(Author’s Note: this following was published in the “Tales Out of School” column of the Winter 2015 edition of Andover Magazine. I thought the Crooked Timber community might find it of interest, as well.)

We weren’t walking like animals with horns.

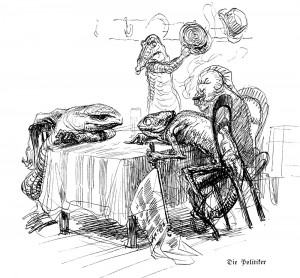

“Rappelez-vous, vous êtes des rhinocéros!” exhorted Mr. Sturges, swinging his own head ponderously back and forth in the approximation of a rhino’s. And so we moved, on all fours in a chilly classroom in Sam Phil, trying for all the world to embody the humans in Ionesco’s play who find themselves transformed into prehistoric animals.  Back in our seats, having resumed our student forms, we had a new appreciation for Rhinocéros, a play about conformity and existentialism in the context of the absurd.

Hale Sturges didn’t just teach French literature; he lived it. He sat on his desk; he paced around the room; he jumped up and down, his corduroy blazer flapping. He believed that the oral tradition was essential to understand literature, so we took turns reading Camus’ The Stranger aloud to better appreciate the alienation of the protagonist, Meursault.

A class was not a monolith to Mr. Sturges. Rather, students were individuals whom he evaluated, coached, and supported in their pursuit of mastering French language and culture. On one occasion, we were tasked with independent research and an oral presentation on one aspect of the art history of France. Decades before PowerPoint, daunted by the prospect of an audiovisual presentation, I managed a few clumsy slides on the Impressionists.

After class, Mr. Sturges gestured for me to stay behind. He told me gently that my presentation had been mediocre. He went on to say that he was taking the time to speak with me about it because he knew that I was capable of much more. I squirmed and fought back tears of embarrassment during his critique; I knew he was right.

French has enhanced my life in ways I barely imagined in high school. I’ve studied and worked in France, Morocco, Benin and Mali, the language opening doors that would be otherwise impenetrable to an American. I’ve always been grateful to Mr. Sturges for giving me the confidence and the desire to immerse myself in France’s language, literature and culture.

When I read the call for submissions to Tales Out of School asking for reflections on especially innovative teachers, I thought immediately of Mr. Sturges. I was stunned and saddened to learn that he had passed away just a few weeks earlier.

But his legacy endures. Next year, my own children will have the opportunity to experience French language and culture firsthand when we live in Paris while I spend a month as a visiting scholar at Sciences Po.

Thanks to Mr. Sturges, I can’t wait to play rhinoceros with them.