by Kieran Healy on July 17, 2011

Via Chris, on Twitter (I hope I’m not preempting him here), an Open Letter from a Keynesian to a Marxist by Joan Robinson, and “Zombie Marx“, an essay by Mike Beggs. Here is Robinson, writing in 1953:

I was a student at a time when vulgar economics was in a particularly vulgar state. … There was Great Britain with never less than a million workers unemployed, and there was I with my supervisor teaching me that it is logically impossible to have unemployment because of Say’s Law. Now comes Keynes and proves that Say’s Law is nonsense (so did Marx, of course, but my supervisor never drew my attention to Marx’s views on the subject). … The thing I am going to say that will make you too numb or too hot (according to temperament) to understand the rest of my letter is this: I understand Marx far and away better than you do. (I shall give you an interesting historical explanation of why this is so in a minute, if you are not completely frozen stiff or boiling over before you get to that bit.) When I say I understand Marx better than you, I don’t mean to say that I know the text better than you do. If you start throwing quotations at me you will have me baffled in no time. In fact, I refuse to play before you begin. What I mean is that I have Marx in my bones and you have him in your mouth. … suppose we each want to recall some tricky point in Capital, for instance the schema at the end of Volume II. What do you do? You take down the volume and look it up. What do I do? I take the back of an envelope and work it out.

And here is Beggs:

There are generations of economists who would call themselves Marxists, or admit Marx as a major influence, who have … engaged with other strands of economic thought and folded them into their worldview, have worried little about dropping from their analyses those aspects of Marx’s argument they believed to be wrong or unhelpful, and have felt no need to pepper their writing with appeals to authority in the form of biblical quotations. But in each generation, there are others who have defended an “orthodox” Marxian economics as a separate and superior paradigm, which can only be contaminated by absorbing ideas from elsewhere. … If we are to engage in these ways with modern economics, what, if anything, makes our analysis distinctively Marxist? It is the two-fold project behind Capital as a critique of political economy: first to demonstrate the social preconditions that lie beneath the concepts of political economy, and especially their dependence on class relationships; and second, to demonstrate these social relations as historical, not eternal. These two strands of Marx’s thought are as valid as ever. The way to apply them today is … is to deal not only, not even mainly, with economic high theory, but also with the applied economics produced every day in the reports and statements of central banks, Treasuries, the IMF, etc., and ask, what are the implicit class relations here? Why are these the driving issues at this point in history? What are the deeper social contradictions lying behind them? The pursuit of a separate system of economics as something wholly other from mainstream economics isolates us from the political and ideological space where these things take place: better, instead, to fight from the inside, to make clear the social and political content of the categories. A side effect is that we learn to think for ourselves again about how capitalism works, to be able to answer the kinds of question DeLong raised against Harvey, no longer lost without the appropriate quotation.

by John Q on July 17, 2011

The political impregnability of Rupert Murdoch and NewsCorp has always been one of those facts about the world that seemed regrettable but eternal. By contrast, the ability of the banks to emerge from their near-destruction of the world economy richer and more politically powerful than ever before certainly took me by surprise when it happened (partly motivating my change in title from “Dead Ideas” to “Zombie Economics”). John Emerson pointed out the other day that the head of risk management at Lehman Brothers, arguably the most egregious individual failure among the thousands of examples, was just appointed to a senior position at the World Bank.

But now it seems there is just a chance that the curtain might be swept away from even these wizards. The emerging theme in commentary is the corrupt culture of impunity represented by the press hacking scandal, MP expenses and the banks (here’s Ed Miliband pulling them all together).

If Labor could tie the Conservative-Liberal austerity package to the protection of the systemically corrupt banking system, they would have the chance to put Nu Labour behind them (I noticed Blair has already credited Brown with killing the brand). Instead of putting all the burden on the public at large, they could force those who benefited from the bubble to pay for the cleanup. The two main groups are the creditors who lent irresponsibly, counting on a bailout and should now take a long-overdue haircut and high-income earners who benefited, either directly or indirectly, from the huge inflation in financial sector income.

I know it seems hopelessly naive to think the banks could ever be brought to heel. But they were, for decades after the Depression. And as impregnable as they look today, Newscorp looked just as impregnable three weeks ago, as did the CPSU and the apartheid regime in South Africa thirty years ago.

Of course this spring moment won’t last long. But perhaps there is enough momentum that it won’t be exhausted by Murdoch alone.

[click to continue…]

by Henry Farrell on July 15, 2011

Rupert does his first post-crisis interview, with “the Wall Street Journal”:http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052702304521304576446261304709284.html, naturally.

bq. In an interview, Mr. Murdoch said News Corp. has handled the crisis “extremely well in every way possible,” making just “minor mistakes.”

Indeed – News Corporation has done a quite wonderful job handling the mess – with a few, notably rare exceptions.

Should anyone be interested I did a “Bloggingheads”:http://bloggingheads.tv/diavlogs/37406 yesterday with Felix Salmon on the Murdoch scandal and a few related topics (this in turn led to a couple of talking-heads type appearances on BBC channels today, but I really can’t think I said anything in my allotted 90 second slots that’s surprising enough to be worth hunting down).

by niamh on July 14, 2011

I’ve been wondering when best to air some thoughts about the ongoing public protests in Spain and Greece. The moment never seems right, because there’s always some bigger crisis about to break in European politics. The markets have turned on Italy;  Ireland joins Portugal in the junk box, despite meeting all its targets; European leaders remain divided on what should happen; they may or may not hold yet another summit this week.

But as long as the countries that have been worst hit by crisis are required to impose continuous austerity policies in the present climate, something deeper may be happening to public opinion, to civil society, and to the framework of consent to be ruled in a particular way.

These are not fixed things of course. They shift and evolve in response to the balance of power, the dominant ideas, the credibility of pain- and gain-sharing plans, the institutionalization of compromises through particular policy commitments.

I was in Barcelona recently and saw some of the mass protests in the Plaça de Catalunya, which have been replicated this summer in cities across Spain. Not much was going on around the camp in the daytime, but the place came alive by night, with speeches, singing, dancing, lectures, films, and at the weekends, larger protests against the government’s policies.

This is not a trade union protest; these are not public sector employees. So who are the protesters, the ‘indignatos’ who have been occupying Spanish public spaces? The numbers out on the squares are going down a bit now, but their social networking links are expanding enormously. And in Greece, who are the people taking part in street protests, which now seem to take on an almost ritualized form, parallel to but not the same as public sector strikes? What does it all mean for our understanding of democracy in hard times?

[click to continue…]

by Chris Bertram on July 13, 2011

With the news that the BSkyB bid has been withdrawn, a pretty amazing week in British politics (with ramifications beyond) seems to have come to a climax. Ed Miliband, the Labour leader, who had, frankly, looked pretty hopeless only a few days ago did a superb job on the Tories and the Murdoch empire, and kudos to people like Tom Watson and Chris Bryant who have had the courage to stand up to a threatening and vindictive organization and respect also to the great journalist who really cracked it, Nick Davies. Hard to know what the future holds, because so many of the assumptions recycled by Britain’s lazy commentariat depend on the fixed notion that Britain’s politicians have to accommodate themselves to Rupert Murdoch (that Overton Window thingy just changed its dimensions). Even the erstwhile victims of Stockholm Syndrome, like Peter Mandelson, are now declaring that they were always privately opposed. Well of course! Enjoy for now.

by Henry Farrell on July 12, 2011

I’m now on the executive committee of SASE, the Society for the Advancement of Socio-Economics, which is a kind of professional organization for economic sociologists and hangers-on like me. The organization’s annual meeting was in Madrid this year, and will be in Boston (at MIT) next year. One of the more interesting features of SASE meetings is that you can propose ‘mini-conferences,’ where you propose a theme around which a number of linked panels can be arranged. Hence my desire to let CT readers know about the “request for proposals”:http://www.sase.org/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=322&Itemid=46. Proposals are due by September 1; the 2012 overall conference theme is “Global Shifts: Implications for Business, Government and Labour” which should, I imagine, intersect nicely with the interests of a lot of CT readers.

by Henry Farrell on July 11, 2011

As a quick addendum to John’s post, it’s worth remembering that Alex Tabarrok got “quite upset”:http://marginalrevolution.com/marginalrevolution/2007/08/dani-rodrik-has.html a few years ago, when Dani Rodrik “suggested”:http://rodrik.typepad.com/dani_rodriks_weblog/2007/08/irreconcilable-.html that he and other libertarians were anti-government ideologues who had immunized themselves against countervailing evidence.

bq. Dani Rodrik responds here to my pointed remarks on his argument for industrial policy. Rodrik’s response, however, is along the same lines of his earlier – “I’m sophisticated, you’re simplistic” – post on why economists disagree. In this case, it’s ‘libertarians are ideologues who are immune to evidence.’ Rodrik, however, has painted himself into a corner because he cannot at the same time say that the “systematic empirical evidence” for market imperfections in education, health, social insurance and Keynesian stabilization policy is “sketchy, to say the least” (also “difficult to pin down” and ‘unsystematic’) and also claim that libertarians are ideologues who are immune to evidence. Say rather that libertarian economists are immune to sketchy, unsystematic, difficult to pin down evidence. Rodrik is thus right that he is “not as unconventional as I sometimes think I am. The real revolutionaries here are the libertarians.” The libertarian economists are revolutionaries, however, not because they are immune to evidence but because they respect evidence so much that they are unwilling to accept “conventional wisdom” simply because it is conventional.

I’m trying really, _really_ hard to reconcile the argument that Alex and his mates are not anti-government ideologues, and indeed have far greater respect for evidence than their opponents, with his more recent “claim”:http://marginalrevolution.com/marginalrevolution/2011/07/the-great-fiction.html that:

bq. As Bastiat said, “Government is the great fiction through which everybody endeavors to live at the expense of everybody else.” What Rampell et al. want to do is to make people believe in this great fiction.

It seems to me difficult to maintain the claim that government is necessarily a communal fraud (and that the people who you disagree with are trying to make people believe in this fraud) and at the same time argue that you and other libertarian economists are open-minded individuals happy to go wherever the evidence about politics and markets takes you. But then I’m not a “libertarian economist”:http://www.cscs.umich.edu/~crshalizi/weblog/253.html.

by John Holbo on July 11, 2011

Alex Tabbarok has written an odd post, whose reasoning, were it sound, would seem to license the following inference. Since, as Bastiat says, “Government is the great fiction through which everybody endeavors to live at the expense of everybody else,” John Cleese’s fatal mistake in this debate is to admit the existence of Roman aqueducts. (That really puts him on an ontological slippery slope to sanitation and education and all manner of entification.)

But seriously. I guess I can see arguing that tax credits aren’t, per se, social programs – but aren’t they social engineering, hmmm yes? (Wouldn’t it follow that they couldn’t be faulted for being the latter, if they can’t be credited with being the former?) But I find it hard to see how 529 plans could, strictly speaking, fail of bare existence. (If you think otherwise, I’ve got a Pentagon you might like to levitate.) Arguing that if something didn’t exist, the private sector could take up the slack is one thing. But arguing that because you could – oh, say, hire a private protection outfit – that therefore the police actually don’t exist … ?

Finally, I have a feeling that Tabarrok would not, if caught in another mood, express a preference for a tax code pockmarked with various and sundry breaks, giveaways and loopholes over one lacking these features, commonly regarded as unlovely by economists. But since Tabarrok’s stated position is now that such things are rightly regarded as precious islands of civil freedom, in a socialist sea of serfdom … oh I give up.

by John Q on July 10, 2011

The ever-expanding scandal surrounding hacking, bribery, perjury and obstruction of justice by News Corporation in England has already brought about the closure of the venerable (at least in years) News of the World newspaper, but looks likely to go much further, with significant implications for the Murdoch press in Australia, where Murdoch started out in my hometown of Adelaide (I should mention that, despite being born here, Murdoch is not an Australian by either citizenship or residence. He took out US citizenshup citizenship quite a while ago to further his ambitions there) .

The scandal over hacking and other criminal behavior has now become an all-out revolt of UK politicians against Murdoch’s immense political power , which has had successive Prime Ministers dancing attendance on him, and rushing to confer lucrative favors on his News Corporation. Those, like Labour leader Ed Miliband, who are relative cleanskins, are making the running, while PM David Cameron, very close to the most corrupt elements of News, is scrambling to cover himself.

The hacking and bribery scandals appear (as far as we know) to be confined to the UK, but the greater scandal of Murdoch’s corruption of the political process and misuse of press power is even worse in Australia. The Australian and other Murdoch publications filled with lies and politically slanted reporting aimed at furthering both Murdoch’s political agenda and his commercial interests. Whereas there is still lively competition in the British Press, Murdoch has a print monopoly in major cities like Brisbane.

It seems likely that News International will be refused permission for its impending takeover of BSkyB on the grounds that it is not “fit and proper” for such a role. That would have important implications for Australia (and perhaps also for the US, though Australian regulators are more likely to be influenced by UK precedents).

Regardless of how the current scandal plays out, we need to remember that while the Australian productions of News Corporation may be papers, what they print is certainly not news.

by John Q on July 8, 2011

Another really bad employment report from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Employment has been essentially static for the last couple of months, and most of the ground gained in 2010 has been lost. Unsurprisingly, public sector job cuts are leading the way downwards, as the stimulus fades into memory and austerity proceeds at the state and local level. In this context, it’s hard to know what outcome of the current negotiations over the debt limit would be worse: unconditional surrender to Republican demands for yet more spending cuts, or a failure to pass any legislation, with consequences that remain unclear[1].It’s hard to see US unemployment falling substantially any time soon. The decline in the participation rate (it’s fallen by about 3 percentage points of the population, equal to about 5 per cent of the labor force) means that the standard measure seriously understates the severity of the problem. If employment growth were to resume, lots of people would re-enter the labor market, so that unemployment would not decline fast.

[click to continue…]

Portugal’s debt has just been downgraded to junk bond status. Ireland’s efforts to boost investor confidence are under threat; Italy is starting to look wobbly.

European politicians are openly expressing their anger at the three main ratings agencies’ oligopoly, accusing them of attempting to exercise improper influence over policy-making – the timing of their downgrades is ‘not a coincidence’, and they are ‘playing politics, not economics’.

Evidence from Ireland bears this out – there seems to be no consistency in the way the ratings agencies evaluate the decisions of governments in the Eurozone periphery. Governments are put under pressure to engage in ‘orthodox’ fiscal retrenchment, in line with the EU’s excessive deficit procedures, and as required of Greece, Ireland and Portugal in line with their IMF-EU loan programmes. But as soon as they take relevant action, they find their ratings downgraded on the ‘heterodox’ grounds that taking money out of the economy will damage growth potential. Two bodies of economic theory seem to be at work here: ‘expansionary fiscal contraction’ when the aim is to enforce cuts, Keynesian counter-cyclical policy when the objective is to punish excessive contraction. Damned if you do and damned if you don’t.

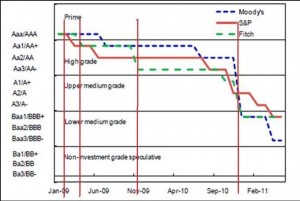

Take a look at this graph, from the IMF’s May report on Ireland.

Each of the vertical red lines I’ve added represents an ‘orthodox’ fiscal adjustment on the part of the Irish government between February 2009 and December 2010. The balance was about 65% spending cuts and 35% tax increases, entirely consistent with conventional thinking. The profile looks like this:

The overall adjustment between 2008 and2014 is €29.6bn. This would be equivalent to about 19% GDP and 22% GNP in 2010. Yet Ireland’s ratings have been consistently cut.

Very odd.

by John Holbo on July 7, 2011

by Belle Waring on July 7, 2011

This is a good post about why rape victims are likely to lie…about the circumstances of the rape in order to make their rape conform to the narrative they think the cops/prosecutors/jury needs to hear.

Thanks to prevailing rape mythology, many people also have very definite ideas about what happens before, during, and after a “real” rape. Real rape victims want no sexual contact of any kind with their attackers and make this crystal clear right from the start. When attacked, they don’t just say “No;” they scream, fight, yell for help, and/or try to escape. Ideally, the victim will duke it out with her attacker to such an extent that she is left with obvious physical injuries. After the rape, she will be visibly distraught and in tears, but this will not prevent her from reporting the attack right away. In the days and weeks following the assault, she will spend a lot of time in the shower and be too traumatized to appear to function normally.

Some rapes do indeed happen like that; most don’t. And the more a rape departs from this script, the harder it is for the victim to be believed and taken seriously. She didn’t fight or try to escape? She must’ve wanted it. She wasn’t crying or visibly upset right after the rape? She’s probably lying about being attacked. She was seen laughing and seemingly having a good time just days after being raped? It couldn’t have been that bad.

Rape victims know this. Realizing that many people won’t understand why you acted in a way that doesn’t fit their preconceived notions of “how rape victims act,” or worse, knowing that many people will automatically disbelieve you because of your background or even blame you for being attacked brings some rape victims to the conclusion that there’s only one way they’re going to see their rapist punished: lie.

[click to continue…]

by Henry Farrell on July 5, 2011

I’m at the beach and kid-wrangling, so not in any position to write long blog-posts. But I am intrigued by this “James Fallows post”:http://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2011/07/google-so-far-so-good/241426/ suggesting that Google Plus is reasonably non-privacy invasive (for values of non-privacy invasive that include all your search data etc are belong to us).

bq. One of the immediate appeals is how quick, ergonomically easy, and aesthetically nice it is to set up “circles” that match the natural patterns of your real life. One for immediate family, one for “friends you actually know,” another for “professional acquaintances who are sort of friends,” etc. Or by interest. In my case: airplane people, beer people, China people, tech people, Atlantic people, NPR people, etc. …. The other immediate appeal is that the privacy bias seems set in your favor, rather than constantly playing hide-the-ball with you, as Facebook does. The reason I hate and mistrust Facebook is its constant record of changing the privacy terms, not saying it’s done so until it’s caught, and always setting the default in the least private and most advertiser-exploitable way.

This suggests that Google Plus doesn’t have the deficiencies that “drove me away”:https://crookedtimber.org/2010/05/14/an-internet-where-everyone-knows-youre-a-dog/ from Facebook (which is not to say that it doesn’t have others). I’d be interested to hear from those who are better connected than I am, and have Google Plus accounts, whether this is true, how they find the experience, etc etc.