968 — which indicates (to me) that re-industrialization was playing a big role in the positive growth experience. I do think BW policy commitments had a positive impact on domestic distribution in the countries which experienced growth, but global inequality spiked during this period.

Capital controls may have been good at preventing crises in the Core, but it also meant little investment in the periphery. It meant that export-oriented industrialization, perhaps the biggest development success in human history (albeit with some real downsides), was not viable as a global development strategy. As I said in the other thread, dependency theory works pretty well during the BW period; much less well after.

From 1945-1970, the US went from 50% of the world’s manufactures production to 20-25%, where it has mostly stayed ever since. That 25-30% was distributed among Western Europe and Japan… good for them, not good for labor in the South. The overall pie got bigger… good for US labor. But it was based on a contradiction that the US could somehow simultaneously provide a growing world economy with sufficient liquidity and keep parity with gold. Keynes knew this was a lie. Something had to break, so it did.

So if we could get BW back, that would (in practice) mean preventing EOI countries from manipulating the balance of payments to boost domestic employment. This would probably good for Western labor, true, and it would probably be bad for Western capital, true, and it might help mitigate certain types of financial crises, true, but the cost would be pretty high. And, given that there is little re-industrialization to capture, the growth experience would almost certainly be worse than it was from 1959-1968.

BruceJ 04.09.13 at 9:13 pm

It would appear that the very best way to gain economic progress under the Bretton-Woods regime was to get your industrial sector blowed up real good by the 8th or 13th Air Forces, then rebuilt by the Allies.

More seriously, how much of that GDP growth under BW was less the actual agreement and more about sustained increases in demand post-Great Depression + WWII? How do you tease out the effects of the BW monetary scheme from the enormous overall uptick in demand?

LFC 04.09.13 at 9:56 pm

KW:

I do think BW policy commitments had a positive impact on domestic distribution in the countries which experienced growth, but global inequality spiked during this period.

But doesn’t one have to trace the North-South divergence in growth rates back to the 19th c., which is when the divergence really opened up? (I know, a fair amt of the global South was colonies well into the 20th c., but the general point stands, I think.)

What is clear is that BW was exclusionary: pre/quasi-industrial economies had a very difficult time modernizing under that system. Hence ISI, NIEO, Singer-Prebisch….

One of Prebisch’s main arguments iirc had to do w declining terms of trade for primary commodity exports vs. manufactured exports. I mostly forget the causal story he gave, but did it have all that much to do w fixed exchange rates and the dollar-gold connection? That isn’t my (admittedly rather vague) recollection. Yes, I could look it up, I suppose…

Somewhat OT in that it relates only to the U.S., but speaking of charts, this one (I forget where I first saw it mentioned, prob. on a thread here) is rather striking:

http://www.dissentmagazine.org/blog/the-arc-of-inequality

Eric 04.09.13 at 9:57 pm

Ceteris paribus arguments are all totally legit – which is one reason it’s instructive to note the floating era is also better than the gold standard.

marcel 04.09.13 at 10:20 pm

The long run inflation figures are interesting, but I’d be at least as interested in the mean (absolute value of the) year-over-year change in the price level. If it is going up and down by 5%/year, that can be as disruptive and make planning at least as hard as a steady 5% increase each year, but it will not show up in the long run figures.

The period chosen to present inflation for the classic gold standard (1881-1913) is almost cherry picked for price level stability. In the US, and I believe internationally, prices fell from the 1870s through about 1896 (esp. rapidly from about 1892-1896), following the Civil War inflation, and then began climbing again from about 1896 through about 1921, when the Fed instigated its first ever (I believe) recession to purge the system of the WW1 inflation.

Thus the long term inflation of the 2nd half of that period balanced out the long term deflation of the first.

I used to know this bit of history quite well (c. 25-30 years ago), and have not looked it up for this post, so perhaps my middle-age memory is playing tricks on me, but this is my story, and I’m sticking to it (until someone shows me I’m wrong)!

5566hh 04.09.13 at 10:22 pm

Wouldn’t it be more useful to look at household income rather than GDP? After all, GDP can rise a lot without household income rising much at all.

Eric 04.09.13 at 10:37 pm

Somewhat OT in that it relates only to the U.S., but speaking of charts, this one (I forget where I first saw it mentioned, prob. on a thread here) is rather striking:

Yes, and in light of that it’s worth noting that the CIO, especially, lobbied hard for Bretton Woods to be adopted in the US.

Eric 04.09.13 at 10:39 pm

marcel: If it is going up and down by 5%/year

Would you accept standard deviations? Bordo has them in table 1, at the link – I’m nearly sure that’s an ungated paper. And sure, the dates are as much as cherry-picked to make the classical gold standard look good – so given that it looks bad, it must have been pretty bad.

Also, there is a case to be made that you can’t say there’s an international gold standard until a certain share of these countries are on it.

Ed 04.09.13 at 10:40 pm

The first chart tracks fairly closely international discovery of major oil fields.

Eric 04.09.13 at 10:43 pm

Wouldn’t it be more useful to look at household income rather than GDP? After all, GDP can rise a lot without household income rising much at all.

Yes, though I don’t know of income data for the c19 and would be happy to be pointed to it.

Eric 04.09.13 at 10:44 pm

would the main takeaway from the graph be that after you are recovering from a devastating war taking place on your territory, your GDP tends to grow relatively rapidly?

…especially if you’re receiving big loans from the World Bank (France) and the US (everyone)—which is a major part of what “Bretton Woods” meant…

Davis X. Machina 04.09.13 at 10:57 pm

I admire your temerity in attempting to refute a theology with charts.

Eric 04.09.13 at 11:13 pm

theology

Freud had a different explanation.

Kindred Winecoff 04.09.13 at 11:18 pm

@LFC:

“I know, a fair amt of the global South was colonies well into the 20th c., but the general point stands, I think.”

I actually think it’s a pretty big distinction. Independent countries (esp in Latin America) successfully pursued export-led growth in the 19th c and into the 20th until the Depression killed global demand. Capital was mobile due to the fact that there was no monetary independence, so capital could (and did) flow from North to South. Colonies weren’t able to do the same b/c of the imperial preference trading system which gave monopsony power to the metropole, so there was a divergence between colonies and non-colonies.

Post-WWII, US was committed to the end of (formal) imperial competition and the preferential trading system it involved (this is prominent in both Wilson’s 14 Points and the Atlantic Charter). Such a system could lead to broader global convergence, except:

“One of Prebisch’s main arguments iirc had to do w declining terms of trade for primary commodity exports vs. manufactured exports. I mostly forget the causal story he gave, but did it have all that much to do w fixed exchange rates and the dollar-gold connection?”

You’re right about Prebisch, but you miss the corollary: in the face of a secular decline in the terms of trade for primary commodities exporters, development becomes harder because domestic capital becomes scarcer: more and more is dedicated to producing commodities for exchange, less and less goes to modernization. Development requires the accumulation of capital stock, not the deterioration of it. You can’t overcome this secular decline when trade is balanced; you need to run current account surpluses — i.e. capital account deficits — for awhile to get enough capital to invest in modernization. Under a fixed exchange rate system it’s difficult to do that. With capital controls in force it’s even harder.

There are two solutions:

1. Use commodity power as bargaining leverage to reverse the terms of trade decline. The Group of 77 tried this, and it didn’t work: http://www.g77.org/doc/algier~1.htm

2. Shut off from the global economy and mobilize what domestic capital you have towards ISI. This can work for awhile, but tends to eventually calcify for political economy reasons.

Once BW broke, you can earn capital via exchange rate devaluation and increased exportation. You can use this earned capital to modernize without accruing a large debt burden. I.e., the export-oriented industrialization strategy which had been viable in the 19th century became viable again.

The result was a (pre-tax/transfer) redistribution from the BW status quo ante: conditional on politics, capital in the North and labor in the South benefited. Hence the rise in pre-tax/transfer within-country inequality throughout the North — and the decline in union power… a consequence less than a cause, in my opinion — and the decline in between-country North-South inequality.

Local politics determined how all this was distributed.

Anyway, that’s the simple version.

LFC 04.10.13 at 12:25 am

Kindred @19

I wrote a longish reply and then hit the wrong keys and it vanished. Short version: I basically follow what you are saying here; am wondering whether this is — esp. w/ reference to the main pt re the distributional and other effects of the ‘end’ of BW — the standard consensus IPE view, or something more particular to you? (I assume the former but am not absolutely sure.)

In the sky 04.10.13 at 12:32 am

For those interested, James Hamilton of UCSD has some graphs that require fewer assumptions to believe:

http://www.econbrowser.com/archives/2005/12/the_gold_standa.html

http://www.econbrowser.com/archives/2012/02/why_not_abolish.html

Kindred Winecoff 04.10.13 at 2:48 am

@LFC

I’m not sure there’s a “standard IPE” view on this, insofar as mainstream IPE is concerned mostly with comparative statics rather than dynamics. E.g., I don’t see many IPE folks tying increased US inequality (or the rise of neoliberalism) from 1970-now to the collapse of BW. And I think the standard IPE view of dependency theory is that it is just plain wrong, not that it was more-or-less right under BW but then stopped being right when BW stopped existing. (In fact, I heard Milner say something like that at ISA just last week.)

Also, IPE tends to be eurocentric so they/we spend a lot more time parsing the experience of the West — like the charts in the OP — than parsing what was going on in the “Rest”. As I’m sure you know, I think this is a fool’s game: the experience of the West is contingent upon the experience of the Rest (and vice versa).

That said, if I told this story to most IPE folks I doubt they’d see much that was objectionable in it. I’m just not sure a lot of them would construct it on their own without a decent amount of prodding. I could be wrong about that.

But most IPE folks aren’t surprised by the eurozone crisis (unlike the subprime crisis); Oatley called it before the euro even came into being (in his dissertation, later published by U of Mich Press). One of the most well-known IPE books is Simmons’ *Who Adjusts?* which describes the politics surrounding the end of the interwar gold standard. The same general framework could fairly easily be applied to BW, and maybe it has. But I’m not aware of a general treatise on it.

LFC 04.10.13 at 6:12 am

@Kindred

thanks

reason 04.10.13 at 8:30 am

Steven Vickers @5

“Given that the top-four performing economies by GDP growth in the 1946-1970 period were, in order, Japan, Italy, Germany, and France, would the main takeaway from the graph be that after you are recovering from a devastating war taking place on your territory, your GDP tends to grow relatively rapidly?”

So what about the interwar period then?

Steven Vickers 04.10.13 at 12:07 pm

So what about the interwar period then?

I’m not trying to defend the gold standard here, which I think Eichengreen and others have convincingly demonstrated greatly exacerbated the Great Depression. I’m merely pointing out that when you compare BW to floating, you have four countries (JP, IT, DE, and FR) which are substantially higher and three (US, UK, CA) which are much closer, and those groupings tell you something meaningful. To the degree that the graphs are presented primarily as an anti-gold standard argument, the fact that both BW and floating look better than gold is also meaningful (as Eric points out at #9).

James Wimberley 04.10.13 at 3:58 pm

Reason in #24: “So what about the interwar period then?” WWI damaged the industrial base locally in Northern France. Battlefields elsewhere (Veneto, Galicia, East Prussia) were not SFIK in industrial areas. The two cataclysms were very different. WWI killed a high proportion of young men, so could lend itself to a Schumpeterian explanation of interwar stagnation in Europe as a result of reduced youthful dynamism. Unfortunately that clashes with the comparatively worse performance of the USA, with proportionately lower casualties.

Billikin 04.10.13 at 6:37 pm

My first reaction to those graphs is Lies, Damned Lies, and Statistics. How can we lump together the 1920s with the 1930s, the 1970s with the 1980s? After WWII, how can we lump the defeated Axis powers with everybody else? The same goes for Germany after WWI.

ezra s abrams 04.11.13 at 1:03 am

Why do Economist always turn arguments about the economy into economics ?

far as i can see, gold std is probably a lot less important the FDIC, good medical care, etc.

The fact is, technological progress is a lot more important then things like the gold std; the clearest current example is the (very scary) projected cost of healthcare.

This is absolutely NOT an economic problem; it is a technological one;

I mean, why does it cost more then about 1,000 dollars for open heart surgery ?

Once you start asking “unreasonable” questions like that (another great example is , since google is so bad, why are they so popular) you see that the answer is technology.

musical mountaineer 04.11.13 at 2:04 am

I’m glad to see that the ceteris paribus caveat came up right away. There are other factors which need to be considered, namely:

* The Bolsheviks were recently victorious in the Mexican Civil War, with major repercussions for international stockholders in the Australian slave trade.

* France’s successful manned mission to Halley’s Comet in 1933 inspired a surge of American and British patriotism which clearly bolstered textile and agricultural markets.

* In 1931, the Catholic Church was established as the official religion of India. The resultant ban on heterosexual marriage in Indonesia and Tahiti had profound demographic consequences throughout East Philadelphia.

Here’s what I’m getting at: according to O’Brien at the Atlantic, the money supply in America was on the gold standard between 1874 and 1933. As I’ve demonstrated above, it is possible to get farther from the truth than that. But it’s bound to cause confusion.

I’m open to the argument that the gold standard is politically and socially impossible to maintain, because the temptation of fiat money is always far too strong to resist. I’m open to the argument that, if you’re going to have fractional-reserve banking where the required reserve is pathetically small, and most banks aren’t lawful enough to carry even that, then you probably should drop the pretense that the notes issued are redeemable in gold, because it can only cause panic when depositors realize the gold was never in the vault. I’m even open to the argument that a highly-elastic money supply backed by nothing whatsoever is a good thing overall, though the points against that argument are enough for a hundred threads.

But you can’t say we have a historic period of gold-standard banking that is susceptible to economic analysis. We don’t; certainly not in that time-frame.

reason 04.11.13 at 8:05 am

Billikin,

“After WWII, how can we lump the defeated Axis powers with everybody else? The same goes for Germany after WWI.”

We didn’t – they are graphed seperately. I agree that a timeline (5 y moving averages for instance) would have been more informative.

reason 04.11.13 at 8:14 am

ezra s abrams @28

Strange comment.

Firstly, the linked article points to differences in periods of recession or depression, when lots of resources sit around in idleness – a complete waste of productive potential you can never get back (ignoring what it does to families and individuals). This article points out that this cost was not compensated by stronger average real growth (au contraire). And it makes sense to point this out when a significant political force calls for the return of such nonsense.

“I mean, why does it cost more then about 1,000 dollars for open heart surgery ?”

1. more yes – A very lot more

2. how is this not an economic question? – it costs a lot more because people are paid a lot to do it.

Grant 04.11.13 at 3:15 pm

But not enough to extend the floating exchange rate regime data down to the present; that’s actual work.

Challenge accepted: Updated version of your charts here.

In brief: Inflation in “Floating” regime period falls, as does GDP (although to a notably lesser extent).

Eric 04.11.13 at 5:17 pm

Outstanding, Grant. Thanks very much.

Billikin 04.12.13 at 1:07 am

Billikin,

“After WWII, how can we lump the defeated Axis powers with everybody else? The same goes for Germany after WWI.â€

Reason: “We didn’t – they are graphed seperately. I agree that a timeline (5 y moving averages for instance) would have been more informative.”

But the reader has to be aware of the differing conditions that make them different. They are presented as though the differences are random.

JW Mason 04.15.13 at 3:32 am

Obviously eras differ on all sorts dimensions, so it’s moronic to think you can judge the goodness of a particular institution simply by comparing growth rates between periods. This could just as well be interpreted as evidence on the merits of steam vs electricity, or mass migration, or parliamentary democracy, or any of a thousand other differences between the worlds of 1890, 1920, 1960 and today.

If people want to learn something about the actual economics of the gold standard, One good place to start is Robert Triffin.

reason 04.15.13 at 10:34 am

Grant @32

What is interesting is how the period of floating exchange rates has equalised long term per capita growth rates compared to any previous experience. In fact to a truly amazing extent. One suspects that this is not really about the exchange rate regime, but about the disappearance of capital controls.

Comments on this entry are closed.