I’m in Madrid at the moment for the annual meeting of SASE, the “Society for the Advancement of Socio-Economics ” (the main organization for economic sociologists). One of the panels tomorrow is an author-meets-critics session on Gary Herrigel’s recent book, _Manufacturing Possibilities._ While I won’t be on the panel, I have written a review of the book, which Gary has in turn responded to – both are below the fold. The review and response are also available in PDF form if you prefer to read it that way.

Of course, there’s more to life than stuff with big words aimed at early readers. There’s stuff with few words aimed at early viewers! Here’s a good deal on a nice, quite comprehensive collection of the very earliest silent films, Landmarks of Early Film, Vol. 1 [amazon]. I lectured about some of this stuff in my Philosophy and Film class last semester, because I focused on sf – crossroads of speculation and spectacle. It’s a common critical complaint that Lucas/Spielberg-style special effects blockbusters killed a lot that was great about American cinema, in the 1970’s. Then again, film was industrial light and magic from the start, pioneered by the industrious likes of Edison and Georges Méliès (stage magician). No film could be truer to the authentic roots of the medium than whatever Michael Bay is working on right now. Probably that new Transformers movie or something. Maybe that explains why so many of these early films are boring. But in a fascinating way.

What are your favorite early/silent films? What early cinema do you really, honestly, just love to watch. No grading on a curve or so-bad-it’s-good ironizing. I watched quite a bit of Charlie Chaplin, while I was reading Sunnyside. I liked it, but I didn’t love it. I’ve posted before about loving Dreyer’s Passion of Joan of Arc. I’ve never watched any Buster Keaton; never watched The General, for example. Should I? I love Metropolis but I recently watched Fritz Lang’s Woman In The Moon and didn’t really get into it. It veered between dull and draggy self-seriousness and extreme silliness. Although Fritz Rasp (a.k.a. The Thin Man, from Metropolis) was fun.

Who do you think should get the moon gold, should it exist? Defend your answer. (Maybe that inter-title should be an inspirational poster.)

Pursuant of my previous post, the Wikipedia entry for The Big Orange Splot notes that the book uses big words, as books for 4-8 year-olds go. Yes. Words like ‘baobab’ and ‘frangipani’. This is standard Pinkwater operating procedure. Compare a passage from Irving and Muktuk, Two Bad Bears, likewise officially aimed at the 4-8 set. “FWOP! FWOP! FWOP! Oh no! It is the helicopter! FWOP! FWOP! FWOP! Adieu, Irving and Muktuk. Once again, you have failed to obtain muffins by stealth and subterfuge.” My limited acquaintance with the world of children’s book leads me to believe authors are typically editorially compelled to write much less trisyllabically. Pinkwater, being a big fish in this publishing pond, can get away with it. But surely he’s doing it right. Kids are engineered to pick up language from adults, who frequently talk to other adults, so if you write a bit over kids’ heads, they’ll just learn what ‘subterfuge’ means 5-10 years earlier than they might otherwise. Surely there is no harm in that. Kids find it interesting. What do you think? What are your favorite books for very young children that really pour on the vocabulary, apparently on the theory that little pitchers have big ears?

Quick thoughts in response to Yglesias’ ‘against character’ post. Zoning laws are a perfect example of an area in which it is hard to come up with good, principled, liberal answers – classically liberal, that is – that don’t reduce to absurdity. Richard Epstein philosophizes with a hammer about this, with the air of one delicately operating with a scalpel. Pretty much everything the government does should count as a ‘taking’. For a more winning defense of zoning libertarianism, see Daniel Pinkwater, The Big Orange Splot

[amazon] – video here. It’s interesting that conservatives have never sought to open a permanent culture war front against zoning regulations. It seems like a perfect opportunity for a toxic mix of dog-whistles, pandering to bad actors, and all-around irritable gestures seeking to resemble ideas, while managing to be wedge issues. All this irritation, around a grain of truth, can produce scholarly pearls, such as Epstein’s classic book, which in a certain sense expresses an all-American conservative dream. Because, after all, Yglesias is quite right that it doesn’t make much sense, either in philosophic principle or economic practice, for zoning regulations to be so conservative a lot of the time (in the etymological sense of ‘conservative’, not the American political sense.) Possibly only the fact that Pinkwater’s Plumbean is obviously a Big Hippy has preserved us from an Epsteinian slippery slope, in polemical, culture war practice. Conservatives could do with astroturf Joe the Plumbeans, if only they could find them. Someone who can dump a big orange splot of pollution, while declaiming, like Walt Whitman, “My backyard is me and I am it! My backyard is where I like to be and it looks like all my dreams!” Take that, ‘neat street’ zombie liberal clones! That would substantially confuse the issue, in ways that are really philosophically unresolvable. (Bonus style points if you can somehow connect Plumbean with Pruneyard without looking like you are trying way too hard, as I clearly am.)

Defenders of Epstein will note, correctly, that his view is very nuanced and he wouldn’t by any means say everyone gets to dump whatever toxic splot they want, so long as it’s their land. Quite right! Epstein’s philosophy would give a much more sensible resolution to the ‘nuisance’ posed by the Plumbean case than probably any existing zoning laws in the land. Granted. My point is different. Epstein combines exquisite theoretical sophistication with crude anti-New Deal contrarianism (in my opinion). Given the bottomless appetite for the latter, among American conservatives, it’s interesting that there isn’t a dumbed-down, popular talk radio talking point version of Epstein’s philosophy, minus the intellectually worthwhile bits, in constant circulation. It seems like a missed opportunity for debasing the discourse. Again, maybe it’s just that Plumbean is a Big Hippy. What do you think?

UPDATE: I suppose I should have linked to the Wikipedia summary of the plot. For the busy, executive reader of CT who needs the bullet point version of Pinkwater’s classic children’s picture book.

As promised in my previous post, I’m setting up a separate thread for discussion of my premise that a socialist revolution is neither feasible nor desirable. My own thoughts, taken from an old post are over the fold.

UpdateI’ve updated to link to the earlier post remove an unjustifiably snarky reference to aristocratic sentiment and to include a para from the previous post, on situations where revolutions are likely to turn out well.

[click to continue…]

I’ve mentioned Erik Olin Wright’s Envisaging Real Utopias a couple of times, and I’ve also been reading David Harvey’s Enigma of Capital and Jerry Cohen’s if You’re an Egalitarian How Come you’re so Rich. In different ways, all these books raise the question: what becomes of Marxism if you abandon belief in the likelihood or desirability of revolution[1]? To give the shorter JQ upfront, there are lots of valuable insights, but there’s a high risk of political paralysis.

I plan alliteratively, to organise my points under three headings: Class, Capital and Crisis, and in this post I’ll talk about class

When I was but a callow lad, the Gormenghast novels were among my favorites. Now that I am grown into a strapping, callow man, they are still among my favorites. I do so hope that Titus Awakes [amazon] turns out to be good. It was written in the early 1960’s by Maeve Gilmore, Peake’s wife, and only discovered last year in an attic by their grand-daughter. Gilmore based it on notes and an outline by Peake himself. Here’s a Telegraph piece about the rediscovery.

It won’t be released for a few more weeks, but you can listen to the first bit of the audiobook here. Simon Vance is the reader.

Quite a bit of Peake stuff is being reprinted right now, or has come back in print only in the past few years. Just in the next couple months: Peake’s Progress: Selected Writings and Drawings of Mervyn Peake; Mr. Pye

; A Book of Nonsense

. Poke around if you like Peake. I haven’t checked out Boy in Darkness and Other Stories

yet. My daughters have enjoyed Captain Slaughterboard Drops Anchor, and my vintage copy is rather falling apart. So it’s nice to know new ones are available

.

Let’s discuss our hopes and fears for Titus Awakes.

It’s Bloomsday, or Christmas for intolerable Joyceans everywhere. The Wall Street Journal explains the literary background:

What is it about Joyce’s novel about a day in the life of a fictional Jewish mayor of Dublin, Leopold Bloom, that has inspired an international literary event cum pub crawl cum Halloween parade?

What other Interesting Facts about Ulysses have I been unaware of, I wonder? While I wait for you to enlighten me, I will perform the sacred Bloomsday ritual of genuflecting solemnly before the Poster of Great Irish Writers. You know the one—an obscure bylaw requires it hang somewhere in every Irish bar in America, and certain sorts of pub in Ireland as well. The Great Writers can be classified into various non-exclusive subgroups based on their relationship to Ireland, including “Fled”, “Driven from”, “Disgusted”, “Hated”, and “Drank half”.

I’m doing some intellectual scratching about re: the nature of pictures and pictoriality. I think one of the best philosophy books on the subject is Flint Schier, <em>Deeper into Pictures</em> [amazon]. I’m not up for writing a full review, but, briefly, he advocates what is in effect a rehabilitated version of the bad old resemblance theory (the best refuted of all theories of the nature of pictures!) Here is Schier’s first draft of an account of iconicity. “A system of representation is iconic just if once someone has interpreted any arbitrary member of it, they can proceed to interpret any other member of the system, provided only that they are able to recognize the object represented.” (44) And pictures are icons, in this sense. [click to continue…]

There are plenty of reasons to be gloomy about the prospects of stabilising the global climate, but there are also some promising developments, so I’ve started a series on this topic.

I’ve been meaning to write this post for a while, but Stephen Lacey at Grist (via David Spratt on Twitter) has done much of the job for me, and better than I could have. The crucial point is that the cost of solar photovoltaic electricity has fallen dramatically and is almost certain to fall further. In particular reaching the point where it is the cheapest large-scale alternative to carbon-fuelled electricity generation, and competitive (at reasonable carbon prices and in favorable locations) with new coal-fired power.

This makes for some fundamental changes in the debate over climate change and mitigation, even as it reaffirms the central point that advocates of mitigation have made all along, namely that, with an appropriate policy response, the costs of drastic reductions in carbon emissions will be modest in relation to national or global income.

My weekly treat of the Saturday FT is becoming less and less something to look forward to. It’s not just that the fashion shoots are as gauche as those of newspapers everywhere, or that the odious ‘How to Spend It’ bizarrely channels a middle class aspiring to be hot Russian money in London. Nor that Mrs Moneypenny has irrevocably (i.e. on television) revealed herself as a bit of an empty vessel. Nor, even, that my beloved Secret Agent is running out of things to say about the property-acquiring super rich. (I guiltily admit I loved him more when he was melancholy, and still daydream of fixing him up with a friend.) No, my ability to pleasurably drag out the reading for more than an hour is vexed by the increasingly uninsightful and plain old poor value for money that has begun to mark the fiction reviews.

The increasing Americanisation of the FT now has writers review books by their brothers and sisters in arms. The British tradition of publishing book reviews by people who are real-life critics and not part-time cheer leaders and quarterbacks may be nasty, discomfiting and sometimes unfair to writers – and for this I blame editors – but it gives a reader a much clearer view of the essential question; ‘Is it any good?’. I imagine it’s also costing unsung book reviewers their living as money is thrown at superstar writers at the top of the pile.

Case in point: this week’s review by Annie Proulx of a novel, ‘Irma Voth’, by Miriam Toews. Without the name recognition of Proulx, it’s hard to imagine the review being published anywhere except, perhaps, a town newspaper wishing to fill up space and appear cultural by inviting the doyenne of the local book club to write a little something. [click to continue…]

Like everyone else, I’m glad Ta-Nehisi Coates got a NYT op-ed. Unlike everyone else, I haven’t seen X-Men: First Class yet. (Hey, I like comic books.) But I get the general idea, so I’d like to weigh in on the whole Magneto Was Right issue (part ii).

Thing is: it’s not just Magneto, it’s the government, going back to the first film. Everyone is right except Professor X. [click to continue…]

I liked “Embassytown”:http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/0345524497/ref=as_li_ss_tl?ie=UTF8&tag=henryfarrell-20&linkCode=as2&camp=217153&creative=399349&creativeASIN=0345524497 a lot (which will come as no surprise to long time CT readers). It wasn’t perfect. There is a longish section (between the two-thirds and four-fifths mark) which dragged – it had neither the intellectual pyrotechnics nor the pacing of the rest of the book. But where it is good, it soars, and better reconciles literary ambition and sense-of-wonder headkicks than anything else he’s written. It’s hard to compare with any other book – perhaps the closest is Delany’s _Stars In My Pockets Like Grains of Sand_ in its mixture of space opera and linguistic speculation – but the comparison isn’t very close. The writing is more tamped down and Delany’s perverse romanticism is nearly entirely absent. Perhaps the best way to think of the book is as a kind of hard science-fiction, where the ‘hard’ theory that is being played with is linguistic theory rather than speculative physics (now that I think of it, Mieville’s suggestion that his imagined universe is a ‘parole,’ of the ‘langue’ that is the under-lying meta-universe is an obvious hint in this direction). Mieville is not trying himself to contribute to literary theory – but then, when Alastair Reynolds uses weird bits of information theory to come up with a justification for a cloaking device, he is presumably not doing this for the purposes of peer reviewed science. He’s having fun – and so too is Mieville. Some of the concepts – people literally being incorporated into Language as similes by aliens who _need_ concrete referents to think and to speak – are quite wonderful.

I’m not going to write a review of the book (I don’t think it would be possible to top Sam Thompson’s “excellent piece”:http://www.lrb.co.uk/v33/n12/sam-thompson/monsters-you-pay-to-see for the LRB) – but I do want to point to one interesting resonance between the book and _Iron Council_ (which of course we did a “seminar on”:https://crookedtimber.org/category/mieville-seminar/ a few years back. Since there are spoilers, the rest is below the fold.

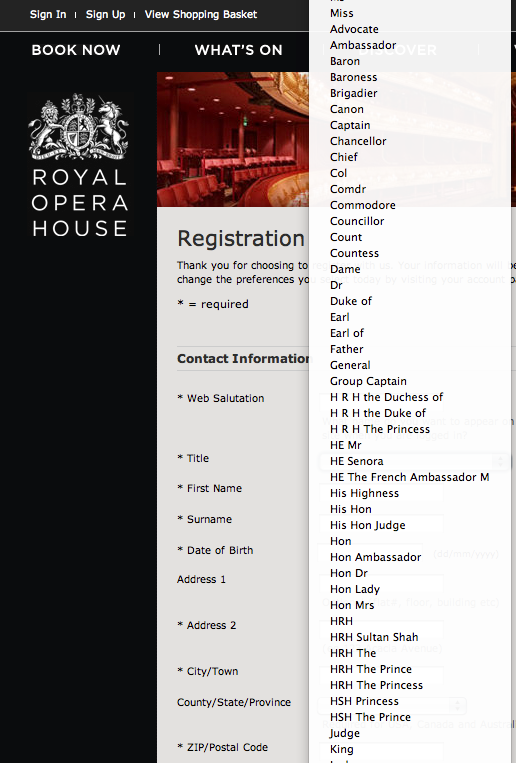

Via Jonathan Davis on the Twitter, the Registration form for the Royal Opera House, which comes with the best drop-down box ever devised. Choose your title! I fear “HE The French Ambassador M” may be taken, however.