A book review from Inside Story: After The Spike by Spears and Geruso

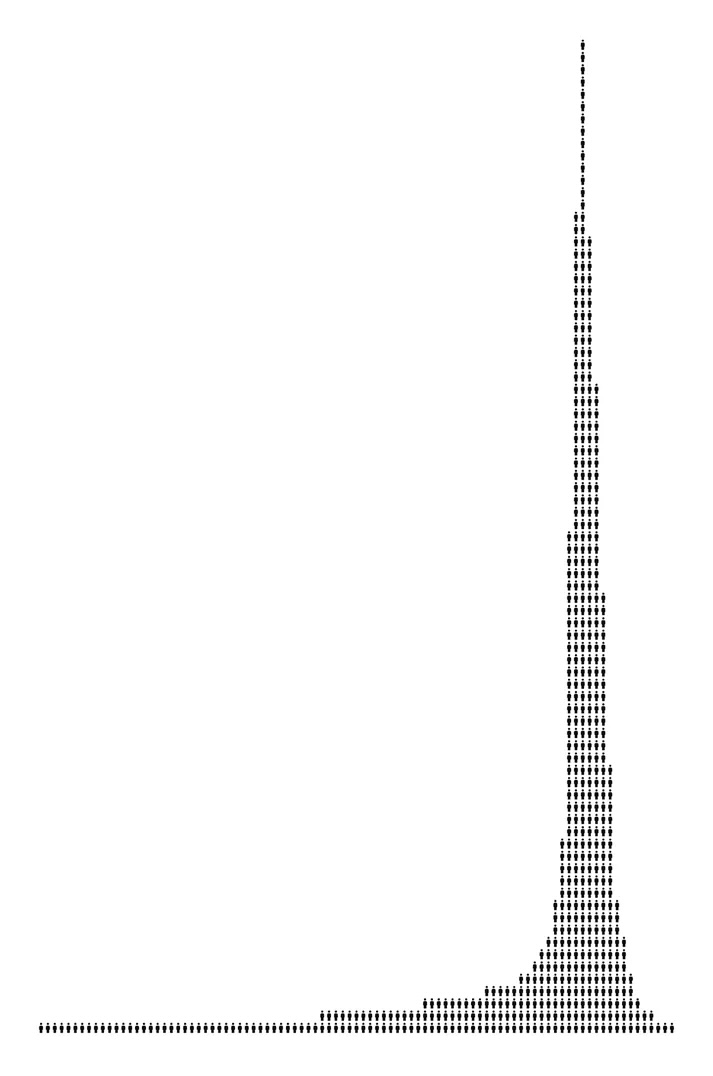

The most striking observation in Dean Spears and Michael Geruso’s new book, After the Spike, is summed up by the cover illustration, which shows a world population rising rapidly to its current eight billion before declining to pre-modern levels and eventually to zero. As the authors observe, this is the inevitable implication of the hypothesis that fertility levels will remain below replacement level indefinitely into the future.

Before looking at the argument in more detail, it’s worth recalling Stein’s Law: “If something can’t go on forever, it will stop.” If the world’s population was in danger of falling below the level needed to sustain civilisation (science fiction writer Charlie Stross has estimated 100 million) there would presumably be some kind of drastic action. Fortunately, this is unlikely to happen for another 1000 years or so. If we manage to leave the planet in a habitable condition so far into the future, we can leave population policy to our distant descendants.

Before looking to the future, Spears and Geruso consider the past. The most striking observation here is that fertility (the number of children per woman) has been declining on average ever since reliable records began several hundred years ago. This isn’t news to those who have followed the question closely.

While fertility declined steadily over centuries, infant mortality dropped drastically from the eighteenth century onwards, first in the West and then globally. While fewer children were born, more survived to adulthood.

In exploring these trends, demographers focus on the net reproduction rate, or NRR: the number of surviving daughters per woman. (We all became familiar with this number in a different context in the early days of the Covid pandemic.) When the rate is greater than 1, the population grows.

For a hundred years or so from the late nineteenth century, the NRR rose steadily, reaching a peak of 2.1 in the early 1960s. That’s enough to double the population every generation (or about every thirty-five years). Had that rate continued, the world population would now be around twenty billion. It was in this context that biologist Paul Ehrlich sounded the alarm with his bestseller The Population Bomb, which predicted global disaster as soon as the 1970s.

Spears and Geruso are justifiably critical of Ehrlich’s alarmism. In reality, they observe, we have been highly successful in feeding a growing world population. Nor have predictions of the exhaustion of mineral resources put forward by Ehrlich and dramatised by the Club of Rome been borne out.

But emissions of carbon dioxide have grown drastically, driven in part by the population growth of the late twentieth century. Spears and Geruso mention the issue, but don’t discuss the relationship to population except in the context of our present climate crisis, where (as they say) population is of secondary importance.

The big point Spears and Geruso could have made, but didn’t, is that Ehrlich was sounding the alarm just as the NRR was reaching an inevitable peak. By the 1960s child mortality rates had already been reduced to a level at which further reductions couldn’t outpace the steady decline in fertility that is the central theme of After The Spike. The NRR was bound to fall even without the drastic measures suggested by Ehrlich (and, in more extreme form, by overtly racist writers like Garret Hardin, in his Lifeboat Ethics).

Because the population boom produced a mostly young population, declining fertility didn’t immediately translate into a smaller number of babies. Concern about the possibility of a declining population emerged when the number of births peaked in 2012. This concern built on a much longer, and entirely misguided, tradition of worrying about the supposed dangers of an “ageing population.” Sensibly, Spears and Geruso downplay such concerns, observing: “Restructuring public benefit programs and retirement ages is a fast solution to balancing the books in an ageing population. Raising birth rates is a slow alternative to any of these.”

And what of the far future? Projections show that likely declines in fertility will halve the world population each century after 2100, falling to one billion around 2400. Would that be too few to sustain a modern civilisation ?

We can answer this pretty easily from past experience. In the second half of twentieth century, the modern economy consisted of the member countries of the Organisation For Economic Co-operation and Development. Originally including the countries of Western Europe and North America but soon extended to include Australia and Japan, the OECD countries were responsible for the great majority of the global industrial economy, including manufacturing, modern services and technological innovation.

Except for some purchases of raw materials from the Global South, the OECD, taken as a whole, was self-sufficient in nearly everything required for a modern economy. So the population of the OECD in the second half of last century provides an upper bound to the number of humans needed to sustain such an economy. That number did not reach a billion until 1980.

Things have changed since then with the modernisation of much of Asia and the rise of China as the manufacturing’s “workshop of the world.” But the history is still relevant.

We can also look at the United Sates. Even today, trade accounts for only around 20 per cent of US economic output. Given a US population of 400 million, it is reasonable to suppose that the production of goods and services elsewhere for export to the US might account for another 100 million people. Most of the needs of these people could be met from within the US economy, but let’s suppose that they employ another 100 million in their own countries. That’s still only about 600 million people who, between them, produce all the food they need, the manufactures that characterised the industrial economy of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, most of the information technology the world relies on, and a steady flow of technological and scientific innovation.

At the lower end of the scale, Stross’s estimated minimum requirement, 100 million people, might need to be higher in a society even more technologically complex than our own. But since current demographic trends won’t produce that number for nearly a millennium, we probably needn’t worry (unless we want to colonise space, the context of Stross’s estimate)

In other words, there is no reason to think a billion people would be too few to sustain a technological economy. But what would a world of a billion people look like?

It’s foolish to try to say much about life hundreds of years from now. What could a contemporary of Shakespeare have to say about the London of today? But we do know that London and other cities existed long before Shakespeare and seem likely to continue far into the future (if we can get there). And many of the services cities have always provided will be needed as long as people are people. So, it might be worth imagining how a world population of one billion might be distributed across cities, towns and rural areas.

Australia, with 5 per cent of the world’s land mass and a current population of twenty-five million, provides a convenient illustration. A billion people would populate forty Australias with twice Australia’s current population density. But around half of Australia is desert or semi-arid (estimates range from 18 to 70 per cent, depending on the classification) and not many people live there. So, the population density of a billion-person world would look pretty much like that of urban and regional Australia today.

Opinions in Australia (as elsewhere in the world) are pretty sharply divided as to whether a bigger population would be a good thing, but it’s unusual for anyone to suggest we are spread too thinly. On the contrary, congestion, sprawl and the conflict between environmental preservation and housing are seen as the price to be paid for a larger population.

A billion-person world could not support mega-cities with the current populations of Tokyo and Delhi. But it could easily include a city the size of London, New York, Rio or Seoul (around ten million each) on every continent, and dozens the size of Sydney, Barcelona, Montreal, Nairobi, Santiago or Singapore (around five million each). Such a collection of cities would meet the needs of even the most avid lovers of urban life in its various forms. Meanwhile, there would be plenty of space for those who prefer the county.

With only a billion people we wouldn’t need all the space in the world. The project of rewilding half the world, now a utopian dream, could be fulfilled while leaving more than enough room for farming and forestry, as well as whatever rural arcadias followers of the simple life could imagine and implement.

The final part of After the Spike looks at policies that might significantly increase fertility and finds, unsurprisingly, that there aren’t any or, at least, none that will make much difference. The negative example of South Korea shows that a combination of patriarchal social attitudes and large-scale female labour force participation can produce very low fertility. And the peculiar circumstances of Israel push rates just above replacement. But otherwise, the NRR in developed countries lies between 0.75 and 0.9, regardless of family policies.

It makes sense to adopt policies that make it easier to raise a family. But most of those policies also make other options easier, with the result that family size doesn’t grow. Having written an entire book on opportunity cost, I am happy to see Spears and Geruso using this concept to make this point.

The central reason for declining birthrates is that, as potential parents, most of us have decided that putting a lot of effort into raising one or two children is better than spreading those efforts over three, four or more. What is true for individual families is true for the world as a whole. Until we have the resources to properly feed and educate all our children, we shouldn’t worry that we are having too few

{ 90 comments }

Anonymous 08.18.25 at 4:13 am

I was Googling for old articles about the oil production plateau and peak oil discussion. Sent me to your articles in 2006 and 2007 era, talking about a definite decline from ~72 MM bopd starting in a decade (we are at ~82 now, and at lower real prices than in 2007). Also, your 2015 peak oil prediction, which failed also.

Not (just) a callout. But wondered if you revisited some of your peak oil ideas, and or discussed the shale boom. (I tried Googling for it, but didn’t find it.) Can you link, if you have a good retrospective on your peak oil journey?

MisterMr 08.18.25 at 5:31 am

“Until we have the resources to properly feed and educate all our children, we shouldn’t worry that we are having too few”

how much education per child is enough? Middle school, high school or PhD?

The rising levels of expected education are part of the problem (assuming it is a problem) of lower fertility.

JoeinCO 08.18.25 at 7:51 am

We take the demographer’s projections as somehow reasonable. But beyond population “inertia” from existing demographic bulges they are based on very tenuous assumptions. I predict that the so-called “demographic transition” can just as easily be reversed. Here’s a scenario where that could happen. Recall that one big driver of economic growth has been the move toward two-earner households with greater participation of women in the formal economy (and in higher-productivity roles than prior). This is basically capital replacing labor in the household. With AI replacing labor in in the knowledge sector (and soon, robots in the service sector and trades) it will free up labor for the household. In a utopia the benefits of AI would be well-distributed, but I am not an optimist. So let’s say that people are made poorer (relative to the tech-bro overlords) but either way, their labor will be more valuable in the household than in the workforce. This completely alters the “decision” that you refer to when discussing declining birth rates. No daycare. No real economic need for higher degrees. And with stay-at-home parents kids become, as a religious colleagues used to say, “cheaper by the dozen”. (he and his wife had 8, IIRC).

Tm 08.18.25 at 1:10 pm

Your review of this pro-natalist fear-mongering seems uncharacteristically mild. The book paints a picture of “depopulation” already in the very first sentence:

“Humanity is on a path to depopulation. You, your parents, their parents— any ancestors whose names you know— have been part of a growing population. And now a reversal is on the horizon. Birth rates have been falling everywhere around the world. Soon, the global population will begin to shrink. When it does, it will not spontaneously halt at some smaller, stable size. It will not fall to 6 billion or 4 billion or 2 billion and hold there. Unless birth rates then rise and permanently remain higher, each generation will be smaller than the last. That is depopulation.”

Of course it is trivially true that if population begins to shrink and then doesn’t stop shrinking, it will continue shrinking! But “depopulation” to levels under 1 billion is a scenario many centuries in the future. Absent a major disaster event like a nuclear war or a global famine (both of which are not unlikely at all but for some reason they are not the kind of problems the pronatalist propagandists are concerned about), there will be no “depopulation” during the lifetimes of any of us. How fertility rates will develop during the 22nd century cannot be reasonably forecast. That should be the end of this discussion, and it should have been the end of this book project at least in its current form if the publisher had a meaningful quality control in place.

Tm 08.18.25 at 1:19 pm

PS I’m genuinely puzzled what the authors’ motivation is for writing this kind of book. They believe that depopulation is inevitable and it’s a big problem but will only affect later generations centuries from now. They also seems to believe that nothing can be done about it. What’s the point then? How about concentrating on addressing the existential problems that we have right now and that we actually know what to do about?

somebody who remembers "we" can do what we want 08.18.25 at 4:32 pm

I suggest that, of course, “we” have enough resources to feed and educate every child on the planet to any extent “we” desire. It is the system of global capital that “we” set up that ensures that this does not happen and cannot happen. “We” have no interest in feeding every child or educating them. There is no desire to do so and it will not occur until there is a desire to do so. What “we” want is for near-infinite resources to be used to create pieces of paper held in a box in Panama or the Seychelles. “We” could simply instead expend those resources on feeding and educating children, but will not. I submit that a world that prioritized those two values would also be a world that treated families and children extremely differently, and which would, in my view, have higher birthrates. Since I’m a doomer, I don’t think this world is possible and when AI takes over the medical industry it will simply kill around half of all children born due to ordering expectant mothers to take huge amounts of Brain Force Plus and Trumpvermectin and eat three rocks a day. Our global capitalist leaders think that you need to eat the AI glue pizza and the rocks or else they won’t give you a job.

engels 08.18.25 at 5:43 pm

This probably applies to food consumption too (given this is seemingly about relatively well-off westerners…)

engels 08.18.25 at 6:10 pm

Ie. “properly feed your kids”

In 1975: oven-cooked fishfingers and an apple

In 2025: deliverood MegaMac with cheesy bacon fries and three cokes (£22.99 + tips)

Harry 08.18.25 at 6:44 pm

Completely naively, the absolute numbers don’t worry me — a billion sounds ample. But, also naively: is there a reason to worry not about the number of people that are left at the end of the decline, but what happens during the decline, especially if it is not steady? (ever increasing median and mean ages, economic and therefore political effects of sudden changes in particular places, etc?).

oldster 08.18.25 at 6:52 pm

“Having written an entire book on opportunity cost….”

Sure, but consider what you could have done with that same amount of time and effort.

Tm 08.18.25 at 7:03 pm

My first comment apparently got lost?

Tm 08.18.25 at 7:06 pm

“I suggest that, of course, “we” have enough resources to feed and educate every child“

In principle yes, but this won’t remain the case if population continues increasing and the climate crisis starts affecting agricultural productivity, which it will soon, if it doesn’t already.

Chetan Murthy 08.18.25 at 7:16 pm

Harry @ 8: “is there a reason to worry not about the number of people that are left at the end of the decline, but what happens during the decline, especially if it is not steady?”

It depends: do you think that we should or should not -eventually- stop growing the Earth’s human population? If you think we should stop (again: “at some point”) then I think you would want that point to be sooner rather than later, b/c the bigger the population is, the more trouble it will be to deal with all those effects you adduce. And obviously, if you think that a larger population will put more stress on the planet, then those effects would be compounded by the stress on the planet, but you don’t need to believe in that, to believe that -eventual- population stasis/decline will be worse than -nearer-term- population stasis/decline.

What I’m saying is, if our reason for not wanting decline -today- is that we’re merely kicking the can down the road …. that’s not very responsible. BTW, a similar argument is made [which I buy] for some forms of geoengineering to combat climate change. If we decide to loft sulfate aerosols into the stratosphere in order to reduce insolation, but we don’t reduce CO2 production, then we’re -stuck-: we cannot -ever- stop that geoengineering, b/c we’ll get a -massive- boomerang as the sulfates (eventually) fall out of the stratosphere and al that CO2 we kept on pumping into the atmosphere gets to work with all that renewed sunshine/heat.

Harry 08.18.25 at 9:30 pm

Obviously — well obviously to me, maybe I’m wrong — there’s SOME level of population that is unsustainable! I’m not arguing against decline, just want an understanding of the downsides of the actual process, which presumably we need in order to manage it well.

dk 08.19.25 at 3:47 am

tm@5

John Q 08.19.25 at 5:46 am

@Harry “what happens during the decline, especially if it is not steady?”

John Q 08.19.25 at 5:54 am

@1 Replied on my blog

Alex SL 08.19.25 at 8:31 am

The idea that number of children per woman would remain constant over centuries while population dwindles to zero is so silly as not even require serious examination. Everything changes and evolves in that time, partly in response to the population contraction.

In the meantime, it is much too early to worry about any of this. Objectively, the most likely scenario for the next two centuries is a collapse of industrial society, as the effects of climate change and resource overuse overwhelm the capability of nation after nation to respond and adapt, with hundreds of millions of climate refugees setting off chains of political disintegration. The main wrench that has so far been thrown into that prognosis is that society may collapse much sooner than that if we collectively keep electing the Donald Trumps and Boris Johnsons of this world, because with sociopathic kakistocrats in charge we won’t even get what responses and adaptation would otherwise be feasible to stave the worst consequences off for a bit. And the more climate refugees, the more xenophobic reaction, the more kakistocracy, the more climate refugees. It is a positive feedback loop, and not clear to me how to escape it.

Point is, regardless of when exactly it happens, it is anybody’s guess what NRR will be once the current complex societies have been replaced with warlords ruling over the next dark age. On the one hand, some contraceptive technologies may not be lost, and it is perhaps difficult to predict what effects microplastics, hormone overuse, forever chemicals, and whatever horrors of chemistry and radiation happen during collapse have on fertility for decades or centuries even after the phase of collapse has played out. On the other hand, it would perhaps be foolishly optimistic to assume that the next dark age will be characterised by women’s right to choose whether to remain unmarried or not have children, so NRR may at some point revert to what it was in 600 CE.

JoeinCO,

Generative AI is certainly destroying jobs to the degree that customers do not care about quality, e.g., when artists are losing commissions for illustrating advertisements because the CEO is satisfied with generated slop art. But if mechanical robots that are autonomous and flexible enough to replace a human in more than repetitive assembly tasks can ever be made more economical than just paying a human the minimum wage, I will eat my hat. The requirement is a level of complexity and intricacy that is fundamentally impossible to replicate with cogs and cables, and any successful replication with other designs would be extremely complex and intricate and thus expensive to build and maintain. A disembodied arm screwing one screw in every three seconds: yes; Data from Star Trek as a child care worker: not going to happen. Also, of course, an inhuman suggestion that may yet trigger the Butlerian Jihad.

Even for purely computational work, it currently isn’t clear that LLMs can be run at profit, as a business. Just the other day, Altman apparently claimed in an interview that they were now profitable on inference, meaning: if you don’t count the training, data curation, etc. This is very funny. I too can run a profitable business if I don’t have to count creating the products I am selling! And then his colleague next to him squirmed and clarified that they were still only nearly profitable even on inference alone. They are just setting money on fire and hoping that they will somehow magically become profitable one day. Now look again at the title of the OP and consider what providing a service at the cost of constantly setting money on fire means for “AI replacing labor in the knowledge sector”. Will it, once people have to pay subscription fees that cover what it actually costs to provide the service? Colleagues who are using LLMs for assisted coding balk at the idea of a few hundred dollars per year, so, no, I don’t see that happening.

Conversely, if everybody hypothetically became unemployed because AI and robots are running everything, your question of whether that gives people more time to raise children would not even make the top twenty most urgent considerations. It would completely collapse the entire capitalist system, leading to either a communist revolution or to the future depicted in much of the cyberpunk genre, i.e., the vast majority of humanity squabbling and back-stabbing each other in abject poverty while a few trillionaires monopolise wealth and resources and throw crumbs to the armed goons who keep order. It is anybody’s guess how many children people will have under either scenario, but also irrelevant, because we have arrived in the realm of completely fantastical speculation.

Laban 08.19.25 at 10:51 am

United Nations 2024 projections for Africa don’t show a declining population – far from it:

https://population.un.org/wpp/graphs?loc=903&type=Probabilistic%20Projections&category=Population&subcategory=1_Total%20Population

Median projection for 2100 is 3.5 billion from 1.5 billion in 2020.

MisterMr 08.19.25 at 10:55 am

@engels 8

You are speaking of the costs of rising a kid, but I’m speaking of age:

image a couple that marries at 25 (presumably because they have already more or less steady jobs) and their parents did the same so are now between 50 and 60; this couple is going to have much more kids than a couple that finds job stability at 35 and whose parents are 70-80 and therefore struggle to help with the kids, and if the couple is in their 40s the problem is even worse.

In modern rich developed countries, the level of education increased a lot, which is a good thing, but maybe it is also a form or rat race where you need education to get a decent job but other people are also inceasing their own education etc.; this is going to push up the age when couples stabilize and the number of kids they will pop out.

As I said in another thread, I don’t think that declining population is an actual problem, maybe it will be 100 years from now but now it isn’t.

However, to the degree that it is a problem, it is due to the fact that couples don’t want kids; why do couples don’t want kids?

There are two explanations:

One is that naturally people don’t want kids but just popped out they accidentally because old contraceptives sucked. I think this explanation is unrealistic.

The second is that people do not feel secure enough to have kids; how can this be if people today are richer than in the past?

The main problem is time, since now most women work so they have more problems to care for the kids; this could be solved by reducing the workweek for both parents so they have more free time.

But also the problem is that people do not just want to survive, they want lives that are acceptable socially among their peers, good jobs etc., ands it became IMHO more difficult to get that in the modern world, in a large part because of a rat-race effect between workers.

This is also a problem of “capitalism”, even though people when speak of “capitalism” think only of the effects created by capitalists: ultimately is still the problem of unemployment/underempoloyment and of the reserve army of labour: if youi don’t want to fall below of a certain standard you need to reach certain standards, and the standards become higer and higer.

Anonymous 08.19.25 at 11:29 am

#17 (John)

Where, please?

I looked on the regular blog and substack, but just not finding the reply. I also sometimes can’t find something on the shelf at the store, when it is there!

Michael Cain 08.19.25 at 1:45 pm

John Q @ 16: For #2, with ongoing medical progress at keeping bodies going, isn’t there likely to be a steadily increasing ratio of dependent elderly? Not just dependent in the sense of retired, but in the sense of requiring assistance with the activities of daily living.

Laban 08.19.25 at 2:46 pm

“Concern about the possibility of a declining population emerged when the number of births peaked in 2012. “

If births in Europe and Asia are falling and those in Africa are rising fast, our future is going to be a lot more African that depicted in sci-fi literature and film. As someone said, the future belongs to those who show up for it. Demography is a game of last man standing.

It’s received liberal wisdom that the longer a girl stays in full time education, the fewer children she has. This isn’t great news because if you accept that years of education is a rough proxy for intelligence, it’s implying that the brightest girls will have fewest kids. Wouldn’t be a worry if intelligence was randomly generated, but all the evidence is that it’s to a large extent heritable. Maybe Idiocracy IS our future.

(Stein’s Law was expressed pithily well before Stein’s birth by an old German proverb – “Bäume wachsen nicht in den Himmel” or “the trees don’t grow up to the sky”. )

Tm 08.19.25 at 3:51 pm

Laban 19, UN projections have been criticized for being on the high side. But Africa is by current trends the only continent that will significantly grow over the next decades.

I’m always wondering when I see these projections how they imagine the food to come from to feed more than twice the current population of Africa. Cutting down the remaining rainforests won’t “help” much because the tropical soil isn’t very suitable for farming.

Tm 08.19.25 at 3:54 pm

Thanks for the link btw.

Laban 08.19.25 at 4:44 pm

TM – “Cutting down the remaining rainforests won’t “help” much because the tropical soil isn’t very suitable for farming”

Agreed, and soils/fertility (of plants)/climate are a whole fascinating topic on their own. What happened to the once-green Sahara? Interestingly geological stability (no earthquakes/eruptions) is very bad for long-term fertility. Northern Australia has been geologically stable for a long time, no glaciations, the soil has been weathered and lost most of its nutrients.

“Australian dryland soils are acidic and nutrient-depleted, and have unique microbial communities compared with other drylands”

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6373843/

MisterMr 08.19.25 at 4:50 pm

@Laban 22

I don’t think years of schooling are inheritable, unless by inheritable you mean in the same sense that parents’ money is inheritable.

engels 08.19.25 at 6:11 pm

Last try (with minimal jokes).

1 People are having fewer children. 2 People are acquiring more credentials. 3 People are getting fatter.

The post claims parental resource constraints rationalise 1. MrMr points out 2 contributes to this. I’m just pointing out that 3 does too.

And then noting that 2 and 3 counteract the effects of 1 to an extent. An obese and hypereducated population is more productive (in a knowledge economy) but also more demanding in terms of environmental resources (most obviously space).

Fake Dave 08.19.25 at 8:10 pm

Why engage with this sort of innumerate pop demography drivel at all? It’s bad enough when wonks are just p-hacking and drawing lines to infinity to tell each other what kind of jeans “Gen Alpha” will be buying, but this is Fate of the World shit and there’s no excuse for it. Every year we get these puffed up Big Idea books structured around some cover-ready image of a radical breakdown, transformation, or tipping point and they tend to age terribly. At best, this going to be another rote installment in the Culture of Narcissism genre where the retiring Me Generation are sold an image of the world literally ending with them. At worst, it’s grist for the mill of fascism as the Clash of Civilization crowd conjures up a demographic apocalypse threatening our identity, way of life, and the future of “our” children. It’s not a coincidence that these same people tend to reject the obvious solution of immigration from higher birthrate countries as a cure worse than the disease.

Too many people are using this natalist handwringing as a Trojan horse for speculation about a different kind of “demographic apocalypse” that is much less palatable to the mainstream. We need to be calling them out for their false premise of endless decline and no more babies to care for the elderly, not validating their belief in the necessity of rightwing social engineering to prevent a “great replacement” and the Fall of (Western) Civilization.

engels 08.19.25 at 8:16 pm

You are speaking of the costs of rising a kid, but I’m speaking of age:

Point taken. In each case (education, food) there may be a direct effect of rising consumption norms on family formation and a second-order effect on procreation choices driven by parental assumptions about acceptable per child spending.

Speculation about the direct effects of rising obesity is probably best left out of this discussion.

Laban 08.19.25 at 8:26 pm

MrMr 20

The second is that people do not feel secure enough to have kids; how can this be if people today are richer than in the past?

I can only speak for the UK, but it is possible here to be richer and still worse off, because of insane property inflation (which isn’t included in inflation figures, because “property is an asset”). I bought my first house 40 years ago (10k) on a very low single wage, and where I now live 25 years ago (120k), on a healthy single wage. So my wife could take 8 years out to raise four kids, because we didn’t need her wage for the mortgage. And there were enough mothers in the same position to still have a social life, albeit with added little ones.

For most people now that’s impossible – you NEED two wages even for a three bed semi (around £300k where I live). Median UK wages are around £36k. So if you want babies you’re dropping them at nursery at 8 am and maybe picking them up at 5.30. Nurseries aren’t cheap, and you may have student loans to repay – another 9% on your taxable income. It’s incredibly stressful as my wife’s colleagues will testify.

engels 08.19.25 at 11:54 pm

MegaMac s/b Monster Mac

https://hackthemenu.com/mcdonalds/secret-menu/monster-mac/

JBW 08.20.25 at 2:21 pm

I think it’s possible to agree that worries about the global population getting too low to support innovation are silly without completely dismissing concerns about population decline. Like some other commenters on here, I don’t think all the causes of falling birthrates are benign, especially in countries where the birth rate is very low, notably South Korea, Japan, Italy, Spain. High cost of housing, intensive parenting with high stress and high competition, increasing credentialization delaying beginning a family, emphasis on professional achievement over family, friction over changing roles for women, fewer relatives to support families, and, especially among the youngest cohort, the dominance of online life over real socialization leading to less coupling are surely among them in different proportions. Taken together, they reflect societies in which few or no spheres of life are insulated from market pressures. Certainly this is all very apparent in my social group (older millennial women professionals in the US) and our fertility choices.

I also think, as Harry suggests above, that it’s not unreasonable for societies with a fertility approaching or below 1 to consider how to slow down population decline and how to manage it successfully. Whatever the process looks like for the globe as a whole, it seems likely that it will entail some degree of upheaval in the places that experience it most dramatically and earliest, like South Korea. I’d be very interested in a discussion of what this might look like–I think one can be had without conceding to wild pro-natalist fantasies about the global population.

John Q 08.20.25 at 8:45 pm

Anon @21 Reply is here. https://johnquiggin.com/2007/07/26/plateau-oil/comment-page-1/#comment-266015

Bob 08.20.25 at 9:17 pm

John, I have a question about your example of a self-suffcient US economy. I don’t think this changes your conclusions, but still, I was a bit confused by your reasoning. The US, with a population of 400 million, produces a certain level of GDP, 20% of which is traded with other countries for goods not produced in the US. If the US were cut off from all trade, demand for the existing mix of goods and services that make up US GDP would be 20% less. This would mean that 20% of existing US labour and resources, now idle, could be repurposed to provide the goods and services that the US was previously importing. You would only need MORE people to the extent that the imported goods were more labour intensive, on average, the prior mix of US goods and services. This is, in fact, probably the case. So, yes, you would probably need more people, but not for the reason that you gave, and probably not as many. No? What am I missing?

J-D 08.21.25 at 1:17 am

Why not ask ‘Why do people want children?’

There are multiple reasons why people individually choose to raise** children and also multiple reasons why people individually choose not to raise children. On a large scale, people have often chosen to raise more children when it’s been economically advantageous. From a purely economic point of view, choosing to raise children is something of a gamble, because it’s possible to invest significant economic resources in them and then have them die before they provide any economic return. However, in a pre-modern society where the utility of additional labour was not constrained by the limitation of other resources (such as, in an agricultural society, shortage of arable land), if you could raise a son to adulthood he would, in purely economic terms, more than pay for the cost of raising him. In a pre-modern society a child could start providing at least some economically valuable labour well before adolescence. In colonial North America, where there was an abundance of arable land, a widow with children was an economically attractive marriage prospect because a man who married her could immediately benefit economically from the labour of those children.

Obviously it’s different now.

** It’s not just about whether people choose to have children. In many human societies a decision not to raise a newborn has been openly acceptable. In many more although it has not been openly acceptable, it has been tacitly accepted although nominally denied or disguised.

F. Foundling 08.21.25 at 1:51 am

‘Until we have the resources to properly feed and educate all our children, we shouldn’t worry that we are having too few’

Ahem, we do have the resources? The problem is that we fail to distribute these resources adequately and instead choose to give them to our billionaires, CEOs, financiers and corporations, who then use them for all sorts of useless or directly harmful purposes, because enormous economic inequality and plutocracy, because capitalism. Not to mention states using them for weapons and war, because imperialism. This is not scarcity, these are choices we keep making.

As for the population decreasing – if the overall trend goes on indefinitely regardless of family policy, the solution is obvious: having and raising a certain number of children will just have to be made a citizen’s legal obligation, like paying taxes and conscription. (Sorry, but if the survival of modern civilisation and of humanity in general are at stake, that will have to take precedence over individual freedom and bodily autonomy.) Naturally, this will also presuppose that the State finances, supplies and actively assists the process instead of treating it primarily as the citizens’ private business, as it does now.

J-D 08.21.25 at 3:00 am

That’s a weird way of putting it. I have no idea whether it’s ‘received liberal wisdom’–I don’t know how anybody could tell what ‘received liberal wisdom is’. When I see an expression like ‘received liberal wisdom’, it makes me feel that the person who uses it is trying to have a snide dig at somebody as a way of affirming their own superiority.

Anyway, even if there is such a thing as ‘received liberal wisdom’, isn’t it more relevant whether the statement is true than whether it is received liberal wisdom? When somebody writes ‘It’s received liberal wisdom that X’ it seems more likely than not that they don’t agree with the statement X, and in this case if somebody doesn’t agree that the longer a girl stays in full time education the fewer children she has, doesn’t that make an important difference?

But I don’t accept that years of education is a rough proxy for intelligence and there’s no good reason why I should. If that supposition is, as I take it to be, a load of rubbish, then there’s no basis for the concern after all.

The evidence is sketchy or worse. It’s hopeless even trying to measure the heritability of intelligence without a much clearer idea of what intelligence is than anybody has so far.

engels 08.21.25 at 11:50 am

This too. I feel this series of posts has tended to conflate individual and collective decision-making in an unhelpful way. That “we” (affluent educated Westerners) don’t have the resources to feed and educate more children (feed them sushi for breakfast and send them Harvard) is different problem from the world as a whole not being able to (albeit the two problems are connected but in a more antagonistic way than the posts let on).

MisterMr 08.21.25 at 12:05 pm

@J-D 36

“Why not ask ‘Why do people want children?’”

Because my assumption is that people instinctively want children, the same way I expect most people to instinctively want sex.

The idea that humans generally do not want children seems strange to me.

Because fo a certain period women were confined in the role of childcare and other housework, a large literature spawned about women who do not necessarily want children, and thus there is this certain idea that children are a sort of imposition.

While I’m sure this is the case for some people, it seems strange to me to not assume that most people want children: human kids need a lot of care and if we weren’t naturally inclined to care for kids we would probably not have survived until now.

So if people do actually instinctively want children, but don’t have them, there is the question of why.

Not really apropos of this, two links:

An historian blogs about family formation (Umarriager and kids) in the ancient mediterranean

A book that I read recently by an anthropologist/primatologists that discusses the peculiarity of human family formation and how differences with other primates might be part of the reasons that our intelligece evolved. Mothers and Others: The Evolutionary Origins of Mutual Understanding (spoiler: because humans need more alloparenting, that is adults other than the mother who care for the child).

Alex SL 08.21.25 at 9:13 pm

MisterMr,

My hunch is that while most people instinctively want children, the combination of that only being ‘most’ and most of those most being happy with one or two children results in any society that gives people the choice having fewer than two children per woman on average. I don’t know this for certain, admittedly. Maybe it is a question of support and incentives. But it is striking to me that both historically and geographically, societies with many children per woman generally were and are characterised by some combination of low education, limited access to contraceptives, poverty, and oppressive sexism, all factors that restrict choice to varying degrees.

ETB 08.21.25 at 9:33 pm

I would say if you’re going to talk about resources, then perhaps you should talk about y’know actual resources (and not abstractions, like “wealth”). E,g,, the total sustainable energy production is estimated at around 13,000 TWh. If you divide that by the approximate population (8.2 billion or so), then (if my calculator doesn’t fail me) I think you get a value of ca. 5.7 GJ/person (roughly that of central Africa, or 1/20th of China). Is it possible that people eating

avocado on toastsushi is not the only problem here?To try and forestall a certain commentator’s

propensity towards hysterically declaring any mild contradiction an evil conspiracy by neoliberal stoogesreasonable disagreement, I will say that this is not me saying wealth inequality isn’t a problem (clearly it is, though to my mind a far more significant point is the need to disrupt the ability of capital to leverage wealth for self-propagation), nor is it that there is no room for improvement (I’d recommend reading Hickel for some interesting arguments regarding decent living standards https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wdp.2024.100612), it is only to very tentatively suggest that redistribution of the current system alone won’t solve the issue (unless you either accept the situation as being untenable, decrease the population dramatically, or increase sustainable resource production by at least an order of magnitude).Of course reasonable people may disagree and all that jazz, but it’d be nice to see some data backing it up…

ETB 08.21.25 at 10:27 pm

I mean, intuitively humans probably do generally want children (species with no interest in reproduction don’t tend to be around for self-evident reasons). But how many is most, and how many children most would want, are perhaps less self-evident?

It might (or might not!) be that some find their tolerance for the whole having a kid business varies a bit (for some people some of the time it can be a bit inconvenient, unpleasant, and even have a whole host of minor-to-significant temporary-to-permenant heath side effects). On the other hand, I’ve no idea how you’d go about disentangling the emotional aspect from the reproductive labour part…

John Q 08.22.25 at 4:20 am

“Until we have the resources to properly feed and educate all our children, we shouldn’t worry that we are having too few”

I’ll correct that to “Until we have mobilised the resources …”

There’s certainly enough to give a high-quality diet to everyone, if it were properly allocated, but it would be impossible if population growth hadn’t already slowed. https://aeon.co/essays/we-can-end-world-poverty-without-destroying-the-planet

Education is a lot harder. To give everyone an education sufficient to participat a modern economy (that is, high school plus a trade qualification or degree) would require many millions more teachers than we have, plus the people to teach the teachers etc. That’s really impossible if each cohort is larger than the one that went before.

“feed them sushi for breakfast and send them Harvard”

Engels, I’m regularly struck by your focus on the very top strata of the UK/US post-school education system, perhaps because Australia has nothing comparable.. Harvard has about 5000 undergraduates a staff-student ratio of something like 5 to 1. It’s relevant to the reproduction of the US ruling elite, but not to the problems I’m talking about.

John Q 08.22.25 at 4:22 am

Bob @35. You’re quite right, but I wanted to give an upper bound estimate, to show that a billion people would be plenty even on very generous assumptions.

Tm 08.22.25 at 10:01 am

MisterMr 40: “Because my assumption is that people instinctively want children”

I think that’s wrong. My assumption is that the sex drive is instinct (although it still varies individually and it can be suppressed) but wanting children has nothing to do with wanting sex. Only without birth control there is no way to have sex and not produce children. Now we have reliable birth control and it turns out that people have very different preferences regading having children or not.

There are certainly people who absolutely want children and deeply regret if they can’t have any (and are often willing to go through insane procedures to make them happen). But many other people do not regret not having children. In our society there is still a strong pressure to conform to a happy family with two children ideal even though it’s becoming anachronistic. I’m pretty sure that it is social pressure more than anything instinctive that influences people’s wish for children. I observe that people who don’t have children often feel the need to justify their choice; nobody feels the need to justify having children. Not to mention that the fascists now ruling the US used shaming childless women as a campaign tactic. I thought it would backfire but apparently not.

I also observe with sadness that many people who have children are stressed and overextended and unhappy (although most wouldn’t dare admit that having children was maybe a bad choice), and also many children growing up in today’s society are unhappy. I don’t dispute that having children is also for many parents a source of great joy and I love children myself very much but my impression is that our society with its nuclear family structure, which in my view is not species-appropriate, and unrealistic parenting norms and expectations is really not a healthy environment for raising children. Children should be around other children most of the time, they shuld be free of adult oversight much of the time, and they should have many more adult attachment figures than just their parents. In our society it is next to impossible to provide children a child-appropriate environment to grow up in. I think this is one of the biggest problems of our time and I don’t know what can be done about it.

Tm 08.22.25 at 10:04 am

Seconding ETB 42.

engels 08.22.25 at 10:26 am

struck by your focus on the very top strata… Harvard has about 5000 undergraduates

Ok here’s a wider angle (for UK):

https://thetab.com/2024/09/23/its-official-these-30-universities-are-crawling-with-the-most-private-school-students-in-2024

A better definition might be Annette Lareau’s “concerted cultivators,” which encompasses most of the struggles mentioned by JBW above, with the exception of housing.

https://content.ucpress.edu/chapters/9987001.ch01.pdf

engels 08.22.25 at 1:12 pm

it is only to very tentatively suggest that redistribution of the current system alone won’t solve the issue

“If we broke up the banks, would that solve climate change?”

https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/2016-election/clinton-ramps-single-issue-candidate-attack-sanders-n518261

ETB 08.22.25 at 2:50 pm

When someone quotes me, I tend to assume that the text which follows will in some way be a response to me – yet, in a delightful subversion of expectations, here that isn’t the case. I eagerly look forward to more links to irrelevant yet doubtless fascinating news articles from a decade ago to be whimisically directed my way!

(still not data, of course, but – after all – who am I to suggest it may be important to consider material needs…)

ETB 08.22.25 at 3:06 pm

Since we are linking things for entertainment purposes, here’s one:

https://www.sanders.senate.gov/op-eds/climate-change-is-a-threat-to-the-planet-we-must-address-it/

ETB 08.22.25 at 4:12 pm

(posting again, as not sure if the previous comment submitted correctly)

I must admit, generally when someone quotes me I tend to assume text will immediately follows will, in some way, be a response to me – yet here that expectation was delightfully subverted! I look forward to more no-doubt fascinating yet unrelated links being whimsically sent my way in future.

(this still isn’t data, of course, but whomst among us would be interested in material needs?)

engels 08.22.25 at 5:26 pm

Redistribution alone won’t solve climate change but it will solve undereducation, which was the claim made (and overeducation, and ditto for food).

ETB 08.23.25 at 8:17 am

A rather important word in my post was “sustainability” (particularly given that we are talking about generations here). If redistribution relies on resources with decreasing availability due to (a) being finite) and (b) downstream impact (e.g. available arable land shrinking due to climate impact) then the effect on population would seem rather easy to predict (“if something can’t go on forever, it will stop”). Again, redistribution is a good thing, but alone it isn’t going to solve the problem of resource availability (at best it will postpone it) which means it isn’t going to solve other problems.

Laban 08.23.25 at 6:11 pm

JD 38

“without a much clearer idea of what intelligence is than anybody has so far.”

And yet people for whom it can literally mean life or death find ways of measuring it.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Raven%27s_Progressive_Matrices#Uses

Because of their independence of language and reading and writing skills, and the simplicity of their use and interpretation, they quickly found widespread practical application. For example, all entrants to the British armed forces from 1942 onwards took a twenty-minute version of the RSPM, and potential officers took a specially adapted version as part of British War Office Selection Boards. The routine administration of what became the Standard Progressive Matrices to all entrants (conscripts) to many military services throughout the world (including the Soviet Union) continued at least until the present century.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Armed_Services_Vocational_Aptitude_Battery

“Applicants in Category V (bottom 10%) are legally ineligible for enlistment.”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Project_100,000

…a controversial 1960s program by the United States Department of Defense (DoD) to recruit soldiers who would previously have been below military mental or medical standards. According to Hamilton Gregory, author of the book McNamara’s Folly: The Use of Low-IQ Troops in the Vietnam War, inductees of the project died at three times the rate of other Americans serving in Vietnam and, following their service, had lower incomes and higher rates of divorce than their non-veteran counterparts.

engels 08.23.25 at 11:52 pm

What’s that old joke about military intelligence being a contradiction in terms?

John Q 08.24.25 at 5:20 am

Engels @53 “overeducation”

Do you really think that, on average, people in rich countries are getting too much education?

You’re not one of those “my old dad left school at 15 and he did fine” types, are you?

@48, yes, the top strata reproduce the ruling class, and only educate a small proportion of the population. That’s what I said.

J-D 08.24.25 at 8:12 am

Nope.

Your citations tell me about tests being widely accepted for use by armed forces. But the history of medicine tells me there are multiple examples of techniques that were widely accepted for centuries by people who devoutly believed that they worked in cases where it was a question of life or death and which people had theoretical models to support their beliefs but which techniques a subsequent better understanding has revealed to be useless or, in some cases, actually harmful. The fact that armed services keep using these tests does not demonstrate that they are a reliable measure of anything real.

engels 08.24.25 at 9:44 am

No, on average I think they’re undereducated but using markets to allocate school or university places is a really terrible approach that produces misallocations in both directions.

John Q 08.24.25 at 10:50 am

Engels @59. So, even to get enough education in rich countries we need more teachers and supporting resources as well as better allocation. And that’s massively more so when it comes to poor countries.

Laban 08.24.25 at 11:14 am

“Do you really think that, on average, people in rich countries are getting too much education?”

They’re certainly getting too much time at university, and too much debt (UK correspondent here). As for education, I couldn’t say.

Nothing like going into the world of work with an extra 8 or 9% tax rate, and rents for median earners at 36% of income. God knows what percentage poorer people are paying.

https://www.theguardian.com/money/2025/aug/18/tenants-in-england-spending-unaffordable-36-of-income-on-rent-shows-survey

engels 08.24.25 at 11:31 am

Yes: we will need to redistribute resources from socially useless activities to education, as well redistributing education towards those who will benefit from those who can pay.

Tm 08.24.25 at 7:49 pm

There are 1.6 billion cars in operation.

These cars are responsible for our planet-destroying dependency on oil and our democracy-destroying dependency on petroleum dictatorships. Their 1.6 billion owners and their families are not the top 1%, not even the top 10%, they represent maybe one third to half of the world population, and in Europe and North America the majority by far of the population have cars.

This majority of car owners is the source of the power of the fossil fuel oligarchy, the reason why every baby step for climate action provokes a fierce backlash, the deeper reason for the rise of fascism.

It is true and proper to point out that the oligarchs with their yachts and jets and spaceships use more resources each than thousands of ordinary people. We should oppose them by all means available. But even if a decent government had the courage to tax the yachts away, we’d still have to deal with the 1.6 billion cars burning record amounts of oil and emitting record amounts of greenhouse gases every day. And as long as 1.6 billion car owners want the fossil fuel economy to continue, there will not be a decent government with the courage to oppose the oligarchy, because most car owners don’t hate the oligarchs and their yachts, they admire them and even vote for them or their political lackeys. The rather hate the urban bicyclists and transit users.

That’s our dilemma, the dilemma of the left, and of all the radicals who’d like a livable planet, and nobody seems to know what to do about it, except to hope that the technological superiority of renewables and EVs, combined with declining fertility, will displace the fossils quickly enough on its own. Which is unlikely. But at the moment, any political solution is foreclosed by those 1.6 billion. This will only change if the number of people relying on oil driven cars starts declining substantially.

At least there are for the first time signs that fossil fuel use might peak, China’s have slightly declined in the first half of 2025.

Laban 08.25.25 at 9:54 am

Tm 63

While I agree with you (apart from “mum and dad driving to work = fascism”) I’ve been told for at least the last ten years that coal and oil are “yesterdays fuels”, and yet every year (bar covid) a new record is set for burning both.

https://www.iea.org/news/global-coal-demand-to-remain-on-a-plateau-in-2025-and-2026

https://www.iea.org/reports/oil-2025/executive-summary

Global oil demand is forecast to rise by 2.5 mb/d from 2024 to 2030, reaching a plateau around 105.5 mb/d by the end of the decade.

J-D 68

It’s probably a good thing that today’s med schools and best universities don’t share your views. I wouldn’t like a surgeon plucked randomly off the street operating on me.

Lots of people believed odd things in the past, but yet there are still a few people who believe odd things today (‘no such thing as intelligence’).

LFC 08.25.25 at 5:49 pm

Re certain comments upthread:

It might be an instructive exercise to go through the members of Trump’s inner circle of advisers and his cabinet appointments and see where they went to school. Here is a somewhat random sample:

Russell Vought (director of OMB): BA Wheaton College (in Illinois), JD George Washington Univ.

Pam Bondi (attorney general): BA Univ. of Florida, JD Stetson Univ.

Kash Patel (FBI director): BA Univ. of Richmond; University College London; JD Pace Univ.

Tulsi Gabbard (Director of Natl Intelligence): BS Hawaii Pacific Univ.

Stephen Miller: BA Duke Univ.

RFK Jr. (Secretary of HHS): BA Harvard; LSE; JD Univ. of Virginia; LLM Pace Univ.

Lori Chavez-DeRemer (Sec. of Labor): BBA California State Univ., Fresno

Scott Bessent (Sec. of Treasury): BA Yale

Steve Witkoff: Hofstra Univ. (BA, JD)

Marco Rubio (Sec. of State): BA Univ. of Florida, JD Univ. of Miami

A fairly diverse (pun intended) group of educational institutions there, I’d say. Among the undergraduate degrees, only three (RFK Jr., S. Bessent, and Stephen Miller) are from élite private universities.

JPL 08.26.25 at 7:11 am

LFC @65:

I just started this post from the bottom with your comment, and I believe this information is quite significant. I would also guess that its significance is not restricted to your very pertinent observation. So thank you, if you did that work.

I have been puzzling about crackpot and crankish thinking and how people develop it as their way of viewing the world, and what allows people to become that way, because it seems to me that what mainly characterizes this administration is that they are a collection of crackpots and cranks who are driven not so much by authoritarian ideologies, but by the desire to be hailed as right about everything and as saviours of the world (They should all put on hats like Trump’s most recent hat, but with the 1st person pronoun: “I have always been right about everything”.), when in fact they have been wrong about everything, and will continue to be wrong, with the way they are going about it. It might be interesting to compare these with Biden’s or Obama’s cabinet and advisors. But it’s an observation that deserves further thought and exploration. (I haven’t yet read the certain comments upthread.)

engels 08.26.25 at 12:15 pm

the sex drive is instinct (although it still varies individually and it can be suppressed) but wanting children has nothing to do with wanting sex… Now we have reliable birth control and it turns out that people have very different preferences regading having children or not.

They’re also having less sex.

https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2023-08-03/young-adults-less-sex-gen-z-millennials-generations-parents-grandparents

(Eating much more though as I said above, and watching a lot more pr0n.)

MisterMr 08.27.25 at 8:27 am

About instincts like sex drive and having children:

Once a woman is pregnant, there are hormonal changes in her that make her more child loving (an increase of oxytocin mostly), and this happens also to other people who live with the pregnant woman (though at a lower degree), so clearly there is an instict to rising children – once they are coming.

I’m not equally sure that there is an instinct to produce children different from the sex drive – it might be that “naturally” first people have an instinct to sex, and only when the child is coming oxytocin kicks in.

However, I have a 3 years old nephew and whenever I go around with the toddler all girls from 10yo onwards immediately start to play with the kid, much more so that male kids, so I’d say that there is an instinct for childcare, and that is sex dependent (obviously there can be big personal variations).

However even when something is instinctive, said instincts might or might not activate depending on the environment, like what happens to many animals who do not reproduce in captivity (even though they obviously have reproductive instincts in the wild).

So it is well possible that we have reproductive instincts (both sexual and childrising) that would work in a certain way, but don’t because of this or that social perception; the generation that is not having kids nor (apparently from Engels’ link) sex is also the generation where anxiety levels increased by +150% in girls and suicide rates by +50% in both sexes.

I recently read Haidt’s “anxious generation”, that is more than a bit on the moral panic side, however the numbers are indeed worring.

Has this something to do with changes in natality (that actually started one or two generations before)? Hell if I know, but it’s not impossible.

engels 08.27.25 at 10:02 am

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2025/aug/27/transport-emissions-gap-rich-poor-uk-forecast-to-widen

But let’s blame the plebs for getting each other pregnant and even clutches pearls owning cars…

LFC 08.27.25 at 12:40 pm

JPL @66

Thanks. My point was that even though, as certain comments upthread note, one function of elite universities is to reproduce the ruling class, when one looks at one slice of the ruling class in one sector of society (i.e. the fed govt in this case) one finds a range of educational pedigrees. My guess is that the Obama and Biden admins in these jobs might have a higher representation of elite degrees but I think my general point would stand, which is that there is more diversity of educational backgrounds than some commenters on blogs and other people assume is the case for the upper reaches of the political and economic spheres. At least in the abstract, that diversity of educational backgrounds is, I think, a good thing, even though in the case of the Trumpists it happens that most of them are, to use a technical term, bonkers. But that is generally not a result of where their degrees are from (Vought’s alma mater is an evangelical Christian college, so that might be an arguable instance of cause-and-effect but more likely his views were shaped before that).

The institution where there really is a high uniformity of pedigree is the current Sup Ct, where, as is often noted, all except one of the Justices’ law degrees are from Harvard or Yale w the exception being Amy Coney Barrett who went to Notre Dame for law school and was subsequently, after clerking for Scalia, a professor at Notre Dame law school.

engels 08.27.25 at 5:29 pm

LFC, I’m not sure if you’re referring to me at all but in any case I should clarify in this context I was using “Harvard” as a shorthand for expensive education. In Britain that means private (high) schools, home tutoring for Oxbridge entrance and £9k fees paid upfront, in US I guess expensive, usually private universities and higher degrees. And you do have to look at centrists for the most cliché cases of elite reproduction, that’s why they’re “the establishment” even though there’s nothing democratic about Trump or Farage’s millionaire sets.

engels 08.27.25 at 10:57 pm

Ie. most my criticisms on thread have been aimed roughly at “the 10%” (rather than the iconic 1%): private school/Russell Group grads on non-descript but nonetheless lucrative corporate gravy trains rather than Oxbridge pillocks, banksters, or what have you. You might call them JAEs (Just About Extracting).

LFC 08.28.25 at 12:33 am

engels @71

Thanks for clarifying. On the one hand, as is well known, Harvard’s undergrad student body does not mirror the country’s income/wealth distribution but is skewed toward the upper end. On the other hand, if you’re a Harvard student whose family income is below $100K/year, you don’t pay any tuition, room or board, and if family income is below $200K you don’t pay tuition as of this academic year (but still have to pay something toward room and board presumably). According to Dr. Google (apologies for trying to be funny), Harvard says that 55 percent of students receive some financial aid, which means 45 percent pay full freight (I’m not positive whether those figures refer only to undergraduates but I think so).

Elite reproduction exists, but it’s easy to fall into the inference that simply having an undergrad degree from Harvard or one of its elite peers is a guarantee of entrance into the elite (however defined). The inference is false. Conversely, while it may well be somewhat more difficult, it is quite possible to enter the elite or “the establishment” (however precisely defined) without having gone to an elite university.

Elite reproduction (or production) in other words is a rather inefficient (for lack of a better word) process as it works in the U.S., or so I would suggest. It’s not like one takes X number of high school seniors, puts them though four years of Harvard, Yale, Princeton, Duke, Stanford, Amherst etc. and you get X number of “successful” members of the elite. Instead, the number entering “the elite” is X – Y, where Y is a non-trivial number. That’s because, among other things, (1) not everyone who attends an elite university or college aspires to join the elite (as that phrase might be usually understood), and (2) of those who do aspire to join the elite, not everyone manages to do so (the identity of their alma mater notwithstanding). Of course one can have a very fulfilled (or whatever word you prefer) life without joining the elite, but that fact is not relevant to the particular question at hand.

J-D 08.28.25 at 2:17 am

Purely because you’re suggesting that this wording doesn’t completely satisfy you, I suggest the alternative of writing that ‘elite reproduction is only partly systematised’. (If that’s not what you’re seeking, sorry.)

engels 08.28.25 at 10:43 am

It’s not like one takes X number of high school seniors, puts them though four years of Harvard, Yale, Princeton, Duke, Stanford, Amherst etc. and you get X number of “successful” members of the elite.

IKR? Seriously, you make an important point, which according to Peter Turchin explains much about our tempestuous times:

https://nationalpost.com/opinion/peter-turchin-how-elite-overproduction-and-lawyer-glut-could-ruin-the-u-s

engels 08.28.25 at 1:07 pm

Turchin’s column also relevant to the “overeducation” point.

LFC 08.28.25 at 1:48 pm

@J-D: Yes, I think your word is better.

@engels: Thanks for the link.

ETB 08.28.25 at 6:05 pm

I mean, I wouldn’t, but I don’t know it’s any less intelligent than “let’s blame da kidz for studying gender politics at Uni and eating too much sushi”.

(Personally, speaking as a prole, I don’t think “blame the working class for climate change because they drive cars” is much different to “blame the working class for capitalism because they buy things on amazon”. Yes, “no such thing as ethical consumption under capitalism” is a warning and not an excuse, but also people respond to their material conditions. I’m not sure how someone can be so confident that redistribution of wealth, absent societal change, will solve overconsumption rather than largely redistribute it – for myself, I’d have thought there’d be something to investing in infrastructure to create new systemic dynamics to rebalance how material needs are met, but then I’m not a class reductionist).

“Complex human societies need elites – rulers, administrators, thought leaders – to function well,” Turchin writes. “We don’t want to get rid of them; the trick is to constrain them to act for the benefit of all.”

Odd to see a Marxist argue in favour of intraclass trumping interclass conflict, and for constraining rather than eliminating the elite, but then I’m one of those old fashioned people who view the stranglehold of the top 1% on the political, economic, and media spheres as a slightly more pressing issue..

engels 08.29.25 at 8:01 am

one of those old fashioned people

Life’s too short to unpick all the views you’re misattributing to me, ETB, but fyi the concept of the 1% dates from Piketty and Occupy.

engels 08.29.25 at 8:46 am

“Stop having children until everyone can afford 4 years doing this:”

https://www.theguardian.com/fashion/2025/aug/28/how-the-campus-became-the-new-catwalk

ETB 08.29.25 at 3:22 pm

It seems unlikely that the degree to which you’ve been unfairly characterised is notably higher that the degree to which you unfairly characterise others, and perhaps someone inclined to self-reflection might wonder if there the is some lesson to draw from that…

“With 1% of our people owning nearly twice as much as all the other 99%, how is a country ever to have permanent progress unless there is a correction of this evil?” Poster advertising “The American Progress” newspaper (ca. 1935).

As a helpful tip: if you’re going to employ pedantry in order to try to score cheap points, you might want to ensure you’re actually correct first :-)

engels 08.29.25 at 7:47 pm

It seems unlikely that the degree to which you’ve been unfairly characterised is notably higher that the degree to which you unfairly characterise others, and perhaps someone inclined to self-reflection might wonder if there the is some lesson to draw from that…

Something about “two wrongs” springs to mind.

ETB 08.29.25 at 9:10 pm

But presumably not so much “do unto others”…?

(the juxtaposition of 79, 80, and 82 is just chef’s kiss – truly a delight, and in these troubled times I do appreciate the entertainment!)

engels 08.30.25 at 12:53 pm

ETB, you’re right: if I’m continually misrepresenting your views in the same way you are mine then you have every right to decline to engage with me on that basis and you can have my word I shall not hinder you in any way when you do so.

ETB 08.30.25 at 7:14 pm

I always appreciate a gracious response, and indeed there are many ways that someone might choose in response to believing their views are not being treated with an appropriate degree of nuance and deference (e.g. changing one’s approach, responding to others instead, explaining those views in more detail, etc.). I have my preferences, which may quite reasonably differ from someone else’s (no doubt personal circumstance and predilections play a role).

However, it does seem to me that if someone proposes declining to engage should one feel misrepresented, then they already have in mind a method of which they may avail themselves…?

engels 08.31.25 at 2:16 pm

Indeed.

Tm 09.01.25 at 9:31 am

engels 69: “the richest 4% set to emit 13 times more carbon from their domestic travel than the poorest 14% by 2035”

Entirely plausible. Those poorest 14%, and probably more than that, are the ones who don’t own cars. The bulk of emissions are still caused by those in the middle, who own cars and fly. Is pointing that out somehow impolite? Then I apologize.

The article states: “A fairer approach, proposed by the IPPR, would focus on reducing excess private car travel and flights for those with the means to change their behaviours fastest, while increasing transport options for the least mobile.

It would not only promote a faster uptake of zero emission vehicles and sustainable aviation fuels, but also encourage less car use among all groups, increased use of public transport and active travel, such as cycling, and a significant reduction in flights for the highest emitting groups.” All of this would be great and all of it will be fiercely resisted not just by the richest but by the middle income people as well.

I don’t disagre that it would be good – good policy as well as good politics – to go after the richest highest consuming economic strata. But the majority is still likely to oppose any measures that make flying and driving more expensive. What do you suggest that would really cut down the emissions of the rich and that would be politically popular?

engels 09.01.25 at 11:44 pm

What do you suggest that would really cut down the emissions of the rich and that would be politically popular?

French word beginning with “g”…

engels 09.02.25 at 1:28 am

What do you suggest that would really cut down the emissions of the rich and that would be politically popular?

Talk about a softball question ;)

John Q 09.02.25 at 3:32 am

I’m calling a halt to this one. I’ll close comments when I get a moment, and delete any posted after this.

Comments on this entry are closed.