by John Q on August 1, 2020

Ever since I wrote Work for All with Australian MP John Langmore back in 1994, I’ve been pushing the idea that a path to full employment requires an expansion of publicly provided services. For about the same length of time, Bill Mitchell (also an Australian economostO has been putting forward similar (but not identical) proposals. At some point in this process, Bill became one of the advocates of what’s called Modern Monetary Theory, which makes the point that taxes don’t (directly) “fund” public expenditure. Rather, they ensure that the total demand for goods and services (for consumption and investment) don’t exceed the productive capacity of the economy, thereby generating inflation.

This reframing raises the question: does a Job Guarantee require higher taxation? The answer, using MMT reasoning, is “Almost certainly, yes”.

[click to continue…]

by Henry Farrell on July 20, 2020

This Paul Krugman column helped crystallize the weirdness of the ongoing economists versus epidemiologists spat, perhaps more accurately described as the ‘some economists, especially those with libertarian politics, versus epidemiologists spat.’ Different theories, in turn below the fold.

[click to continue…]

by John Q on June 1, 2020

I’ve been working for some time on a review of the first full-length text based on Modern Monetary Policy, Macroeconomics by William Mitchell, Randall Wray and Martin Watts. A near-final draft is over the fold

[click to continue…]

by Henry Farrell on May 12, 2020

An addendum to my earlier post, to explain more directly why I am skeptical of the argument that public choice is a useful lens to understand the politics of the public during coronavirus. Shorter version: if the “public” is indeed some kind of equilibrium, then the underlying game is unlikely to be the kind of game that public choice scholars like to model. [click to continue…]

by Henry Farrell on May 5, 2020

Tyler Cowen quotes approvingly from a Robin Hanson post (the URL suggests that the original title of Tyler’s post was “On Reopening, Robin Hanson is Exactly Correct).

While the public tends to defer to elites and experts, and even now still defers a lot, this deference is gradually weakening. We are starting to open, and will continue to open, as long as opening is the main well-supported alternative to the closed status quo, which we can all see isn’t working as fast as expected, and plausibly not fast enough to be a net gain. Hearing elites debate a dozen other alternatives, each supported by different theories and groups, will not be enough to resist that pressure to open.

Winning at politics requires more than just prestige, good ideas, and passion. It also requires compromise, to produce sufficient unity. At this game, elites are now failing, while the public is not.

… More broadly, this is an example of why we need public choice/political economy in our models of this situation. It is all about the plan you can pull off in the real world of politics, not the best plan you can design. A lot of what I am seeing is a model of “all those bad Fox News viewers out there,” and I do agree those viewers tend to have incorrect views on the biomedical side.

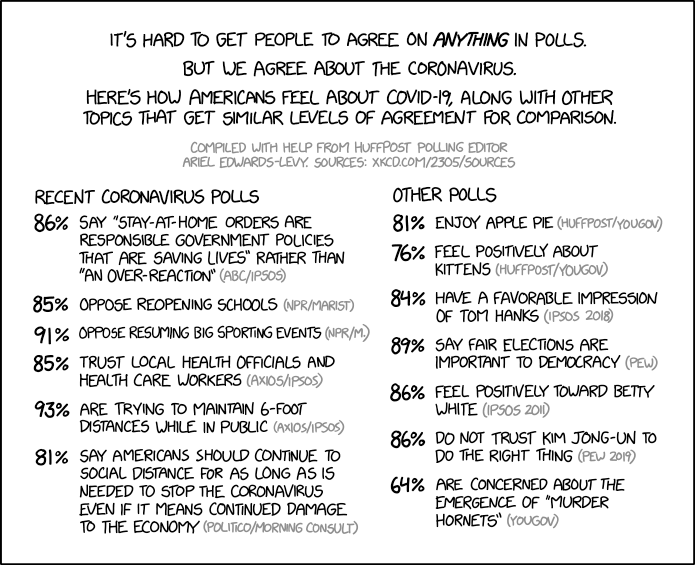

This all begs an obvious question: who exactly is the “public” that they are talking about? [click to continue…]

by John Q on March 20, 2020

Last year I published a book chapter arguing that the first step way to get to a Universal Basic Income in Australia was to expand the existing benefit system, increasing payments and removing conditionality (relevant extract over the fold).

This is often called a Guaranteed Minimum Income (GMI). I counterposed the GMI approach to the alternative of making a small payment to everyone in the community, and then trying to increase it over time. I suggested three initial steps

Assuming a ‘basic first’ approach is preferred, how might it be implemented? Three initial measures might be considered:

(i) increase unemployment benefits, at least to the poverty line;

(ii) replace the job search test for unemployment benefits with a ‘participation’ test;

(iii) fully integrate the tax and welfare systems

We are already on the way to taking these steps. Having floated the idea of a separate benefit for people who lose their jobs due to the virus crisis, the Australian government has quickly abandoned it in favour of an increase in existing benefits. This is supposed to be temporary, and, in theory, at least, there has been no change in compliance efforts like work testing. But ‘temporary’ will turn out to be a long time, and compliance efforts are going to be impossible until things return to normal.

[click to continue…]

by Chris Bertram on February 20, 2020

I have a [new piece up at the LRB blog on the UK’s post-Brexit immigration plans](https://www.lrb.co.uk/blog/2020/february/who-will-pick-the-turnips). I argue that at the core of the plans is an intention to treat EU migrants and others as a vulnerable and exploitable workforce and that the logic of denying a long-term working visa route to the low paid leads to three possibilities: either the businesses that rely upon them will go bust, technology will substitute for labour, or the UK will have to start denying education to young Britons so that they become willing to be the underpaid workforce that picks turnips and cleans the elderly in social care.

by John Q on October 27, 2019

… what replaces it will be even worse. That’s the (slightly premature) headline for my recent article in The Conversation.

The headline will become operative in December, if as expected, the Trump Administration maintains its refusal to nominate new judges to the WTO appellate panel. That will render the WTO unable to take on new cases, and bring about an effective return to the General Agreement on Trade and Tariffs (GATT) which preceded the WTO.

An interesting sidelight is that Brexit No-Dealers have been keen on the merits of trading “on WTO terms”, but those terms will probably be unenforceable by the time No Deal happens (if it does).

by John Q on September 24, 2019

Looking for a different story in the business pages of The Guardian, I happened across a headline stating The men who plundered Europe’: bankers on trial for defrauding €447m. That attracted my attention, but the standfirst, in smaller print, was even more startling

Martin Shields and Nick Diable are accused of tax fraud in ‘cum-ex’ scandal worth €60bn that exposes City’s pursuit of profit

I think of myself as someone who pays attention to the news, but I had missed this entirely. Google reveals essentially no coverage in the main English language media. There’s a short but helpful Wikipedia article and that’s about it. The scandal has been described as the ‘crime of the century’, but it’s just one of many multi-billion dollar/euro heists, with the GFC towering above them all.

It remains to be seen how the trial will turn out, but it’s already clear that, as usual, the banks have got away with it. The bank most closely involved in the scam, HypoVereinsBank in German has set aside €200 million euros to cover its potential liability. That’s less than 1 per cent of the tax avoided or evaded (the lawyers will be fighting out which, for some time, but the effect on ordinary citizens is the same).

The crucial point here isn’t the failure of the law to punish wrongdoing.

What matters is that crooked deals of this scale suffice for a complete explanation of the growth of the global financial sector since the 1970s. The point of the financial sector is not to allocate capital more efficiently, but to undermine the regulatory and tax systems that are supposed to make the economy work properly. Unsurprisingly the huge financial boom has been accompanied by miserable productivity growth, repeated business collapses and massive growth in inequality.

The only way to fix the problem is to shrink the financial sector to a tiny fraction of its current size, and tightly regulate what remains. The rational route to achieve this would start with the kinds of reforms being proposed by Elizabeth Warren. But we may be stuck with a messier path, in which courts tire of giving slaps on the wrist to recidivist banks and start shutting them down.

[click to continue…]

by Ingrid Robeyns on September 21, 2019

I have no idea how he found it, but George Monbiot read an (open access) academic article that I wrote, with the title “What, if Anything, is Wrong with Extreme Wealth?‘ In this paper I outline some arguments for the view that there should be an upper limit to how much income and wealth a person can hold, which I called (economic) limitarianism. Monbiot endorses limitarianism, saying that it is inevitable if we want to safeguard life on Earth.

As Monbiot’s piece rightly points out, there are many reasons to believe that there should be a cap on how much money we can have. Having too much money is statistically highly likely to lead to taking much more than one’s fair share from the atmosphere’s greenhouse gasses absorbing capacity and other ecological commons; it is a threat to genuine democracy; it is harmful to the psychological wellbeing of the children of the rich, and to the capacity of the rich to act autonomously when it concerns moral questions (which includes the reduced capacity for empathy of the rich); and, as I’ve argued in a short Dutch book on the topic that I published earlier this year, extreme wealth is hardly ever (if ever at all) deserved. And if those reasons weren’t enough, one can still add the line of Peter Singer and the effective altruists that excess money would have much greater moral and prudential value if it were spent on genuine needs, rather than on frivolous wants.

Monbiot wrote: “This call for a levelling down is perhaps the most blasphemous idea in contemporary discourse.”

[click to continue…]

by John Q on August 18, 2019

That’s the provisional title I used for my latest piece in Inside Story. Peter Browne, the editor, gave it the longer and clearer title “Want to reduce the power of the finance sector? Start by looking at climate change”.

The central idea is a comparison between the process of decarbonizing the world economy and that of definancialising it, by reducing the power and influence of the financial sector. Both seemed almomst impossible only a decade ago, but the first is now well under way.

There’s also an analogy between the favored economists’ approach in both cases: reliance on price based measures such as carbon taxes and Tobin taxes. Despite the theoretical appeal of such measures, it looks as if regulation will end up doing much of the heavy work.

by Chris Bertram on August 7, 2019

I’ve recently been in Germany which, to a greater extent than many other countries (such as my own), is a functioning and prosperous liberal democracy. It wasn’t always thus, as every participant in internet debate know very well. By the end of the Second World War, Germany had suffered the destruction of its cities and infrastructure, the loss of a large amount of its territory, and the death or maiming of a good part of its population and particularly of the young and active ones. Yet, though not without some external assistance, it was able to recover and outstrip its former adversaries within a very few decades.

Thinking about this made me reflect a little on whether people, in the sense of talented individuals, matter all that much. That they do is presupposed by the recruitment policies of firms and other institutions and by immigration policies that aim to recruit the “best and brightest”. Societies are lectured on how important it is not to miss out in the competition for “global talent”. Yet the experience of societies that have experienced great losses through war and other catastrophes suggests that provided the institutions and structures are right, when the “talented” are lost they will be quickly replaced by others who step into their shoes and do a much better job that might have previously been expected of those individuals.

I imagine some empirical and comparative work has been done by someone on all this, but it seems to me that getting the right people is much less important that having the institutions that will get the best out of whatever people happen to be around. I suppose a caveat is necessary: some jobs need people with particular training (doctoring or nursing, for example) and if we shoot all the doctors there won’t yet be people ready to take up the opportunities created by their vacancy. But given time, the talent of particular individuals may not be all that important to how well societies or companies do. Perhaps we don’t need to pay so much, then, to retain or attract the “talented”: there’s always someone else.

by John Q on June 29, 2019

I’ve been busy for the last week doing events for Economics in Two Lessons, so I didn’t have time to take part in the discussion arising from Harry’s post on alternatives to Sanders’ proposal to wipe out college debt.

In one way, that’s a pity because the key point of the book is the idea of opportunity cost – the true cost of anything, for us as individuals, and for society as a whole, is what you must give up to get it. More precisely, it’s the best alternative available to us.

Harry’s post was all about opportunity cost – what would be the best use of $1.6 trillion in public funds. However, the discussion was inevitably enmeshed in the complexities and inequities of US education, while comments making broader arguments about opportunity cost reasoning weren’t discussed in detail.

One of those broader arguments is the idea that, thanks to Modern Monetary Theory, there’s no need to worry about such questions. In the “chartalist” reasoning underlyng MMT, the fact that governments can issue their own sovereign currency means that there is no need to “finance” public spending by taxation; rather taxation is a tool used to manage aggregate demand so as to keep the economy fully employed but not at a point where excess demand creates inflation. That (essentially correct) position can easily slide into the (only subtly different, but radically mistaken) view that governments can spend money on anything they like with no need for any increases in taxes or cuts in other spending.

As I will argue over the fold, a correct version of MMT makes no such claim. Unfortunately, while avoiding the error themselves, a lot of MMT theorists have not shown much willingness to set their more naive followers straight.

[click to continue…]

by Chris Bertram on June 11, 2019

I’m nearly through reading Barbara Kingsolver’s *The Poisonwood Bible* at the moment, and very good it is too. For those who don’t know, the main part of Kingsolver’s novel is set in the Congo during the period comprising independence in 1960 and the murder of its first Prime Minister, Patrice Lumumba, on 17 January 1961 at the hands of Katangan “rebels” backed by Belgium and the US. And DR Congo (sometime Zaire) has been pretty continuously violent and unstable ever since. With its origins in King Leopold’s extractive private state (rubber), Congo has been coveted and plundered for the sake of its natural resources ever since. At the time of the Katanga crisis copper was the thing. But now what was previously a little-wanted by-product of copper extraction, cobalt, is in heavy demand because of its use in batteries.

My attention was caught yesterday by [a press release from the UK’s Natural History Museum](https://www.nhm.ac.uk/press-office/press-releases/leading-scientists-set-out-resource-challenge-of-meeting-net-zer.html), authored by a group of British geoscientists:

> The letter explains that to meet UK electric car targets for 2050 we would need to produce just under two times the current total annual world cobalt production, nearly the entire world production of neodymium, three quarters the world’s lithium production and at least half of the world’s copper production.

A friend alerted me to a piece by Asad Rehman of War on Want, provocatively entitled [*The ‘green new deal’ supported by Ocasio-Cortez and Corbyn is just a new form of colonialism*](https://www.independent.co.uk/voices/green-new-deal-alexandria-ocasio-cortez-corbyn-colonialism-climate-change-a8899876.html) which makes the point:

> The demand for renewable energy and storage technologies will far exceed the reserves for cobalt, lithium and nickel. In the case of cobalt, of which 58 per cent is currently mined in the DR of Congo, it has helped fuel a conflict that has blighted the lives of millions, led to the contamination of air, water and soil, and left the mining area as one of the top 10 most polluted places in the world.

People who are optimistic about the possibilities of decarbonizing without major disruption to Western ways of life and standards of living are often enthusiastic about new technologies, battery developments etc. I’ll include CT’s John Quiggin in that (see John’s piece from CT [Can we get to 350ppm? Yes we can from 2017](https://crookedtimber.org/2017/07/22/42710/)). John tells me he’s sceptical about claims that we are about to run out of some scare resource. Maybe he’s right about that and more exploration will reveal big reserves of copper and cobalt in other places. But even if he is, we still have to get that stuff out of the ground, and that’s predictably bad for local environments and their people, and in the short to medium term it may yet be further bad news for the people of DR Congo who have already endured seventy plus plus years as a “free” country (and 135 years since Leopold set up in business) in conditions of violence and exploitation, whilst already wealthy northerners get all the benefits.

by John Q on June 9, 2019

The term “globalization” came into widespread use in the 1990s, about the same time as Fukuyama’s End of History. As that timing suggests, globalization was presented as an unstoppable force, which would break down borders of all kinds allowing goods, ideas, people and especially capital to move freely around the world. The main focus was on financial markets, and the assumption was that only market liberal institutions would survive.

The first explicit reaction against globalization to gain popular attention in the developed world[1] was the Battle of Seattle in 1999, but the process, and the neoliberal ideology on which it rested, didn’t face any serious challenge until the Global Financial Crisis of 2008. The Crisis destroyed Neoliberalism as a political project with positive appeal, but its institutions have remained in place through inertia.

Now, however, globalization is finally facing serious threats, most immediately from the nationalist[2] right, seeking to restrict movement of people and goods across national borders. There hasn’t yet been any serious challenge to financial globalization, but faith in the wisdom and beneficence of financial markets has disappeared.

An obvious question here is: can globalization be reversed? My short answer is: within current political limits globalization can be reversed least partially in the case of trade, but can only be slowed in the case of movements of people. I’m still thinking about financial flows.

[click to continue…]