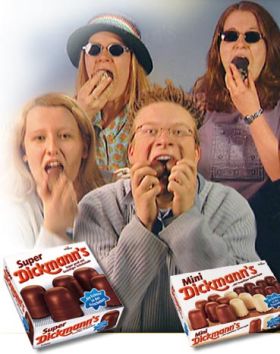

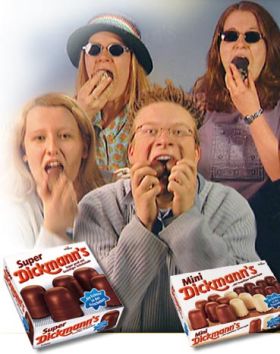

Matt Yglesias is amazed that you can buy a coconut-flavoured candy called ‘Super Osama Kulfa Balls’ in China. There’s worse to be found in every German supermarket that I’ve ever been in …

Matt Yglesias is amazed that you can buy a coconut-flavoured candy called ‘Super Osama Kulfa Balls’ in China. There’s worse to be found in every German supermarket that I’ve ever been in …

Adam Swift and I have just posted a short critical working paper at the Center for the Study of Social Justice website. It’s a response to papers in Ethics (July 2007) by Elizabeth Anderson and Debra Satz (both, I’m afraid, behind a paywall, though I notice that the free sample issue is the one with Adam’s and my paper on parents rights, so I can’t resist encouraging people to read that), both arguing for a principle of educational adequacy as the correct principle of educational justice. Before reading their papers I had thought of adequacy as a straightforward strategic retreat by educational progressives, a retreat that makes strategic sense in the US because many States have constitutional provisions that are plausibly interpreted as demanding adequacy for all (and litigation, not politics, is the most promising way forward). But both Satz and Anderson argue for adequacy on principled grounds; they think that educational equality is a misguided goal, and also that adequacy is a good goal. There’s a great deal of good stuff in both their papers, so I strongly recommend them (if you can get at them). Satz is especially good on what adequacy, understood the right way, demands for low-achieving children, whereas Anderson is especially good on what it demands for children bound for elites; basically, her argument is that an adequate education for them requires that they have a lot of interaction with children from other social backgrounds so that they are well prepared for their roles in the elites they will join (which are justified, in Rawlsian terms, by their tendency to benefit the less advantaged). Our paper doesn’t dispute the importance of adequacy as part of the picture, and an urgent one at that, but responds to their anti-equality arguments, showing that they depend on (wrongly) interpreting equality as the sole principle of educational justice (in fact it is one among several principles, and not necessarily the most important); but also arguing that adequacy does not offer the right guidance in some circumstances. Comments welcome.

How utterly depressing to surf over to Amanda’s excellent site only to discover that Arlo Guthrie has endorsed Ron Paul . I thought I’d wash this out of my head by listening to his father singing Plane Wreck at Los Gatos. Guess what? There’s not a clip of Woody singing it at Youtube, but there is one of Arlo covering it with Emmylou Harris. Did the man not listen to the lyrics? May he die of shame if he ever sings it again.

As many readers of this blog, I frequently receive requests from academic journals to referee papers. Sometimes refereeing a paper creates benefits for the referee (like reading an interesting argument or getting inspiration for a new project), but on balance I find referee work a burden. Still, I do a lot of it (I think), since I consider it a duty of any scholar who is sending manuscripts to journals.

How much should we referee? If I were to accept all referee requests that I get, I would hardly be able to do any research myself. So I want to find out how many papers I should referee before I have fulfilled my professional duty. In the last months, I talked to some (international) colleagues about how much they referee and how they decide whether to accept or reject a referee request, and I’ve discovered that some of them don’t find it difficult at all to refuse to referee virtually all the requests they get. Not me: I feel bad every time I turn down an editor (but I’m getting better at it!). Surely there is some sort of collective action problem here, since the system can only be sustained if enough people do referee; so I feel anyone who wants to be part of this system (that is, who submits papers to refereed journals), should feel a professional duty to referee. I think one should referee at least the same number of papers as the number of reports one receives; so if in the last 12 months you’ve received 10 reports, you should referee at least 10 papers in the same period (if asked and if you feel competent to referee them, of course). I’ve been told that this rule was once suggested at a meeting of editors at the APSA meetings – and it makes perfect sense to me. Perhaps we should add 10% or 20% as a margin, since there will be people who submit papers but are not yet being asked to referee, as they are not known by journal editors as potential referees.

Since we have several journal editors among our readers, I’d like to ask: how difficult is it these days to find (good) referees? And if you’ve been in the business for some time: is it getting easier or harder to find good referees? And to anyone who feels like commenting: what do you think of the above rule to decide when we’ve done our fair share of refereeing — any better proposals?