One of the people who blurbed Walkaway enthusiastically is William Gibson, whose own most recent book, The Peripheral covers many of the same themes that Walkaway does. The rise of extreme inequality described by Piketty and others, as the super-rich become so different from everyone else as nearly to be a distinct species. Accelerating technological change so that there are no jobs, or only very bad ones, for most people. A post-industrial landscape, in which the wreckage of the industrial era provides valuable resources for those in the new era.

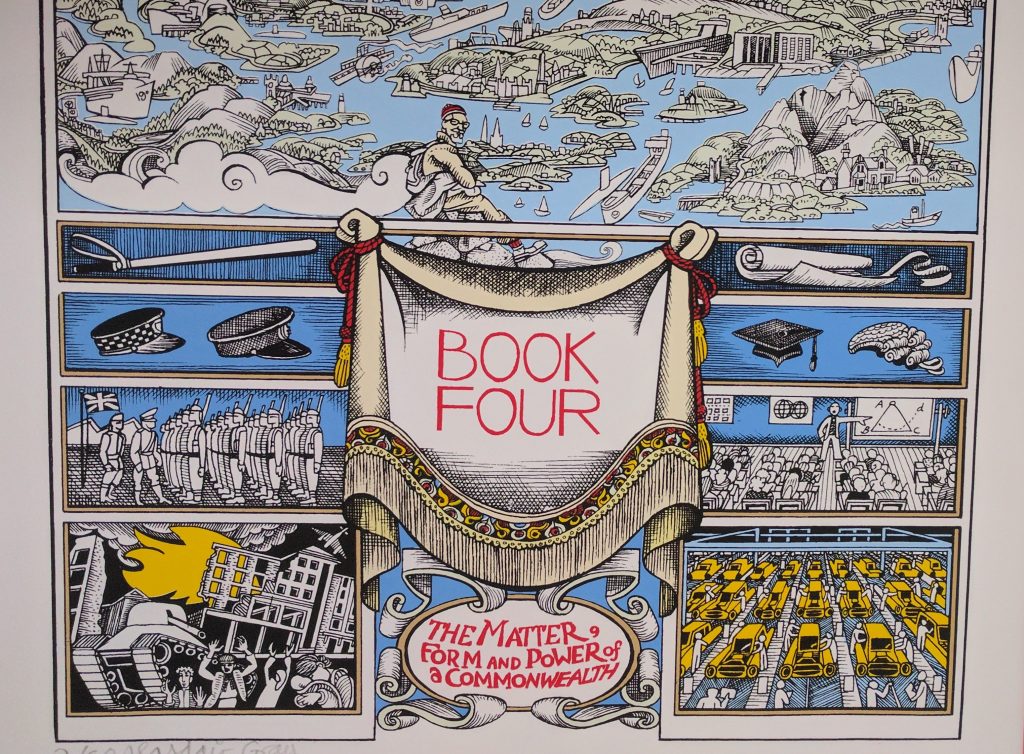

Yet the two books draw radically different conclusions from roughly similar premises. Gibson’s book is a dystopia, in which the rich are so powerful as to be, effectively, beyond challenge. The only possibilities for agency on the part of anyone else are in the interstices, the implied spaces within the structures of the internecine conflicts of the elites. Walkaway, in contrast, is a book about the beginnings of a utopia. The characters frequently quote variants of Alasdair Gray’s dictum that one should “work as if you lived in the early days of a better nation.” Above is a detail from a print by Gray, based on his frontispiece for Book Four of Lanark. It displays the forces through which the state, “foremost of the beasts of earth for pride,” maintains its domination, with the machineries of war to the left, and those of law and thought to the right. At the end of Walkaway, Doctorow’s characters live in a society which appear to have mostly escaped from both kinds of domination.

So why the different outcomes? Of course, neither Gibson nor Doctorow is setting out to predict the future, and each of their proposed worlds is an extrapolation of tendencies that exist in the present. Yet these extrapolations are disciplined – the surface matter of the story is supported by a vast, submerged and semi-visible mass of arguments about how society might change.

Gibson gives us two futures, one relatively close, the other several decades away. The first is a version of small-town America, where the economy has gotten much, much worse, so that the economy is based around illegal drug manufacture and homeland security. Fabbing has become cheap and easy, but its main disruptive impact is to make it hard for ordinary people to find work. The second is several decades on – most of the world’s population has died in a concatenation of environmental, epidemiological and political catastrophes called the “Jackpot,” leaving only the very rich, and those people who are useful to them. Nearly all the visible characters in the near future are ordinary people, trying to patch together a livelihood. Nearly all the people we see in the further future are the very rich and powerful and their immediate servants. The two futures are connected through a device that is never properly explained (the near future may be a very detailed simulation created in the far; it may be something else entirely) so that only information can pass backwards and forwards. The distance between the hyper-rich and everyone else which Gibson has been concerned with since the Tessier-Ashpools of the Sprawl trilogy has now become an ontological separation – the rich literally exist on a different order of being.

This is a world in which ordinary people have next to no agency of their own. Wilf Netherton – the viewpoint character in the further future – exists, as does more or less everyone else, on the sufferance of the rich. His status is somewhere between a higher servant and a member of a Hollywood entourage – able to enjoy relationships with the very rich, but valued primarily for his usefulness, and ultimately disposable. When his patron tells him that he has a drinking problem, and suggests he undergo treatment to fix it, he is terrified, since he has little choice but to do what pleases his better. The London that Netherton lives in is a fantastication of its current status – a tourist trap and playground for rich oligarchs and ‘klepts’ (members of kleptocratic clans), where the institutions of the City serve to make disorderly capitalism very slightly more ordinary, but are terrifying in their own right.

Doctorow’s future is not particularly pleasant for ordinary people either, but it offers many more possibilities. Again, there is a separation between the very rich (‘zottas’, since mere billions or trillions no longer serve to distinguish the truly rich from the merely affluent) and ordinary people. The former create their own secure and private enclaves, while the latter have to cope with the radical decline of regular employment, omnipresent surveillance, and a state that is increasingly willing to show the iron fist beneath the velvet glove. Yet it’s also possible to get away. The polluted world that the industrial age has left behind provides a lot of space for people who want simply to walk away from traditional society.

The toxic industrial spaces, which are exploited by the rich and their lackeys in The Peripheral (the plastic reef of the Sargasso sea is exploited by a scam masquerading as a radical body-alteration cult) provide openings, that Walkaway culture can flourish in. Fabbing allows people to turn the detritus of the industrial era into a new way of life, based around norms of solidarity and the pleasure that people get from contributing. Property is far less important in a world where people can more or less make what they need, and it’s easier to avoid conflict. If you don’t like what others are doing, you can just pick up and move elsewhere. The zottas don’t ever take really effective action against this emerging society, in part because they disagree among themselves, since some benefit from the innovations that emerge from the walkaways.

I think that the key difference between the worlds depicted in the two books is the possibility of exit. In Gibson’s book, there isn’t any exit – there is no way that one can get away from the rich and powerful. People who aren’t rich have no threat of exit because they are readily replaceable, either by other human beings or by robots (which are nearly ubiquitous). The best one can reasonably hope for is protection from a relatively benign member of the kleptocracy such as Netherton’s patron (and even then, one has to worry that he will change his mind, or grow bored, or suddenly decide that you need to radically reshape your life or ideas based on whatever new idea he’s just had). Doctorow’s book is all about exit, in the Albert Hirschman sense of the word (I don’t know whether he’s read Hirschman, but Exit, Voice and Loyalty is very relevant indeed. Doctorow’s book depicts a world in which two things are possible that are not possible in Gibson’s. First – one can create an attractive alternative society in a radically unequal world without being either squashed or suborned by the rich. Second, once this world has been created, one can move easily from regular society to the alternative.

If the two are possible, then everything else follows. If you are at the shitty end of the distribution in a radically unequal society, and your only possibilities are dead end jobs or unemployment, why not try something different, if that something different is available, and the people who have already tried it seem to be enjoying it? And if enough people try this, then it becomes impossible to maintain the machineries of oppression that Gray’s illustration depicts, since your hired coercers and indoctrinators are probably heading to the exit doors too.

Again, Doctorow’s book isn’t an exercise in predictive science – he’s not saying that things will be so. But he is saying, I think, that things could and should be so, or sort-of so. Walkaway is quite unashamedly a didactic book in the way that earlier books such as Homeland were didactic – he has a very clear message to get across. In conversations with Steve Berlin Johnson years ago, I came up with the term BoingBoing Socialism to refer to a specific set of ideas associated with Doctorow and the people around him – that free exchange of ideas unimpeded by intellectual property law and the like, together with transformative technologies of manufacture, could open up a path towards a radically egalitarian future. Unless I’m seriously mistaken (in which case I’m sure that Doctorow will tell me), Walkaway wants to do two things – to argue for why such a future might be attractive, and to suggest that something like this future could be feasible. Doctorow is very clearly picking up on a tradition of socialism present in Fourier, and (despite his animadversions against Fourier), Marx. The motivating notions of “maker culture” – that people find a profound satisfaction making things, and solving problems for their own sake, are not all that far from the young Marx’s arguments about labour and alienation. This passage explicating the Critique of the Gotha Program in Peter Frase’s Four Futures (which cites Doctorow’s books extensively) is as close to Doctorow as makes no difference.

Most of us are so accustomed to capitalist relations of production that it is hard to even imagine individuals who are not subordinated to the “division of labor.” We’re used to having bosses who devise plans and then instruct us to carry themn out; what Marx is suggesting is that it is possible to erase the barriers between thsoe who make plans for their own benefit and those who carry them out – which would of course mean erasing the distinction between those who manage the business and those who make it run.

But it also means something even more radical: erasing the distinction between what counts as a business and what counts as a collective leisure activity. Only in that situation might we find that “labor has become not only a means of life but life’s prime want.” In that case, work wouldn’t actually be work at all any more, it would be what we choose to do with our free time. … Marx’s critics have often turned this passage against him, portraying it as a hopelessly improbable utopia. What possible society could be so productive that humans are entirely liberated from having to perform some kind of involuntary and unpleasant kinds of labor? … widespread automation … could enact such a liberation or at least approach it – if, that is, we find a way to deal with the need to secure resources and energy without causing catastrophic ecological damage.

As Frase notes, the demise of wage labor “was once the dream of the Left.” Doctorow is reviving that dream.

The hard questions involve the possibility conditions for that dream. First, it may very well be that one can’t build an attractive alternative: that the utopia would crash, as others have in the past. Perhaps human beings aren’t cut out to behave in the appropriate ways enough of the time, or at scale. Indeed, one of the themes of Walkaway is that utopia is persistent and unavoidable hard work. Even drudgery can be made fun (as long as one is perpetually looking to improve and optimizing it), but cultivating the necessary habits of keeping stuff going without self-aggrandizement requires a lot of thought and introspection. Perhaps the informational demands are too high for a non-cash economy. One of the implications of a world of fabbing is that economic coordination may be less important than in the past, since large level exchange is less necessary. People can build a whole lot of what they need for themselves. Still, some mechanisms of coordination beyond distributed volunteering may be essential. Finally, it might be that abundance results in radically increased rather than decreased hierarchy (call this the A for Anything equilibrium).

It also may be that exit is far harder than it is in Walkaway. Doctorow depicts a world in which extreme inequality is coupled with high exit opportunities. The zottas take piecemeal action, but they never properly coordinate against Walkaway society until it’s too late. Yet as Gibson’s future suggests, it may be that the correlation goes the other way, so that the attractiveness and availability of exit are negatively correlated. The more unequal a world is, the more (putatively well informed) people at the bottom of the distribution would prefer another alternative, yet the less likely it is that such alternatives will be available, since the people at the top of the distribution will have forestalled or suborned most of the people who might otherwise have come up with one. None of the people in Gibson’s twinned futures are particularly happy, yet none can see any other possibilities.

Yet an exclusive focus on the plausible reasons why it Surely Could Never Work may obscure the value of Doctorow’s utopia. As per Erik Olin Wright, we don’t really know what the possibility conditions are in advance.

there is no map, and no existing social theory is sufficiently powerful to even begin to construct such a comprehensive representation of possible social destinations … Instead of the metaphor of a road map guiding us to a known destination, perhaps the best we can do is to think of the project of emancipatory social change as a voyage of exploration. We leave the well-known world with a compass that shows us the direction we want to go, and an odometer which tells us how far from the point of departure we have traveled, but without a map which lays out the entire route from the point of departure to the final destination.

and, as per Francis Spufford in a previous Crooked Timber seminar, we need a picture of what’s at the destination if we are to start even searching for it.

Finally, a point about rhetoric. If we’re deciding instead that, like all panaceas, wildly overpraised at first and then shrinking to the size of their true usefulness, Kantorovich’s insight has a future as something more modest, a tool of human emancipation good for some situations but not others – and aiming too for a more modest (and safer) politics that gains the more human world of our desires in pragmatic stages, which is what Cosma ends up with, and George Scialabba has found in the Nove-Albert-Schweikart nexus – then we have a presentational problem. It’s a lot easier to build a radical movement on a story of tranformation, on the idea of the plan that makes another world possible, than it is on a story of finding out the partial good and building upon it. The legitimacy of the Soviet experiment, and of the ecosystem of less barbarous ideas that turned out to tacitly depend upon it, lay in the perception of a big, bright, adjacent, obtainable, obvious, morally-compelling other way of doing things. Will people march if society inscribes upon its banners, ‘Watch out for the convexity constraints’? Will we gather in crowds if a speaker offers us all the utopia that isn’t NP-complete? Good luck with that. Good luck to all of us.

Good luck indeed. We’re all going to need it.

{ 19 comments }

William Timberman 04.25.17 at 5:14 pm

Lovely bit of contemplation, Henry. It hits all the high points — and low ones as well — in this emerging reshuffle of the socialism or barbarism dilemma. Are we going to end up in an egalitarian society all watched over by machines of loving grace, or is the latest iteration of our hope for technological salvation simply the final delusion of a species destined to smother the planet which gave birth to it? Don’t know, do we?

Even so, it’s comforting to think of ourselves as stewards-in-waiting, especially when compulsively checking our news feeds every morning to see who the baboon in the White House has been bombing — figuratively, or literally — while we slept. To behave as an optimist these days, you have to shorten your antennae and get on with such business as you can still conduct. Eyes on the prize, perhaps, but as the saying goes, first do no harm….

bianca steele 04.25.17 at 5:59 pm

I might quibble with this and possibly should reread, but any what I’m growing tired of with this genre of books (roughly “SF books that Farrell or Frase might recommend”) is the sameness of the vision. The narrative hints at this or that individuality of a character or situation but this is ultimately irrelevant. It’s about enough to send one back to the mainstream novel of minutely observed differences in emotional reaction to a handful of standard situations. Gibson’s better books (including The Peripheral) might come close to escaping this, but I’m not convinced they can.

Henry 04.25.17 at 6:30 pm

You might like Ruthanna Emrys’s new Winter Tide which is very much character driven (if the paradox of me recommending a book that arguably doesn’t belong to the ‘genre of books that Farrell would recommend’ isn’t too innately annoying).

More generally, some books are good to think about societies with, some to think about individuals with, and a few are good for both. The seminars we organize emphasize books of the first and third class, since those are the books most amenable to the tools that we have to hand in a blog that spans the social sciences, philosophy and fiction. But obviously, books of the second variety are great (even if, very often, the only critical response I personally can muster is to be able to point and say ‘See! Look how great that is’, which isn’t all that useful).

Donald A. Coffin 04.25.17 at 7:38 pm

I have Gibson’s book, but have yet to read it. So I probably shouldn’t comment. But one thing struck me, rather forcefully, as requiring some explanation:

“The second is several decades on – most of the world’s population has died in a concatenation of environmental, epidemiological and political catastrophes called the “Jackpot,†leaving only the very rich, and those people who are useful to them. ”

I’m trying to imagine “the very rich” in such a society. To be “very rich,” I think, means you have command over resources and, more importantly, command over the output that can be, and is being, produced. To have a “very rich” class of people implies the existence, again, it seems to me, of a very much larger group of people who work to produce the riches that the rich enjoy. (Unless, of course, if in this future, while people did not survive an army of robotic workers did.)

So I’d better read it and find out.

bianca steele 04.25.17 at 7:51 pm

Henry,

I didn’t mean to sound dismissive. I liked The Peripheral, which I learned about from your post (the only recommendation of yours I haven’t liked so far is most of Stross). But all these start to sound the same–The Peripheral, The City and the City, Walkabout, for that matter Oryx and Crake–they all seem to be about the same (small) question of divisions between rich and poor. Apparently we all have the same relationship to the same state in the same way by way of the same kinds of institutions, and that isn’t likely to change even a hundred or so years into the future. I have to wonder what there is left to learn by reading yet another of these, or whether what these books might teach about our society isn’t drowned out by the sense (certainly unfair but hard to avoid) that the authors are reading textbooks and translating them directly into imaginary worlds, then finding characters and things to fit those theories.

As the alternative, I had in mind, actually, something like The Girls, which is also about tenuous interactions between rich and poor. Or maybe Mantel’s Vacant Possession. Something where it’s possible to look at the story and see “yes, I see what this is saying about our society,” not just “yes, I’m sure all societies are kind of like that, though I’m not able to figure out the relevance to the one I live in.” Or I’m currently reading The Poisonwood Bible, which is a different way of approaching it yet again.

Russell L. Carter 04.25.17 at 7:56 pm

It sure looks to me that it’s not the 1% who are going to select our future. Rather, a big chunk of voters, across multiple countries, often reaching more than 50%, seem to be just fine with spiraling downward into plutocratic dystopia. I include the significant chunk of non-voters in that club.

How would any future utopia avoid the myriad methods of failure that all previous utopias have explored? In particular, a zero cost-to-entry utopia seems likely to fall apart along the “first in/latest in” fault lines erupting all over the world today.

People suck. Can’t get around it.

bianca steele 04.25.17 at 11:52 pm

Oops, I didn’t scroll down far enough and didn’t realize you were running another seminar. Sorry for the hijack.

chris heinz 04.26.17 at 2:31 am

I think the far more relevant comparison is to Kim Stanley Robinson’s “New York 2140” which came out earlier in April. I was fortunate enough to score a prerelease copy of “Walkaway” from an old friend who owns a bookstore about a month ago, so I read “Walkaway” immediately followed by the KSR.

I wrote up my comments, including a comparison of the 2 novels, today.

http://portraitofthedumbass.blogspot.com/2017/04/walkaway.html

MFB 04.26.17 at 9:50 am

I’ve always liked Gibson, and did enjoy The Peripheral — which, of course, offers the potential avoidance of the catastrophic extermination of the human race as a consequence of Gibson’s deus ex machina psychological time travel. It’s a bit like The Terminator in that regard, at least in its way of addressing the problem.

However, I do think that Gibson is posing a real problem. The global surge in inequality shows no sign of rolling back, nor do those in charge show any sign of wishing to diminish their control over society (the contrary seems to be true). In which case, if you are correct in your analysis of Doctorow’s book (which I haven’t read) then Doctorow is almost certainly mistaken. It is only possible to walk away from the system if the system is willing to permit you to do so, and that usually means that you pose no threat to the perpetuation of the system.

That doesn’t mean that there is no exit, of course. It means, however, that the exit would require some kind of collective political resistance to the system, to perceiving it as oppressive and being willing to take risks to directly undermine and ultimately destroy it. This, it seems to me, is something which Gibson doesn’t want to do, and it seems that Doctorow doesn’t want to do it either.

In which case, the only exit would be in something like the fall of the Roman Empire, or in our case the catastrophic diminution of transport and power generation infrastructure due to non-maintenance and resource depletion. However, that would merely take us back to a kind of feudalism, as in the last chapter of David Mitchell’s The Bone Clocks. It’s not a realistic exit unless we go all the way back to hunter-gatherer society.

Henry 04.26.17 at 11:42 am

Bianca – no worries and no offense taken – I thought you raised a real point and was responding to it.

bob mcmanus 04.26.17 at 8:15 pm

I am trying to understand these worlds of great unequal wealth without labor. What is this wealth like, how is it enjoyed? Or how is it generated and maintained? I think one of Marx and Engels basic premises is that in the history of class struggle, the pleasure of wealth is exactly the privilege of exploiting labour, whether it be Pyramids, the metropolis of Chang’an, or Versailles. After socialism, hyperabundance in eliminating labour exploitation also makes wealth inequality passe. Luxury alone isn’t enough, it’s boring, the wealthy also want adulation and power expressed in monuments and war. The artists and court poets and other servitors are too easy.

The sociology and economics are encountering a strong inarticulate resistance here.

Neville Morley 04.27.17 at 7:07 am

@Bob #11 and your comment on the Obama thread re “resignation to feudalism”. My feeling is that there’s room for debate over how far far authors like Doctorow and Gibson are proposing this combination of post-scarcity and hyper-inequality as a serious prediction of future developments (“resignation”) and how far they’re imagining this scenario as a means of reflecting on our present situation and how (whether) we can escape it, as Henry discusses. Yes, the general intellectual mood seems to be pessimistic, if not completely resigned: the sense, in Piketty or in Walter Scheidel’s new book on inequality and violence, that the C20 narrowing of inequality, limited as it was, may be a historical aberration, and in the long run, absent massively destructive war, the rich keep getting richer. Arguably, the role of science fiction is to make bigger imaginative leaps in thinking about possible alternatives, rather than just accepting the present state of affairs as normal.

My direct experience of the rich is pretty well negligible, but instinctively I wonder about your argument that they will always yearn for popular acclamation, monuments, honour etc. In the old days, yes – I spend most of my time studying pre-modern oligarchies in which this is the dominant dynamic, giving at least a limited degree of leverage to the masses. But my fuzzy sense is that this is much less true today; partly because the rich have captured and/or neutered the state and mainstream media so have less need to placate the masses, partly because status at this rarified level seems to be based much less on ‘honour’ and much more on market worth and conspicuous consumption, displayed not to masses but to fellow members of the elite. They can carry on competing with another indefinitely on those terms. Put another way, one occasionally sees lists of the wealthy, and thinks: who knew there were so many, and who the hell are these people? They’re not just different, they’re increasingly separate.

Neville Morley 04.27.17 at 7:15 am

And again: do Marx and Engels present exploitation of labour as source of pleasure, rather than just means to end? I can see how it could be source of social status, in Weberian terms – but certainly not the only possible source, and so a society in which exploitation becomes largely redundant doesn’t automatically become a society free from hierarchy.

bob mcmanus 04.27.17 at 12:10 pm

I feel ignorant, forgetful, and stupid. I kinda feel that my questions or confusion will not only be covered by the books and seminar, but are the point of the books. I should wait and read.

do Marx and Engels present exploitation of labour as source of pleasure

1) I don’t remember if M & E discuss the motivations for accumulation as much as the process, which feeds itself once started. I vaguely remember that ME characterize humans as enjoying work (not paid labour), manipulating the environment, homo faber.

2) Define wealth. Wealth is not luxury or well being. Wealth is social differentiated accumulation, relative, competitive. If gold flowed like water, nobody is going to be impressed by how much gold you have, and gold ceases to be valuable except as use value.

3) I reread the first two sections of the Peter Frase last night. Yes, communism will have hierarchies and competition, status seeking. Frase says his second scenario, hierarchy plus abundance, is likely to be unstable, because of a lack of demand, and resolve to communism. Umm.

4) We have no shortage of rentier economies (or subcultures) to remember. With trepidation in presence of Morley, I try to remember Greece and Rome, and de Ste Croix, of course immersed in exploited labour (slaves and women), and had a citizen class, not wealthy, who were idle and content? Go Blues.

5) I keep coming back to a LTV. The fine kimono, the parquet floor, the Go master or great cellist are all forms of exploited or remunerated labor. The Monet is a little more difficult, but a Monet is valuable because of an environment and history of lesser paintings.

6) I guess my question is that as long as there is competition for wealth and a desire for inequality, will a massive and obvious source of value, labour, be left idle and unexploited? The wealth and inequality provide, almost by definition, the motivation and the means (Frickian hiring half the workers to oversee the other half).

Inequality, not scarcity, drives exploitation.

Neville Morley 04.27.17 at 1:22 pm

Thanks for that, Bob. On reflection, I think my comments focused almost entirely on why inequality would continue to exist rather than how. In a proper post-scarcity society, as you say, gold flows like water and ceases to have value, and we head into the Banksian Culture where status is based on trivial things like descent from Founders and has little real-world impact, where it’s not actively frowned upon. Doctorow’s future still has status and inequality, so ipso facto it isn’t fully post-scarcity, even with existence of fabbing. Not sure how that works either. Importance of code to run the machines, hence wealth based on control and exploitation of intellectual property?

I guess my answer to the “if there’s labour to exploit, why not exploit it?” question is: because there are costs and risks involved. Roman slave owners worried about costs of supervising slaves and problem of having to rely on other slaves to do this; they’d happily have signed up to the Rise of the Robots. Incidentally, I’m of the persuasion that doesn’t believe in the existence of an idle and contented citizen class, though there’s definitely a hierarchy of wealth within the mass of the population in antiquity, not just mass versus elite.

bianca steele 04.27.17 at 1:29 pm

I haven’t read Hirschman, but the idea that loyalty precludes voice has always bothered me, as if voice was just a dishonest trying to have it both ways. Or that “resignation” is never an option, either. I’m tempted to suggest that “neoliberalism” is at fault in making us think the only conflict that matters is who has more money (of course it goes back earlier, probably no matter what you choose a precursor can be found). The bar for persuading people that another thing is in play appears to be very high, with no communication across it to speak of. At any rate these dystopias all apparently assume voice is just not an option, it would seem paradoxically since the authors are writers. Or at least that the line between voice and violent opposition is incredibly narrow.

Paul 04.27.17 at 1:42 pm

Bob: just noting, yours is the “evil is the root of all money” argument.

William Timberman 04.27.17 at 2:37 pm

Messrs mcmanus and Morley @11, etc.

Weber has been mentioned, and rightly so. Shouldn’t Veblen get a shoutout as well? Steve Bannon is desperate to be thought a genius precisely because he isn’t one. Einstein, in his later career, at least, didn’t seem to care at all how he was regarded. It’s as though the work alone provided all the satisfaction he needed, and the fact that it also provided him with sufficient income to get on with his passion must at times have seemed like something of an accident, or in any case not something to be overly concerned about.

Reputation as a commodity is an interesting concept, but as Trump and the Kardashians amply demonstrate, it’s an extremely volatile one. Shepherding the value of one’s own stock of it seems to be an all-consuming task, not one that a sane person would want to devote his life to.

Maybe it’s because I’m old, but gold curtains in the White House, or tenure at Harvard, for that matter, seem a bit threadbare as signaling devices. We are what we are, do what we do. It would be nice to live in a society in which that would be possible without the risk of starvation, violence, or exploitation, but the social stability which permits it for some of us seems to be another one of those hard-won and inherently unstable commodities. As the man said, the fault, singular or plural, is not in our stars, but in ourselves.

Matt 04.27.17 at 9:03 pm

However, I do think that Gibson is posing a real problem. The global surge in inequality shows no sign of rolling back, nor do those in charge show any sign of wishing to diminish their control over society (the contrary seems to be true). In which case, if you are correct in your analysis of Doctorow’s book (which I haven’t read) then Doctorow is almost certainly mistaken. It is only possible to walk away from the system if the system is willing to permit you to do so, and that usually means that you pose no threat to the perpetuation of the system.

This is one of those blind spots about almost-post-scarcity futures that is easy to fall in to if you live in a high-income country. Much of the world’s population lives in countries where there is no direct reason for local power brokers to favor the kind of restrictive intellectual property systems favored by the EU/US. There is precious little direct reason for Bolivian or Indian companies, politicians, or plutocrats to favor lengthy and highly restrictive copyrights or patents. To the extent that poor nations without multinational pharma, cutting edge technology, and entertainment businesses comply with EU/US wishes about intellectual property, it’s due to a combination of carrots and sticks wielded by the richer regions. And sometimes that still isn’t enough; witness poor countries with patients in need ignoring drug patents when necessary.

What happens when fabbers render export-driven development unattractive, both because rich consumers no longer need imports and local development can proceed faster if you skip the middle man and steal fire (fabbers) from the gods? Then the developing world can tell the rich world to go piss up a rope when it comes to IP restrictions. And the rich world can retaliate financially and with trade restrictions, but: they’re just threatening to take away what you no longer want. Why chase the mirage of development — financing and trade — when you could just develop right here, by freely copying what works? Doctorow has previously imagined a scenario where people do that and the ownership class goes to war against the information “thieves” (After the Siege). But I think that works better as satirical commentary on the present than as futurology. The US can’t successfully keep even one occupied country under control at a time. Invading/occupying every low-income country that ignores US IP restrictions? Some of which have nuclear weapons? It’s not going to happen. Not even if the head of the MPAA is elected President and the Senate is composed exclusively of executives from Oracle, Monsanto, Merck, and Microsoft.

Comments on this entry are closed.