This new Chronicle article by Michael Vasquez on a surreptitious effort by a non-profit organization to get conservatives elected to student government positions is worth reading throughout. There’s absolutely nothing wrong with conservatives organizing to get elected – what’s fishy is the stark contradiction between the organization’s private self-understanding (a “rather undercover, underground operation” to change politics on campus) and its public self description. See further this Amy Binder piece for a description of the background politics – what is happening, more or less, is that bomb-throwing conservative campus organizations are sparring with the more sedate and traditional ones for the money and attention of donors, and winning.

But what I wanted to single out was this bit, which very much reads to me as one of those ‘the journalist strongly believes that there is something interesting going on, but hasn’t nailed down interview or documentary evidence’ hanging observations that you sometimes see in news articles (I understand from talking to journalists that such paragraphs are often a way of shaking the tree – if you put something out there, it may encourage others to come forward with more evidence).

Yet there is one policy proposal that almost always shows up with Turning Point’s candidates: promoting Uber.

The ride-sharing service has long been touted by conservative politicians as an example of free-market innovation. Student government can push for Uber in two important ways: lobbying local municipalities to allow Uber service on campus, and setting aside student-government funds for late-night “safe ride” programs that provide free or discounted Uber service to students.

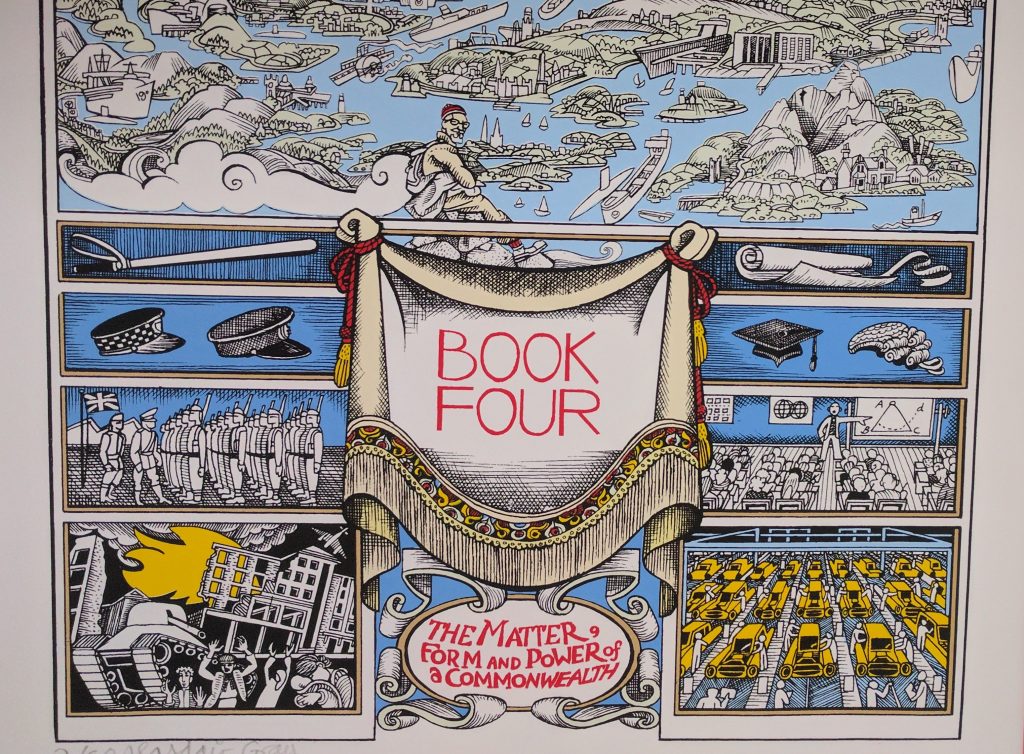

In Mr. Kirk’s book, a group of “Turning Point USA activists” are credited with helping the University of Southern California’s student government reach its free-ride arrangement with Uber. Mr. Kirk’s book mentions Uber 42 times.

… At the University of Alabama at Tuscaloosa last year, the student-government president at the time, Lillian Roth, was an outspoken supporter of bringing Uber back to campus. She even met with Tuscaloosa city officials on the issue, and the city allowed Uber to resume service last summer.

Ms. Roth was endorsed by Turning Point’s student chapter at Alabama. Her father, Toby Roth, has long been active in Alabama politics and is a registered lobbyist for Uber. Mr. Roth said his daughter didn’t have a conflict of interest in advocating for Uber.

“She was not a decision maker in the process,” he said. “Whether or not Uber came to campus was not in her discretion. If she was on the City Council in Tuscaloosa, if she was the mayor of Tuscaloosa, then yes, I think recusal would be in order.”

Notably, Vasquez shows that it isn’t just activists at the University of Alabama at Tuscaloosa that have been pushing the pro-Uber perspective. Perhaps the elective affinity between conservative campus activism and promoting Uber is just so compelling that pretty well everyone whom Turning Support has helped fund independently sees this as a core issue. Perhaps not.