If you’ve studied game theory, you’ve probably come across the mixed-motive coordination game, a simple one-shot game in which two representative actors have to figure out how to coordinate so as to find a mutually beneficial equilibrium – but have different interests over which equilibrium they choose. And if you studied it a couple of decades ago, you very likely have heard it referred to as “the battle of the sexes,” a term that has fallen out of common usage, for obvious reasons. But when I read Tyler Cowen’s short piece on the actual historical struggle between women and men for recognition, I was immediately was reminded of Jack Knight’s argument, based on mixed-motive coordination games, for why power is more important to the emergence of social rules than most economists think.

Tyler’s brief claim is as follows:

It’s interesting to think of Mill’s argument as it relates to Hayek. So Mill is arguing you can see more than just the local information. So keep in mind, when Mill wrote, every society that he knew of, at least treated women very poorly, oppressed women. Women, because they were physically weaker, were at a big disadvantage. If you think there are some matrilineal exceptions, Mill didn’t know about them, so it appeared universal. And Mill’s chief argument is to say, you’re making a big mistake if you overly aggregate information from this one observation, that behind it is a lot of structure, and a lot of the structure is contingent, and that if I, Mill, unpack the contingency for you, you will see behind the signals. So Mill is much more rationalist than Hayek. It’s one reason why Hayek hated Mill. But clearly, on the issue of women, Mill was completely correct that women can do much better, will do much better. It’s not clear what the end of this process will be. It will just continue for a long time. Women achieving in excellent ways. And it’s Mill’s greatest work. I think it’s one of the greatest pieces of social science, and it is anti-Hayekian. It’s anti-small c conservatism.

Tyler frames the dispute in a Hayekian way. Unpacking his argument (I think this is right, but am happy to listen to corrections), the Hayekian perspective is that we want information that will allow people to coordinate productively. Hayek suggests that this information is most likely to guide outcomes in “spontaneous orders” like the market, where people can figure out, without very much external constraint, what the rules of interaction ought to be. Better rules will emerge through an unguided evolutionary process within a broader constitutional order, whose main function is to guard against forces that might disrupt this spontaneity.

Tyler points out out that this Hayekian framework is missing something big with respect to gender relations. Spontaneous orders have historically involved a lot of discrimination against women, who are physically weaker than men, and less able to defend their interests. J.S. Mill argued, on the basis of a non-Hayekian rationalist logic, that women would be able to achieve far more if various contingent rules discriminating against them unraveled, so that women’s rights to engage fully and equally were protected. And, Tyler concludes, Hayek has turned out to be very wrong, while Mill has turned out to be absolutely right, on this particular point.

But you can also think about this in a non-Hayekian framework, that of simple game theory. More pertinently – and this is the argument of a great short piece by Jack Knight (slightly imperfect scan here – I’ll try to get a better one when I next get close to a proper scanner), you can think of it within a mixed motive coordination framework. The Battle of the Sexes game can, despite its crude and stereotypical framing, be used to shed light on the battle of the sexes.

Jack’s piece is less well known than it should be, because it appears as a chapter in an edited volume. It summarizes and clarifies the argument that he makes in his much better known book, Institutions and Social Conflict in some very nice ways. What it suggests is that Tyler’s criticism of Hayek can be generalized. Spontaneous order arguments (which rely on evolution), and arguments more generally that private actions lead to superior outcomes, are special cases of a more general framework. They are likely to work best when people are indifferent between the possible outcomes, or where power disparities between people are negligible.

To understand this, let’s start with the mixed motive coordination game itself. The miracle of Google Image Search reveals a version of the Battle of the Sexes game on an economics education website, in all its unreconstructed and awful glory, in which “MAN” dukes it out with “WOMAN” over whether or not they should should both go to the “Boxing” game, or just go “Shopping” instead.

![]()

Happily, you can substitute out the crude gender assumptions without changing the math. Let’s assume instead that two individuals, with non gender specific names, Pat and Lindsay, are in a relationship. They disagree over how they should spend a night out, even if they both love each other and agree that they want to spend it together. For boxing and shopping we can substitute in – I don’t know – Dungeons and Dragons versus going to an arthouse movie – or whatever other pair of alternative activities you like.

The payoffs in this game reflect the facts that (a) both actors are better off coordinating, and (b) that they have different preferences over how they coordinate (that is why it is mixed motive coordination). Both Pat and Lindsay have higher payoffs when they coordinate on the same strategies than when they don’t. Indeed, if they fail to coordinate, each of them gets the “breakdown values” with zero payoffs. However, they disagree over what they should coordinate on. Perhaps Pat prefers Dungeons and Dragons (they get a payoff of 2, and Lindsay gets a payoff of 1), while Lindsay prefers the arthouse movie. In short, they have shared incentives to coordinate, but clashing incentives over which strategies they should coordinate on

What Jack does, in the chapter that I’ve linked to, is to suggest that this simple game tells us a lot about where informal institutions come from, and how they work. There are a lot of informal institutions in human societies – informal rules that aren’t laid down by the government, but that are pretty pervasive. Think about how people queue in different countries. Think also – to make the stakes clearer – about the informal but harshly enforced expectations that Black people would make way for White people if they encountered each other on the sidewalk in the pre-Civil Rights South.

Jack suggests that these informal rules and social institutions are the culmination of a myriad of mixed motivation interactions. To illustrate this, we can apply the battle of the sexes framework to the actual battle of the sexes that Tyler highlights. We can stick with the players who are identified as MAN (here, some representative man in a given society) and WOMAN (here, some representative woman), but with quite different valences. Instead of reproducing cliches (those women, they love their shopping!), we can use this framework to ask about the deep processes that the cliches arise from. Where does the norm that women ought focus on household duties arise from? Why, more generally, do many norms emerge that restrict the activities of women, while providing an expansive role for men?

As Jack notes in his book, across a wide variety of societies, “informal rules have structured relationships between men and women in such ways as to produce long-term distributional differences.” In non-academic language, informal norms have emerged across many societies that disadvantage women in multiple ways (e.g. denying them full property ownership, or ability to participate in public life). And Jack’s argument is that these rules have emerged from many, many interactions between men and women, in which men systematically had the upper hand. The battle of the sexes is played again, and again, and again, between different men and different women. And as it is played repeatedly, shared expectations emerge, which then become informal rules, that everyone ‘knows,’ even if they do not necessarily like them.

The key to this argument is the breakdown values – the payoffs that actors get if they don’t coordinate in a mixed motive interaction. In the simple game above, these payoffs are symmetrical: everyone gets zero payoff if they fail to coordinate. But what if the payoffs are asymmetrical? In other words, what if one actor ends up only mildly worse off if there isn’t coordination, while the other ends off much worse off? In the actual battle of the sexes in most societies, women plausibly faced much worse outcomes than men, when they disagreed over something important. In the best case, women probably had much fewer or much worse outside options. In the worst case, they faced the threat of violence or death if they persisted in doing things that men would prefer they didn’t do.

The argument, then, is that these differences in breakdown options make it much harder for women to bargain hard for what they want, and correspondingly much easier for men. Both sides know that the woman will be much worse off than the man if they fail to reach agreement. And that in turn means that they are much more likely to coordinate on the strategies that favor the man.

As men and women engage in this kind of interaction, again, and again and again, they set general expectations which in turn lead to informal rules. Women figure out, as a class, that they are likely to end up worse off if they disagree with men, and men are able to make them back down. Norms emerge in a decentralized way that systematically favor the more powerful actor, and disfavor the less powerful one.

As a result, the rules that emerge from spontaneous orders are likely to reflect the power asymmetries within them. Such asymmetric rules are adhered to not because they are legitimate in any meaningful way, or necessarily deeply internalized, but because the disfavored individuals expect that they will be worse off if they don’t abide by them.

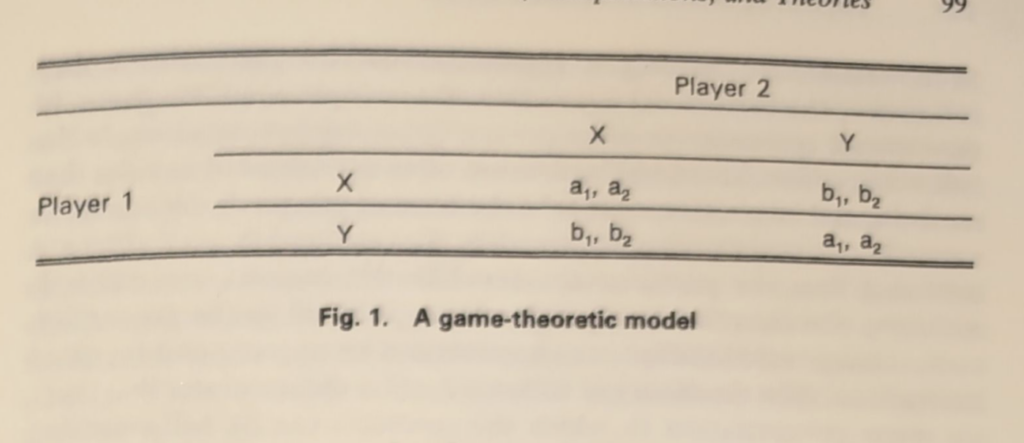

And this can be generalized. The kinds of evolutionary arguments that Hayek makes (e.g. that in a spontaneous order, rules will evolve that are to our broad advantage), and the transaction cost arguments made by institutional economists such as Williamson and North turn out to be special cases of the mixed-motivation framework. This can be seen if you look at a more generalized version of the 2×2 framework, where two players, Player 1 and Player 2 each have two strategies, X and Y.

If a1 is higher than b1, and a2 is higher than b2, then this is some kind of coordination game. Both players are better off converging on an outcome where they match strategies, playing X, X, or Y, Y, and getting the higher payoffs. If they play X,Y or Y, X they both end up with worse payoffs.

Jack argues that evolutionary accounts like Hayek’s will work best when a1 is equal to a2. That is, they are really arguments about pure coordination rather than mixed motive coordination. If neither Player 1 nor Player 2 really cares about which outcome they coordinate on – all that matters is that they agree – then the evolution of norms will be a relatively uncomplicated process. Whether it ends up at X,X or Y,Y will be arbitrary and possibly stochastic, since no-one is going to have any particular incentive to struggle or to disagree. The classic example of a pure coordination game is that of deciding which side of the road people should drive on – no-one cares much whether the rule says that it is on the left side or the right side, so long as there is a rule, and everyone knows it.

He argues that transaction costs accounts, like Williamson’s or North’s (some of the time: Doug was a colleague and occasional collaborator of Jack’s and sometimes shifted position) are often most plausible when b1=b2. These accounts predict that economic institutions will tend to be efficient – they will minimize transaction costs. Jack suggests that such institutions will only emerge in the absence of power asymmetries – that is, when the breakdown values of both actors are much the same. Under those circumstances, it will be impossible for one actor to use credible threats to force another to accept an outcome that it doesn’t prefer. Without power asymmetries, inefficient institutions, which benefit the more powerful actor at the cost of lower overall gains, are unlikely to emerge or persist.

For just the same reason, when there are significant power asymmetries, we are likely to see the opposite outcome – persistent inefficient institutions that benefit the powerful at the expense of overall wellbeing and efficiency. Indeed, Jack’s framework suggests that both evolutionary accounts and transaction cost accounts of institutional emergence and change are no more than special cases of a broader approach that does not assume either as a general matter that actors are indifferent between outcomes, or that actors have relatively equal bargaining power. Much, and likely most of the time, actors will have different interests (they will prefer to coordinate on different outcomes), or different levels of bargaining power (some will be much worse in the case of breakdown than others), or both.

In other words, power matters a whole lot. I suspect Tyler won’t agree with this claim – but Jack’s framework suggests that Hayek’s blind spot about women isn’t a special casem and instead a more general blind spot. Spontaneous orders and decentralized bargaining are only likely to lead to attractive informal rules under highly specific circumstances. And creating those specific circumstances will likely require a lot more social engineering than Hayek would be comfortable with. The JS Mill claim about women can be made pari passu about a whole variety of other groups who find themselves informally discriminated against across a wide variety of circumstances (and women still have to deal with powerful structural forces of discrimination, even if their prospects are now much better).

Two final points. One is that this argument (made in various forms in the late 1980s and early 1990s) speaks to a much more recent emerging literature that asks about the relationship between power and emergent informal norms. This paper by Suresh Naidu, Sung-Ha Hwang and Sam Bowles is one example. Liam Kofi Bright, Nathan Gabriel and Cailin O’Connor’s recent piece on the stability of racial capitalism is another. And one day, for that matter Cosma and I might harpoon our own Great White Whale paper and bring the proceeds into port (we do have a different piece on a very different topic coming out soon).

The other is that there are other aspects of Hayek’s arguments about spontaneous orders that only partly fit with this account. He suggests that they don’t just lead to better rules but better discovery. There is more to be said about this (and in particular the aristocratic elements), but that would require a post of its own.

{ 48 comments }

J, not that one 02.12.24 at 2:48 pm

I’m probably about the same age as you, just old enough to have run into the phrase “battle of the sexes” in my reading, from books not too long before I was born, or even contemporary with my reading. Though the term appears symmetrical, it was always clear that it referred to a recent conflict where the aggressor was feminism. That is, there was an accepted equilibrium that women disrupted. Books on feminism were accused of engaging in “the battle of the sexes,” and books against feminism were said to respond to that “battle.”

That kind of zero-sum thinking has itself apparently gone out of fashion, to the point where a lot of people seem to be surprised that even in dating there might be conflicts that line up on a gender basis. That is, in the terms proposed by the OP, Hayek would appear to have won the field without a fight.

steven t johnson 02.12.24 at 3:31 pm

Moving past the surprise that people still take von Hayek seriously, it’s difficult to see how an abstract study of emerging informal social norms clarifies when it neglects the pre-existing informal social norms. Perhaps if this was re-labeled “How Power Asymmetry Generates Informal Social Norms” if might be helpful? Except there is no definition of power given. (My personal thought is that power is command over sanctions, that is, rewards and punishments, due to position in the social structure, which may even allow a measure of power.)

Aside from the problems in seeing power asymmetry as something ascribed by the powerless, such as devolving into purely psychological projection, it’s not clear how power asymmetry isn’t an informal social norm in itself and all the various games just the expression of same, rather than inevitable outcomes of repeated processes creating structural causes.

In the case of Mill, the notion that physical strength is power forgets that even the strong men must sleep. And eat, they say poison is the woman’s weapon, no? The position of men has rarely centered on their personal prowess in hand to hand combat/heavy lifting. The ruling class is not comprised of prize fighters and stevedores. Even more to the point, it is entirely unclear if the battle of the sexes is, men vs. women, or husbands vs. wives.

In terms of game theory, perhaps the first game to analyze in the battle of the sexes is, having a baby? I think that’s a mixed motive game, individually played only a few times, but society wide it is played relentlessly, everywhere, constantly.

NickS 02.12.24 at 4:52 pm

That is a very helpful post; thank you.

Aardvark Cheeselog 02.12.24 at 5:16 pm

@1:

I am old enough to remember the televised Battle of the Sexes, and the notion of a “battle of the sexes” was in fact common cultural currency at that time.

As for OP, I am pleased to give precedence to game theory (actual math!) over the motivated reasoning of a guy whose whole career was pioneering achievements in wingnut welfare. I like that OP nails the kernel of truth at the core of the conservative bullshit argument as a special case (and of course an ideal one that does not occur in real social interactions).

Is the iterative game argument being made, that the starting power inequality between MAN and WOMAN is that MAN can beat the shit out of WOMAN if he gets annoyed enough? Everything can proceed from that?

John Q 02.12.24 at 7:12 pm

The symmetrical version of this game goes back to Schelling. Simon Grant and I had a look at various aspects here

https://www.dropbox.com/scl/fi/m3tg3h5kuayrtqtzurib9/Grant-S.-and-Quiggin-J.-1998-The-meeting-place-problem-Salience-and-search-Journal-of-Economic-Be.pdf?rlkey=4piaivrffvfs5pyn1v52fj0iz&dl=0

Ebenezer Scrooge 02.12.24 at 8:13 pm

I see the argument that spontaneous ordering will not lead to optimal results because power. This is a convincing argument that spontaneous ordering is imperfect. I buy it.

But it is not an argument against relying on spontaneous ordering. Such an argument would have to demonstrate a superior alternative. And this, of course, is a matter of context. Which leads us back to messy mushy somewhat interventionist liberalism. Which is prolly where we started from.

Brad DeLong 02.12.24 at 9:09 pm

#actually, Henry, boxing is not a “game” but a “match”…

Gar Lipow 02.12.24 at 9:42 pm

Jonathan Nitzan and Shimson Bichler did extensive work on power in economics, based primarily on econometric data analysis rather than game theory. Have not looked carefully at it. so can’t say how good it is, though from superficial read of it, seems to be solid. https://www.amazon.com/Capital-Power-Creorder-Political-Economy/dp/0415496802

Gar Lipow 02.12.24 at 9:47 pm

An afterthought: the writing style of the Nitzan work I recced in the other commentis offputting. I do think it is probably worth reading past that. I think the data and analysis are probably solid.

Tm 02.13.24 at 10:27 am

“Both sides know that the woman will be much worse off than the man if they fail to reach agreement. And that in turn means that they are much more likely to coordinate on the strategies that favor the man.”

This seems plausible and even obvious (although isn’t that more coercion than “coordination”?)

But: As men and women engage in this kind of interaction, again, and again and again, they set general expectations which in turn lead to informal rules. “

It seems to me that the informal rule – “woman will be much worse off than the man if they fail to reach agreement” – is already presupposed. This framework doesn’t explain the “emergence” of the rule. Honestly, I don’t see any original insight coming from this game.

Rob Chametzky 02.13.24 at 5:04 pm

Tim @ 10 “It seems to me that the informal rule – “woman will be much worse off than the man if they fail to reach agreement” – is already presupposed. ”

But that’s not an informal RULE at all, is it? Here’s the larger quotation that Tim @10 gives and from which it is taken

Both sides know that the woman will be much worse off than the man if they fail to reach agreement. And that in turn means that they are much more likely to coordinate on the strategies that favor the man.”

Rather, as the quotation says, it’s a piece of shared knowledge–a(n epistemic) state, not a rule. The second sentence in the quotation seems like a(n informal) rule, but it isn’t either: it’s a prediction/description of a one-off decision that is made in a specific situation.

And then this, the other quotation given by Tim @ 10

As men and women engage in this kind of interaction, again, and again and again, they set general expectations which in turn lead to informal rules. “

So, then, the explanation of “the ’emergence’ of the rule” depends on the situationally specific one-off decsion NOT being just a one-off at all, but rather (recognized and/or experienced as) being a token of type, so to say, and thus generalizable for guiding action (the emergence of a(n) informal rule). I hope this clarfies. One might still not “see any original insight coming from this game”, but it would be for other reasons.

–Rob Chametzky

J, not that one 02.13.24 at 7:15 pm

Unlike Aardvark Cheeselog (and like Tm, who is or isn’t the same person as TM?), I’m not sure the mathematical analysis is an improvement over more qualitative descriptions. I deleted a draft of a comment that I decided amounted to saying that the Victorians and Edwardians just knew a lot more about society and human nature than we seem to. We’re really not able to do the thing Cowen says Mill does where he unpacks social rules and understandings. We fall back on caricatures from Borscht Belt comedians and television cartoons from our parents and grandparents’ days. We’re much, much better at unpacking arguments on either side between whether society is essentially static or whether it’s always changing, but without much content.

J-D 02.13.24 at 11:21 pm

In game theory, ‘coordination game’ is a technical term for a family of ‘games’ (in the technical sense of game theory) where a player will get a better outcome (better for that player, from that player’s point of view) by selecting the same ‘strategy’ (also in the technical sense of game theory) as the other player does (that is, better than the outcome the player would get by choosing the other strategy).

Not all coordination games are the same game: some are absolutely symmetrical, but some are asymmetrical in ways which give one player an advantage over the other or (thinking about it another way) an opportunity to exploit the other player.

This technically narrow game-theory approach does not include within the model any communication between the players about choice of strategies. The question of coercion can arise when game theory is used to model some aspects of actual real situations, so what’s being assumed here is that a ‘coordination game’ model can still have some applicability in modelling some aspects of actual real situations even if coercion was another aspect of those situations.

Bill Benzon 02.14.24 at 1:12 am

Very interesting, Henry. Thanks.

TM 02.14.24 at 10:52 am

Rob 11: If the game is set up so that one side will usually win, do you really need game theory to arrive at the conclusion that one side usually wins? In the OP scenario, it’s baked into the rules, formalized as asymmetrical payoffs. So it is presupposed.

TM 02.14.24 at 1:52 pm

J-D 13: If you are presented with a choice to either agree with a demand or face adverse consequences (which is exactly the scenario presented in the OP), that to me is a form of coercion even if you couch it in game theory terminology.

notGoodenough 02.14.24 at 2:24 pm

TM @ 15

While I have no wish to speak for others and so would happy to be corrected on this point, my (admittedly superficial) reading of the OP is that it is more about the development and perpetuation of the social norms as a result of the power imbalance and their subsequent systemic distortions. Or, to put it very reductively, if the game is set up so that one side will usually win, both sides can come to that conclusion through playing the game and start playing in a manner which anticipates such an eventuality. Subsequently, you may end up with a game that has informal rules developing on this basis, which might not only increase the likelihood of that one side continuing to win but also perpetuate such occurrences even should the original power imbalance be somewhat redressed (“because of the implication”…).

Of course, that is merely my interpretation of the post (absent any judgement on its plausibility, applicability, and/or novelty), and my understanding may well be incorrect – I merely proffer this perspective in the hope it might be a useful for your consideration.

jp 02.14.24 at 9:42 pm

A possible implication of this: technological change which reduces the economic value of physical strength is liberatory for women. If the historical source of men’s social power was that their average higher physical strength creating resulted in greater economic power, automatization (reducing the value of physical strength) and the concomittant rise of the knowledge economy, would diminish this power imbalance, allowing women to reassert better norms and win increasing number of ‘games.’

J-D 02.14.24 at 10:16 pm

Thank you for the explanation, but I’m not clear on what impelled you to provide it. I was already aware of the meaning of the word ‘coercion’. Is there something about my presentation that gives the impression of a person who struggles with their vocabulary?

Wonks Anonymous 02.15.24 at 12:48 am

Re #2 steven t johnson:

There is indeed more than physical strength at play. Just as male humans evolved to have more upper-body strength than females, they also evolved to be FAR more homicidal. Women may be capable of poisoning their husbands, but they don’t actually do so that often. If we look at ancient DNA, it appears there were male lineages that spread out, killed the males already there, and had children with the local women. There is no female equivalent of Genghis Khan, so they’re less apt to figure murder is a good way to improve their lot. William Stuntz noted that in Gilded Age Chicago 80 of women tried for killing their husbands received no punishment. Regardless of the law of self defense as written, there was an implicit norm among juries that this was acceptable. If women were more homicidal, there would be less of an assumption that extraordinary circumstances must have necessitated such actions.

Henry Farrell 02.15.24 at 1:54 am

There goes my MAN card …

jack morava 02.15.24 at 2:06 am

This may be of interest. [It is not as technical as you might think.]

Notes on two elementary evolutionary games: https://arxiv.org/abs/1011.0069

abstract: In the first part of this note, we show (following Hofbauer and Sigmund) that Dawkins’ “Battle of the Sexes” defines an interesting map from a space of economic parameters to psychosocial coordinates. The second part discusses an even more elementary game, but one which is not completely trivial.

Alison Page 02.15.24 at 7:16 am

I know the OP and some commentators are more sophisticated than this, but I see across the thread an assumption that there is a cold equation – that women are by the nature of reality disadvantaged against men. But like so many supposed raw facts of nature, this arises from social conventions, which are perhaps so widespread that we may overlook that they are decisions we have made, continue each hour to make, and can unmake. And those decisions in turn give disproportionate power to men, who then have an understandable interest in presenting them as a natural background state to which humans must react.

For example, it is true that when I have a child it is harder to ‘go to work’ and earn money, just at a time when I need money the most. I therefore have a ‘negotiation’ with a man, and the rest (as described in this thread). But it is not a fact of nature that human society should allocate available resources only for one type of work, and other tasks are called ‘not working’.

It is a weakness of capitalism that it has no straightforward route for allocating resources to creating and socialising human beings, although it needs that task to be done. That is a weakness of the system we are embedded in, not of the people – largely women – who operate in the gaps in the world machine, propping it up hourly, at disadvantage to themselves.

TM 02.15.24 at 8:07 am

J-D 19: same here, I have no idea why you felt the need to provide the explanation at 13.

notgoodenough 17: The reasoning is entirely circular. The game model explains exactly nothing. I didn’t think I’d have to point this out.

J-D 02.15.24 at 11:59 am

That variation in upper body strength is under genetic influence is hard to doubt. That variation in propensity to commit homicide is under genetic influence is easy to doubt.

notGoodenough 02.15.24 at 12:35 pm

Alison Page @ 23

“but I see across the thread an assumption that there is a cold equation – that women are by the nature of reality disadvantaged against men”

I certainly wouldn’t presume to speak on behalf of anyone else, but personally I would not make that assumption (and if I have given that impression, I can only apologise for my lack of clarity).

It seems to me (and please do correct me if I have missed your point) that you are noting that social norms are not intrinsic but rather social constructs – for example, that the exploitation of social reproduction reflects a systemic issue (rather than being something inherent)?

If so, I think we would be broadly in agreement. For me, the discussion has been about how/if power imbalances can entrench themselves informally through the development of social norms predicated based on anticipation of that power imbalance – but that doesn’t require an assumption regarding how such power imbalances arise in the first place. Or, to put it simplistically (but hopefully humorously!), the suggestion that a society in which kings have power over peasants may develop social norms reflecting that does not require belief in the divine right of kings!

It is a weakness of capitalism that it has no straightforward route for allocating resources to creating and socialising human beings, although it needs that task to be done.

I suspect that, from a capitalist perspective, that is (as they say) a feature not a bug…

(I was tempted to make a long comment on how I think capital benefits from reinforcing class interests via historical subordination – both to its material benefit and as a form of undermining class solidarity – as an illustration of how social norms might develop from power imbalance as well as how capital resolves tensions between labour extraction and the necessity of social reproductive labour, then expand on that into why I view class consciousness as a necessary component of the rejection of the power imbalance that leads to such exploitation which I see as artificial distortions. However, I’m sure much to everyone’s relief, I will refrain as [a] I doubt there is value to my layperson’s musings, [b] it would be long, rambling, and mostly off topic even by my loquacious standards, and [c] I have mostly stopped commenting on the internet due to what I perceive as diminishing returns. Nevertheless, I would probably gesture vaguely in the direction of much of socialist feminism to get a feel for where I am coming from with respect to this point.)

Finally, thank you for posting your perspective – I appreciated reading your thoughtful comment, and your highlighting (what I would see as) a rather important point.

Wonks Anonymous 02.15.24 at 12:57 pm

I see I left out a single character in my earlier post, giving the impression that it was 80 total defendants rather than 80%.

steven t johnson 02.15.24 at 2:55 pm

Wonks Anonymous@20 “Just as male humans evolved to have more upper-body strength than females, they also evolved to be FAR more homicidal. Women may be capable of poisoning their husbands, but they don’t actually do so that often. If we look at ancient DNA, it appears there were male lineages that spread out, killed the males already there, and had children with the local women. There is no female equivalent of Genghis Khan, so they’re less apt to figure murder is a good way to improve their lot.”

It is not clear to me that men are genetically determined to be more homicidal. I’m pretty sure women have found it just as easy as men to kill animals for food or to fight a predator when cornered. Being able to kill animals for self-defense or food means I think the emotional capacity to kill other people are always present, with natural individual variations. The multitudinous vicissitudes of life mean such occasions will inevitably arise. In principle both men and women should be able to kill, which seems to me to be confirmed by the experience of others, historically and currently.

Nor is it at all clear to me that evolution has somehow the power to target the capacity for aggression so narrowly that the capacity to kill animals is unrelated to the capacity to kill other people. Unlearned complex behaviors, aka instincts, are not typical of human beings. Learning is, which seems to me, the opposite of instinct, maybe even the defining difference of humans from other primates? I will point out that is killing others is part of the supposed evolutionary instincts that children should be killing each other at greater rates than they seem to be. It does happen, but the notion of evolution as perfecting traits is a religious hangover rather than good science, in my best judgment. The notion that technologically primitive forager bands of humans could afford to kill each other off like gangster movies or the Game of Thrones strikes me as somewhat deranged.

I do not know how to choose between claims women are less violent by genetic nature from the claim the smaller party in a conflict is less apt to begin physical violence because they are more worried about losing. Even more, I do not know how anyone can be so confident that all women who poison are getting caught. “Witch” is also another word for poisoner, a point which is not by the way. If women were indeed less apt to physical violence even against smaller and weaker opponents, that would explain why historically there has been little or no corporal punishment of children by mothers, much less gross physical abuse, though. And overlaying was always a male slander.

There is a hint of the old idea that men are genetically selected to beat up or kill other men in competition for women. But it seems to me this kind of sexual selection should have created a powerful tendency for larger males, as their harems would be so much larger and their genes would dominate the gene pool. (Thus the reference to Genghis Khan?) But, the classic examples of sexual dimorphism due to this are the silverback gorilla (males maybe twice the size of females) or the elephant seal (males ten times.) The modest sexual dimorphism between male and female humans (a mere ten percent at most?) seems to me to be as likely to be due to the role of testosterone in making more body mass, which would interfere with reproduction in females. The evolutionary advantage of size is not usually contested.

I must say my notion of evolutionary psychology is entirely unlike that of the Hanson/Mercier/Simler/Sperber ilk. For instance, my thought is that there is no genetic programming for offspring, that the genetic programming is the capacity for orgasm, which provides the primary individual motive. The evolutionary outcome, children, is the result. (And popularly publicized figures about anorgasmia should raise very pointed questions for the standard EP enthusiast.)

Insofar as techonologically primitive forager bands wanted children as laborers, fighters and old age insurance, my belief is that the physical necessities of finding food meant that cooperation with women and men in the band was absolutely indispensable. Patriarchy has never seemed to me to be a coherent concept, but if it is coherent it is an aspect of a class society. But it is prehistory when most of the alleged evolutionar programming of men took place?

By the way, I’ve never been quite sure how they knew the Genghis Khan gene was actually Genghis Khan’s, rather than that Merkit dude who kidnapped his wife Borte?

Last and least, I’m sorry but I slipped and used irony. I suppose you can congratulate yourself if you spot the sarcastic statements?

K.R. McKenzie 02.15.24 at 3:18 pm

I suppose what I don’t understand is that, to me, Hayek would agree with everything written in this post. To be more specific, you write,

<

blockquote cite=”Better rules will emerge through an unguided evolutionary process within a broader constitutional order, whose main function is to guard against forces that might disrupt this spontaneity.”>

Wouldn’t Hayek simply say–exactly what you point to here–the importance of the broader constitutional order, is the key to solving the power imbalances you highlight? That is one of the more important reasons for a constitution: to protect the rights of individuals, equalizing power imbalances between groups and factions. And therefore once these power imbalances are corrected by a constitutional order we get closer to that ideal setting in which spontaneous order can function well?

Of course we can see that the original U.S. constitution, or constitutional order, did not level the playing field well for women. It was amended to do so, and that is good. And so I think this goes back to the original deep question that Tyler (and Mill) were highlighting: how do we know when a constitutional order is working well or not? What information can or should we use to try to understand that?

notGoodenough 02.15.24 at 4:18 pm

TM @ 24

The argument you interpret the OP as making (e.g. “if the game is set up so one side will usually win, one side will usually win”) is indeed circular. My only intention was to make you aware that that is not the argument I interpreted the OP as making, and instead was under the impression a different argument was being made (e.g. “if the game is set up so one side usually wins, social norms will develop which informally reinforce and exacerbate that, and this can lead to that side continuing to win even if the rules have changed so that both players should theoretically be equal). Certainly someone might disagree that my interpretation is correct (or whether or not such an argument is reasonable), but I didn’t see the argument I thought was being made as being circular. However, since I have apparently trespassed upon your time for no reason, I apologise and retract all comments. Un salud!

Wonks Anonymous 02.16.24 at 6:00 am

steven t johnson @28:

You may be skeptical about genetics causing differences in inclinations to commit homicide rather than mere capacity, but there is no actual reason to think such inclinations are not heritable or not subject to selection. Males being more homicidal is a cultural universal among humans, and if we look at chimpanzees the same thing applies to them. You mention hunting, and women are indeed capable of that, but again it is a cultural universal that males hunt more than females.

https://twitter.com/Evolving_Moloch/status/1692536478210162909

Human sexual dimorphism is indeed modest compared to species where harems are the norm. But it’s quite different from zero! If no male could reproduce unless he had killed any rival males in the area, then we’d see more dimorphism and higher homicide rates. As it is, in contemporary society committing homicide is highly atypical. But among those who DO commit it, their sex is overwhelmingly male. And, no, it’s not credible that this discrepancy is caused by poisoners not getting caught.

You may think smaller scale societies could not “afford” to kill each other at high rates, but from what we can see they indeed did do so relative to their population size. In a state of anarchy with other tribes, pacifism is instead less affordable. As Steve Pinker has written, the world has gotten much less violent over time as professional police forces and militaries established firm monopolies on violence.

J-D 02.16.24 at 8:01 am

I can answer that. I thought there was a significant possibility that you didn’t understand what ‘coordination game’ meant in game theory. A person who is familiar with common use of the words ‘coordination’ and ‘game’ could easily be misled by that into a misunderstanding of the technical use of the expression ‘coordination game’ in game theory. You asked the question ‘isn’t that more coercion than “coordination”?’ which is just the kind of question that might be asked by somebody who had misunderstood the technical language in just this way.

If you were using the word ‘coercion’ in a technical sense which could easily be misunderstood by somebody familiar with ordinary uses, I could understand why you would have wanted to explain that, but the explanation you actually gave was just an explanation of the word’s ordinary use.

J-D 02.16.24 at 8:19 am

The suggestion that variation in propensity to commit homicide might be under genetic influence is the kind of thing that could easily be true but also easily be false. I don’t know whether it’s worth testing, but I’m sure that it would be difficult to test.

J-D 02.16.24 at 8:21 am

All the information available. What information did you use to reach the following conclusion of yours?

steven t johnson 02.16.24 at 7:11 pm

Strangely previous attempts at replies have disappeared before posting. Perhaps I’m not in best health and my typing skills are impaired. Hope this isn’t too curt, and comes off as personally rude.

Wonks Anonymous@31

There is only a rhetorical distinction between “mere capacity” and “inclination…” except that inclination implies mind-reading.

The insinuation that I’m claiming human behavior is somehow immune to selection is incorrect. I suggest that human behavior is not very heritable. And I suggest that the power of natural selection to perfect, or optimize such, is limited because, more of it is learned than “genetic,” the optimum is intrinsically fuzzy because of trade-offs between traits, random variation and genetic drift in populations, and perhaps most of all the optimum can change over time. (This last can act as stabilizing, random changes in the environment produce changes in the genotype but these can be reversed. The randomness can act to produce a kind of “drunkard’s walk” that ends up never very far from the lamp post.) I do not think natural selection is so powerful that it could program male children to not be violent until adulthood and thus the rather small number of child murderers is evidence against the genetic compulsion of male violence.

Further, the effectiveness of natural selection tends to be proportionate not just to the heritability (very doubtful for human behavior) but to its intensity. The high failure rates of matings and of actual conceptions powerfully suggests that the greatest selection pressure on humans is exerted before birth. Any sensible theory of evolutionary psychology would take this into account, one reason I don’t take EP very seriously.

Chimpanzees have 48 chromosomes. They are not human lineage. The arrangement of genes, the genome, matters in the expression of traits.

I don’t get anthropology from twitter/X.

Male violence is a cultural universal. So is female violence. And so is male pacifism and female pacifism. How much? is what matters. If the case for genetic determinism is to be made, there should be little variation in male homicidal tendencies across cultures and little variation in female pacifism. Male violence by this standard is not even a universal in the sense needed for the argument here. Additionally over time the variation of male violence and female pacifism (the same claim, after all,) even though culture changes much more rapidly than the gene pool for the descent group does, there is much, much variation in this supposed genetic trait. I think it parallels Lewontin’s demonstration of more variation within purported races than between purported races.

Male hunting is indeed commonly held to be a cultural universal. This is not even directly related to the issue of female capacity for violence/genetic pacifism. Women butchering animals are violent, ask any vegan. But I think women hunting is pretty universal, but it’s like a lot of things, they just don’t get the credit. “It’s just a rabbit.” I think it’s mainly because big game hunting which requires more travel to the farther territories where the big carcasses or hunks of meat require heavy lifting, which men really are good at.

The hypothetical about human sexual dimorphism if killing males really was prerequisite to reproduction is formally correct. The fact that human dimorphism is so limited is still evidence that violence against other males is not prerequisite for male reproduction. But it is still the case that sexual selection of the type posited tends to be a self-reinforcing, runaway cycle.

The arbitrary objection that of course women can’t be getting away with murder in any significant scale is not supported, despite the claim that men aren’t getting away with murder on any significant scale. I still say that historically attested fears of poison/witchcraft express repressed fears of (largely) female violence. The historical examples of women hunters and women warriors despite social roles, and the flip side, pacifist men forced into female dress and roles, make perfect sense as inevitable extremes in the spectrum of natural variations, ends of the distribution. But if men are genetically violent and women genetically pacifist, these instances are not variations, but counter-examples. Where do Night Witches or Bonnie of Bonnie and Clyde or that women with Starkweather or that woman sending out Aileen Wuornos come from. (That last one got away with murder, didn’t she?) Being a mutant is not the same as being closer to one end of a distribution! The notion that we have good figures on maternal infanticide is implausible in my judgment.

Pinker is not a reliable source. Percentages alone are an excellent way to lie with statistics. But maybe this does even Pinker an injustice? Pacifism in technologically primitive forager societies does not have to look like today’s pacifism, that’s silly. Pacifist bands move away surrendering rather than fighting! This is just wildly wrong.

I’m not sure whether econlib.org is regarded as sound economics, or just some libertarian talking points imposition on humanity? But the notion that economic decisions depended solely on total costs versus total benefits over a lifetime and children didn’t pay omits contributions during crises; network benefits from other people’s children as well; the difference in a marginal contribution by children in raising total output to a necessary level is not even conceived as important. (A hypothetical example of the last: The help from kids in gathering plants leaves an adult more time to accomplish tasks only they can do, like make a tent better or make arrows, even if in the long run they have to waste more food on them. These are not particularly far fetched scenarios.) But it is the claim that people have children for the same reasons as other animals that is staggeringly wrong. Not one person here had their mother go into heat and mate with all the males at hand. Animals have offspring because of instinct, genetic programming. People have sex because somebody wants an orgasm, which is the genetically programmed capacity (or inclination) to have sex.

As to the gerontocracies of Australia, I’m not the one promoting a monocausal theory or a metaphysical view of human nature. I’ve not idea. I’m not even sure what is to be explained, tens of thousands of years of “gerontocracy” or what’s happened in historical times. And I can’t assume anthropologists necessarily got it completely right either.

I did not know that Jochi, the presumed son of Genghis and Borte, did not have multiple wives and many children who could have spread the notorious genes in such a large proportion of the Asian male population. Or whatever explanation for saying it was the man himself, rather than some other relative who passed it on.

Glau Hansen 02.16.24 at 8:15 pm

@25, @28

“That variation in propensity to commit homicide is under genetic influence is easy to doubt.”

The variance isn’t genetic, it’s hormonal. Which indicates why it is strongly associated both with men and with adolescence, rather than with women and children.

Testosterone is a hell of a drug. And granted I’m speaking mostly from anecdotal experience (mine and a few friends that I have discussed this deeply with) but more testosterone makes you care a lot more about hierarchy, and winning, and makes physical responses to irritations more satisfying. It also makes it a lot harder to pick up on the emotional state of others around you- more just not noticing it, rather than not empathizing with it.

As far as physical strength goes- I don’t think it’s use in economic production matters very much. Nor is there a huge difference in capacity to kill between a strong person and a weak person. But there is a huge difference in the ability to win a fight. So at the moment when a decision is needed, passions are highest and interests differ, the threat of violence is most immediately useful to the strongest, because immediate violence rather than the future promise suffers the least from credibility problems.

Tm 02.16.24 at 10:56 pm

30: „if the game is set up so one side usually wins, social norms will develop which informally reinforce and exacerbate that, and this can lead to that side continuing to win even if the rules have changed so that both players should theoretically be equal“

This raises the question what the status of the „rules of the game“ is supposed to be if they don’t rely on social norms. The rules of the game being that men can use coercive force against women without facing adverse consequences. In my understanding, that implies the existence of social norms that this sort of behavior is at least tolerated. So the argument is circular: patriarchal social norms have already to be present for the game to work. Maybe the OP wants to clarify that point if he disagrees with my interpretation.

Wonks Anonymous 02.17.24 at 3:21 am

As it happens, scientists have looked into the genetics of extreme violence (including homicide):

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4776744/

J-D 02.17.24 at 8:50 am

That’s a false contrast, or at any rate a partly false contrast. It’s practically certain that variations in hormone production are under genetic influence. In particular, if it’s true that testosterone makes people more violent, it’s practically certain that on average men will be more violent than women because of differences in their production of testosterone, but men and women differ in their production of testosterone for genetic reasons.

Interesting. I don’t notice anything there, though, about differences between men and women.

steven t johnson 02.17.24 at 4:14 pm

My previous drafts touched on the “warrior gene” as well as testosterone.

Robert Sapolsky’s popular book Behave discusses the effects of testosterone. Despite Sapolsky’s love for EP, when speaking on contemporary neurophysiology, his discussion is quite nuanced.

Re MAOA-2R, see https://scientiasalon.wordpress.com/2014/07/31/the-extreme-warrior-gene-a-reality-check/ by Alondra Oubre. Oubre deemed the study of such claims worthwhile but emphasized the need for caution. As to the issue of violent men vs. pacifist women, it is notable that these studies in behavioral genetics treated these as genetic defects, not as adaptive features selected for in the species! And of course they made no comment on supposed reproductive advantage from these genes. This is not uncommon for EP in popular work, but it is hard to understand how you can claim to be talking Darwinian when you don’t demonstrate differential reproduction. But Wonks Anonymous fundamental claims are about the positive selection for male violence and female pacifism and how they leads to cultural universals. (The implied argument that cultural universals are necessarily genetic smacks of the circular, but there you are.) The question of whether alleged cultural universals are truly universal enough is more or less ignored. A true cultural universal in behavior, such as the need to sleep or rooting, in my reading tends to be ignored in the way a goldfish ignores water.

The statistics of GWAS, genome wide association studies, are very tricky to interpret. These are the kinds of studies that seem to be usually summarized as saying, trait A is X% hereditary. They generally do not pronounce on which gene does what. It is not at all clear to me what it means to say the entire genome is responsible for a trait. I think it can be misleading to speak of a gene for this or that. Indeed what a gene is, is more complex a question than you might think. The correct definition depends upon what you are investigating.

But the important point in the context of claims of innate behavior positively selected by nature (sometimes made in ways that seem to replace a Providential God making a perfect creation with Evolution( is—-there isn’t that much variation in humans by comparison to other species. If genes are so important that means something. And one thing it means is that the power of natural selection is blunted precisely because there’s not so much difference for the grindstone of natural selection to select from.

(By the way, EP’s doyens, at least Tooby and Cosmides, claimed behavioral genetics and EP were somehow entirely different, a position I think is something like claiming that looking at the recto side of a coin is entirely different from looking at the verso side. There are deep conceptual problems in the whole field in my best judgment.)

notGoodenough 02.17.24 at 5:23 pm

Tm @ 37

Firstly, thank you for the thoughtful response to clarify your position (given that much internet discourse seems to rapidly descend into pointscoring and ungenerous assertions, I genuinely appreciate your taking the time to lay out your reasoning in such a clear and fairminded fashion!). I certainly take your point, and think it entirely a reasonable critique (I’m not sure I’d say circular so much as incomplete – but honestly that would be quibbling rather than addressing the issue). It seems reasonable to note that the argument (as I understand it) does not address how the rules came to be, but only how things might change after the fact. I am not sure how one might go about meaningfully dealing with that point – it seems to me tied up in when you might call something patriarchal (I believe using forceful coercion occurs in many species, but I would hesitate to suggest it should be considered patriarchal – similarly, how one might apply this to humans or pre homo sapiens is something I wouldn’t dare to consider). Regardless, it is an interesting point, and let’s hope for clarification!

J, not that one 02.17.24 at 7:02 pm

The game theory analysis makes for a very enlightening example, however it clearly doesn’t even rise to the level of a thought experiment. What real world situation could possibly embody that matrix? Do little boys regularly beat up little girls on the playground? Do high school teachers regularly incorporate feats of strength into the curriculum? What person’s life and what relationships consist primarily of conflicts that are decided by physical force until one side gives up trying?

It seems in part these things operate by the principle that any model is as good as any other as long as someone has the will to pretend it can be carried through consistently.

If we removed the labels, and simply said that bullies always win and society agrees that bullies should win, we would be less quick to agree that this is just the way things have always been.

Wonks Anonymous 02.17.24 at 11:46 pm

J-D:

The study has a table breaking out males and females. There were 339 males in the violent offender group vs 21 females. For extremely violent offenders, there were 56 males & 2 females. Everyone already knows that males have a Y chromosome while females have two X chromosomes. I guess one could focus on the SRY (sex-determining region) on the Y chromosome as a specific gene distinguishing the two. But I provided the link merely to show that people have looked into genetic influence on violent behavior.

steven t johnson:

Recall when I cited Pinker on violence declining in the face of professional police & militaries? Long ago those did’t exist and violence was valorized rather than regarded as a “defect”.

Napoleon Chagnon measured an association between homicide & reproductive success among males in a pre-modern society.

I didn’t bring up Chagnon’s findings in an earlier comment because it was merely a comment intended to have limited length.

The idea is that culture varies a LOT, so if you find something is the same everywhere that indicates some kind of constraint.

How has it been “ignored”? I brought up that it is indeed a cultural universal, as anyone who has studied the subject knows. You have not actually made any argument against its universality. Give me an example of a human culture where females commit homicide at rates comparable to males.

We find that in other species of animals that we wouldn’t even regard as having a culture. It is invariant within any population. Why prefix that with “cultural”?

I just linked to a study in “which gene” was specified, and they discussed the outcome associated with it. True, we don’t know the metabolic pathway, but neither did Mendel when he discovered genetics.

Who is claiming “the entire genome is responsible”? Your entire genome may have resulted in you, but much of it is non-coding neutral genes that would not have any detectable effect, and other functional genes will affect some traits but not others.

There are differences in behavior like homicide, and there’s an obvious reason studied in evolutionary game theory. In addition to “battle of the sexes” there is also “hawks vs doves”. Hawks do well against doves, but badly against each other. For doves, it’s the reverse. The result is an equilibrium without either trait being “fixed”.

Darwin didn’t know about genetics when he came up with selection theory. So we have proof one can effectively engage in such reasoning without genetics, but E. O. Wilson was right about consilience, so the ideal understanding would integrate genetics as well.

Wonks Anonymous 02.17.24 at 11:50 pm

As I said above, all human females have two X chromosomes, so we’re not specifying a gene on the Y responsible (unless it’s the SRY). However, there is variation among them in how much exposure they have in the womb to androgens:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4350266/

Among the effects found was “increased tendencies to engage in physically aggressive behavior”.

J-D 02.18.24 at 4:57 am

Yes, I noticed that and I appreciated that. Thank you for that.

I don’t think it’s in dispute that men commit more violence than women. To what extent (if any) there are genetic reasons for that is a more difficult question, and I don’t think the particular study you cited shed any light on that.

If, as another commenter has suggested, testosterone makes people more violent, that would provide a link between a genetic difference between men and women and a variation in propensity for violence, as I acknowledged.

steven t johnson 02.18.24 at 3:30 pm

Wonks Anonymous@44 “Who is claiming ‘the entire genome is responsible’?” I’m tempted to say, every GWAS, but that’s not literally true. But every GWAS is fuzzy on this issue due to the nature of such a statistical study. It’s in the very name: Genome Wide Association Study. Strictly speaking, there is a difference between no effect and no measurable effect. In one sense GWAS estimates effects of total genome because the effects of proposed genes can’t be detected. This kind of statistics is easy to misinterpret. Correct math doesn’t necessarily guarantee the right answer, sorry. Both fallacies of composition and ecological fallacies seem to me snares for the unwary.

Again, the very notion of a functional gene depends very much on the investigative process. It is altogether too easy to speak of genes for a trait, implying a straightforward process of natural selection. Larry Moran’s Sandwalk blog over the years had some very enlightening discussions on this. Finally, your life resulted in you and the genome was “merely” part of it.

“The idea is that culture varies a LOT, so if you find something is the same everywhere that indicates some kind of constraint.” But “it” is not the same everywhere! My experience has been that some alleged universal is not when you actually look at the concrete details. People claim “religion” is a universal, which only proves they have a very abstract and limited notion of religions, uncontaminated by any in depth knowledge. The need to “find” universal male violence vs. female pacifism is leading to false pictures, where different forms of female violence are omitted as not fitting the template. And variations in male violence are ignored, especially evidence of male pacifism, despite being evidence that genetic factors are not the real story.

Pinker’s “theory” that male violence is genetic contradicts the decline in violence he wants to claim in a different book (Blank Slate vs. Better Angels.) Insofar as there is a possible genetic factor, it is because male pacifism is also a hereditary capacity! Or inclination, if you insist. The problem for Pinker’s crusade against the Standard Social Science Model is that it is the Gold Standard of evidence, to be explained. Genetics as an explanation for cultural diversity is obviously a fool’s game. But genetics as causes of imaginary universals is pseudoscience, in my best judgment.

“Give me an example of a human culture where females commit homicide at rates comparable to males.” Misled by bad biology in defense of worse social science, you don’t even know how to ask the right questions. I think real female homicide rates are sharply underestimated, and male pacifism is not even examined. Nor do I think that the homicide rates have to be equal to be comparable. You are not doing science if you don’t think of testing alternatives. If violence is indeed male, then smaller men will commit homicide on larger men at rates comparable to the reverse. The answer to that question will show us how we should discount the role of women’s generally smaller size plays. In a sense of course that is a genetic factor, but it is entirely not what Pinker and you are talking about. (For what it’s worth, my personal experience is that unusually large women or for that matter older sisters, most certainly do initiate physical violence more often than smaller ones. But of course nothing can be as convincing yet misleading as personal experience.)

“Why prefix [sleep] with ‘cultural’?” This is an excellent example of how EP finds fake universals. Sleep is also cultural. Sleep during the day or the opposite, wakeful periods in the night, vary from culture to culture. The experience of sleep includes dreaming, which is wildly variable. Of course, sleep is a true cultural universal. But the cultural differences are minor. And the hereditary similarities are usually vastly more important, so that forgetting the cultural variations in sleep rarely misleads anyone into error. A true cultural universal such as EP claims to find here, there and everywhere (the notorious list by Donald Brown is very commonly cited, despite its foolishness!) should be much the same. The amount of variation between cultures should be much less than the similarity.

Napoleon Chagnon? Consult Marvin Harris for one before assuming Chagnon is definitive, as opposed to well-known.

E.O. Wilson and consilience? The basic metaphysical propositions of materialism have been confirmed by centuries and centuries of experience, and I personally am confident that any overtly anti-materialist or covertly dualist unspoken premises can be correctly judged as, Not Even Wrong, not science at all. But that’s me. But no, there is no consilience in practice, not even in fundamental physics where QM and GR are incompatible. Kuhn’s notions of paradigmatic revolutions in science I think suffers from forgetting that there is so often a counterrevolution attempted. Old ideas in new jargon can mimic the style of science but still be motivated reasoning.

TM 02.19.24 at 12:23 pm

notgoodenough: Thanks for your polite reply.

“It seems reasonable to note that the argument (as I understand it) does not address how the rules came to be, but only how things might change after the fact.”

I would go further and say that the game theoretical model sheds no light on the question “how things might change after the fact”. It only tells us that if the rules are so and so, the outcome of the game is likely to be so and so. If the model is supposed to shed light on real world social processes, the modeler needs to do a lot more work than simply to say “here’s my model isn’t that interesting”. Sorry but I have little tolerance for these games.

Henk E. Goemans 02.19.24 at 10:05 pm

This is really nice! I’ve assigned it to my class in the week on coordination.

Just one thing nags me: coordination of course also creates power.

Comments on this entry are closed.