by Kevin Munger on October 17, 2023

Accelerating change has become both addictive and intolerable. At this point, the balance among stability, change, and tradition has been upset; society has lost both its roots in shared memories and its bearings for innovation…An unlimited rate of change makes lawful community meaningless.

Ivan Illich, Tools for Conviviality

The ideology of Silicon Valley is clear: move fast and break things, scale at all costs, pump and dump. The lingering earth-flavored utopianism of the California Ideology softened the edge, and American two-party politics ensured at least a facade of responsibility, but both have largely fallen away over the past year.

[click to continue…]

by Chris Bertram on October 15, 2023

by Chris Armstrong on October 12, 2023

I was meant to write a post this week, but then Hamas’s horrific assault on Israel happened, and now the civilian inhabitants of Gaza are once again living in fear (some of them have put themselves in the firing line; many have not). Since I have Arab friends and family, and have fond memories of Gaza, it all feels horribly close to home, and yet also impossibly distant. But of course, it has never been easy to know what to say about Gaza.

In the meantime, for a good example of what *not* to say about Gaza, you could try

this piece. (In a nutshell, Yuval Noah Harari’s solution seems to be that Israel hands the problem over to a coalition of the willing who will administer Gaza colonial-style. I can envisage a few problems).

by John Q on October 8, 2023

by Chris Bertram on October 8, 2023

by John Q on October 3, 2023

It’s a movie we’ve seen over and over again in US politics. Centrists engage in respectful discussion with a thoughtful conservative[1], only to discover they are actually talking to a dishonest troll. Yet, just like Charlie Brown lining up to kick Lucy’s football, they keep coming back for another try.

Examples include Paul “policy wonk” Ryan, JD “voice of the heartland” Vance, and most recently Richard Hanania, for whom I can’t come up with a suitable nickname. Hanania’s public writing has always skirted the edge of outright racism, so it was no surprise when it turned that he had published far worse stuff under a pseudonym. That was enough to lead Bari Weiss to cancel him, but the majority reaction among his interlocutors was to accept a redemption narrative.

Hanania rewarded his backers with a tweet so breathtakingly dumb it’s still hard to believe. Challenged on his opposition to aiding Ukraine, he asserted that the US was spending 40 per cent of GDP on such aid, and laid out some of the alternative ways the money could be spend (years of funding for social security, for example).

This claim was so absurd that lots of people looked for an 11-dimensional chess explanation. Sadly, the prosaic explanation appears to be that US aid is equal to about 40 per cent of Ukraine’s GPD. Hanania must have read this number and misinterpreted it. That could only be done by someone utterly clueless about economics and public policy, but Hanania hasn’t needed a clue to become a big fish in the small pool of rightwing intellectuals.

Why do centrists keep falling for this? The answer, to paraphrase Voltaire is that, since no-one like the imagined intelligent, honest conservative exists, they have to be invented. In reality, intelligent honest conservatives, are either ex-Republicans (for example, David French and the Bulwark group) or open enemies of democracy (Adrian Vermeule).

But once they recognise that there is no serious thought to their political right, centrists would have to recognise that they themselves are the conservatives. That would entail an intellectual obligation to engage with the left, which is the last thing they want.

[click to continue…]

by Harry on October 2, 2023

If you haven’t yet listened to Emily Hanford’s Sold a Story, you probably should, now. It’s brilliant, if profoundly depressing. Very brief synopsis: the methods routinely used to teach children to read in the US don’t work well for large numbers of children, and the science of reading has been clear about this for decades. Three academics in particular — Lucy Calkins of Teachers College, and Irene Fountas and Gay Su Pinnell of the Ohio State University — are responsible for promoting these bad practices (which are pervasive), and persisted in doing so long after the research was clear, and have gotten very rich (by the standards of academics) from the curriculum sales/speaking circuit.[1] Hanford’s documentary has single-handedly changed the environment, and in the past couple of years State departments of education and even school districts throughout the country have been scrabbling to reform, often under the eye of state legislators who have been alerted to the situation by the amount of chatter that Sold a Story has generated.

Go and listen to it.

Although a great admirer of Hanford’s work, which I have known and followed for many years, it took me a while to listen to Sold a Story. By the time I did I was familiar with the basic narrative which, I think, freed my mind to wonder about something that Hanford doesn’t discuss. The role of academic bystanders. People like me.

[click to continue…]

by Chris Bertram on October 1, 2023

by Eric Schliesser on September 29, 2023

A few weeks ago, Cyril Hédoin responded insightfully and constructively (here) to an essay I recently published @Liberal Currents. Subsequently, he did a follow up piece in which he assimilated my stance on what I call the ‘platonic skepticism’ (more on that below) of liberalism into a larger framework about different kinds of skepticism exhibited by liberals.

In the piece that triggered Hédoin’s response, I argued that so-called public reason liberalism (made influential by Rawls) and French Laïcité, or radical secularism, share three features: (i) they transcend the right/left opposition, (ii) they demand considerable public censorship, and (iii) they are both grounded in a Platonic skepticism about the ability of truth to dominate mere opinion in a democratic context.* My own alternative (liberal) position, accepts a version of (iii), but rejects (i-ii) as inimical to healthy liberal political life. So far so good.

[click to continue…]

by Kevin Munger on September 26, 2023

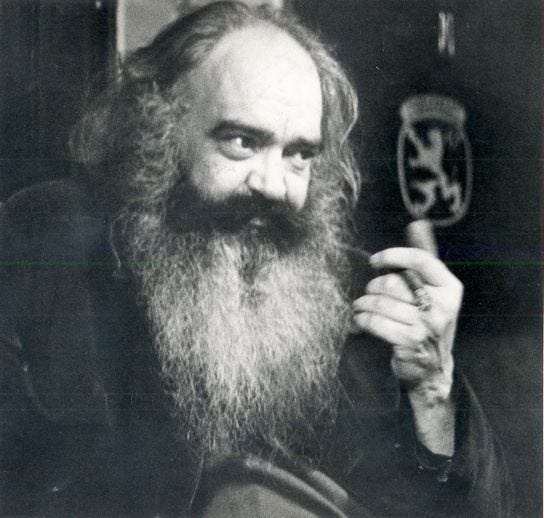

During the pandemic, I was seduced by a charming British management consultant. A debonair James Bond-type who went from driving a Rolls Royce around his countryside estate to orchestrating the Chilean economic experiment under Allende to teaching Brian Eno about the principles of complex systems in a stone cottage in Wales. Stafford Beer lived a remarkable life,

What the abandonment of the pinnacle of capitalist achievement for the most realistic effort to build cybernetic socialism does to a mfer.

[click to continue…]

by Chris Bertram on September 24, 2023

by John Q on September 22, 2023

It’s time for me to have my final say on a dispute with Matt Yglesias that has been going at a fairly slow pace.

A couple of weeks ago, Matt put up a post (really a Substack newsletter, but I still think in blog terms), headlined Polarization is a choice with the subtitle, “Political elites justify polarizing decisions with self-fulfilling prophesies”

I responded with a snarky but (I thought) self-explanatory note, saying “Peak both sidesism here. Republicans want to overthrow US democracy, while Democrats stubbornly insist on keeping it. Surely there is some middle ground to be found here ”

A few days ago, Matt came back to ask “I’m curious what actual things the article says you believe are wrong. You clearly didn’t like it since you choose to mischaracterize it in a mean-spirited way, but I’m not sure what you didn’t like about it.”

So, here’s my response.

[click to continue…]

by John Q on September 19, 2023

That was my suggested headline for my latest opinion piece, which ran in Australian online magazine Crikey under the sub-editors (blander IMO) choice of “We don’t need a nuclear renaissance. We need a solid plan on renewables”

The idea of the piece was to respond to Exhibit A in the case for nuclear power, the successful French construction program of the 1970s and 1980s, under the Messmer Plan. I’ve previously written about the way this program depended on the power of the French state at the time, which can’t easily be replicated today. A little while ago, I was suddenly struck by the thought that the Messmer Plan would have been much more effective if it were applied to solar and wind energy rather than nuclear. It’s over the fold (I’ve removed the lead, linking to current Australian politics)

[click to continue…]

by Chris Bertram on September 18, 2023

Sorry, when you are semi-retired and in France anyway, easy to forget days of the week. Here’s an iPhone photo, from when I happened to be out and about in Pézenas. The wall is actually something to do with a local sport, possibly “jeu de tambourin”, but I’m not quite sure of its function, and the former playing area is now a car park.

by John Q on September 15, 2023

One of the iconic moments in Australian sport occurred in at the 2002 Winter Olympics. Australians are strong in most summer sports, but we don’t have much in the way of a winter, so it was considered quite an achievement for Steven Bradbury to make the finals of the speed skating event. He was given little chance of winning, and was trailing the pack until the final seconds, when all four skaters ahead of him crashed spectacularly. Bradbury cruised past them to claim the gold medal, one of only six in Australia’s winter olympics history.

It strikes me that this is a metaphor for the current position of the EU. It’s long been regarded as an also-ran in the global economy, and geopolitics, trailing behind the US, China and Russia. And (at least 52 per cent of) the UK decided it could do much better outside. The EU has plenty of problems with the climate catastrophe, sluggish economic growth, the rise of the far-right and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

But compared to the crash of the others, it looks pretty good. It’s way ahead on decarbonization, has mostly recovered from the disaster of austerity, and has high living standards and (unlike the US) rising life expectancy. The far-right has had some wins, but nothing comparable to its takeover of the US Republican party. And Brexit has served as an awful warning to anyone contemplating leaving. The problem facing the EU now is how to deal with the queue of eager applicants.

Of course, prediction is difficult, especially about the future. The ECB could screw up again, and generate another long recession. The far-right could do better. On the other side of the coin, the Democrats could win convincingly enough in 2024 to put an end to the threat of Trumpism. But right now the EU seems to be dodging the worst of the global trainwreck.