In a classic discussion of scientists sampling the ground in the Amazon rainforest, Bruno Latour details the process through which physical bits of soil are turned into recorded measurements and data points for comparison and analysis. He remarks,

Stage by stage, we lost locality, particularity, materiality, multiplicity, and continuity, such that, in the end, there was scarcely anything left but a few leaves of paper. … But at each stage we have not only reduced, we have also gained or regained, since, with the same work of representation, we have been able to obtain much greater compatibility, standardization, text, calculation, circulation, and relative universality, such that by the end, inside the field report, we hold not only all of Boa Vista (to which we can return), but also the explanation of its dynamic.

Now, via Andrew Gelman, a fascinating story from Quirin Schiermeier at Nature about the social production of data.

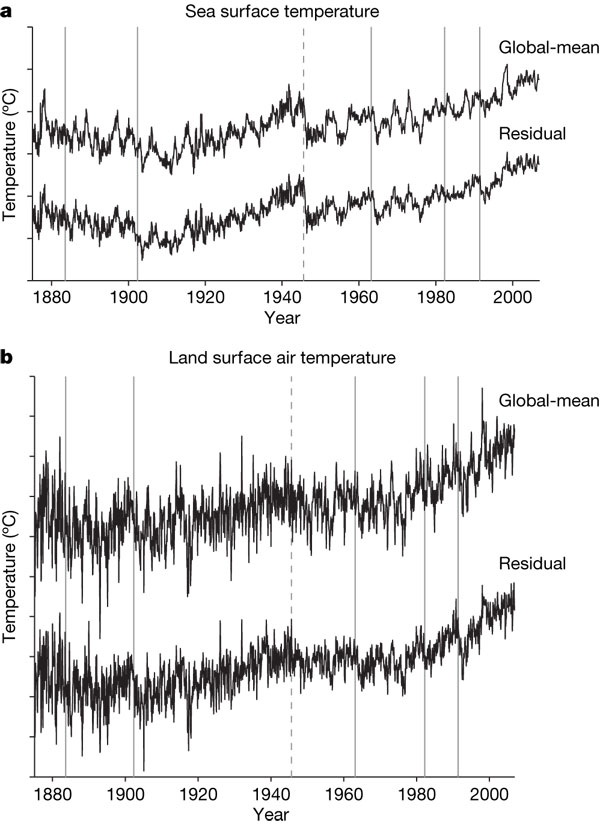

The 20th century warming trend is not a linear affair. The iconic climate curve, a combination of observed land and ocean temperatures, has quite a few ups and downs, most of which climate scientists can easily associate with natural phenomena such as large volcanic eruptions or El Nino events. But one such peak has confused them a hell of a lot. The sharp drop in 1945 by around 0.3 °C – no less than 40% of the century-long upward trend in global mean temperature – seemed inexplicable There was no major eruption at the time, nor is anything known of a massive El Nino that could have caused the abrupt drop in sea surface temperatures. The nuclear explosions over Hiroshima and Nagasaki are estimated to have had little effect on global mean temperature. Besides, the drop is only apparent in ocean data, but not in land measurements. Now scientists have found – not without relief – that they have been fooled by a mirage.

The mysterious post-war ocean cooling is a glitch, a US-British team reports in a paper in this week’s Nature. What most climate researchers were convinced was real is in fact “the result of uncorrected instrumental biases in the sea surface temperature record,” they write. Here is an editor’s summary.

So, what’s the explanation? The post continues:

How come? Almost all sea temperature measurements during the Second World War were from US ships. The US crews measured the temperature of the water before it was used to cool the ships engine. When the war was over, British ships resumed their own measurements, but unlike the Americans they measured the temperature of water collected with ordinary buckets. Wind blowing past the buckets as they were hauled on board slightly cooled the water samples. The 1945 temperature drop is nothing else than the result of the sudden but uncorrected change from warm US measurements to cooler UK measurements, the team found.

And from here it is a short hop back to Latour:

That’s a rather trivial explanation for a long-standing conundrum, so why has it taken so long to find out? Because identifying the glitch was less simple than it might appear, says David Thompson of the State University of Colorado in Boulder. The now digitized logbooks of neither US nor British ships contain any information on how the sea surface temperature measurements were taken, he says. Only when consulting maritime historians it occurred to him where to search for the source of the faintly suspected bias.

{ 117 comments }

DCA 05.29.08 at 10:34 pm

Of course, the question then arises, how much of the

1900-1945 increase came from fewer bucket data, and more from engine intakes? Certainly not much of the 19th century data came from engine rooms. There are a lot of interesting lessons in the graph on Gelman’s blog showing data sources over time.

Megan 05.29.08 at 10:37 pm

At a recent climate change meeting, several high level people in my water agency pondered why one sea level gauge shows sea level dropping in one town in the Bay Area. The rest of the gauges in the state show sea level rise. They talked it over for a good twenty minutes (perhaps the bay has found an adjacent inlet to fill?, perhaps the ground is subsiding? local seismic activity?) before an old hand asked whether anyone has gone out to look at the gauge. No one has, so the conversation was postponed until someone, you know, goes to LOOK at it.

stuart 05.30.08 at 12:00 am

megan, sounds like a very labour intense way of dealing with that problem. A better method that is commonly used is to massively oversample (i.e. put far more gauges that you need to have a statistically sound sample size) and then use statistical methods to throw out any outliers. That way you set them all up once and can automatically filter out a good data set without having to investigate every anomalous reading or location. Faster and cheaper in most situations.

dsquared 05.30.08 at 12:28 am

Of course Kieran is kidding here; I have recently discovered from “Standpoint” magazine, or perhaps from Richard Dawkins, that Bruno Latour is French and furthermore a sociologist of science. And therefore that nothing he says can possibly be taken seriously. If anyone disagrees with me, I will invite them to step out of the window if they don’t believe in Newton’s theory of gravity. And then chuckle to myself about how clever I am, possibly while leafing through Martin Gardner’s hilarious latest collection of articles.

that’s a joke, btw.

marcel 05.30.08 at 12:52 am

Dsquared wrote: Bruno Latour is French…

Are you sure that he’s not Freedom? If so, we should probably take him seriously.

vivian 05.30.08 at 1:33 am

A similar thing came up earlier in the sea-surface temperature measurement. They used to take the measurements with canvas buckets (they fold up in confined spaces, like ships), and there was evaporation from the whole bucket surface. At some point they switched to nonporous buckets. Reginald Newell would tell this anecdote as he ran his sea-surface temperature animation back in the early nineties. It was a good talk – you’d see the Suez and Panama canals open, and suddenly there would be no measurements around the long coastal routes. Wars disrupted measurements too. (Really sweet person, too, often visited my boss but always had time to chat and teach me something or another.)

e julius drivingstorm 05.30.08 at 4:05 am

Navies typically take bathythermograph readings down to great depths. Most often the sea surface temperature is isothermic down to certain depths in certain regions. At a point perhaps 20 to 1000 feet down the temperature gradient breaks sharply negative indicating a suddenly much colder temperature.

It would be interesting to see if warmer sea surface temperatures are accompanied by deeper isothermic layers. Someone must be correlating such data I suppose.

rcriii 05.30.08 at 10:53 am

I can tell a similar story. On one of our vessels the crew refused to turn the pump engines full speed, citing oil temperatures as evidence that the engines were working at full power. This contradicted our engineering models that indicated that the engines were not at full power.

Upon investigation, we discovered that the oil temperature taps were on the oil outflow pipes, while the limit temperature that the crew was citing was for the incoming oil. Voila, we had our power available.

Ken 05.30.08 at 12:13 pm

Clearly the context and methods used to measure things matter. Thanks heavens Bruno Latour discovered this, otherwise engineers and scientists might have wasted valuable time. Hats off to Bruno.

ajay 05.30.08 at 12:31 pm

4: some people can be funny without being offensive, and some people can be both funny and offensive. I would recommend either group.

Kieran Healy 05.30.08 at 1:04 pm

Clearly the context and methods used to measure things matter. Thanks heavens Bruno Latour discovered this, otherwise engineers and scientists might have wasted valuable time. Hats off to Bruno.

See, this is the usual response to stuff like Latour’s — “But we know this already!” — and to some degree we do. But then stories like this come along showing that, even if we’re supposed to know it, we also forget it all the time.

Steve LaBonne 05.30.08 at 1:05 pm

Not really fair, Ken. He didn’t claim to have “discovered” that; he’s explaining how it works, primarily to an audience that really doesn’t know. All the stuff of Latour’s that I’ve read has been sensible and well-informed,and sometimes genuinely illuminating. I think he catches undeserved flak from people who ignorantly lump him in with certain people (not the majority by any means, but prominent enough to be dismaying) in the STS world who are neither sensible nor well-informed.

Steve LaBonne 05.30.08 at 1:05 pm

Kieran was too quick for me!

Ken 05.30.08 at 1:11 pm

I wasn’t criticising Latour – I don’t know enough about him to do that. I was just distrusting the apparent suggestion that the case cited demonstrated anything other than the self-correction that is supposed to be part of the scientific method.

Ken 05.30.08 at 1:16 pm

I may also have been reacting to dsquared’s bizarre post at 4.

John Emerson 05.30.08 at 1:49 pm

I have found that if I throw out the outliers, not only do I save labor, but I also find at some point that my theory is correct.

dsquared 05.30.08 at 1:56 pm

10: with sickeningly inevitability, I find myself responding “ahhh stick it up your ass”.

Latour was a major target of Sokal & Bricmont and has always been one of the chief betes noires for that kind of annoying self-styled “rationalist” who believes themselves to be fighting the heroic fight for the very values of the Enlightenment by sneering at work that they visibly don’t understand (strangely, these types are often surprisingly absent when it comes to having a go at global warming denialists, Lancet hacks or anyone else who might fight back). People like Dawkins deserve to be mocked regularly and as offensively as possible for contributing to public ignorance about science by pretending that it can’t be studied as a sociological phenomenon, particularly if they have actually been appointed to jobs as Professor of the Public Understanding of Science.

As for the “funny” part of that, I guess we’ll just have to wait for the publication in the Reader’s Digest of the numerous humourous anecdotes you have no doubt submitted for consideration.

Righteous Bubba 05.30.08 at 2:06 pm

But then stories like this come along showing that, even if we’re supposed to know it, we also forget it all the time.

People make mistakes, huh?

Ken 05.30.08 at 2:12 pm

dsquared’s transformation into Bizarro Nick Cohen continues…

John Emerson 05.30.08 at 2:17 pm

Could someone explain what’s wrong with what Dsquared said?

Oh, wait. I’m a troll. Cancel that.

Steve LaBonne 05.30.08 at 2:28 pm

Ken, FYI dsquared made a pretty accurate parody summary of some of the more naive and ill-informed combatants on the side of “reason” in the tedious “science wars”. Evidently you’re not familiar with that stuff, to which I can only say “lucky you”.

Henry 05.30.08 at 2:42 pm

In fairness, Sokal himself has been quite “up front”:http://www.physics.nyu.edu/faculty/sokal/mooney-sokal.html in attacking global warming denialists and the like. I suspect that in hindsight, he’d have done things differently.

Ken 05.30.08 at 2:49 pm

I certainly wasn’t aware that Dawkins had said anything about Bruno Latour or drawn any conclusions about him based on nationality, but since this is “pretty accurate parody” it may be so. I thought this must have been one of those North London dinner party conversations so famed in song and story.

Keith M Ellis 05.30.08 at 2:50 pm

“10: with sickeningly inevitability, I find myself responding ‘ahhh stick it up your ass’.”

Which is why you’re more a troll than a blogger, sadly even here.

“Ken, FYI dsquared made a pretty accurate parody summary of some of the more naive and ill-informed combatants on the side of ‘reason’ in the tedious ‘science wars’.”

Yes, in the most obnoxious and provocative manner possible. This would never be tolerated by a mere commenter and certainly “stick it up your ass” wouldn’t be.

Davies can of course write what he likes when he only has to answer to himself. But CT has always been better than this, though Davies has always exhibited these tendencies. Yet he’s gotten worse over time, and this particular example is egregious.

Matt McGrattan 05.30.08 at 2:53 pm

re: 17

I may be misremembering, I haven’t read the book since shortly after it came out, but I don’t remember sociology of science or STS being a particular target of theirs. There is a chapter on Latour, yes, but is he really one of their major targets?

John Emerson 05.30.08 at 2:58 pm

Food fight!

Speaking as a troll, I frequently find Ellis’s hyper-rational tunnel vision highly offensive. This is the guy, if I remember correctly, who argued at DeLong’s site that Krugman destroyed his reputation by writing for the New York Times.

eudoxis 05.30.08 at 3:13 pm

he novelty here is the discovery of historical practices about record keeping and instruments during and shortly after the war.

At least, I hope that instrumental bias is not a unique discovery worthy of a Nature publication 20 years after the specific bias was reported in a meteorological paper.

T.P. Barnett, in a paper published in 1984,

explains that instrumental bias accounts for shifts in sea surface temperature data.

“The SST observations have been contaminated by a systematic conversion from bucket to injection measurements. The bias so introduced may constitute as much as 30 to 50% of the observed change in sea surface temperature since the turn of the century.” (AMS 122(2),303-312)

Latour, even with his irritating powerpoint prose style, would certainly have something useful to say about data comparisons over long time periods like the databases of global temperatures. Likewise, about meta analysis, where researchers combine data from disparate studies to come to a consensus conclusion.

Sebastian 05.30.08 at 3:17 pm

“Yet he’s gotten worse over time, and this particular example is egregious.”

As you gain power, even localized and in little bits, you are more and more free to exercise whatever vicious nature you may have.

John Emerson 05.30.08 at 3:21 pm

Dsquared is a blogospheric monster of cruelty, the way he throws his enormous weight around, heedlessly leaving the crushed bodies of his victims behind him on the path.

dsquared 05.30.08 at 3:25 pm

25: Matt, surely if there’s a chapter all about him (and there is), then he’s one of their major targets by definition? They also had a big face to face debate with him at the LSE.

I note with amusement that between them, the authors of posts 10, 15 and 24 have managed to come up with a bucketload of personal insults aimed at me, and precisely one actual argument; ken’s 9, which was itself a rather laboured piece of sarcasm and which promptly had to be withdrawn as the author admitted he didn’t know what he was talking about. Rationalism really isn’t what it used to be.

Gdr 05.30.08 at 3:29 pm

Latour is rightly mocked by Sokal and Bricmont in Intellectual Impostures for his 1988 paper “A relativistic account of Einstein’s relativity” in which he demonstrates a complete failure to understand the theory of special relativity.

John Emerson 05.30.08 at 3:30 pm

Rationalists are savage as weasels if you push them to the wall.

Righteous Bubba 05.30.08 at 3:35 pm

Dsquared is a blogospheric monster of cruelty

Is this the bucket measurement?

Ken 05.30.08 at 3:36 pm

I didn’t “withdraw” what I said. I just tried to clarify that I wasn’t criticising Latour, though I can see how a determined misreading could have arrived at that impression, so no harm done.

Keith M Ellis 05.30.08 at 3:44 pm

“Dsquared is a blogospheric monster of cruelty, the way he throws his enormous weight around, heedlessly leaving the crushed bodies of his victims behind him on the path.”

It’s not really the point whether anyone is really hurt by what he writes. The point is that there are standards of civility here and he notably deviates from them. In doing so, he’s being hypocritical and by association all the bloggers here are tainted by the hypocrisy. The writers can remove their standard, or insist that one of their own conform to it.

That’s one problem.

The other problem is simply that CT has been generally a nice respite from this sort of crap which so infests the rest of the blogosphere. It’s nice to come here and read this sort of post without having to deal with the typical sarcastic partisan sniping that turns everything into middle-school dominance games. Every topic doesn’t have to be an opportunity to ridicule and/or provoke someone.

I’ve been reading CT and commenting here since it begin, something like the sixth post. It’s still relatively high quality, but there’s less earnest, respectful discussion and more sniping than there used to be. And Davies, more than any other writer here, is all about the sniping. Also, it’s not just unpleasant, it’s banal.

“I frequently find Ellis’s hyper-rational tunnel vision highly offensive. This is the guy, if I remember correctly, who argued at DeLong’s site that Krugman destroyed his reputation by writing for the New York Times.”

Yes, I did argue something approximating that.

More precisely, I argued that Krugman was more valuable as an academic researcher than as a columnist because I believe the actual value of any media opinion writer is negligible. I recall you being very upset over this contention, you thought that Krugman and the like wield great influence. I think mostly they all preach to the converted. I enjoy his BushCo hatred as much as anyone, and I appreciate his fearlessness. But I don’t think it amounts to much. But as a very highly regarded economist, I think his work mattered and that’s where his energies should be spent.

Finally, wouldn’t you agree that sharing a page with the others who occupy the space at NYT where Krugman appears very well might ruin someone’s reputation? Brooks? Friedman? Dowd?

Righteous Bubba 05.30.08 at 3:51 pm

The point is that there are standards of civility here and he notably deviates from them.

Is this not some mirror of the post above? The particular statement you’re complaining about seems to me to be a wholly good-natured joke that you’re not getting.

John Emerson 05.30.08 at 3:53 pm

Yes, I think that the NYT editorial page, which is absolutely uninfluential in exactly the same way that I am, should be givenover entirely to the worst of the worst. Krugman should be replaced by Glenn Beck. Because, after all, as Marx and the astrologists have shown, history and politics are completely governed by inevitable occult forces, and human will influences nothing at all.

CT and DeLong have both improved greatly since the nests of the deadender trolls was cleaned out.

Keith M Ellis 05.30.08 at 3:54 pm

“I note with amusement that between them, the authors of posts 10, 15 and 24 have managed to come up with a bucketload of personal insults aimed at me, and precisely one actual argument…”

You’re mistaken in your assumption that I had any particular quarrel with the substance, such as it was, of your ironic comment. My argument was with its style and, really, why it needed to be made in the first place. Were the comments besieged by people attacking Latour? Was the subject of Kieran’s post itself the “science wars” in which you so eagerly felt the need to throw a volley? Really, was there any real point to your making that comment than to indulge your need to be sarcastic and provocative?

And, you know, there was an actual argument in my contention that your comment was inappropriate. In your assumption that, yes, you found the enemy you were looking for with your comment you seem to have invented “personal insults” in my comment and elided the argument that did, in fact, exist. It just wasn’t the argument you wanted to have. That’s pretty much the very nature of trollish behavior on the web.

At any rate, I find this sort of thing tedious, and especially so arguing the point with you, who will no doubt find some sarcastic retort available in response. I’m not going to pursue it further, I think the point has been adequately made.

dsquared 05.30.08 at 3:57 pm

must … resist … temptation … to say

st..

sti…

stiii …

NO! GET BEHIND ME SATAN! I AM HENRY JEKYLL!

dsquared 05.30.08 at 3:58 pm

just for the record, calling someone a “troll” is a personal insult, HTH.

Keith M Ellis 05.30.08 at 4:06 pm

Well, one last bit…

“The particular statement you’re complaining about seems to me to be a wholly good-natured joke that you’re not getting.”

I’m aware of the context, I just don’t see how it had very much to do with this post. Other than provoking the people that Davies intended to provoke and, as we can see, did. His comment was obliquely related to the post. That is to say, it was an opportunity. And before I complained about it, there were already several comments and exchanges—or rather, feuding arguments—going on in response to it. It has hijacked the thread. It would have done so without my comment.

And I wouldn’t have said anything about #4 alone. It was the “ahhh stick it up your ass” of #17 which really sort of amazed me in its brazenness. #10 was the sort of response Davies knew he’d get from someone offended by his comment…and while it was insulting, at least it was subtle and gentile.

Not that I particularly agree with the school of thought that says you can act like an ass as long as you are sufficiently clever and subtle about it. But you have to admit, that’s the sort of thing that pretty much no one objects to around here. “Ahhh stick it up your ass”, though, tends to result in devoweling.

Matt McGrattan 05.30.08 at 4:06 pm

re: 30

Perhaps it’s just a reflection of my own personal prejudices and interests that I remember Lacan, Kristeva and the like as much more central targets.

dsquared 05.30.08 at 4:10 pm

st ..

st (smack!)

stiiiiiiiiii ….

Walt 05.30.08 at 4:16 pm

Great, now keith has driven dsquared crazy. We’re in for months of “stiiiii”.

I thought dsquared’s comment was on-point, simply because generally Latour is held up as an exemplar of everything that’s wrong with Science Studies.

Matt Weiner 05.30.08 at 4:27 pm

I certainly wasn’t aware that Dawkins had said anything about Bruno Latour or drawn any conclusions about him based on nationality

I just found a review by Dawkins of Sokal and Bricmont. It attacks “fashionable French ‘intellectuals'” and mentions Latour by name.

I don’t know Latour’s work so I can’t say firsthand whether Sokal and Bricmont are being fair to him, though I know the physicist David Mermin has defended parts of the article gdr mentions; IIRC he was inspired partly by his daughter explaining some of what Latour was up to (we went to college together which is why I remember that). Unfortunately I can’t find a free link to Mermin’s original Physics Today piece.

Gdr 05.30.08 at 4:41 pm

Mermin’s 1997 “What’s wrong with this reading?” is behind a paywall here. In it, Mermin agrees with Sokal and Bricmont that Latour’s paper contains “many obscure statements that appear to be about the physics of relativity, which may well be misconstruals of elementary technical points”.

Ken 05.30.08 at 4:44 pm

Thanks for that Matt. The bit of it that mentions Latour says “Sokal and Bricmont expose Bruno Latour’s confusion of relativity with relativism”. Wow – the full extent of Dawkins’ anti-intellectualism is only now being brought home to me…

John Emerson 05.30.08 at 4:52 pm

Mermin gave qualified approval to part of what Latour said. The response:

Yet Physics Today published three angry letters to the editor. Every one of them took up my quotation from Latour. The first said that statements like Latour’s “are thick upon the ground.” It took the phrases I praised to be banalities. The second said that Latour’s phrases were mistranslations from Einstein’s German. It took the phrases I praised to be wrong. The third said that “When Mermin praises Latour for asserting that in relativity ‘Einstein takes the instruments to be what generate space and time,’ the science wars have already been lost.” It took my praise of Latour to be the end of civilization as we know it.

We’re getting far afield, I thought Bricmont’s criticism of Prigogine was excessive. There are some real problems with Prigogine, and his book did have in introduction by Toffler, but in many respects “Order out of Chaos” was illuminating and true. Specifically, it showed why the frequent assertion (by physics-oriented thinkers) that time is reversible and migh someday go backwards is not really true. Second, it said that predictivity is often unattainable. These are hardly New Age idea; they’re commonsensical, and temporal reversibility and the assumption of predictivity are fantasties. But Bricmont acted as though Prigogine were the fantasist.

Righteous Bubba 05.30.08 at 5:19 pm

We’re getting far afield

Well back to the post then. As one of the dumber commenters here I still don’t understand what Latour’s insight is supposed to be in reference to the subject matter above. That he collects stories similar to the ocean-cooling story is commendable, but that such errors exist is not surprising and pointing them out is not insight. Is it? I get harangued by my IT department about garbage in/garbage out alla time.

dsquared 05.30.08 at 5:26 pm

the point isn’t that the errors are made, but the set of social and political conditions which prevented this particular error from being spotted for so long. Latour’s contribution here is that he’s really good at explaining how “scientific facts” are made. When the social entities called “scientific facts” happen to correspond to the actual physical facts, then nobody notices that they aren’t actually identically the same things. Which is why cases like this, where the “scientific fact” of the 1945 temperature drop didn’t correspond, are so interesting, because of what they teach us about the social activity called “science”.

But, to expand on my #4 above, whenever you try to seriously discuss this, you can generally rely on some chucklehead or Martin Gardner fan turning up, misunderstanding everything and accusing you of believing that “scientific facts” are “socially constructed” and making hilarious remarks about tenth floor windows. At which point, I would argue that a sensible social convention would be to request that they stick it up their ass (because the chance of a sensible discussion is minimal). But apparently that last one is controversial.

Matt Weiner 05.30.08 at 5:29 pm

Ken, I didn’t say this earlier, but I found that link because it was the first Google hit for “Dawkins French philosophy.” And it contains an endorsement of a blanket attack on (a group of) French intellectuals in general and Latour in particular. Some other quotes:

“Suppose you are an intellectual impostor with nothing to say, but with strong ambitions to succeed in academic life….”

“This calls to mind Peter Medawar’s earlier characterization of a certain type of French intellectual style….”

“In particular, how shall we know whether the modish French ‘philosophy’, whose disciples and exponents have all but taken over large sections of American academic life, is genuinely profound or the vacuous rhetoric of mountebanks and charlatans?”

This is a wholesale dismissal of the French philosophers discussed, including Latour, in terms specifically directed at their Frenchness. So d-squared’s parody of Dawkins is eminently fair. And when you said “I certainly wasn’t aware that Dawkins had said anything about Bruno Latour or drawn any conclusions about him based on nationality,” it’s because you didn’t spend thirty seconds Googling. I don’t think you’re doing very well as a defender of intellectual standards here.

Nobody seems to be contesting that Latour’s work described here is worthwhile (well there’s comment 9, but that’s been taken care of); perhaps those who do dismiss Latour out of hand are making a mistake? I don’t know whether that includes Sokal and Bricmont (though the suggestion that they only criticize Latour’s article on relativity is false; they apparently spend pp. 92-99 attacking Science in Action); if someone is aware of a place where they discuss the merits of work like what’s mentioned in the post, I’d be interested in it. Even if Latour’s piece on relativity were entirely without merit, it wouldn’t mean that his other work could be dismissed; no one ignores all of E.O. Wilson’s or Noam Chomsky’s work just because they sometimes say something asinine.

Seth Finkelstein 05.30.08 at 6:12 pm

dsquared, as a Martin Gardner fan myself (without, sigh, agreeing with every word he’s ever written) with strong tendencies to exactly the reaction you deplore, let me say I don’t think the chances of sensible discussion are quite as bad as you assume. The trick is not to give off the signals that engender assumptions that, to summarize very briefly for a comment box, everything is about social power and politics. That is the cultural divide.

By the way, I suspect there’s a lot of opening for alliances and understanding over climate denialism – many techies seems to be getting a real political education from that issue.

PJ 05.30.08 at 7:02 pm

I’ve only read ‘Laboratory Life’ (because people said that it is the empirical groundwork on which ‘Science in Action’ is based) and, while it isn’t nonsense, it doesn’t seem to say much which is particularly profound, or even interesting.

It reads fairly accurately as a description of labwork, which might be interesting to someone who doesn’t know about it, but, probably because it never asks _why_ various things are done, it comes across as pretty superficial (and a bit mock naive). If all we get from it is that science is done by people, and is thus unavoidably a social activity, then he hasn’t really added anything over and above the fundamental starting point of science studies.

PJ 05.30.08 at 8:08 pm

Also – I’m not sure that this particular story has much to do with Latour’s work – differences between studies being the result of different methodology seems very much the stuff of everyday science, whereas with Latour we ought to be talking about ‘black boxes’ and ‘actor network theory’.

An interpretation more in line with Latour might be the denialist point of view regarding why the scientific establishment now holds that we can explain away this inconvenient discontinuity.

bob 05.30.08 at 8:13 pm

Matt: in #45 you say “I just found a review by Dawkins of Sokal and Bricmont. It attacks “fashionable French ‘intellectuals’†and mentions Latour by name.”

But Bricmont himself is French – well, Francophone Belgian – and an intellectual (just not ‘fashionable’?). Dawkins doesn’t really attack French per se, does he?

lemuel pitkin 05.30.08 at 8:38 pm

then use statistical methods to throw out any outliers

Do people really do this? Seems like a terrible idea — there’s a lot of information in the outliers. Not to menthion the inconsitency between using OLS or some other estimator that gives more weight to larger errors, and giving zero weight to the largest errors.

Marc 05.30.08 at 10:11 pm

Well, I cracked open my Gross & Levitt (Higher Superstition) to see what they had to say about Latour. I trust that this might be a useful proxy for why scientists have so little use for him; check pages 57-62 if so inclined. One very serious critique that they make, simply put, is that he just doesn’t understand the scientific subjects that he is studying. When discussing relativity theory, understanding (at some level) what is actually is based on and how it is derived actually matters.

The more basic argument is whether the cold, stubborn facts of the world as it is determine the outcome of scientific disputes. This would be the Sokal side of matters; Latour would emphasize instead the role of social networks and power in establishing dominant narratives. Here is his Third Rule of Method:

“Since the settlement of a controversy is the Cause of Nature’s representation, not the consequence, we can never use the outcome – Nature- to explain how and why a controversy has been settled.”

Now, when pressed, Latour would admit that, say, a flat and spherical earth aren’t just competing narratives. But it’s pretty easy to see how passages like the above could be read that way.

More to the point, the climate change issue is a perfect example of why the practical consequences of an approach like that of Latour can be so toxic. Creationists and Global Warming deniers rely heavily on the idea that the scientific consensus is determined solely by power and ideology. The subtle arguments of the academic left are now routinely employed as tools by reactionary forces, and this has made it far, far more difficult to recognize and correct severe environmental damage. By contrast, a public policy debate that is based on, say, whether human activity is actually changing the climate is more productive. The Latours of the world prefer to make it all about social constuction, ensuring that the public won’t accept a referee, such as the scientific method, as the ultimate arbiter of how things work.

This is a major reason why scientists like me have such visceral contempt for the pomo crowd: their word games and academic power trips have had real-life consequences.

Righteous Bubba 05.30.08 at 10:27 pm

Note the origin of the phrase “reality-based community”.

J Thomas 05.31.08 at 3:02 am

Marc, try this metaphor. In biology, evolution has some severe constraints. Every multicellular thing that starts with a fertilised egg has to go through a complex development cycle, and it can only evolve in ways that are compatible with that development. The development cycle *constrains* evolution, and things like meiotic drive constrain it more.

Similarly, the social system has a veto on which scientific ideas can be explored, and which are not allowed. As an obvious example, consider the question of differences in intelligence among races. Negative results would be ignored while anything that looked like scientific evidence for differences between races would be used in bad ways. I’m not saying that such studies ought to be funded, I’m saying that we do look at presumed social utility when we consider funding for science. The Pomo people are right that we put constraints on what science can be done. Not that there’s no science left in science, but it does have some constraints.

More to the point, the climate change issue is a perfect example of why the practical consequences of an approach like that of Latour can be so toxic.”

See, you do it too. Surely you would prefer that this sort of research not be funded, because of its bad social consequences.

Creationists and Global Warming deniers rely heavily on the idea that the scientific consensus is determined solely by power and ideology. The subtle arguments of the academic left are now routinely employed as tools by reactionary forces, and this has made it far, far more difficult to recognize and correct severe environmental damage.

Do those arguments actually make much difference? These are people who oppose some scientific research because they fear the social consequences. Their influence dependss on the votes and the spending patterns of the fearful. Does it really matter what arguments they use? You’re either for them or you’re against them, independent of their particular reasoning to justify their fears.

The Latours of the world prefer to make it all about social constuction, ensuring that the public won’t accept a referee, such as the scientific method, as the ultimate arbiter of how things work.

What is the chance that “the public” would accept scientific method as a referee? “First you’ve got to let us do whatever scientific research we want to do, and then we will tell you what the social consequences of our research will be according to science.” Would creationists accept that? Would free-market economists accept it? Would racists or anti-racists? Anti-life or anti-choice? Before you can accept scientific method as an arbiter, you have to *believe* in scientific method. If we could restrict these choices to the believers, it wouldn’t be a problem.

mityaw 05.31.08 at 4:31 am

Here is another story. In the 1970s in Russia some crackpot scientists claimed that if you gamma-irradiate chickens, they lay way more eggs. They even set up an experiment in one chicken farm and indeed it worked. The production went up 3-fold. A committee from the National Academy of Sciences was sent to investigate. After much time and many interviews with those involved it turned out that the effect was real but the causality was not what the scientists claimed it was. The effect was entirely due to the reduction in the rate of egg pilferage by the workers, who were understandably concerned by all the gamma irradiation going around.

Seth Finkelstein 05.31.08 at 4:54 am

I suspect any scientist who has had to deal with getting a grant would not object to the proposition that funding affects what gets studied. And many of those who have to contend with the popular media reporting their research seem to be quite vocal about the social process of science and society. What is the book The Mismeasure Of Man but an extended discussion of these ideas as applied to intelligence measurement, for example?

The Pomo people seem to say stuff that at heart is pretty trivial, but wrap it up in flowery obscurity and no small amount of condescension. Moreover, when it’s pointed out that to the extent there’s any “there” there, it’s basically making trivial points, they can then turn around and claim that means they’ve moved from resistance to acceptance, so were correct all along.

Nonetheless, I don’t think they spawned the wingnut tactics. Truth-is-what-power-says-it-is has a very long history, and needs no deep philosophy behind it.

abb1 05.31.08 at 10:18 am

@60: are you sure this is a real story? It just seems a bit too reminiscent of Bulgakov’s satire The Fateful Eggs to be true.

praisegod barebones 05.31.08 at 12:53 pm

I’m not sure why Latour gets so much stick for not understanding relativity.

It’s clear that no-one regards having read Latour – let alone made a serious attempt to understand what he’s saying as a serious impediment to weighing into a discussion of his views.

You really don’t have to read very much of his work , and certainly not much beyond the paper that Kieran was referring to here, to see that he’s not claiming that the non-social world is irrelevant to fixing the scientific facts.

And its not just ‘if he’s pushed’: one of the key points in actor-network theory, and something that comes up all over the place in books like ‘The Pasteurization of France’, is the idea that the material world (or eg the microbes) need to be regarded as actors too.

If there is anyone who holds a view according to ‘the scientific consensus is determined solely by power and ideology’, its probably someone like Barry Barnes or Harry Collins. And Collins turns out to know quite a lot about gravity waves (which is what he writes about).

I’m not a fan of Latour’s. But it would be nice if people could get their heads round the fact that a) not all sociologists of science – and not all French speakers – hold the same views.

Oh – and Bob at 55: I gather that Davies is American or Irish or something. So he obviously can’t be criticising Dawkins and Sokal who are both British, which is pretty much the same thing…

J Thomas 05.31.08 at 1:09 pm

Seth, you can judge that the pomo stuff is trivial, but shouldn’t you actually study their material first? “One researcher’s noise is another researcher’s data.”

I agree their smug attitude tends to feel unpleasant. Ideally somebody would study how attitude and presentation affect acceptance of scientific results, so we could learn how to do that better.

John Emerson 05.31.08 at 4:57 pm

Here’s an example of social networks, etc. Poincare discovered about a century ago that the “three-body problem” is insoluble. This might be thought of as an early anticipation of chaos theory. One of the consequences is that the long-run behavior of a solar system is unpredictable if the solar system has more than two members. This is a pretty revolutionary conclusion, but it made little splash.

In later decades Onsager and Kolmogorov developed these ideas, and they became familiar within specialized areas of physics and math, but the repercussions in the area of general science were few. (Contrast the repercussions of relativity or quantum theory). Only in the sixties or so, with the rise of chaos theory and fractal geometry, did specialists in other fields start to pay attention.

If I am not mistaken, large areas of economics (specifically, Econ 101 taught to hundreds of thousands of students every year) still have not taken these results into accounts, and are teaching things that are almost certainly false. (The founder of fractal geometry, Benoit Mandelbrot, has tried, with only moderate success.)

So there’s been a century-long lag in recognizing the consequences of Poincare’s work. (One might also mention lags in recognizing the significance of evolution and of thermodynamics.)

It’s quite possible that the most aggressively mathematical scientistic of the social sciences is the one furthest behind the curve in this respect. It looks as though it will be another generation before economics is rewritten. (Diana Coyle and Rosser, Collander, and Holt in their books defending the economics profession both recognize that economics is very, very slow to change, and both emphasize that anyone trying to change the profession from within must present his or her ideas very, very tactfully — external criticisms are, of course, ignored right off the bat).

If that’s not social networks, I don’t know what it is. People are still teaching stuff that was disproven a century ago.

John Emerson 05.31.08 at 5:02 pm

On the “reality-based community”, people are wrong to sneer. The Republicans are following Marx on Feuerbach: “The point is not to understand the world, but to change it.” A kind of pragmatism.

Democrats always rely confidently on reality as they understood it, only to find out at crunch time that either they misunderstood reality, or that reality had changed. Thye follow a complacent administrative version of stability science, whereas the Republicans are always looking for little exceptional shifts and niches and soft spots and momentary asymmetries to exploit.

The reality-changer have won, as of right now. President Obama, with the help of a filibuster-proof Congress, will have a lot of trouble undoing as much as half the damage that Bush-Cheney-Rove-Rumsfeld did.

Sefrankel 05.31.08 at 5:09 pm

John Emerson 05.31.08 at 5:11 pm

Scientists are supposedly rational, but the more devout ones always misrepresent what science-studies people say. They cherry-pick the most extreme or erroneous statements of the most extreme representative of the field, and then use that as an excuse to ignore the whole field.

Scientists often have a pious, reverential, or worshipful attitude toward science itself, which makes them incapable of paying serious attentions to descriptions of science which seem capable of wandering off in an unworshipful direction. It’s like Catholics with the Blessed Virgin and the Saints.

abb1 05.31.08 at 5:23 pm

It’s not the Republicans who change the world, it’s the side that has the initiative. It was the Democratic party from the Great Depression and until the Civil Rights Act when they lost the Southern bloc – and the Republican party ever since. And it can change again, although nothing seems to indicate any incoming major re-alignment.

Righteous Bubba 05.31.08 at 5:37 pm

It’s like Catholics with the Blessed Virgin and the Saints.

Not a great analogy as the Blessed Virgin and the Saints are bullshit. I’m not sure if it’s better to be delusional about delusions or about data.

That there is an ivory tower for science, though, is once again obvious. Although dsquared was kind enough to explain to me instead of DESTROYING ME WITH INCIVILITY!!!!!! I still don’t get what Latour’s innovation is. If he’s great at explaining situations such as the example in the post above that’s interesting and nice but it doesn’t seem to warrant either the amounts of love or hate that Latour generates in people.

Matt McGrattan 05.31.08 at 5:47 pm

re: 63

I’m not sure if Collins would count as a crude social constructivist either. I’m definitely not an expert and it’s a while since I read much of this stuff at all, but I don’t think either the ‘Bath’ or ‘Edinburgh’ schools were engaged in the sort of crude constructivist talk that some of their less reflective critics sometimes paint them as being.

John Emerson 05.31.08 at 5:49 pm

It’s not really good to be hysterical and delusional about anything, Bubba.

Righteous Bubba 05.31.08 at 6:10 pm

It’s not really good to be hysterical and delusional about anything, Bubba.

I will take this as a soft one over the plate and say OMG there you pomos go with yer obviousitudinousness again.

John Emerson 05.31.08 at 6:28 pm

Scientists like everything to be laid out explicitly.

Seth Finkelstein 05.31.08 at 6:45 pm

#64/ J Thomas – I’ve been very put off by what I’ve read of them, e.g. the journal issue in which the Sokal hoax appeared. The problem is that Sokal’s hoax showed that in at least one case, these people cannot distinguish between scholarship and deliberate utter gibberish. Right, right, I know, it doesn’t disprove that there’s real scholarship somewhere. But still, that’s a pretty powerful indictment of the field. It leads one to wonder how much else is also gibberish masquerading as profundity.

Righteous Bubba 05.31.08 at 7:00 pm

It leads one to wonder how much else is also gibberish masquerading as profundity.

I graduated, so there’s more. But Pomo or no this is not new either.

Seth Finkelstein 05.31.08 at 7:10 pm

Absolutely. Pomo certainly didn’t invent gibberish masquerading as profundity. But, to connect back to dsquared’s objection at #4, there does seem to be a reasonable basis driving that sort of reaction by Martin Gardner fan types.

John Emerson 05.31.08 at 8:02 pm

Pomo and science studies are two different things. Pomo relies on science studies more than the other way around. Few of the Sokal Hoax targets were in science studies; maybe none.

Keith M Ellis 05.31.08 at 8:33 pm

“The problem is that Sokal’s hoax showed that in at least one case, these people cannot distinguish between scholarship and deliberate utter gibberish. Right, right, I know, it doesn’t disprove that there’s real scholarship somewhere. But still, that’s a pretty powerful indictment of the field. It leads one to wonder how much else is also gibberish masquerading as profundity.”

The problem with this is that Sokal’s hoax didn’t show what you claim. The editor of the journal didn’t pretend to know anything about the physics Sokal wrote about. Because Sokal was a physicist, he trusted that Sokal knew what Sokal was writing about when Sokal was writing about physics.

And the irony is that Sokal, in attempting to write like a pomo, misused and misappropriated a number of terms and generally proved that he didn’t know that much about postmodernism. But the editor gave him a break because Sokal seemed to be making an informed argument about the nature of physics.

The whole episode was a clusterfuck.

I’m a person whose very unusual education fully straddled both the humanities and the sciences. I learned the history of science and the philosophy of science while actually doing a fair bit of science. And a fair bit of philosophy.

And the thing is, I find it very often the case that many non-scientists, when writing about the sciences, have woefully inadequate comprehension of the technical matters about which they are writing. And I find it very often the case that most scientists, when talking about science (both philosophically and as a human institution), are incredibly naive and very ideological, and often simply wrong. Scientists assume that by virtue of being scientists, they know something about science in a deep epistemological sense and in a sociological sense. They usually don’t. And they usually know very little history of science, for that matter, which is quite relevant to these topics.

Furthermore, every academic is very territorial.

So what happens in science studies, both those who practice them and those who argue against them, is that everyone is trespassing in everyone else’s specialty and quite often proving themselves ignorant of something important. This causes outrage, which results in hyperbole, reckless generalization, and mischaracterizations.

My argument with Davies’s comment was that he didn’t wait for someone to come along, drag this thread into this feud, and write provocative, over-generalized comments which put words in other peoples’ mouths. He went ahead and did it himself. And some people were offended and there was some argument.

But the discussion here in the last twenty or so comments proves that people could come here, discuss this, and do so in a productive, non-sarcastic and non-provocative manner. There have been some interesting links, some back and forth, even some rethinking of positions.

The Dawkin piece that was linked is an example of how both sides are right and wrong.

Dawkin’s ridicule of Lacan’s pseudomath is well-deserved, as is the mockery of Irigaray’s claim that the historical privilege of solid mechanics over fluid mechanics is sexist.

On the other hand, his criticism of Baudrillard is far-fetched. As someone who knows something about the math and science terms Baudrillard invokes, I think his statement is meaningful. There’s considerable amount of poetic license—but there’s no indication in that quote that Baudrillard is actually trying to make a rigorous argument involving chaos math and turbulence. His allusion to these things is not contrary to their nature.

Furthermore, I don’t see anything in Dawkins’s CV that provides him with the expertise to be pretending to authoritatively pass judgment on these writers within the context they are writing.

That said, it’s not as if I don’t often lose my patience with the ubiquitous glib invocations of QM, relativity, and Godel by people who clearly haven’t any real competence in these subjects—especially because it’s always the same, banal yet deeply mistaken popular misconceptions of these ideas and their implications, in service to predictable homilies involving relativism. And it’s not as if pomos aren’t some of the worst offenders.

But nobody’s sinless here, as far as I can tell. There’s a certain amount of knownothingism on both sides. I can’t understand how Latour could write extensively about relativity without actually studying it; nor can I understand how critics of Latour can write authoritatively about him without actually having read anything by him. Both sides think they “know enough” to pass judgment.

strategichamlet 05.31.08 at 9:06 pm

“And the irony is that Sokal, in attempting to write like a pomo, misused and misappropriated a number of terms and generally proved that he didn’t know that much about postmodernism. But the editor gave him a break because Sokal seemed to be making an informed argument about the nature of physics.”

Didn’t the Social Text editors claim that Sokal’s article had real merit even after he revealed the hoax?

John Emerson 05.31.08 at 9:25 pm

Jesus, now I have to agree with Keith.

Keith M Ellis 05.31.08 at 9:29 pm

“Didn’t the Social Text editors claim that Sokal’s article had real merit even after he revealed the hoax?”

I’m not sure. It’s been years and I’m working on memory. My statement is based upon what the editor-in-chief, or whoever it was that accepted Sokal’s article, wrote in defense. What I’m recalling may have been written quite a bit after-the-fact. Before I read it, I was pretty firmly on Sokal’s side, but it caused me to rethink the whole episode.

abb1 05.31.08 at 10:01 pm

You, learned fellows, always say that casual invocations of Godel’s incompleteness are “deeply mistaken popular misconceptions”, but is it really true? It seems simple enough for a layman to understand – not the proof, of course, but the general idea and implications. Isn’t it one of those cases when you, guys, are being territorial, making things sound more mysterious than they really are?

John Quiggin 05.31.08 at 11:02 pm

Just a note that Gross and Levitt were really bad on global warming, understating the evidence (which was strong by 1997) and pushing the line that scientists should soft-pedal warnings of worst-case consequences for fear of giving aid and comfort to “eco-radicals”.

Seth Finkelstein 05.31.08 at 11:57 pm

I’ve heard the argument “But the editor gave him a break because Sokal seemed to be making an informed argument about the nature of physics.”. But I’d maintain that argument does not refute the point “these people cannot distinguish between scholarship and deliberate utter gibberish.”. It’s a defense that they should not be expected to be able to distinguish. It’s almost a self-referential parody. In comes an article from An Authority, with the right buzzwords, and .. what? They published it because it was politically expedient, due to the social processes they operate under?

But I think the “both sides” approach misses the key dispute, of how much of the supposed scholoarship is meaningful and non-trivial. Note that has to be estimated to some extent, but there are estimation problems all the time regarding what to pay attention to.

Righteous Bubba 06.01.08 at 12:13 am

Sokal’s rounded up a bunch of the debate here:

http://www.physics.nyu.edu/faculty/sokal/

His response to a Latour article in particular seems both like he misunderstands Latour – from the drift that I get here anyway – and that Latour is Latool.

Keith M Ellis 06.01.08 at 2:52 am

Hmm. You make some good points, Seth, but even with them in mind, I do think that is to some degree a valid defense.

If I recall correctly, it was a special issue of the journal where they had solicited submissions from scientists and others where it was expected that the content might be highly technical. That is to say, this wasn’t the norm, it was an exceptional issue.

Furthermore, the academic culture and peer-review publishing just isn’t set up to deal with deliberate dishonesty. There is a presumption of honesty and good intentions that isn’t so much naive as it is a practical necessity. This is why those who falsify their results tend to get away with it. The answer to that problem isn’t to support rules and institutions that regularly look for dishonesty, because that is unrealistic. The solution is to reinforce the cultural ethos that makes dishonesty unthinkable. That’s why an absolute intolerance of plagiarism at the undergraduate level is so important, for example.

And Sokal violated that essential trust. Sokal violated a fundamental academic tenet—it doesn’t matter that it was to prove a point. Intentional plagiarism or falsified results would prove a point, too, if someone wanted to make one about the failures of peer-review, but that wouldn’t excuse someone for doing it and they would be, rightly, disciplined. Sokal should have been disciplined. He could have made his point, though with less intensity and media coverage, in a legitimate way without deliberately undermining the process. His stunt—and it was a stunt—was designed to cast a pall over an entire type of intellectual activity. His aim was so wide, it’s clearly ideological. And it succeeds only because it relies upon an assumption that the editors should have been looking for an attempt to do what Sokal did.

I say that because I believe that anyone, given the type of opportunity provides by the editors of that journal, could have succeeded in a hoax like this. Anyone can be conned.

“But I think the ‘both sides’ approach misses the key dispute, of how much of the supposed scholoarship is meaningful and non-trivial.”

Does it? Because I’d wager a lot of money that the amount of pomo literary theory and science studies and whatnot that relies upon highly technical scientific theories and facts is relatively a very small portion of the corpus. Yet, the critics are using it to tar the whole range of this type of intellectual activity.

Again, I feel like I’m caught in the middle of this. I entirely agree that the postmodernists have been notorious for basically appropriating every possible variety of human intellectual activity as being within their domain and then discussing any example authoritatively in unnecessarily obfuscated technical language. While I think they have produced some good work and some important insights, I think they exhibit a notoriously high ratio of handwaving among intellectuals.

The problem is, though, that what all these people are often doing—very much including the critics of pomo—is essentially ideologically motivated cultural criticism. They all have a worldview to sell, they all have vested interests. When someone has a worldview they’re trying to sell me, I’ve come to deeply distrust the specific arguments they use in order to do so because there’s almost always distortion.

Righteous Bubba 06.01.08 at 3:15 am

And it succeeds only because it relies upon an assumption that the editors should have been looking for an attempt to do what Sokal did.

From the hoax standpoint, they’re not looking. From the bullshit standpoint, one would hope they were.

Anyway, victim of anti-pomo attacks Harry Collins seems quite readable and reasonable to me. Once again via the Sokal page.

http://physicsworld.com/cws/article/print/1607

Keith M Ellis 06.01.08 at 3:19 am

“You, learned fellows, always say that casual invocations of Godel’s incompleteness are ‘deeply mistaken popular misconceptions’, but is it really true? It seems simple enough for a layman to understand – not the proof, of course, but the general idea and implications. Isn’t it one of those cases when you, guys, are being territorial, making things sound more mysterious than they really are?”

I certainly don’t think so. And I can’t really respond to your challenge until I know what you think the “general idea and implications” of Gödel Incompleteness are.

I mean, I can guess, given how you phrased that. It’s widely represented as being a proof that there is a limit to the formalization of knowledge, usually in the service of supporting the idea of the limits (and failings) of rationalism. Less expansively and more accurately, it’s often presented as being a generalized statement about the limitations of mathematics within the context of mathematics. But that’s an exageration—there’s no reason to believe that Gödel Incompleteness applies to anything other than the family of Gödel Statements.

People like to infer the conclusion that there are whole territories of true statements of all kinds that any given formal system cannot express. But there’s no good reason to infer this. It’s possible, but it’s not what Gödel proved. Gödel only proved something very specific. I don’t mean to downplay the importance of that—in the context of mathematics epistemology of the time, this was entirely unexpected and contrary to a basic assumption. Also, as I understand it, contemporary mathematicians tend to think of Gödel numbering as more far-reaching and essential than what it was used to prove.

God knows I really don’t want to go into the fundamental conflict of worldviews involved in all this—but pretty much it all comes down to a conflict between objectivism and subjectivism, right? Relativity is invoked to demonstrate epistemological relativism. So is Heisenberg Uncertainty. So is chaos theory and complexity theory,and of course Gödel Incompleteness. And in each of these cases, none of them actually support a wide-ranging relativism.

They are each examples of unexpected limits on knowledge within specialized contexts. And, as such, within the historical period in which they arose—which were very to moderately absolutist—they came as cultural shocks. This cumulative blow to absolutism slowly spread beyond the narrow technical subjects to which they applied, and began to influence the whole of science and even popular culture. In the process, each of these results have been grossly over-interpreted to support a fundamental shift in the consensual intellectual comprehension of the universe.

I’m not saying that, in general, this isn’t a good thing. The cultural absolutism this replaced was itself an over-interpretation of specific results that misled researchers and was at the core of (or used to support) a number of notorious cultural and political ideas. But I’m personally of the opinion that the pendulum has swung too far in the other direction. Yet that’s not really the point.

The point is worrying about the integrity of certain specific mistaken ideas that are commonly encountered in popular culture and, sadly, some areas of academics. Being wrong is being wrong, it’s not a good thing.

abb1 06.01.08 at 7:52 am

If Godel’s theorems don’t technically imply inherent incompleteness of knowledge in the general sense, they certainly give a hint in that direction. So, when non-technical people invoke it in a colloquial fashion, I don’t see why this is such a big deal. And, unlike ‘relativity’, you never hear the Goedel’s thing from complete idiots, it hasn’t been vulgarized to that extent.

Keith M Ellis 06.01.08 at 8:09 am

“If Godel’s theorems don’t technically imply inherent incompleteness of knowledge in the general sense, they certainly give a hint in that direction.”

Well, my intuition is that there is some inherent limits to rationalized knowledge and that intuition is based upon the cluster of math and science ideas that I mentioned, as well as some others. So in that sense, I agree with you.

(Note: I’m not a philosopher, nor do I intend to give the impression that I am. But my education and self-directed learning form a basis for this interest and were I a philosopher—and I seriously considered the possibility in the past—this is what I’d specialize in.)

But I think that isolating one particular idea, like Gödel Incompleteness, as sufficient support for this notion is unwarranted. And, typically, people don’t qualify this as you did—that Gödel Incompleteness hints at this idea—they present it as if it demonstrates it and this epistemological assertion is a statement of fact.

Again, it’s important to understand that Gödel Incompleteness doesn’t even assert a wide-ranging characteristic of mathematics, much less “knowledge”. Hofstadter and many others have written about it as if Gödel Incompleteness proves that there are mathematical statements other than the class of Gödel Statements which have the same character. But there’s no reason to assume that. It’s certainly possible, but Gödel Incompleteness doesn’t say this. It only says that one very specially crafted kind of statement has this property for any given formal system. To generalize beyond this in mathematics is a stretch, and to go even farther and apply it to all of rational thought is irresponsible.

Though, like I said, I agree with you that the many numerous similar results like this one in a number of domains of rational thought is very suggestive that there’s a general principle at work.

qcolorado 06.01.08 at 12:24 pm

I love you people! I found you entirely by accident, but you have provided the highlight of my day! I’ve often remarked that web commentary starts out with “That’s an interesting post” and ends up with “You (insert name) are an absolute moron, a monster, a blight upon the human race, and should be dragged out and …” etc. etc. I’m not sure if you are scholars or scientists or what – but in my book you have conclusively proven this to be a univeral human trait unimpaired by intelligence, education, or high-falootin vocabulary! Awesome!

engels 06.01.08 at 12:30 pm

Gödel Incompleteness proves that there are mathematical statements other than the class of Gödel Statements which have the same character. But there’s no reason to assume that

There´s no reason not to.

engels 06.01.08 at 12:34 pm

Sorry: better to say there is no reason to assume otherwise.

engels 06.01.08 at 12:39 pm

And there is a reason (nowhere near conclusive…) for suspecting that certain propositions are undecidable simply in that they have resisted proof for so long.

Marc 06.01.08 at 1:29 pm

Interesting discussion. I really do want to emphasize that the argument that science is primarily driven by politics and ideology is now the central tenent of the religious and corporate opponents of scientific conclusions. People defending their home turf (e.g. pomo theorists) need to keep in mind that the tools which they are talking about are now being used primarily outside the academy, basically to argue in bad faith. They are employed to argue that evolutionism is a religion like all others, and that the consensus of scientists on climate change is driven by ideology and the pursuit of grants. (On the latter point, I’m an astrophysicist whose interests include theoretical solar models. One would think this would make me, and other astronomers, advocate a central role for the Sun in climate change. Essentially none of us do because the data doesn’t support it – and we understand the interaction of light and matter which is the central ingredient in the greenhouse effect. Go figure.) The sociology of science is real, but the underlying power of the scientific method is extremely deep and ultimately quite stubbornly ruthless in discarding misleading paradigms.

More to the point, one of the things that distinguishes talented scientists is precisely the ability to recognize when prior explanations have misled us. I’ve been able to make a decent career by applying insights from field X into field Y. In my field we’ve seen complete overhauls of cosmology (the expansion of the universe is accelerating for an unknown reason) and planet formation (Jupiter-like planets can be close to their parent stars and in bizarre orbits, which was utterly unanticipated.) The primacy of data in shaping the discourse seems pretty evident in astronomy. And the recognition that the frameworks that we construct are subject to drastic revision is very much present at all.

abb1 06.01.08 at 1:38 pm

When you see something out there you can’t explain – assume dark matter.

strategichamlet 06.01.08 at 2:20 pm

When you see something you can’t explain — come up with some explainations anyway and start exploring their logical conclusions.

“expansion of the universe is accelerating for an unknown reason”

For anyone paying attention this is an interesting case study going on right now. In my opinion, acceleration has reached a level of acceptance unwarranted by the data. It also seems, however, that eager acceptance will result in exactly the right kind of increased activity necessary to get the most salient evidence possible either way.

J Thomas 06.01.08 at 3:28 pm

“Hofstadter and many others have written about it as if Gödel Incompleteness proves that there are mathematical statements other than the class of Gödel Statements which have the same character. But there’s no reason to assume that.” keith m ellis

I never looked seriously at Goedel. I had an undergraduate math class where it got asserted that Goedel’s theorm has been proven for every formal mathematical system as complicated as the natural numbers. That sounds pretty inclusive.

But when I checked wikipedia just now, they say there are systems that include the natural numbers as a subset that Goedel’s theorem doesn’t apply to. “The key fact is that these axiomatizations are not expressive enough to define the set of natural numbers or develop basic properties of the natural numbers.” So it isn’t as clear-cut as I thought.

John Emerson 06.01.08 at 4:05 pm

Back to the science studies vs. pomo distinction: people in science studies seldom say that “science is primarily driven by politics and ideology”. They say that the science done by any give science is constrained by the way that science is concretely organized: institutions, hierarchies, roles, prescribed procedures, established goals, and enforced methods, credentialization process, financing, etc. This includes a degree of ideological content and economic interest, but these tend to be particular to science. I.E. scientists generally tend to by more technocratic and rationalistic than non-scientists, and since they derive meaning from science itself they tend to be less engaged in and more detached from such popular identifications as religion or populist nationalism. (I think that this was statistically true even of non-Jewish German scientists 1932-1945, though german science was generally willing to serve the Nazis).

Science studies also argues that the power and success of science comes from social forms rather than “ideas” or “concepts”: publication (rather than secrecy), competition to solve agreed-upon problems, the organization of multi-person laboratories to make complex projects possible, the financing of research, ways of rewarding successful researchers, systematic training of researchers and techs in a common body of concepts and methodologies, etc.

Many scientists do not like science studies either, identifying it with pomo. (Of the supposed pomos, Foucault actually did do science studies of a sort, but not most of the others.) Scientists tend to have an idealist, idelaized, worshipful, and unanalytic idea of how science works.

As I’ve said many times, economics is ripe for the science studies approach, and in the specific case of economics ideology and economic interest are, in fact, major factors.

dsquared 06.01.08 at 4:32 pm

But that’s an exageration—there’s no reason to believe that Gödel Incompleteness applies to anything other than the family of Gödel Statements

Yes there is. Quite apart from anything, what do you mean by “the class of Goedel statements”? If there were some property possessed by all and only all those true statements which weren’t theorems, then you could add an axiom stipulating that all statements of that class were theorems.

In any case, Greg Chaitin has proved (constructively, by example) that there are Diophantine equations which are undecidable in the Goedelian sense – and since the Incompleteness Theorem is equivalent to the insolubility of the Halting Problem, I think it’s pretty difficult to argue that it’s a theoretical curiosum of no practical importance.

Marc 06.01.08 at 4:42 pm

Dark matter is actually a beautiful example, and so is dark energy (the acceleration of the universe.) Both concepts are based on real data, and both were initially controversial. Fritz Zwicky in the 1930s proposed dark matter as an explanation for the rapid motions of galaxies within clusters. However, folks outside the field may not appreciate the numerous tests that have since been made that confirm that there really is matter which is not baryonic (protons, neutrons, electrons). We look at the properties of the cosmic microwave background radiation, which preserves a fossil record of the conditions in the early universe. There were sound waves – which tell you about ordinary matter. There were also gravitational effects on the spectrum, which tell you about all matter. You get different answers, just the same as you get from comparing mass and light measurements. The pattern of elements made in the first three minutes also tells you a consistent story – namely, that there is very little ordinary matter in the universe. You can test with the bending of light (lensing), and you also get consistent answers.

We can similarly test dark energy with structure formation (e.g. when did galaxies and groups of galaxies assemble); properties of the microwave background related to the overall geometry of the universe; and gravitational lensing. Both ideas have taken root because they make sense in such a wide range of contexts, and people tried very hard to make them go away. This is the actual practice of science.

dsquared 06.01.08 at 4:49 pm

Marc: all these tests are actually just establishing the presence of excess mass. “Dark matter” is still a placeholder concept and we don’t actually know anything about it at all.

John Emerson 06.01.08 at 4:56 pm

I did the Tao of Physics / David Bohm / etc. tour about 20 years ago, and the only reasonable conclusion I can come up with is that, while fundamental physics is ontologically fundamental, its behavior is so different than anything at a scale we can experience that the science of fundamental physics is not a good model for understanding anything else.

strategichamlet 06.01.08 at 5:37 pm

@102

The tests Marc mentions do considerably more than just establish the presense of extra mass: they indicate that there is a type of matter which does not interact electromagnetically and is ~ 5x more abundent than baryonic matter.

@101

“Both ideas have taken root because they make sense in such a wide range of contexts…”

This is more true of dark matter than dark energy. I think it is important to stress the differences between them, especially for the public. Both the measurements and the theory behind dark energy are a lot more tenuous.

dsquared 06.01.08 at 6:28 pm

they indicate that there is a type of matter which does not interact electromagnetically

no, I don’t think it can actually be taken for granted that when we find out what it is that the excess mass is attributable to, that it’s going to be similar enough to the other things we call matter that we’re going to say that “it’s a type of matter”.

strategichamlet 06.01.08 at 7:08 pm

You keep referring to “excess mass” as if galaxy rotation curves were the only evidence for dark matter. Recent measurements of the Bullet cluster show that dark matter can be disassociated from baryonic matter. The relative heights of the 2nd and 3rd acoustic peaks in the CMB can not be explained by “excess mass.” We may not know everything we’d like about it, but we know a number of things that it is not (e.g. MACHOs, neutrinos, any but the most perverse MOND theories, etc.) and rather a bit about how it behaves.

John Emerson 06.01.08 at 8:15 pm

It’s The Repressed, right? The Unsayable. The Unknowable, but measurable to a degree, Ground of Being.

Walt 06.01.08 at 9:16 pm

I would say that every popular statement invoking Gödel Incompleteness I have ever heard has been wrong. Even Keith’s statement, made with clearly modest intent, is wrong in key respects. It’s an evocative result, but it’s meaning is fairly technical, and the rhetorical purposes it’s put to outside of mathematics are fairly banal. Yes, not everything can be figured out by pure thought.

Walt 06.01.08 at 9:42 pm

The result you’re thinking of, dsquared, is by Yuri Matiyasevich, Julia Robinson, Martin Davis, and Hilary Putnam. It’s fairly common for classes of mathematical problems to be unsolvable. (For example, there is a completely classification of surfaces and 3-dimensional spaces. It is known that it is impossible to classify in 4 dimensions and higher.)

Akshay 06.01.08 at 9:54 pm

To come back to the topic of the original post (too late!), has weighed in. Apparently the bucket issue was known for years. The latest IPCC report spent a section on discussing it. The Thomson contribution lies in helping to quantify the correction needed.

J Thomas 06.03.08 at 1:20 am

#64/ J Thomas – I’ve been very put off by what I’ve read of them, e.g. the journal issue in which the Sokal hoax appeared. The problem is that Sokal’s hoax showed that in at least one case, these people cannot distinguish between scholarship and deliberate utter gibberish.

Was it a peer-reviewed journal?

There’s a place for journals that aren’t peer-reviewed — like you can usually publish in them faster, which makes a big difference if you’re concerned somebody else might publish similar results before you. But I don’t expect them to do a good job of critiquing research.

I haven’t read the details about Sokal’s scam. But I can imagine similar things that I wouldn’t be impressed by. Say some pomo guy sends a paper to a psychology journal. He announces the experiment he’s done about people doing eye twitches when they’re lying. He gets some sort of more=or-less-boring result and he claims his results are significant at the 0.01 level and so on. And after it’s published in a journal that isn’t peer-reviewed, he announces that the whole thing was a hoax. He made it all up and he just copied the statistical results out of other published papers, his statistics were all garbage but nobody noticed.

Would you suppose from that, that the field of statistics is all garbage and also the field of psychology? Professional statisticians have told me that 90% or more of published papers in psychology have serious flaws in their statistics, but….

Maynard Handley 06.03.08 at 1:21 am

”

God knows I really don’t want to go into the fundamental conflict of worldviews involved in all this—but pretty much it all comes down to a conflict between objectivism and subjectivism, right? Relativity is invoked to demonstrate epistemological relativism. So is Heisenberg Uncertainty. So is chaos theory and complexity theory,and of course Gödel Incompleteness. And in each of these cases, none of them actually support a wide-ranging relativism.

”