Well, its very hard not to feel sorry for Gordon Brown right now, but I seem to be managing it. On the one hand, how unlucky to be caught off-guard like that, after being confronted with such unpleasant and ignorant views. There’s a lovely passage in James Cannon’s The History of American Trotskyism in which, talking about the dog days in the early thirties and describing the cranks and nutters who passed through his group, he says something to the effect of (I’m quoting from memory here) “If, despite my unbelief, there is an afterlife I think I will go to heaven, not because of anything I have done, but because oif everything I have had to listen to”, and I often feel sorry for politicians whose job it is to listen to people like that drivel on, even though I know they chose the job. Still, it seems to me there was only one course of action which would have created a chance, however small, of salvaging the situation, which would have been displaying a little integrity and saying, well, something to the effect of what Cannon said. It probably wouldn’t have worked, but the particular way he’s gone about seems to me like just digging deeper.

{ 166 comments }

It’s exciting to see a paper about blogs across the political spectrum that goes beyond the by-now rather common practice of looking at who talks to whom among bloggers (e.g., whether there are any cross-ideological conversations going on). Yochai Benkler, Aaron Shaw and Victoria Stodden of Harvard’s Berkman Center for Internet & Society have just released “A Tale of Two Blogospheres: Discursive Practices on the Left and Right” showing some significant differences in types of blog platforms used (with different affordances), co-authorships and levels of participation among blogs of different political persuasions. Here is one example of specific findings (based on analyses of 155 top political blogs):

Over 40% of blogs on the left adopt platforms with enhanced user participation features. Only about 13% of blogs on the right do so. While there is substantial overlap, and comments of some level of visibility are used in the vast majority of blogs on both sides of the political divide, the left adopts enabling technologies that make user-generated diaries and blogs more central to the site to a significantly greater degree than does the right. (p. 22.)

There are lots of other interesting results in the paper so I highly recommend reading it [pdf].

It’s very clearly written and summarizes related literature well so in case this is not an area you’ve been following, this is a good piece with which to start to familiarize yourself with related debates. If it is an area that you’ve been following then this is a must-read to see some truly original contributions to the literature.

For more on this elsewhere, Ari Melber has an interview with Yochai Benkler on this research in The Nation.

{ 24 comments }

John’s posts have pushed me to write a post that I’ve been thinking about writing for a while – which books are useful for understanding where we (‘we’ here being the left under a reasonably expansive definition of the term) are now, and what possible new directions we might take? I’m putting up this post to learn rather than to dictate, but will list a few books that I think (given my own personal history, values, geographic location etc) are valuable to start the ball rolling. None of these choices will surprise people who have read _CT_ for a while – but they do seem to me to be books that are at the center of a set of interlinked debates that I’ve gotten pulled into over the last few years. Feel free to talk, of course, about other books in other debates (with as much detail about context; why you think these books are important etc).

[click to continue…]

{ 44 comments }

A clarifying (for me) piece by Chris Brooke at the Virtual Stoa, comparing Cameron and Blair:

The reason Blair was far more successful as a centrist politician than Cameron is managing to be is that he went out of his way to humiliate the Left of his party in public as a part of his move to the right. He chose to pick fights that he really didn’t have to fight, with the result that it made it all much easier for former Conservative voters to think that it was safe to vote Labour after all.

Cameron, by contrast, has made a lot of centrist noises, and he’s done various things that the Tory headbanger tendency doesn’t much like (stuff on the website about tackling homophobic bullying in schools, running more women candidates or candidates from ethnic minorities in winnable seats, banging on about the environment, usw), but he’s never seriously tried to stage a meaningful fight with the party’s Right, to lure them out into the open, and to slap them down in public.

{ 40 comments }

The headline Tory education policy is introducing Swedish style school vouchers — basically, making it easy for non-profits to set up schools, and funding them strictly on a per-pupil basis (see manifesto p53). I’ve criticized earlier version of this proposal in the past (as an out-of-the-blue email reminded me yesterday — its nice to know that people read 6 year old CT posts). Swift and I (PDF) wrote a piece recently about the latest version of this proposal, not criticizing it, but offering unsought advice about how to implement it in a way that is most likely to produce some benefits for less advantaged children. When we wrote it, it really did seem relevant to something: right now it seems like something written in another age, to me. Still, in case that age ever returns, I thought I’d point to it for people to consider.

{ 4 comments }

My last post, arguing that the left needed to offer a transformative vision as an alternative to rightwing tribalism has drawn lots of interesting responses, and generated some great comments threads, both here and elsewhere (Some of them: Matt Yglesias,DougJ at Balloon Juice, Democracy in America at the Economist,Aziz Poonawalla at BeliefNet,Geoffrey Kruse-Safford |, and Randy McDonald).

Since my idea was to open things up for discussion, I don’t plan to comment on particular responses. I do want to respond to one theme that came up repeatedly, a combination of discomfort with words like ‘transformation’ and ‘vision’, and a feeling that a politics in which such words are employed is inconsistent with the pursuit of incremental reforms. Even though I stressed the need to learn from such critics as Burke, Hayek and Popper about the need for reform to arise from organic developments in society and to avoid presumptions of omniscience, the mere use of words like ‘vision’ set off lots of alarm bells.

To me, the difficulty of getting this right reflects my opening point in the previous post. After decades of defensive struggle, we on the left no longer know how to talk about anything bigger than the local fights in which we may hope to defend the gains of the past and occasionally make a little progress. But the time is now ripe to look ahead.

My main point in this new post is to reject the idea that there is a necessary inconsistency between incremental progress and the vision of a better society and a better world. (I’ll link back here to my earlier post on Hope, which might be worth reading at this point, for those who have time and interest.)

{ 172 comments }

A Belgian Bishop, “Roger Vangheluwe”:http://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roger_Vangheluwe, has resigned last Friday. He admitted that in the 1970s and 80s he has, for many years, sexually abused a young male family member (a nephew, it seems). According to the newspaper reports, last Monday a family member of the victim wrote an e-mail to all Belgian Bishops informing them about the abuse, which caused Vangheluwe to “publicly confess”:http://www.kerknet.be/admin/files/assets/documenten/Teksten.pdf and to resign.

“According”:http://www.standaard.be/artikel/detail.aspx?artikelid=IP2PDM7C&_section=60732860&utm_source=standaard&utm_medium=newsletter&utm_campaign=krantenkoppen “to”:http://www.demorgen.be/dm/nl/989/Binnenland/article/detail/1097762/2010/04/26/Tientallen-klachten-misbruik-kerk-sinds-vrijdag.dhtml Peter Adriaenssens, a professor in pediatric psychiatry, who is heading a Commission that is investigating the accusations of sexual abuse in the Belgian Catholic Church, this case has triggered about 40 complaints to the Commission of other cases of sexual abuse in the Church since Friday evening. In the last two years there had been about twenty complaints.

Wondering what more will emerge. In Belgium a very large percentage of the population (officially more than 90%) is Catholic; but as I know from personal experience, this need not mean anything. In many cases it is social conformity, or (in the past, at least) primarily an admission ticket to a good school. Any Belgian who thinks this is a good moment to officially quit the Church, can find instructions on how to do so “here”:http://unievrijzinnigeverenigingen.be/nl/Faq/WatBetekentKerkuittreding.html.

{ 123 comments }

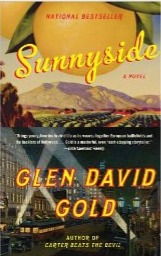

Just before Christmas, I wrote a piece discreetly titled “Sunnyside: Best Book of the Year“. I was surprised that one of the most inventive, funny and profound books I’ve ever read hadn’t made it onto the seasonal glut of ‘Best of 2009’ books. That post elicited an email from no less than Glen David Gold himself. And always with you, gentle reader, in mind, I asked Glen if he’d be willing to take part in a CT book event. He said he would.

Just before Christmas, I wrote a piece discreetly titled “Sunnyside: Best Book of the Year“. I was surprised that one of the most inventive, funny and profound books I’ve ever read hadn’t made it onto the seasonal glut of ‘Best of 2009’ books. That post elicited an email from no less than Glen David Gold himself. And always with you, gentle reader, in mind, I asked Glen if he’d be willing to take part in a CT book event. He said he would.

So here we are, with (northern hemisphere) summer right around the corner and the paperback of Sunnyside due out in the US any minute. In a couple of weeks, I’ll be posting on CT a set of essays about Sunnyside. Some great writers are going to take part. We’ll have Stuart Evers, a writer many of you will know and love from the Guardian’s book review pages; New York comics guy Adam McGovern, the man behind Pood; deadlines permitting, Robert Hanks, who reviews films books and pretty much anything, often for the Independent; and of course Glen himself with an essay in response to all of ours, and plenty of badgering about in the comments.

Consider this a heads up to read that lovely hardback or rush out and buy a copy before the event kicks off. Sunnyside is a terrific read; fantastic fun, tugger of heartstrings, prompter of head-scratching thoughts on the meaning of life. You won’t regret it.

{ 2 comments }

We’ve had a fair bit of fun here lately, pointing out the silliness of those who are supposed to be the intellectual leaders of the right, in its libertarian, neoconservative and Republican tribalist versions. But, as quite a few commenters have pointed out (one using the same, maybe Oz-specific, phrase that occurred to me) the exercise does seem to savor a bit of flogging dead horses.

It seems to me necessary to go beyond this, which was one reason for my post on hope the other day. To make progress, we need to reassess where we stand and then think about where to go next. This is bound to be something of a confused and confusing process. Over the fold, I’ve made some (quite a few) observations, making for a very long post, which is mainly meant to open things up for discussion.

{ 186 comments }

Well?

Listening to the BBC and reading the papers I get no sense of the level of panic that it seems to me that the two major parties ought, it seems to me, to be feeling, nor of whether the pollsters have any idea how to model the sudden change in the LibDem popularity. (Fiddling with the BBC site indicates that the LibDems wouldn’t get many more seats even with 30% of the vote — I find it hard to believe that the designers have really thought out their assumptions beyond a 25% or so showing, which itself would be historic). 6 days in, the poll bump seems not to be going away. I’ve no idea whether the polled support for the LibDems will translate into actual votes or gain them more. Is the apparent absence of panic premised on a good understanding that this is all fake? Or is it just impressive acting?

More or less open thread.

{ 126 comments }

The calendar has once again rolled around to the date on which we commemorate Charles Krauthammer’s “pronouncement”:http://www.aei.org/events/filter.,eventID.274/transcript.asp that:

Hans Blix had five months to find weapons. He found nothing. We’ve had five weeks. Come back to me in five months. If we haven’t found any, we will have a credibility problem.

You’ve had seven years now, Charlie. How’s it looking? Hoping for a result sometime in year eight?

{ 141 comments }

The other week I wrote about a report that a philosopher accepted to an NEH Summer Institute overseas “been given 12 hours to ‘demonstrate’ that she has full-time childcare arrangements for her son for the month of July that ‘are to the [completely unspecified] satisfaction’ of the Institute directors; if she fails to meet this requirement, she has been told her accceptance in the program will be withdrawn.” At the time, it seemed clear that there was no way an NEH-funded operation should be doing this and that, while there was some slim possibility of an explanation that made the whole episode seem reasonable, the Institute director or directors were very much more likely to be completely out of line in making such a demand. Well, guess what?

The National Endowment for the Humanities has apologized to a grant recipient who was told by the director of an NEH-financed seminar in Europe that she had 12 hours to demonstrate that she had adequate child care arrangements in place for her son or she would lose her spot. … An NEH spokeswoman, via e-mail, said Tuesday that the investigation by the endowment determined that the report “was, unfortunately, true. NEH has accepted full responsibility and apologized to the professor involved. We believe we are in the process of resolving the issue to her satisfaction. We have assured her that she is welcome to attend the institute to which she applied and, at her request, we have also extended the deadline to make it possible for her to apply for another seminar if she so chooses.” The spokeswoman added: “Asking an applicant to provide information regarding child care was inappropriate and should have had no bearing on the selection process. Qualified applicants who tell the NEH that they will participate full time in our programs should be taken at their word. We erred and are determined that it will not happen again.”

Good.

{ 44 comments }

[UPDATE: One of the CAP authors, John Halpin, showed up in comments to complain – very reasonably – that I linked to the wrong part of their three part series, and failed to make clear it was part of a series. (I copied it from Goldberg, in composing the post! Why would I assume that anything he does is right?) Anyway, here is Halprin’s response to my post, with links. Halprin also argues that he and his co-author handled some of the stuff I wanted included in part 3. I admit that I had only read parts 1 & 2 before writing the post – I though part 3 was still forthcoming – but it doesn’t seem to me that the material from part 3 he quotes is quite forceful or extensive enough to do the job, even given that it must be done briefly.]

Jonah Goldberg links, approvingly, to a Damon Root post at Reason, complaining about a new Center For American Progress paper entitled “The Progressive Intellectual Tradition In America” (PDF). Root’s complaint is fair, but only up to a point. Here’s the fair bit: the CAP paper is a feel-good affair. Nothing about uglier aspects or excesses of American Progressivism: specifically, racism and sexism, hence eugenics. (And imperialism, but let’s just stick with eugenics for this post.) Of course the obvious objection to that is that there was nothing distinctively Progressive about racism and sexism. It’s just that we are talking about the late 19th/early 20th Centuries here. Still, if you combine eugenics – even if it’s only average for the era – with political philosophy and policy you sure can get bad results. There’s no reason whatsoever to paste this ugly history on every single contemporary formulation of progressive political philosophy. If Barack Obama is giving a stump speech, and he delivers some applause line about progressive ideals, there is no reason for him to pause and add a pedantic footnote about eugenics and how some Progressives, and some people some Progressives admired as scientific authorities, believed ugly stuff a hundred years ago. But if you are writing a history, the presumption is that you want people to learn from history, and some of the major lessons of the Progressive Era are cautionary ones, philosophically and in terms of policy. I doubt the authors of these papers would deny this, so including a ‘cautionary lessons’ subsection would have been a better scheme. (If I had to guess, they’re thinking tactically. ‘If we mention this stuff, being careful to get all the necessary nuance in, someone like Jonah Goldberg will find it and quote it, carving out the nuance, and it will sound like even CAP admits that Progressivism = Eugenics.’ Still, if you are damned if you do, damned if you don’t, you should do the right thing and be damned.)

Now we get to the unfair bit. Root and Goldberg seem to think that if you are advocating progressivism today – rather than writing history – there is some vital need to self-lacerate, early and often, over the whole eugenics-a-hundred-years-ago business. The Goldberg rule seems to be this: if some Progressive believed in eugenics – or if some really major, central figure of the Progressive movement admired someone who was a major proponent of eugenics – then Progressives have to “own up” to this. Goldberg (from the post linked above): [click to continue…]

{ 204 comments }

One reason that many on the left of politics preferred Obama to Hillary Clinton is that his rhetoric, at his best, promised something more than incremental reform, a promise summed up by slogans like “Change we can believe in” and “Yes we can”.

Given the political realities of the US, and the obvious fact that Obama is instinctively a pragmatist and centrist, it was never likely that this would translate into radical policy action in the short run. Still, it seemed at least possible that an Obama presidency would begin a renewal of a progressive project of transformation, setting out the goal of a better world. One respect in which this hope has been fulfilled, for me, is in Obama’s articulation of the goal of a world without nuclear weapons, and in the small but positive steps he’s taken in this direction.

I plan to talk about the specific issue of nuclear disarmament in more detail in a later post. The bigger point for me is that after decades in which the left has been on the defensive, it’s time for a politics of hope. We need hope to mobilise a positive alternative to the fear, anger and tribalism on offer from the right. Centrist pragmatism provides nothing to match the enthusiasm that can be driven by fear and anger, as we have seen.

What the politics of hope means, to me, is the need to start setting out goals that are far more ambitious than the incremental changes debated in day-to-day electoral politics. They ought to be feasible in the sense that they are technically achievable and don’t require radical changes in existing social structures, even if they may set the scene for such changes in the future. On the other hand, they ought not to be constrained by consideration of what is electorally saleable right now.

Over the fold, I’ve set out some thoughts I have for goals of this kind. At this stage, I’m not looking for debate on the specifics of these goals or the feasibility of achieving them (again, more on this later). Rather, I’d welcome both discussion of the general issue of what kind of politics the left needs to be pursuing, and suggestions of other goals we ought to be pursuing

{ 80 comments }

Greg Mankiw suggests that “he has identified the Anti-Mankiw Movement”:http://gregmankiw.blogspot.com/2010/04/anti-mankiw-movement.html. Apparently, it consists of a graduate student who doesn’t like his textbook very much. On the same expansive definition of social movement, I would like to formally announce that I am re-constituting myself as the Pro-Mankiw Movement. Our (or, rather, my) slogan: Let Mankiw Unleash His Inner Mankiw. In particular, “building on previous suggestions”:https://crookedtimber.org/2008/03/04/principles-and-practices-of-economics/ I would like to advocate in the strongest possible terms that Mankiw rewrite his popular textbook so that the relevant sections cover the intriguing case of N. Gregory Mankiw’s domination of the Harvard introductory economics textbooks market.

Since N. Gregory Mankiw returned to Harvard to teach the College’s introductory economics class, 2,278 students have filled his weekly lectures, many picking up the former Bush advisor’s best-selling textbook, “Principle of Economics” along the way. So, what has professor of economics Mankiw done with those profits? “I don’t talk about personal finances,” Mankiw said, adding that he has never considered giving the proceeds to charity. … Retailing for $175 on Amazon.com … Mankiw asserts that “Principles of Economics” has been the bible of Harvard economics concentrators since before he took over “Economics 10.”

Now this couldn’t possibly be an example of a public spirited regulator wisely choosing the best possible product on the market, and imposing it on his regulatees for their own good. As the N. Gregory Mankiws of this world know, such benign autocrats only exist in the imaginations of fevered left-wingers. So it _must_ be a story of monopolistic rent-seeking and regulatory collusion. And what could be more fitting than that these monopolistic abuses be documented in the very textbook that is their instrument!

I’ve suggested before that if I were N. Gregory Mankiw:

I’d claim that I was teaching my students a valuable practical lesson in economics, by illustrating how regulatory power (the power to assign mandatory textbooks for a required credit class, and to smother secondary markets by frequently printing and requiring new editions) can lead to rent-seeking and the creation of effective monopolies. Indeed, I would use graphs and basic math in both book and classroom to illustrate this, so that students would be left in no doubt whatsoever about what was happening. This would really bring the arguments of public choice home to them in a forceful and direct way, teaching them a lesson that they would remember for a very long time.

But this, in retrospect, seems far too lily-livered approach for the true Mankiw. Why not instead use the class as an experimental setting to see how far the price for the book can be jacked up before profits begin to decline? That would give Harvard econ 10 students a practical grounding in economic theory that they could genuinely claim as unique.

{ 59 comments }