You searched for:

G.A. Cohen

(Originally drafted for a conference at Frankfurt in 2018 to mark the 40th anniversary of Karl Marx’s Theory of History: A Defence. I’ve done a bit of editing of my conference script and added a few footnotes etc, but it isn’t necessarily produced to the scholarly standards one might require of a journal article.)

In Karl Marx’s Theory of History, G.A. Cohen attributed many of the ills of capitalism to the market mechanism. Later in his career he came to see the market as practically ineliminable. Insofar as he was right about the market in his earlier work, it may turn out that the alternatives to capitalism he championed at the end of his life will also generate the pathology he deplored: the systematic bias in favour of output over leisure and free time. The following explores some of these tensions.

Introduction

In the second half of his career, G.A. Cohen concentrated his discussion of capitalism on its wrongs and injustices. According to his diagnosis, the primary injustice in capitalism arose from the combination of private property and self-ownership, which enables capitalists – who own the means of production – to contract with workers – who own only themselves and their labour power, on terms massively to the capitalists’ advantage. The workers, who produce nearly all of the commodities that possess value in a capitalist society, see the things that they have produced appropriated and turned against them as tools of exploitation and domination by the capitalists. But the wrongness and injustice of capitalism, the theft of what rightfully belongs to workers, is only one part of what is to be deplored about capitalism. In chapter 11 of Karl Marx’s Theory of History, a chapter where he went beyond the expository and reconstructive work he undertook earlier in the book, Cohen articulated a different critique, this time focused not on injustice but on the ills to which capitalism gives rise. In that chapter he attacks capitalism for stunting human potential through a bias towards the maximization of output, a bias which condemns human beings to lives dominated by drudgery and toil. Relatedly, he attacks capitalism both for stimulating demand for consumption that adds little of real value to people’s lives and because for damaging of the natural environment through pollution. In developing this critique, Cohen also notes that the bias towards output he identifies is celebrated by Max Weber as exemplifying rationality itself, a celebration which Cohen thought ideological and mistaken.1

Though both the wrongness and the badness of capitalism arise from the conjunction of private property and the market, it seems natural to emphasize the role of private property more in the production of injustice and to stress market relations more in the genesis of its badness. It is the fact of what the capitalists own that gives them decisive leverage over workers in the labour market, making exploitation within the workplace consequently possible; it is the market that compels everyone, capitalists and workers both on pain of extinction, to act in ways that end up being so destructive for human and planetary well-being.

Just when you think “he can’t possibly be saying that, there’s an obvious objection” – he anticipates, and replies … great stuff. From some time in the late 1980s.

The stupidest decision I made as an undergraduate was not to go to Jerry Cohen’s lectures on Marxism. The London colleges, despite being almost completely separate, pooled resources to give Philosophy lecture courses for 2nd and 3rd years. The lectures were held in tiny lecture rooms at Birkbeck – I seem to remember usually being there on Tuesday and Thursday mornings. The relevant term, Jerry’s lectures were on the same morning as the philosophy of language and philosophy of mind courses; I knew that I only had the concentration for 2, and, despite being, I presumed, some sort of Marxist (unaffiliated), I had no interest in political philosophy (not least because I believed some quite unsubtle version of Marx’s theory of history). (I’ll also admit that I responded somewhat to peer-pressure; my mate Adrian was not going to the Marxism lectures, and it was fun to have coffee with him instead). Like, as I later found out, Jerry, I had not come to study philosophy in order to learn about political ideas – I’d been politically active since I was 15 and had been exposed to all the political ideas that implied while I was in secondary school (taught History by a member of the CPB (M-L); indirectly recruited to the peace movement by a former CPGBer; worked with someone in the NCP, various SWPers; engaged in conspiratorial faction fights within the peace movement against various Trotskyists including CB’s flatmate of that time… you get the idea). I went to university to study something that I knew I couldn’t learn any other way – analytical philosophy. So it was easy to pass up Jerry’s lectures, even though everyone said they were brilliant, and even though I was interested in Marxism.

Later Jerry influenced me enormously. I bought Karl Marx’s Theory of History A Defence

as a celebration of getting my degree and read it first on a trip after graduating; I studied it about half-way through graduate school (along with these papers by Levine and Wright, and Levine and Sober), and more than anything else was responsible for my shift away from philosophy of language to political philosophy; because, like most readers of KMTH, I became convinced that the version of Marx’s theory of history that had seemed to me to make political philosophy irrelevant was false. I then read what is still my favourite Jerry paper, “The Structure of Proletarian Unfreedom”, and subsequently saw him lecture at UCLA; from then on I guess I read nearly everything he published, as soon as I could get my hands on it.

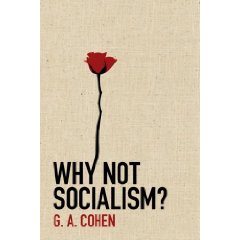

So now, what I presume is his final book, Why Not Socialism? (UK

) (I hope there’ll be other publications – presumably someone, probably one of our readers, is taking responsibility for seeing some of the work that Jerry left unpublished into print) is in my hands. Princeton have deliberately created it to be like On Bullshit

– very short, beautifully made, small enough to fit in a smallish pocket. People have been calling it the “camping trip” book; he uses the conceit of a camping trip to demonstrate that organizing social life around the two principles that, for him, define socialism – a very stringent version of equality of opportunity, and a very demanding principle of community – is very appealing to most people in some circumstances. He goes on to demonstrate that the appeal of these principles is not superficial, or restricted to unusual circumstances such as a camping trip, but are appealing at a society-wide level too:

Disclaimer: oddly, given my interests, I’ve never read much G.A. Cohen before picking up Rescuing Justice and Equality for this little event. (I understand his friends call him ‘Gerry’, but I won’t presume, on such slight acquaintance.) This matters only because my reading of the book is still preliminary and a bit scattershot. I’m not sure I get it. Also, I typed this post out like a maniac, just for the exercise of it. Also, I’m writing this post without access to my Rawls books, which I forgot to bring home, so I can’t quote. Well, I’m sorry about that. So stuff I say that is just plain wrong should be corrected in comments, without anger if you please. And we’ll just do our best, shall we? Also, I’m about to go on vacation for a few days, but I promised to participate. Also, I’m about to embark on an internet-free weekend getaway. Hence will not be very helpful in comments myself. Best I can do.) [click to continue…]

Speaking of G.A. Cohen, “Philosophy Bites” has a brief interview (less than 11 minutes) with him that serves as a nice introduction to his thought.

There are two upcoming events in memory of G.A. (Jerry) Cohen, who died last year. The Philosophy Department at University College London, where Jerry taught from 1964 to the mid-1980s, is holding a reception at 5pm on Thursday 17 June at 19 Gordon Square (“details”:http://www.ucl.ac.uk/philosophy/ ) and two days later, on Saturday 19th June, there will be a memorial service at at All Souls College Oxford, where Jerry spent the remainder of his career ( 2.15pm in the Codrington Library). Myles Burnyeat, John Roemer, T. M. Scanlon, and Philippe Van Parijs will be

speaking at the All Souls memorial.

I got a call this morning to tell me that Jerry (G.A.) Cohen has died suddenly and unexpectedly of a massive stroke. I want to write an appreciation of him as a friend, mentor and philosopher in due course, but I’m too numb to do it at the moment. I know that his other friends, colleagues and fellow students of his feel the same acute sense of loss.

Those who enjoyed our reading group on Rescuing Justice and Equality can now listen to the Center for the Study of Social Justice conference honouring G.A. Cohen on your ipods, courtesy of Oxford University podcasts (scroll about half way down the page to the Department of Politics and International Relations — if someone can find a handier way to link to them, please tell me). Speakers include John Roemer, Seana Shiffrin, Michael Otsuka, Cecile Fabre, Paula Casal, David Miller, David Estlund and Andrew Williams. The audio quality is a bit rough in places, but mostly good, and always good enough. (You can also get there on iTunes, but I can’t figure out how to link to that. In the iTunes store just search for CSSJ. As a bonus, if you search for Hartry Field, you get to his 2008 John Locke Lectures). As a bonus, you can hear Roemer explain why he came to believe that all philosophers are idiots.

First of all, sorry that this has taken so long. What follows are some reflections on ch. 4 of G.A. Cohen’s _Rescuing Justice and Equality_. I _think_ I’ve got the basic argument right, but I’d welcome corrections and clarifications.

The key shock of this chapter is Cohen’s rejection of the difference principle itself as a basic principle of justice. In the earlier chapters, Cohen focused on the fact that the inequalities supposedly justified by the difference principle might often be the result of more talented people holding out for higher pay, despite the fact that they could perfectly well supply their labour for less. To act thus, is, according to Cohen inconsistent in people who affirm a commitment to the difference principle (as _ex hypothesesi_ all citizens of the well-ordered society do). Contra Rawls and most Rawlsians then, Cohen there argued that the difference principle ought to mandate a more equal society than is commonly supposed, because most applications of the standard incentives argument ought to fail. It isn’t that we must pay the talented more because otherwise they won’t be able to supply the labour that benefits the least advantaged; it is that they choose not to supply it unless they are bribed. But a person sincerely committed to maximizing the expectations of the least advantaged wouldn’t need to be bribed.

Chapter 2 of G.A. Cohen’s new _Rescuing Justice and Equality_ addresses an argument in favour of the difference principle put by Brian Barry (as a reconstruction of Rawls) in his _Theories of Justice_. The argument has two stages: in the first, an equal distribution is established as the only _prima facie_ just distribution; in the second, a move away from equality is licensed, so long as it is a move to a Pareto superior distribution. Barry’s argument for the first stage is essentially that there is no cause of an unequal distribution that would justify its inequality: so there is, at a fundamental (i.e. pre-institutional) level, no argument based on desert or entitlement that would provide a justifying explanation of an unequal distribution. Such inequalities, are therefore, so this argument claims, _morally arbitrary_. The argument for the second stage is consequentialist: it would be irrational to insist on an equal distribution if it were possible to move from it to a distribution where some people were better off and none were worse off. (Insisting on equality in these circumstances looks like a levelling-down.)

From the point of view of Cohen’s engagement with Rawls, it is hard (for me) to see that this chapter adds much to the previous one. Cohen invites us to imagine an initially equal distribution D1 and a Pareto superior distribution D2. It looks as if we should prefer D2 to D1, because some people do better and no-one does worse. But, he says, let’s imagine another equal distribution, D3 which is Pareto superior to D1. Why couldn’t we move from D1 to D3 (rather than D2)? He canvasses various explanations, but the central point, as before is that the naturally-talented are only willing to put the additional (worst-off improving) effort in under conditions of inequality (D2) rather than under the equal net reward available under D3. There isn’t, therefore, an objective barrier to the feasibility of equality at the D3 level, just a justice-denying choice on the part of the already talented.

The real interest of the chapter lies, I think, elsewhere and is hinted at by Cohen in his reference to Nozick at p.90 fn. 11. It is the assumption, which Barry clearly shares, that the removal of the morally arbitrary causes of the holdings that people have ought to privilege equality as the just initial distribution. Why isn’t equality just as morally arbitrary as an initial starting-point as inequality? This, of course, is the point pressed by my late colleague Susan Hurley in her _Justice, Luck and Knowledge_ (esp. ch. 6). The right response to that worry is to provide a positive argument for equality as a morally privileged starting-point rather than relying on it being some default position after the removal of morally unequalizing arbitrary factors.

[Remember the rules: no commenting unless you’ve read the book.]

As promised, this is the first in a series of weekly postings on G.A. Cohen’s new _Rescuing Justice and Equality_. I say “new”, but much of the book isn’t all that new at all and consists of the republication of older material with which the political philosophy community is already familiar. I should also mention that there’s a conference on the book in Oxford on Friday and Saturday, which I’ll be attending, so my contribution in future weeks will, no doubt, be enriched by that. But for now it has not been.

A month ago I proposed an online reading group for G.A. Cohen’s _Rescuing Justice and Equality_. (“US Amazon”:http://www.amazon.com/exec/obidos/ASIN/0674030761/junius-20 , “UK Amazon”:http://www.amazon.co.uk/exec/obidos/ASIN/0674030761/junius-21 ) It is time to get started. I’ll kick-off a week from today with a post covering the introduction and chapter 1, “Rescuing Equality from ….The Incentives Argument”. We’ll then cover a chapter a week (plus the general appendix) with, I hope, other people sometimes taking the lead. Remember the rules: a condition of commenting is that you’ve actually read the text under discussion (violators will be deleted).

I’ve suggested to some of the other CTers that we should have an online reading group on G.A. Cohen’s _Rescuing Justice and Equality_ (“Amazon”:http://www.amazon.com/exec/obidos/ASIN/0674030761/junius-20 , “Amazon.uk”:http://www.amazon.co.uk/exec/obidos/ASIN/0674030761/junius-21). They can’t do it until January, so this is a heads-up. When we get started we’ll cover a chapter a week, with maybe different people taking the lead (Harry, Ingrid, Jon? …) and then comments will be open. But a condition of commenting is that you’ve actually read the text under discussion (violators will be deleted). So if you want to take part you need to get the book, and you need to get reading and thinking.

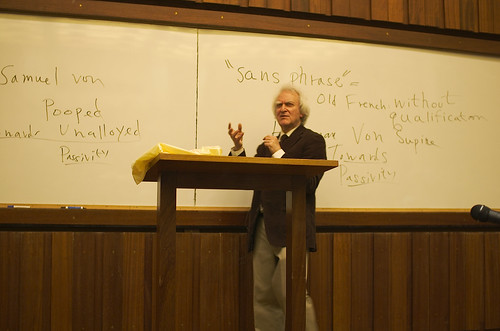

Many of his friends. colleagues and former students were present at a wonderful performance from Jerry Cohen (G.A. Cohen) yesterday. Jerry is retiring as Chichele Professor and gave his valedictory lecture. Here Jerry recreates Isaiah Berlin explaining the influence of the altogether neglected Samuel von Pooped on the totally forgotten Herman von Supine.

Thank you to Ingrid for introducing me, and to all current members of the Crooked Timber for welcoming me on board. I am a long term fan of the Crooked Timber (since my days as a graduate student, in fact!) and therefore really excited to be joining the team.

I would like to kick off by elaborating on some thoughts that I have only briefly mentioned in a recent piece. The basic idea, in a nutshell, is the following: could it be that we sometimes have reason to be more radical under non-ideal circumstances than under ideal ones?

The reason why this might seem initially puzzling – it definitely is to me – lies in the fact that, by definition, non-ideal theory falls short of ideal theory in important ways. Sure, the suggestion is often made that our obligations of justice under non-ideal circumstances might become more demanding – simply because we might be required to compensate for the non-compliance of other duty bearers (although some people want to resist that thought ). This, however, is a point about the demandingness of our duties, not about how radically our aims should diverge from the status quo. When it comes to what we should be aiming at, rather than how much effort we should put into it, non-ideal theory is usually depicted at giving us targets that are closer to home. We should be more modest, we should not demand too much. We cannot have a truly egalitarian society, but we can maybe try and aim for a more humane one than the one we currently have. We cannot have gender equality, but we can maybe narrow the gap. We cannot put an end to capitalism, but maybe we can tame it just a little bit. The most obvious way in which this approach plays out is in the chase of the political centre by the mainstream left, which has been making social-democratic agendas ever more lukewarm over the last three decades.

However, the relationship between ideal and non-ideal theory does not always have to work that way. [click to continue…]