Apologies for extended absence, due to me teaching a Coursera MOOC, “Reason and Persuasion”.

I’m moderately MOOC-positive, coming out the other end of the rabbit hole. (It’s the final week of the course. I can see light!) I will surely have to write a ‘final reflections’ post some time in the near future. I’ve learned important life lessons, such as: don’t teach a MOOC if there is anything else whatsoever that you are planning to do with your life for the next several months. (Bathroom breaks are ok! But hurry back!)

We’re done with Plato and I’m doing a couple weeks on contemporary moral psychology. The idea being: relate Plato to that stuff.

So this post is mostly to alert folks that if they have some interest in my MOOC, they should probably sign up now. (It’s free!) I’m a bit unclear about Coursera norms for access, after courses are over. But if you enroll, you still have access after the course is over. (I have access to my old Coursera courses, anyway. Maybe it differs, course by course.) So it’s not like you have to gorge yourself on the whole course in a single week.

We finished up the Plato portion of the course with Glaucon’s challenge, some thoughts about the game theory and the psychology of justice.

They say that to do injustice is naturally good and to suffer injustice bad, but that the badness of suffering it so far exceeds the goodness of doing it that those who have done and suffered injustice and tasted both, but who lack the power to do it and avoid suffering it, decide that it is profitable to come to an agreement with each other neither to do injustice nor to suffer it. As a result, they begin to make laws and covenants, and what the law commands they call lawful and just. (358e-9a)

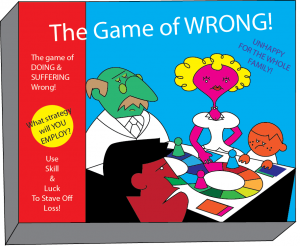

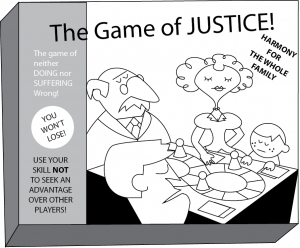

So I whipped up some appropriate graphics (click for larger).

And:

Point being: first game looks more fun. Gets good and hot! But the second, despite it’s apparently dull pattern of play, is really a remarkable achievement in the history of game design.

I like to have fun, in short. (I also did some good theory of justice as IKEA instructions parodies.)

For the final two weeks we’re reading some Jonathan Haidt, followed by bits from Joshua Greene’s new book, Moral Tribes: Emotion, Reason, and the Gap Between Us and Them [amazon]. My line is basically that Greene, as a forthright utilitarian, is a philosophically improved Jonathan Haidt – who is also a utilitarian, but reluctantly and, therefore, schizophrenically. In The Righteous Mind, Haidt spends a great deal of time abusing utilitarianism as a symptom of intellectual error – even of personal autism. Utilitarians are described as the sort of people who would open a restaurant serving only sugar. And then, more than halfway through the book we get this:

I don’t know what the best normative ethical theory is for individuals in their private lives. But when we talk about making laws and implementing public policies in Western democracies that contain some degree of ethnic and moral diversity, then I think there is no compelling alternative to utilitarianism. I think Jeremy Bentham was right that laws and public policies should aim, as a first approximation, to produce the greatest total good.

This contains the sum total of Haidt’s official argument for utilitarianism, and it puts his earlier attacks on utilitarianism in a strange light. He says he just wants utilitarians – rationalists generally – to be more open to appreciating human complexity. But, for the most part, his evidence that they are bad anthropologists and bad psychologists just is that they are utilitarians. Which he is himself.

Greene straights all this out by being much clearer about the following: if you accept Haidt’s basic picture of human nature; if you are a utilitarian; what should you advocate?

I’m not very trolley problem-positive, as a rule. I think it tends to get a bit silly. But Greene’s book is good. I was substantially won over as to the utility of these silly stories, not so much for thought-experimental purposes, but for actual cognitive science experimental purposes. I’m now convinced that asking people this stuff probably does show some stuff about how the brain works. (Of course, we don’t really know how the brain works. But you have to try, if that’s your job.) Anyway, the lesson for course purposes is: if you actually subscribe to a basically rationalistic ethical philosophy in which you think everyone should be pursuing the Form of the Good – that’s Plato, Haidt and Greene – you need to be clear that this is what you are doing, and how and why. That’s Plato (sort of) and Greene (sort of) but not Haidt.

I’m not just negative about Haidt, however. His first book, The Happiness Hypothesis, is a good example of how to do popular stuff right, I think. The Righteous Mind … I didn’t like so much. The politics stuff takes the author too much out of his areas of competence. But I didn’t end up really talking about the liberals vs. conservatives stuff much in my course. So I won’t go into that now.

{ 158 comments }

Lew Dog 03.28.14 at 6:39 am

What is this “justice” you speak of?

Anders Widebrant 03.28.14 at 9:18 am

I’ll take this opportunity to say that I’ve really, really enjoyed the course! I didn’t make time for the essay, but the lectures and the book are absolutely awesome.

The smallest of nitpicks: The course book was only just readable on my Kindle (without converting it, which both improved and reduced readability, and put a real dent in the justification bits). A point or two larger typeface would have made a huge difference.

John Holbo 03.28.14 at 11:53 am

Thanks. Yeah, I need to redo that old PDF, which was made before the days of Kindle or anything fancy like that.

mattski 03.28.14 at 12:57 pm

@ 1

Go to Kollege. Fine doubt.

Donald A. Coffin 03.28.14 at 2:28 pm

Looking forward to your reflections on teaching a MOOC. I suspect that they might be publishable in an actual peer-reviewed journal thingee, too.

TM 03.28.14 at 3:54 pm

According to Harper’s Index (3/2014), only 4% of MOOC students complete the course and 49% view no more than one lecture. Would you mind sharing your numbers?

Manta 03.28.14 at 5:10 pm

Shouldn’t the games of right and wrong have strangers as players, and not family members?

I would also like to read on your MOOC experience.

Maybe there will be a duel at dawn with Eric Loomis?

Main Street Muse 03.28.14 at 10:46 pm

MOOC question – how many students and how do you grade? Do the students participate in online discussion forums? Do you moderate those discussions? I am intrigued by the concept but cannot fathom how assessments can be done on student work.

jeffreyw 03.28.14 at 10:48 pm

Is there any way to download just the audio portion of the videos?

GiT 03.29.14 at 1:08 am

@MSM

If I recall correctly, John’s using peer grading.

John Holbo 03.29.14 at 1:56 am

“Is there any way to download just the audio portion of the videos?”

Unfortunately not. You’ll have to use Handbrake or something like that.

“According to Harper’s Index (3/2014), only 4% of MOOC students complete the course and 49% view no more than one lecture.”

As of this morning my numbers go something like this:

enrolled ever: 43966

accessed ever: 19526

accessed last week: 3415

I could dig out more details but that should do. In our first week we peaked at about 10,000 individual visitors. That fell off steady until finally plateauing around 3400.

I don’t know how many students will ‘complete the course’ yet, i.e. pass, but it will surely be in the hundreds, not thousands.

The Harper statistic is alarming because we have an immediate sense that these statistics would be very very bad in an ordinary university context. But this isn’t that. ‘Enrolling’ in a Coursera course is just signing up to get an email when the course starts. Or, if it’s started, clicking a box that let’s you look and see whether it’s interesting. Calling that ‘enrollment’ is misleading. It isn’t even conditional commitment, so if it fails to lead to real commitment much of the time, that’s hardly surprising, and not obviously a problem. And, once you are in, it’s obviously going to be normal for people to access only some of the content. How many people who visit Crooked Timber read our entire archive? 0%, right? Is that a problem? Not obviously. I’ve literally never heard anyone say that getting as many visitors to read your entire site as possible is important.

Half of the people who visit view only one lecture? I’m sure that half the people who click on ‘more product information’, or put stuff in their basket, don’t end up hitting ‘check out’. That’s not necessarily a bad thing, and if some gung ho capitalist were to sound the alarm: people aren’t serious about consuming! Many of them put things in their shopping basket and then don’t check out! … Well, that would be rather silly.

Some people won’t like the course well enough to want to watch very much of it. That’s natural. Some people will like it but not be up for 16 hours of viewing. Maybe they only want to watch 4 hours. Not to get all the-future-of-education-is-iTunes, students-will-buy-only-the-singles-not-a-whole-album, but if someone tells me they only watched my Euthyphro lectures, and liked them, but didn’t finish the course, I’m not too upset. There are reasons to force university students to take a whole course for credit. But that doesn’t mean that ‘did you take THE WHOLE COURSE?’ therefore becomes some sort of hallowed standard for seriousness, or an indicator of whether johnny is learning.

As to finishing the course, Anders says he liked it. I’m glad. Suppose he watched all 16 hours and read the book and all that stuff. But he decided not to take my little auto-graded mcq quizzes or write the peer-assessed essay? Well, then he doesn’t pass. Is that a problem? Does it show a lack of commitment on his part, or a failure on my part to engage him as a learner? Not really.

Suppose I tried to prove that MOOC’s rule and traditional university courses drool by citing just average enrollments. MOOC’s get 10 times the average enrollments, I’m sure. That doesn’t mean MOOC’s are, on average, 10 times better than traditional classes, because MOOC enrollments aren’t comparable. We aren’t comparing apples to apples. But the same goes for completion rates. The logic of MOOC completion just isn’t the same as for a traditional university course. We aren’t comparing apples to apples here.

This is not to say MOOC skepticism is unwarranted. There is a lot of edupreneurial bullshit and hype about MOOC’s. But that doesn’t mean it makes sense to fling equal and opposite bullshit, as that Harper’s statistic does.

Clay Shirky 03.29.14 at 3:55 pm

Just want to add a bit to John’s excellent answer #11 to @TM #6, especially this bit:

“There are reasons to force university students to take a whole course for credit. But that doesn’t mean that ‘did you take THE WHOLE COURSE?’ therefore becomes some sort of hallowed standard for seriousness, or an indicator of whether johnny is learning.”

For things like the ‘only 49% watch more than one lecture’ figure, you don’t even need to go as far afield as John does with the bail-out rate on shopping carts and more product information. Our own academic practice often includes both a ‘wish list’ of courses the student might like to enroll in (registation in a MOOC is nothing more than an item on a wish list) as well as a shopping period (which is analogous to watching the first lecture, to see how you like it. No one calculates their course enrollment as “The Number of Students Who Ever Sat In One One Lecture”, much less “The Number of Students Who Ever Thought About Taking My Course.”

The stock-keeping units we traffic in — course, credit, grade, department, major, and degree — aren’t traditions, they are just habits. There is nothing about them that shouldn’t be up for re-consideration, especially if it means generating a clearer idea of what it is we think the students should get out of our attempts to help them learn.

As a good CT reader would, I favor a capabilities approach to learning, which is to say that learning can be assessed on two dimensions — does the student leave class with capabilities they did not have when they entered, and do those capabilities turn into freedoms to do things in the world that benefit them, by their own lights. (As an aside, I read Paying for the Party on Harry’s recommendation, and was startled at how little the university in question cared about the answer to that second question, in advising those students about their university careers.

As John notes, many of the current attempts to answer that question in new ways suffer from undue early excitement. The thing that’s likely to be most worthwhile about the current wave of experimentation, though, is not that it is Teh Future. (2014-model MOOCs are no likelier to remain the norm by 2020 than Gopher remained the norm of info-finding in the 1990s.) The thing most likely to be worthwhile is that the Harper’s school of “Lets use the old units to measure the new models” is so obviously a bad fit for thinking about education that they are provoking a real conversation about how structured attempts to help other people learn should be designed and measured.

Main Street Muse 03.29.14 at 3:56 pm

John – “But that doesn’t mean that ‘did you take THE WHOLE COURSE?’ therefore becomes some sort of hallowed standard for seriousness, or an indicator of whether johnny is learning.”

How do MOOCs determine if Johnny and Jenny are learning? That’s what I wonder about these massive courses.

Who pays your salary as you do this? Your university? It’s free, right? So no skin in the game/no debt to accrue to learn this way. But how does Coursera make the $$ needed to invest in teachers, technology, etc.? Or is there the idea that once a course is developed, no further investment needs to be made?

There are stats about brick and mortar colleges that are alarming – among them being the stat that about 60% of those who enroll in four year colleges graduate – in six years. That’s a lot of $$ and a lot of time – and a lot of people who drop out with a huge debt load without ever getting a degree. http://1.usa.gov/1fybiRg

John Holbo 03.29.14 at 4:20 pm

“How do MOOCs determine if Johnny and Jenny are learning?”

That’s a tough one. So far I’m only objecting to the heavy hint that people must not be learning (because the drop-out and drop-off rates are so precipitous, compared to university courses.)

“Who pays your salary as you do this? Your university? It’s free, right? So no skin in the game/no debt to accrue to learn this way. But how does Coursera make the $$ needed to invest in teachers, technology, etc.? Or is there the idea that once a course is developed, no further investment needs to be made?”

Complicated. Yes, my university is paying me to do it, in effect. It’s free for the students. No debt and no real credit. Just ‘for fun’ – and a certificate at the end that is really just a gold star. Coursera makes money by licensing the platform to my university for internal use. There are also making money from some pay courses at the end of which a more serious credential is offered. The logic of course development is that you work hard to prepare once and then a lot is in the can next time. If the course doesn’t run at least a few times, after you record it, the production effort doesn’t make much sense. But that doesn’t mean the idea is that the course runs without an instructor, just without someone doing the lectures fresh each time.

The future is most uncertain.

Main Street Muse 03.29.14 at 4:39 pm

Thanks John. I appreciate the info about your experience.

“It’s free for the students. No debt and no real credit. Just ‘for fun’ – and a certificate at the end that is really just a gold star.”

Sounds better than the student athletes at UNC-CH who got “As” just for signing up for no-show courses… flagship public university that makes millions on its student athletes fails to deliver its side of the deal.

As I’ve said on other posts, I’m new to higher ed, after many years in the private sector – it has been an utterly fascinating experience. I’m doubtful that MOOCs can deliver what college students need, in that so many students seem to need the specter of an “F” to be fully motivated to engage with the materials (and that works not at all for some students!) But I also feel that the stat that only 60% of students graduate in six years is a huge failure on the part of brick and mortar institutions. And the skyrocketing costs have reached a tipping point. Something’s got to change.

John Holbo 03.29.14 at 4:42 pm

Hi Clay, thanks for the supportive comments.

Clay Shirky 03.30.14 at 1:17 am

Main Street #15, I think you’ve hit the biggest area of failure for MOOCs as constituted, which is motivation.

I’ve spent the last couple of years immersed in both the literature of complaint and renewal of higher education (Bok, Bowen, Gray, Christiansen, Menand, et al) and in the studies of the system as it exists today (Archibald and Feldman, Pascarella, Ginsburg, Tuchman, Armstrong, et al), and if I had to synthesize both into a sentence, I’d say this:

The core question in all forms of education is Who cares?, as in “who cares that the student learns?”

There are three possible answers: I care. We care. They care.

I care is personal motivation, usually expressed in its positive form: “I like to learn. I like the feeling of autonomy, and competence.”

We care is one form of social motivation, usually expressed as “My friends are also studious, and respect the effort it takes to learn.” (One finding from the Pascarella reviews is that being around studious peers creates a significant boost in learning.)

They care is another form of social motivation, usually expressed as “I want to impress the teacher/my parents/mentor/authority figure.”

In addition to the three usual ways of expressing these characteristics, each form has a negative version (though we don’t like to talk about this much in the US since the 1960s.) The negative versions of the three answers to Who cares? are “I don’t want to feel dumb”, “I don’t want my friends to look down on me”, and “I don’t want to disappoint my parents.”

And in addition to that, each form has an extrinsic version (though we don’t like to talk about extrinsic motivations in the US academy either, having inherited the British academics’ horror of working for a living.) The extrinsic forms of I care are “I would like a better job than I could get with just a high school diploma” or “I am afraid I will be suck in a dead-end job without a diploma.” The extrinsic version of We care is that same logic applied to the ability to support a family, and They care is about social or financial position.

So there are a dozen or so levers we can use to motivate students, but right now, MOOCs et alia mainly rely on just one of that dozen: personal, positive and intrinsic motivation. Reliance on this type of motivation assumes that learning can be made just so gosh darn awesome that people will do what they need to do with a song in their heart. This is a weird mix of Silicon Valley upbeat libertarianism and “Each child is a special flower who will grow in the right soil” educational theory. (The shadow version of relying on personal, positive and intrinsic motivation is that people who fail to learn on their own when given high-quality materials in a ‘go at your own pace’ format can be safely ignored, because they clearly failed to be members in good standing of the Church of Awesome.)

When MOOCs suck for student completion, they suck mainly in assuming that positive, personal motivation is enough. This certainly works for the one person in twenty for whom the love of learning is enough (these are people whose fit with learning is analogous to gym rats’ fit with exercise), but the other 95% of use need something other than ‘Woo hoo!’ to keep us focussed.

However, when traditional forms of higher education suck (which they do at a rate that we practitioners do not like to admit), they suck mainly in assuming that personal, positive and intrinsic motivation is irrelevant, and can be substituted with either fear of bad outcomes or respect for us, their wonderful teachers.

Like you, Main Street, I came into the academy sideways from industry, so I never internalized the sense that we professors are magic, or that the world owes us a living. We’re just workers, we have a job to do, we are visibly doing that job worse with each passing year, given the return on our students’ respective investments.

One of the reasons I am betting that experiments like the one Holbo is just finishing will transform the academy is that I am betting that new experiments in scalable education will be able to expand the number of relevant answers to the question “Who cares?” faster and more cheaply than traditional education will be able to trigger the intrinsic motivations of the students.

Anders Widebrant 03.30.14 at 1:48 am

To maybe do a little bit better than just saying that I liked the course, I will note that it compares favourably to when I read Plato in a physical school environment (first year political science). Not a fair comparison, necessarily, but John’s material reached much deeper into Plato’s philosophical framework than what I recall from my university class.

Clearly, one of the major advantages of the MOOCs is that they allow specialized and experienced teachers to reach a much larger audience. The lecturing component gets way better compared to schools that can’t afford, say, a serious dedicated philosophy department. And just as clearly, most of the opportunities for student engagement and discussion are lost to MOOCs, and it’s not clear that the MOOC vendors are really interested in addressing that problem.

Doesn’t it seem at least plausible that the standard MOOC template could include a set of best practices for organizing local study groups, perhaps led by people who have already taken the course once, plus perhaps an additional “TA guide”?

mdc 03.30.14 at 2:01 am

“though we don’t like to talk about extrinsic motivations in the US academy either, having inherited the British academics’ horror of working for a living.”

The only people I’ve ever heard talk about “extrinsic motivations” are the Department of Education, the President, every college president ever, the accreditation world, all guidance counselors, and the entire US media. Every time education is described as an “investment” (blech)- which is every time education is written about anywhere- the universal assumption that education is mercenary or instrumental is entrenched.

John Holbo 03.30.14 at 2:17 am

I know that I was personally so preoccupied just with getting the material produced that I didn’t do nearly enough on the motivation side. That is, I’m basically relying on people finding it interesting, counting on that being 1 in 20 people, and counting on there being enough people so 1 in 20 adds up. Next time around, when I’m not so fussed just to get the videos in the can, I’ll try to do a bit better.

John Holbo 03.30.14 at 2:20 am

Actually, I’m being too hard on myself there. I did one major thing, besides just canning videos. I showed up regularly with announcements and have participated in the forums. That’s not a lot, but it’s worth saying that the benefit of the teacher being a live person who who participates is motivational, as much as informationally instructive.

John Holbo 03.30.14 at 2:22 am

Clay is right that motivational issues are really the unsolved problem and about the best that can be said is that traditional university methods aren’t so great either, so if MOOC’s turn out to have a moderately crappy solution to the motivation problem, it’s worth remembering that all known solutions are moderately crappy.

Soren Kerk 03.30.14 at 4:30 am

You were great. The style was refreshing. The drawings are brilliant. I wish I had something intelligent to say, but I have only these compliments.

John Holbo 03.30.14 at 4:47 am

Thanks!

Maynard Handley 03.30.14 at 5:17 am

Two points.

On MOOCs: you have to ask yourself (as the “lecturer” for the course) what it is you are trying to achieve.

IF you are trying to replicate the college experience, MOOCs do that (to some extent, modulo interaction with other people, blah blah). BUT is replicating the college experience a sensible goal?

Speaking from my own experience, and that of my cadre of friends (university educated, in their thirties or forties) we are very interested in learning new things — but in a loose “get the big ideas” fashion, not in a detailed become an expert fashion. Rail against that all you like, but this is the reality of the human condition. I’ve reached 45 years old, I am a minor expert in my university discipline and my job discipline, AND I want to know something about history — all the history of all the world. And about biology — all the different facets of biology. And all the social sciences. And how petroleum is cracked. And what’s happening in nano tech. And paleontology. And … … …

The ONLY way to learn something about ALL these fields is to acquire what is admittedly a shallow quick knowledge.

But if that is the goal, MOOCs are now not an especially helpful system. They put way too much friction in between me and my goals. Something like iTunesU (especially iTunesU as it was five years ago, not the newer ever more MOOC’d version) is vastly preferable — I download the lectures as a podcast, I listen to them when I like on my schedule, when I’m rave enthusiastically to my friends, and we have interesting discussions on what new I’ve learned.

Basically this is the Teaching Company model of lectures.

It’s not my place to tell you how and where to put your lecturers. But I do think there is value in understanding (FULLY understanding) the audience for this material, so that you can decide exactly which part of that audience you feel it is you want to provide for.

Maynard Handley 03.30.14 at 5:30 am

As for my second point, I want to raise my personal bete noir every time I see utilitarianism mentioned.

“laws and public policies should aim, as a first approximation, to produce the greatest total good.”

Really? Is that EXACTLY the definition you want? Or should the definition be

“laws and public policies should aim, as a first approximation, to produce the greatest MEAN good.”

These are VERY different statements, with very different consequences.

Maximizing TOTAL good means you keep breeding humans until the planet is so overcrowded that each new human baby is GUARANTEED to have no more total happiness than total misery during its life.

Maximizing MEAN good means you stop as soon as the next human baby will have LESS happiness than the one born just before it.

One leads you to a planet of, I don’t know, maybe 300 million, humans all living like kings; the other leads you to a planet of 20 billion humans all living like animals. VERY different outcomes.

If people are not willing to be precise in what they are saying when careless words can imply either of two such different outcomes, this suggests that they are simply not worth listening to. They clearly have not thought through the FULL implications of what they profess to believe, which suggests that they’re either not too smart, or are using utilitarianism like “originalism” — as a way to justify whatever it is they already want to believe.

John Holbo 03.30.14 at 5:35 am

“These are VERY different statements, with very different consequences.

Maximizing TOTAL good means you keep breeding humans until the planet is so overcrowded that each new human baby is GUARANTEED to have no more total happiness than total misery during its life.”

I’m actually talking about that this week. Last week of the course. The moral of the story: Haidt’s rather belated turn to utilitarianism – though welcome! – is ultimately unclear.

Main Street Muse 03.30.14 at 11:59 am

Clay @ 17 “Like you, Main Street, I came into the academy sideways from industry, so I never internalized the sense that we professors are magic, or that the world owes us a living. We’re just workers, we have a job to do, we are visibly doing that job worse with each passing year, given the return on our students’ respective investments.”

Yes.

I am most troubled by how ill-prepared my students are for college (and even though I’m at a state school, I have enough out-of-state students to generalize that the lack of preparation is not just isolated to students from my state.

That’s why I think MOOCs will be great for older people needed a refresher or have curiosity about a particular topic, but not good at all for the 18-year-old who has not a clue about what this information is supposed to mean in the big scheme of things.

But again, floundering in the classroom and partying excessively while racking up enormous debt is a very poor way to start adulthood.

I am not familiar with the massive lecture course. My largest class has been one with 40 students. I cannot imagine assessing the performance of 1000s or 100s of students. I hate bubble tests with a particular passion.

Clay Shirky 03.30.14 at 12:42 pm

MDC @19, fair enough. I was trying to make a narrower point than the one I wrote.

What I should have said was that the members of my tribe (tenured professors at well-off colleges and universities) do not like to talk about extrinsic motivation, a point I think is reinforced not once but twice by your list. The first, minor point, is that none of the people you describe talking about extrinsic motivation are faculty.

The more serious underlining of my point comes in your own horror of even considering that education might be an investment. Yet what else could it be? If the expenditure of time, money and effort is not an investment, what is it? And if the outcome of the students’ investment of time, money and effort can’t be assessed in their increased capabilities, how can it be assessed? And if weighing present cost against expected future value isn’t amenable to instrumental calculations, why not?

Indeed, we don’t just invite students to make instrumental calculations, we require them to do so, from the moment they first have to decide which colleges to apply to, all the way through their assessment of the last elective they take in their final semester.

These measurements are complex, and as with all institutional goods, include incommensurable kinds of value. (“I learned how to solve differential equations” is hard to measure vs. “I discovered a lifelong love of the visual arts” vs. “I met my closest friends there.”) But the people we are paid to help are making decisions based on the effect they hope we will have on their lives.

We (me and my tenured tribe) don’t like to talk about this, because it hurts our feelings. (Like many institutions whose organizational model predates democracy, we never really got over the conviction that we are secretly priests.) But does it not strike you as curious that college presidents, included on your list of the feckless and faithless, are drawn from the ranks of faculty? What do you think happens to them, these former faculty members, that they fairly uniformly abandon the idea that our institutions should provide no value that could be called instrumental?

Main Street Muse 03.30.14 at 1:36 pm

To MDC – what is the point of spending all that money on a college education, if it is not an investment?

Even at “cheap” state schools, it’s about an $80,000 investment of funds to get a degree – in four years, which, apparently, is out of realm of possibility for many students. (60% of those who enroll at a four-year institution graduate in six years – and less than 40% graduate in four years.)

mdc 03.30.14 at 4:19 pm

“what is the point of spending all that money on a college education, if it is not an investment?”

” If the expenditure of time, money and effort is not an investment, what is it? ”

At its best, a deeply valuable consumable, a high pleasure, a constituent of human flourishing. What if one’s studies afford insight into important truths? This would be intrinsically worthwhile. I’ll concede that many students don’t get this kind of experience. But I think were a wealthy enough society that we should be able to offer it to those who want it.

bianca steele 03.30.14 at 5:29 pm

Here are two possible analogies to a college education:

1. The piano lesson model. Only some kids take piano lessons. They’re one on one and require significant money and effort over a long period of time. Some people advance quickly and some don’t. Anyone can quit at any time if they are happy with how much they’ve learned or can’t afford the money and time anymore. Most people who take lessons do so for their own enjoyment. Classwork can be reproduced at home, or anywhere, and can be observed by parents and friends at any time.

2. The gymnastics class model. There are lots of gymnastics classes, and for little kids, these are advertised as teaching important skills, values, and abilities for every kid, unrelated to advanced gymnastics competition–there’s no other place to engage in those activities outside of gymnastics classes, either, especially for small kids. Classes are relatively large and parents can’t really see what’s going on, observe work outside class, or help their kids learn. But general gymnastics classes are generally also attached to advanced classes that are restricted to the most talented, and to very competitive teams. The little-kid classes accept unusually talented kids, as well as the average and below-average. But there isn’t time to teach them, and in the worst cases, they’re just ignored and subtly told they’re not good (in traditional gym-teacher fashion), so they’ll decide to stop attending. So only the very best end up learning those skills, and this suits the gyms fairly well, because what they’re really interested in is high-level performance.

It seems that in many ways and for many people, college is more like the latter experience. Education, like gymnastics performance, is viewed as an intrinsic good. Its collateral benefits are played up because there’s community interest in them. But it doesn’t work for many people, and they’re often embarrassed both to admit that they failed in that setting, and that they haven’t found a way to turn the failure into a learning experience for themselves but are still “blaming others.” I’m not sure MOOCs are the answer, but I think my analogy is more specific than Clay Shirky’s “priests” or the dichotomy “high pleasure”/”investment.”

bianca steele 03.30.14 at 5:46 pm

I suppose there’s also:

3. The soccer model. For little kids, you show them some skills implicitly, and then let them run around and play (the balance between these depending on the program). Some will take the opportunity to get better, slowly or quickly, and some won’t really. At some point, they get sorted into talented and less talented (although for a while there are still plenty of opportunities for the less talented to keep participating), and this is pretty much going to happen according to skill- and interest-level, but it’s the kids themselves who do the sorting.

The soccer model seems like an ideal-type of how education tends to actually happen when there’s a general belief that no one’s really going to be told they’ll never kick a soccer ball around again, and there’s little desire for an ultra-elitist piano-lesson model.

bianca steele 03.30.14 at 5:46 pm

implicitly -> explicitly

Harold 03.30.14 at 6:54 pm

I think there is a lot of sense in education as a societal investment because our system needs a lot of redundancy in order not to have to keep re-inventing the wheel with every generation (about 20-30 years?). There may not be so much sense in higher education as an individual investment.

As far as music instruction, Kodaly’s method was developed to work in group lessons, though he devised it as a preparation for supplementary individual piano, or other instrument lessons to be taken later. It is a cumulative method, based on folk music, that begins in nursery school with hand gestures taught to accompany very simplest musical intervals, gradually becoming more complex as the grades advance and adding harmony and rhythm. This is a video of Hungarian primary school children sight-singing a choral piece by Mendelssohnn that they have never seen before. http://youtu.be/PdaY2E3BL1M

I understand that to learn solfège, it really needs to be done on a daily basis, preferably in a classroom, over a period of years. There is a lot to be said for group lessons, IMO, because they are much more fun. There are several videos about the Kodaly method on the web.

Clay Shirky 03.30.14 at 9:50 pm

Working backwards.

Harold @35, I’ll contend that exactly the opposite thing has happened. Education used to be a social good, back when the basic bargain of US society was that the college educated created or managed the jobs that would be done by the high school educated, and those jobs would pay well and last for life.

Since 1975, however, US productivity gains have continued, but the link between productivity and wages was decisively severed. (http://thecurrentmoment.files.wordpress.com/2011/08/productivity-and-real-wages.jpg)

Since the mid-1970s, holders of Associates Degrees and higher have well outperformed high school degree holders in almost every measurable category of income or well-being. Higher education is now mainly a private good, whose value is principally captured by the degree holder.

@Bianca #33, your soccer model maps really nicely to the Paying for the Party thread a week or so ago. (https://crookedtimber.org/2014/03/23/paying-for-the-party/) Like your naively self-sorting soccer players, the women studied were allowed to make disastrous choices about their college careers, including switching to less stressful majors in order to join the dominant party culture of their university, without anyone telling them that they were sacrificing the very instruction that would enable them to do the things they wanted to do after college.

Indeed, one of the most consistent themes of PftP is how little the employees of that university, nominally advising these women, were interested in offering any useful advice at all. In this vacuum, the biggest predictor of success seemed to be having parents who understood what was required of college students and who could help sort good from bad choices from afar.

@MDC #31, there are so many reasons to reject that model, starting with the fact that it is not true. A vast majority of freshman understand themselves to be going to college to learn things that will aid them in the world of work, and the willingness of both their parents and the state to either incur or subsidize significant debt is directly tied to the pursuit of that goal. (http://chronicle.com/article/Freshman-Survey-This-Year/136787/)

The next reason to reject your model is that we, the faculty, know that it is not true. College in the US has always had an explicitly vocational component, starting with the training of ministers in the 1600s, and the period immediately after WWII transformed that into the dominant theme of both our organizational forms and our funding.

The states did not suddenly increase our subsidies in the 1960s because the good people of Ohio and Alabama and Montana wanted to see “human flourishing.” They jacked up our funds because the Russkies had a bird in the sky and we did not, and for 15 years, we treated education like a Cold War imperative, and funded it at military rather than civilian levels.

For the last two generations, our revenue has been fairly explicitly tied to us producing an effective ticket to a stable, middle-class job. For us to pretend that this is not the source of our income would be like the good folk at Ceasar’s Palace insisting that US citizens flocked to the casino floor wanting an encounter with the ineffable pleasures of stochastic processes, and that any hint that people might be looking for a payout was pure slander.

But the most important reason to reject it is that it doesn’t make any sense even on it’s own terms. If you want to talk about “human flourishing”, that’s pretty obviously going to include people’s jobs, given that that is what they will do with a big chunk of their waking hours, and will present the environment in which they face significant challenges of both skill and character, and that remuneration from said jobs will have an effect on their ability to support a family, as well as supporting, say, an appreciation of various forms of art, or travel.

The only possible case in which human flourishing wouldn’t include such a central fact about people’s lives would be if the people in question were wealthy enough not to need a job, or if the mere fact of being ‘college educated’ was enough to secure them a job with little regard for the particularities of school, major, or performance. That first condition corresponds to the state of US higher education prior to 1940 (when the high-water mark for college attendance was 5%, virtually all well-off white men), while the second corresponds to the state of the US economy during its managerial and sub/urbanizing phase, from WWII to the mid-1970s. Neither case exists today, nor has for 40 years.

Your sense that most students do not get the pure ethereal experience you valorize is correct, but the cause is not some moral failing of either the students or the institutions. It is because most students expect higher education to do a different job than this, and most institutions of higher education are set up for that job.

There are a handful of English and History departments, at a single-digit fraction of institutions of higher education, that have the luxury of continuing to produce a credential of such basic value (a degree from Stanford, say, or Johns Hopkins) that they can comport themselves as if their students are independently wealthy, and thus can regard anything as demeaning as employment as being beneath discussion inside the classroom, but this is such a minority of faculty at such a minority of institutions that they are completely unrepresentative of any truth more significant than “When you have a lot of money, you are free to do as you like.”

@Main Street #28, I know I’m all “Blah blah blah Paying for the Party blah blah” in this thread, but when you say “…floundering in the classroom and partying excessively while racking up enormous debt is a very poor way to start adulthood,” one of the eye-opening things for me about that book was the ways in which what Armstrong and Hamilton call the Party Pathway is a great way to start adulthood if you are a) well-off and b) connected and c) outgoing.

The university in question (Indiana, I think) goes out of their way to make the party pathway work for those students, even as it creates an attractive nuisance for students not suited for it. (The merely middle-class students who thought that joining the party pathway would allow them to achieve the same outcomes as the socialites all come to grief.) That pathway also creates negative externalities for students not interested in partying but being on a campus dominated by it. (Armstrong and Hamilton’s most surprising discovery was that several women who quit the flagship campus and went to poorer regional campuses, and did better, by being away from the distractions.)

mdc 03.31.14 at 2:01 am

“it doesn’t make any sense even on it’s own terms”

Huh? Because if it’s not mercenary, it’s not worth doing? Sounds incoherent to me. We make money in order to live, right? We don’t live in order to make money.

I like Bianca’s analogies. Here’s another: one thing that has contributed much to my happiness is the National Park system. It hasn’t put food on the table or paid the bills, it has simply allowed me and my family to spend time in beautiful nature. I’ve counted that as intrinsically good. In the absence of our park system, it would be easy to say that the only people who can afford to lounge about in the choicest parcels of nature are the (decadent) wealthy, so we shouldn’t care about those sorts of goods. But in fact, thanks to the parks, many working class families like my own were able to enjoy views previously available only to the Rockefellers.

The pleasures of education rank higher, I think, than the pleasures of natural beauty. But they both are forms of leisure. You’re right that most colleges aren’t set up for the job of serious leisure (which, in this case, has nothing to do with partying). I don’t vouch for whatever racket they’re running.

Main Street Muse 03.31.14 at 2:05 am

Clay Shirky @36 “The university in question (Indiana, I think) goes out of their way to make the party pathway work for those students, even as it creates an attractive nuisance for students not suited for it. (The merely middle-class students who thought that joining the party pathway would allow them to achieve the same outcomes as the socialites all come to grief.)”

I am getting this book this week to read it. However, it was my understanding from the synopsis that the education was less relevant than the background – that the parents were the relevant piece in the success of the students, not the college educational experience. Is that not true? The party pathway actually helps well-connected students with careers, not the parental connections?

John Holbo 03.31.14 at 2:38 am

“Huh? Because if it’s not mercenary, it’s not worth doing? Sounds incoherent to me.”

mdc, surely you recognize that Clay is not saying that if it isn’t mercenary, it isn’t worth doing.

in effect, you are proposing that higher education should be a public leisure good, like a national park that is free to all. But you also recognize, surely, that most (or at least some) students go to college to get jobs after they get out of college. (When Clay points this out you feign shock that he could be so ignorant of the ideal of liberal arts education. But obviously he’s not. He’s drawing attention to the realities of liberal arts education.) If you have an idea for turning higher education into a free, public leisure good – well, we’d all love to see the plans.

“I don’t vouch for whatever racket they’re running.”

If you aren’t vouching for their racket, then what is your point?

Don’t say you are pointing out that, if you had a magic wand, you would choose to make education more perfect than anything anyone is proposing could ever achieve. Because I rather imagine that Clay would use the magic wand, too, if he had one. (Why wouldn’t he?)

Harold 03.31.14 at 2:52 am

It is not a good private investment for graduates with hundreds of thousands of $$ debt and no job prospects. Up until the 1970s there was a labor shortage. Now college seems to be a way to keep people out of the labor market. Jobs that used to require a college degree (and formerly just a high school degree, which used to mean something) now require additional graduate degrees in business as well. But it is still arguably good for the society to have an educated populace (up to a point), and it would be a social good if people could have access to adult ed throughout their lives.

It is not good to have an unemployed and debt burdened populace.

flashback: http://www.economist.com/blogs/banyan/2011/11/education-south-korea

John Holbo 03.31.14 at 4:10 am

Not to yet further break the butterfly of mdc’s objections on the wheel of what Clay was actually saying, but it’s worth noting that the ideal of liberal arts education as spiritual good in itself is a kind of four-year program of assisted auto-didacticism. One problem with holding up this ideal, to reproach MOOC’s, is that MOOC’s are actually good at assisted auto-didacticism, for those capable of it. (If there’s a problem, it is that MOOC’s are only good for this, not that they are not good at this.) If you are the sort of student who could get the spiritual benefit of going to Harvard, and taking philosophy, you are probably the sort of student who would benefit from a philosophy MOOC. I’m not saying Harvard isn’t better. But the MOOC is a lot cheaper and less rivalrous, as goods go.

Main Street Muse 03.31.14 at 9:39 am

John @41 – I don’t think people go to Harvard for the spiritual benefits.

John Holbo 03.31.14 at 9:45 am

“I don’t think people go to Harvard for the spiritual benefits.”

It’s a fair cop, guv.

mdc 03.31.14 at 12:50 pm

” I don’t think people go to Harvard for the spiritual benefits.” Not in general. Not sure I would recommend Harvard for someone interested in such “ethereal” goods.

John @41, I wasn’t objecting to MOOCs, only to the claim that the problem in higher education is faculty’s belief in the intrinsic good of education. I wasn’t vouching for the status quo either, but critiquing it from the other direction.

But if we all agree that education is not only an “investment,” and that learning is good in itself, then the rest is just tactics. Maybe MOOCs could even be part of the “magic wand”!

bianca steele 03.31.14 at 1:26 pm

Clay Shirky @ 36 (The merely middle-class students who thought that joining the party pathway would allow them to achieve the same outcomes as the socialites all come to grief.)

However, this is the plot of The Great Gatsby, and in fact of all Fitzgerald’s life, which seems to suggest that it isn’t new and isn’t outcome-driven.

Random Lurker 03.31.14 at 2:48 pm

A modest proposal from a non academic to create a model of education where people do not get in for mercenary interest, but for interest in higer goods.

1) Provide full employment for everyone, regardless of educational results.

2) Reduce the workweek to 20h. This might help to reach step (1). If someone tries to work for more than 20h/week, send him to the gulag as a would-be kulack.

3) Divide education between “liberal” and “vocational”.

4) When people take up vocational education, they are paid for it by the government. This count towards the limit of 20h of work they are allowed to do. The government pays a living wage for this, and this substitutes all form of govenment help for the unemployed. People CAN live all their life on this if they want (but since the wage is low, once they have the skills they are likely to go in some other job).

5) When people take up liberal education, this is somewhat subsidized but counts as leisure, and it doesn’t count as “work”. If it happens that people with some liberal education knowledge get on average higer wages than the rest of the population, those courses are changed in “vocational”.

Vote for me in the next presidential elections, and I promise this will become reality. Random Lurker for president!

PS: While on some level I agree with mdc’s ideal, it seems to me that this idea of the “free intellectual” was born in a period when very few people could actually have a good education, so that liberal education was a class marker, and in some way legitimized the class structure (as people in the ruling class looked on average more “spiritual” than their lessers).

There is clearly a similarity to piano lessons, so that daughters of the lower middle classes could look fine and get a good husband (even if “music” in itself can be seen as a consumption good).

So this is something quite difficult to obtain in a more democratic world, where a “free” education can’t grant you a good job, and of course if you get that education you aren’t already on the job market or are missing more profitable career paths.

On the other hand, the degree only makes sense as an investment as a positional good, so that the idea that if you academics only worked better all your students would get nice jobs is also impossible.

TM 03.31.14 at 2:58 pm

Thanks for the response John. I’m all in favor of putting learning materials out there for free (I actually do that myself, wink wink) but obviously I am suspicious of the MOOC/e-learning hype. The fundamental problem with present-day education debate is that while the status quo is highly problematic, the “reform” direction pushed by the corporate and political mainstream (which are all touting the panacea of e-learning) is fairly certain to make things worse. What is lacking is a visible progressive reform agenda.

Clay Shirky 03.31.14 at 3:42 pm

About MDC’s contention that the ideal college experience is a leisure good, #37 et passim, Holbo posts for me.

About Paying for the Party and the party pathway:

@Bianca#45, that’s right, it’s an old story. But it’s not a consistent story either. It was true in Fitzgerald’s time, and it’s true today, but it was not nearly as true in the three decades after the second world war.

That was an era in which much new money was made, and, towards the end of that period, old money lost the ability for their policing of the boundaries of membership to mean as much. (Have you, by the way, read George Trow’s In the Context of No Context? It’s an odd little book, but one of the great themes is how the one-two punch of the 60s and 70s spelled the end of the US mainstream, East Coast/Mainline Protestant division.) What Armstrong and Hamilton point out about the sort of replication of privilege is not “T’was ever thus” but rather “It’s baaaack.”

At Indiana, neither the students nor parents were conditioned to assume (or even, frankly, consider) the idea that certain forms of training for future work would be off-limits because of class (seemingly because that was the way the US worked when the parents were young.)

And IU, who actively supports the Party Pathway, also provides no mechanism for telling, say, a working class student that she should not study to be a wedding planner unless she visibly fits into the class to which the bride aspires, or that some kids can get away with partying because ordinary consequences for their actions to not apply to them.

There has always been an aspect of this in US life, of course, but I think the Fitzgerald parallel is interesting precisely because class reproduction was reduced in living memory, and college had previously been one of the mechanisms of such reduction.

As an aside, one theme that Armstrong and Hamilton take for granted, but jumped out at me, was the ways that delayed engagements reduce the ability for women to ‘marry up’. Because college, even now, compresses class distinctions and assortative living arrangements somewhat, working and lower-middle-class women have more access to college-educated men during college than they will after (because the neighborhoods where degree holders cluster will tend to be too expensive.)

So there used to be a certain ‘double-blind’ logic to college engagements — the women had a hard time assessing the men’s likely employment trajectories, and the men couldn’t as easily select women from a narrow class pool.

Not saying we should go back to getting engaged at 21, just that the delaying of the age of engagement is one of the drivers of assortative mating, which hadn’t occurred to me before.

@Main Street #38, the book makes clear that the educational experience is not entirely irrelevant, on two grounds. First, the women in question do major in things like tourism and broadcasting, so there is some familiarity about the content, and job requirements and categories, in those fields. Then, two, the educational component of college is not confined to the classroom, and for many of these women, the parties were training for a particular sort of career.

Where I went to school, working on the school newspaper and putting on plays and musicals were both well-oiled means of getting jobs in publishing and theater after graduation, even though neither activity was supported by the curriculum. Holding your liquor, keeping up your end of the conversation, and remaining upbeat while dealing with drunk frat boys all turn out to be life skills needed for a variety of careers in media and tourism.

Harold 03.31.14 at 3:54 pm

I have heard (can’t verify) that the ability to play the piano used to be a requirement for being an elementary school teacher. My grandmother went back to work just before the depression so they could buy a piano and her daughters could have piano lessons, something my grandfather didn’t think necessary. It was a good thing, too, because my grandfather lost everything in the crash and my grandmother’s teaching job saved the family from being thrown out on the street. Her job meant they were even able to help other relatives who weren’t so lucky.

bianca steele 03.31.14 at 6:15 pm

Clay Shirky @ 48

Haven’t read Context of No Context, though I’ve read snippets, and I’ve read “E Unibus Pluram,” so I feel like I’ve read it. But wasn’t the thread running all through Trow’s book the Problem of Feminism (didn’t get that from DFW, I’m sure, but I don’t remember where I did)? And most of those books tend to be The Golden Age Is Over (except for me, because I’m super-fantastic, but definitely for you), or The Golden Age Is Over (and that’s pretty much why I admittedly suck, just like you). I didn’t realize for Trow the golden age was the welfare-state consensus era, however.

I’m waiting for my copy of the book, but I’m surprised by some of the details I’ve heard so far. Thirty years ago, communications was considered obviously a direct-to-job major, and there are still lots of people in marketing, communications, and related fields who are making decent money but aren’t upper-class in the way suggested by these discussions. The only communications major I know who didn’t get a job had AFAICT intentions of “going into radio” and might even have been better off in English or sociology. Schools of Communications aren’t exactly bastions of ivory-tower intellectuals.

LFC 03.31.14 at 6:52 pm

Haven’t read every word in the thread, but re the “spiritual benefits” stuff:

The notion that there is one kind of U.S. university, Type X, where one goes to make connections, become a member of the power elite etc etc, and another, Type Y, where one goes if one is mainly interested in getting a good liberal education, is really bullshit. It’s too clear a demarcation for what exists in reality. And by extension the picking out of a third type, Type Z, as a ‘party school’ is also prob. a bit overdone.

Not to say there aren’t significant differences betw institutions, of course, but they don’t fall neatly into these stereotypical, stupid categories, imho.

LFC 03.31.14 at 6:58 pm

clarification: ‘liberal’ in the sense of ‘liberal arts’

Clay Shirky 03.31.14 at 7:51 pm

@Bianca #50:

The Trow is too weird to fit any one narrative (including mine, of course), so yes, The Problem of Feminism is in there, as is, sub-rosa, The Problem of Jews, both of which forces helped weaken the Anglo Old-Boy network Trow’s family rests in.

The oddest part of the book (well, an oddest part) is that it is elegiac for the East Coast publishing mainstream without the author’s actually having liked that mainstream very much, which brings in the even more sub rosa issue, The Problem of The Gays (the one problematic class of which Trow was a member.) There’s an odd reminiscence of New York after the 60s broke everything, nights at Studio 54 with a kind of fun-house version of Lady Astor’s list, all of which the author participated in.

Yet by the 1980s, he seems disoriented by the fact that his own participation in that scene helped weaken the mainstream. Like a gentrifier who is mystified that gentrification didn’t stop when he moved to the neighborhood, the book reads to me like Trow’s grappling with the idea that Studio 54 (and The Factory and Max’s Kansas City etc etc) weren’t actually counter-culture anymore, they were the culture of New York City (the center of his world), and that the bacchanal that took place in the 1970s wasn’t oppositional so much as corrosive, and that he was part of the corrosion.

The book is one of these rare instances where, when the author says “The Golden Age is Over”, he really means it as a flat description of what happened, rather than as a jeremiad, and he even includes himself in that change.

But the real reason to read it is that it weirdly hypnotic, if you are in the right mood. For months after I read it, I wanted to write like that, until I realized that (as with, say, Bill Burroughs and Naked Lunch) the writing style was suited to exactly one book, and couldn’t be easily re-used, even by Trow himself.

As for IU, those girls mostly weren’t upper class, not in the way you’d describe such a thing in NYC or SF or LA. Their parents were doctors and lawyers and, in the most notable case, a CFO. They were not venture capitalists, hedge fund partners, or CEO’s of multi-nationals or post-IPO internet firms. So the language gets a bit confusing, because she’s talking about children of the 10%, not the 1%. They were still getting drunk in parking lots in the Midwest, not in private houses in Aspen.

Shatterface 03.31.14 at 9:04 pm

In The Righteous Mind, Haidt spends a great deal of time abusing utilitarianism as a symptom of intellectual error – even of personal autism.

Pointing out that Bentham, based on the reports of his contemporaries, quite likely had Aspergers is not abuse.

novakant 04.01.14 at 1:25 pm

If you have an idea for turning higher education into a free, public leisure good – well, we’d all love to see the plans.

I don’t know about leisure but tertiary education is free (or almost free) in many countries – and it should be. I find the idea of spending $80.000

novakant 04.01.14 at 1:27 pm

ctd.:

I find the idea of spending $80.000 or whatever and being saddled with student loans perverse. Education should be funded by the state.

AcademicLurker 04.01.14 at 2:04 pm

I don’t know about leisure but tertiary education is free (or almost free) in many countries

This. Much of the discussion of Higher Ed. by self-styled reformers, especially those of the “we must destroy the village in order to save it!” persuasion, reminds me of discussions of health care. It pointedly ignores the fact that other societies seem to have figured out a way to manage it in a way that is, while not perfect, at least reasonably functional.

It’s not inevitable that post-secondary education leaves people with crippling debt loads. It happened that way in the U.S. for a reason.

AcademicLurker 04.01.14 at 2:05 pm

“a way to manage it in a way”

Department of redundancy department. Maybe I should sign up for a MOOC teaching composition.

Chatham 04.01.14 at 2:46 pm

The simplest and easiest solution would be to expand the free public education system another 4 years. I ran some rough numbers and it looks like it could be done fairly cheaply. 3 states (Oregon, Tennessee, and Mississippi) are currently working on making community colleges free; both California and NYC had free colleges in the past.

bianca steele 04.01.14 at 2:56 pm

Just saw this from Random Lurker @ 46: There is clearly a similarity to piano lessons, so that daughters of the lower middle classes could look fine and get a good husband (even if “music†in itself can be seen as a consumption good).

If so, this would be an example of an activity that once was expected of the daughters of the upper middle class, is now considered an activity only of the most strenuously striving members of the lower middle class, and just happens to be suited to introverts and the non-athletic–similar to the way education is perceived (vocational or otherwise) in some of the places similar to the university described in the book.

This could be different in different places, of course.

mdc 04.01.14 at 3:45 pm

Bianca:

Not sure about the “introvert” part. Anyway, the analogous case against leisure would be that since music lessons can’t get you a husband anymore, we should abandon music instruction for those who can’t already pay for it. Because what else could it be good for, if it’s not an investment?

Clay Shirky 04.01.14 at 3:59 pm

@AcademicLurker #57, it did indeed happen that way for a reason, and the reason is that half a century ago we American academics accepted a degree of Cold War funding that committed us to a mode of organization we could not support but would not dismantle when that funding ended.

Fun fact, via Louis Menand: More faculty were hired in the 1960s than in the entire period from 1636 to 1959, a boom accompanied by a totally uncharacteristic boost in state funding, largely driven by fears of an “education gap” with the Soviet Union. When that funding reverted back towards the mean, it was still far higher than it had been in the 1950s, but because it was lower than its peak, we academics have felt aggrieved ever since.

The fact that, averaged across 50 states and 20 electoral cycles, the consensus answer to the question “Can we have a lot more money?†has been No is always regarded, in the academy, as a temporary injustice. Our strategy has been to assure ourselves that once taxpayers and legislators understand that a failure to vastly increase our subsidies would force us to change the way we do business (which no thinking person could possibly expect us to do) they will reverse 40 years of practice and write us a blank check for 7% annual increases in income into the distant future.

Meanwhile, since we’ve actually had to continue working during those 40 years, we have become majority-contingent institutions. The positions of the AAUP, AFT , et al have been completely incoherent on the subject of contingent labor, because the one obvious solution — share the benefits of college employment more equitably — is anathema to their core commitment, which is that me and my tenured peers should not suffer at all, no matter what happens in the broader hiring landscape or economy.

And because we and our unions committed ourselves to preservation of the structure of the go-go years for us we have been willing to accept a dualized labor market, where tenure is kept for all past holders, but almost completely withdrawn for present and future hires. (Something like 9 out of 10 teaching positions on offer in any give year are not on the tenure track; it has been removed as a primary characteristic of academic hiring, and remains only as a tool for recruiting star faculty to relatively well-off institutions.)

So, as you might expect, I regard all forms of Norway-porn as being descriptive or predictive of little that is possible in the US, but as you might not expect, I do not believe that this is because of some inherent weakness in our political system. The principal obstacle to moving towards a more Continental model of education is we ourselves.

To move to a Continental system of higher education would make faculty fairly uniformly employees of the state, and would make teaching, not research, the central preoccupation of both the legislators and the administration. Senior faculty would have to take pay cuts of around a quarter of our current salaries, and see our teaching load go up by about that same amount, to make the economics work out.

The look of destroying the village in order to save it really depends on what you think of as ‘the village.’ If, like me, you think that we take our money in order to educate our students, and that the research prestige-ladder has led to gross (and soon unsupportable) economics for institutions of middling quality, than destruction looks like a pretty good strategy for re-aligning our resources and goals.

If, however, you regard the high average salaries and historically and globally remarkable low teaching loads in the US as the thing that needs protecting, moving to a Continental system will destroy what you are trying to preserve more completely and more swiftly than a victory of, say, the recently accredited University of the People will.

Clay Shirky 04.01.14 at 4:22 pm

@mdc #61, I think you’re using the word ‘investment’ in a funny way. Learning to play the piano is always an investment, as in “to use, give, or devote (time, talent, etc.), as for a purpose or to achieve something.”

It’s mostly not an investment with a monetary payoff, but that doesn’t stop it’s being an investment, and it doesn’t stop the calculation of the student and their parents being “Will present investment of time and energy be worth the future increase in capabilities?”

To take one of the famous arguments about higher ed, when Harvard stopped forcing its students to study Greek, the president of Princeton wrote a fairly epic rant complaining about the change, but what charles Eliot had understood was that knowing a bit of Greek was simply less valuable, as an acquired capability, than it used to be, and that this decrease was significant enough to be worth clawing back the time and energy previously devoted to it.

You seem to want every calculation of present effort against future value to be about money, but many such calculations are not, including learning to play the piano. The fact that those calculations are not mercenary does not make them any less about investment and payoff.

There is no abstract sense in which it is “good” to play the piano (or speak Greek or be able to solve differential equations.) Those capabilities are good only inasmuch as they increase your freedom to do things you need or want to do in your life.

So of course if playing the piano now has a less useful effect on, say, finding a mate, that means that, without some compensating improvement elsewhere, that playing the piano has become less valuable.

AcademicLurker 04.01.14 at 5:00 pm

@Clay Shirky#62:

A quick look around brings up this example data, showing that UC system fees remained remarkably flat from 1970-1990. If the bubble burst around ’70, as conventional wisdom seems to hold, what was going on during those 20 years. Did the nature of higher education in CA undergo some sort of radical change ~2002, requiring fees to skyrocket?

bianca steele 04.01.14 at 5:16 pm

mdc:

I don’t understand your “introvert” comment, and I think you’re arguing with Random Lurker, who I quoted, not with me.

Harold 04.01.14 at 5:49 pm

I’m on board with Clay Shirky except for the reference to “we and our unions” — I don’t know if the academic guild can be called a union.

LFC 04.01.14 at 5:59 pm

Clay Shirky @63

There is no abstract sense in which it is “good†to play the piano (or speak Greek or be able to solve differential equations.) Those capabilities are good only inasmuch as they increase your freedom to do things you need or want to do in your life.

There is a tension between this statement and one of the stated or implicit justifications for distribution requirements (or ‘general education’ etc), namely that it’s good, in an ‘abstract’ sense, to have some acquaintance with a range of subjects or to be minimally culturally and/or scientifically literate (whether such requirements succeed in accomplishing that goal is a separate question, to which the answer, I suppose, very often might be no). While I’m sure it’s possible to justify such requirements in terms of valuable (for whatever reason) ‘capabilities,’ my impression is that that is only one of the ways in which U.S. universities justify them now.

Btw, the other day I was walking on a street and saw an ad on the side of a busstop for a local (i.e., in the general region) university which was all about how the analytical skills imparted by this place were valued by employers. So I recognize that the ‘abstract’ justifications for higher ed., to the extent they still exist, are prob. fading away or eroding under the pressure of various, obvious forces. But the abstract justifications aren’t quite extinct yet, istm.

Harold 04.01.14 at 6:47 pm

Piano, if the sages ask thee why …

mdc 04.01.14 at 6:55 pm

“Those capabilities are good only inasmuch as they increase your freedom to do things you need or want to do in your life.”

I don’t think any capability can be good unless exercising it is good. Some activities are good in themselves, and for some of these, you acquire capability on them by doing them. But the point of learning to play the piano is not ‘to be good at playing the piano’, it is to play piano well.

You really seem to be presupposing that no activity is intrinsically valuable.

And Bianca, I didn’t think I was arguing w you at all.

Harold 04.01.14 at 7:08 pm

“My piano is to me what a frigate is to a seaman, his horse is to an Arabian, and much more! Up to now it has been my essence, my language, my life! ..” Franz Liszt, “Travel Letters”, 1837.

***

The following, if not true, is a good story:

“The following story about Albert Einstein was told to Charlie Chaplin by Mrs. Einstein: ‘The Doctor came down in his dressing-gown as usual for breakfast but he hardly touched a thing. I thought something was wrong, so I asked what was troubling him. ‘Darling’, he said, ‘I have a wonderful idea.’ And after drinking his coffee, he went to the piano and started playing. Now and again he would stop, making a few notes then repeat: ‘I’ve got a wonderful idea, a marvelous idea!’

I said: ‘Then for goodness’ sake tell me what it is, don’t keep me in suspense.’ He said: ‘It’s difficult, I still have to work it out.'” She told me he continued playing the piano and making notes for about half an hour, then went upstairs to his study, telling her that he did not wish to be disturbed, and remained there for two weeks. …. Eventually he came down from his study looking very pale. ‘That’s it’, he told me, wearily putting two sheets of paper on the table. And that was his theory of relativity.’ ” from My Autobiography, by Charles Chaplin.

Clay Shirky 04.01.14 at 10:55 pm

@Academic Lurker #64,

Archibald and Feldman have the most complete accounting for the cost dynamics of higher education I know of, in Why Does College Cost So Much (http://www.amazon.com/Why-Does-College-Cost-Much/dp/0199744505, and capsule summary: http://www.insidehighered.com/views/2010/10/19/feldman)

They follow the rising cost (not price) of higher education, and they note that colleges, like any institution that used skilled labor as a non-tradeable input and measures its output in terms of time invested (e.g. the credit-hour), will suffer from Baumol’s cost disease. It costs more to go to Ball State this year than last, and will cost more again next year than this, for the same reason those dynamics apply to seeing a Twins game or attending the Santa Fe opera.

So A+F says three different things about UC price (not cost) over the decades you show. The first is that in 1975, the year in which state subsidy peaked and began falling rapidly (http://goo.gl/9tetW), inflation had dealt such a blow to tradeable-sector productivity that college costs remained flat, and didn’t begin rising until 1979. So for the earliest part of the chart you, point to, price was relatively flat because cost was flat.

Then, from 1982-1990 or so, college prices stayed relatively flat because, after a sharp increase in price during the recession of the early 1980s, colleges subsidized the price with other adaptations, principally increasing contingent labor and student:teacher ratio. These adaptations kept cost disease temporarily at bay by changing the underlying product to be less reliant on tenured faculty in small classes.

(When the US News college list, which is highly dependent on S:T ratio, launched, there were two UC universities in the top 10 — Berkeley and UCLA. Now there are no UC — or even public — schools in the top 25. This is emphatically not to say that US News measures educational quality, just that, given the things it does measure, the total evacuation of public institutions from the top of its list gives you an idea of the cost-saving dynamics at work.)

And then Phase III, starting in 1990s, where, as you note, the price dam burst. What happened to public schools, whose price rise has been later but more dramatic than private schools, is that state legislatures, even California’s, gave up on the idea that it could continually subsidize costs out of either tax base or increasing class sizes, so they allowed price to began converging towards cost.

Against the thought that this is mere politics and could easily be reversed, it’s worth noting that cost (not price) is increasing throughout 4 year colleges at a compound rate of a bit over 7%, which means it is doubling about every 10 years. Even if California were to commit to reset tuition and fees to status quo ante for some recent year, cost disease would reverse most of that relief in relatively short order.

Clay Shirky 04.01.14 at 11:22 pm

@mdc #69:

“You really seem to be presupposing that no activity is intrinsically valuable.

Yep.

I’m with Rorty and (sorry John) against Plato in believing that there isn’t anything even approximating a summum bonum in human life. Falsifying thought experiments are a desert island away: Imagine transferring all the knowledge in Leon Fleischer’s brain and fingers to someone living on a remote desert island, someone who will never even see a piano in their life. “Intrinsic” is mainly used to me “so deeply embedded in the world I am familiar with that I fantasize that it is a universal”, while the few things that are universal like eating and sex and waste disposal aren’t great candidates for a core curriculum.

@LFC #67, you are correct that academics like to justify our labors based on some claim of intrinsic good. Like all professionals, we have a deep need to bullshit the public, lest they have the temerity to regard us as mere workers, so we dress up distribution requirements as some sentiment more lofty than “It would be good if the undergrads had some sense of how scientific inquiry differs from the profit motive as a proving ground for ideas.”