I was recently part of an online discussion that asked this question. People were talking about industry, democracy, civil society, world leadership, you name it. But nobody was asking the obvious question: when, in fact, will the sun set on the United States?

Yes, I’m going there. [click to continue…]

{ 18 comments }

People are wondering how Trump could get away with nationalizing 10% of Intel, with plans to acquire more corporate assets for the Federal government, while hardly hearing a peep from other Republicans. Isn’t this socialism, which is anathema to the Republican Party? Uhh, no. It’s National Socialism. Contrary to some right-wingers, who try to blame the left for fascism because the Nazi party had “socialism” in its name, that interpretation of what fascism was about is like thinking that the fact that the official name of North Korea is “The Democratic People’s Republic of Korea” somehow discredits democracy.

{ 26 comments }

My friend was bitten by a dog this summer. For British readers: being bitten by a dog elsewhere in the world isn’t merely painful, scary and shocking. It brings with it a real possibility of rabies. For non-British reader – really, I’m not making this up, there’s no rabies in the UK. My friend is here in Madison, and it was a drive-by bite, so he never saw the dog’s immunization papers, and can’t get it put down. He’s had to go through the course of preventative rabies therapy, and is clearly experiencing a certain level of trauma, not really wanting to go out in his neighbourhood. I suspect that, like me, he’ll now have a lifelong fear of dogs. Which, of course, may serve him well.

My experience being bitten by a dog was far more satisfying. The Miner’s Strike was half way through, and friends had organized a benefit concert with The Pogues in Camden that I planned to attend. Beforehand I decided to go up the shops to get something for dinner. As I walked up the road I noticed a bloke in a torn dirty old man mac gesticulating wildly to me from a distant phone box. I slowly twigged he was not alone in the box – he was accompanied by a 5-year old girl I recognized from the a house a few doors away, and a good-looking rather well dressed chap around my age. He seemed completely nuts.

{ 19 comments }

I managed to time things perfectly – I had a conference in Manchester after day one of the Cheltenham festival, which our friend Bob hasn’t missed since 1953, so we all went to see the first day of Gloucestershire v Hampshire (starring Wisconsin’s own Ian Holland!) at Cheltenham, and I booked a rail ticket from there to Manchester Piccadilly (via Birmingham New Street, naturally) for late in the day. Dad always liked to leave a red ball match shortly after tea, so he and Bob left me to watch an additional hour of play before getting the train.

I wandered off with plenty of time to spare and, as I approached the station, had that sense of dread known to most who regularly use English railways. About 150 people milling around outside the station even as two busses, both clearly replacements, left the station forecourt, bade ill for my trip.

ON investigation, all services to New Street were cancelled indefinitely. We were told, definitively, that no more replacement busses could be found. God knows why I cared – to be honest I’d be as happy spending the night in Cheltenham as in Manchester – but there were a lot of disoriented and pissed off people milling around. I was chatting with a very distressed young woman (20ish) from Bath University who was hoping to reach Middlesborough (good luck) when, looking at the announcements board, an alternative occurred to me. And this is what I love about the English.

The young lad (I suppose he was in his mid-to-late 20s, but he looked 13 to me) who appeared to be in charge of the whole business was, let’s say, stoical, despite being besieged by hundreds of people many of whom were being quite rude to him, poor chap. I sidled up to him and said “So, there’s no trains to New Street this evening right? Probably a death on the line?”. He confirmed my worst fears. “But: trains are still running to Worcester Foregate?” – he assented. “And, presumably, we could all get the next train to Foregate street, change there, and get a train from there to Birmingham Moor Street, from where we could walk to New Street?” (It’s a very short walk). His eyes lit up: “Yes”, he said, “What a good idea! That would work brilliantly!”. Then his face fell, “But how would people know how to get from Moor Street to New Street?”. “Well”, I said, “The most absurd strategy would be to tell them to follow me since I know what I am doing. Or – they nearly all have phones, so could navigate themselves. Another option would be to send an employee to lead them across the city”. He chose the most absurd option.

And so it was that I led about 200 people onto the train to Worcester. Funnily enough, when we reached Worcester Shrub Hill the station staff seemed to know what was going on and told everybody to get off there rather than carry on to Foregate Street, presumably because it facilitated getting an earlier Birmingham train out.[1] By then I was kind of stuck with the 20 year old woman – she was using my portable battery to charge her phone (god she was anxious) and on the one hand I didn’t want to weird her out by talking to her much, on the other hand I didn’t want to lose my portable battery, which I was going to need. With us were a young man from Hull who I genuinely couldn’t understand, and had to pretend to be deaf every time he said anything to get him to repeat it, and a slightly more comprehensible young woman from Derby: I thought they were a couple – more on that in a minute. As we all approached Birmingham I worked out that Snow Hill is as close to New Street as Moor Street is, and I knew it was an easier station to exit; combined with the fact that we’d reach Snow Hill 3 minutes sooner than Moor Street I suggested to the whole train that we all exit there for the walk to New Street. Bold, because I’d never actually walked that particular route myself.

Everything worked out though, and I successfully led my couple of hundred passengers from Snow Hill to New Street, feeling triumphant.

Until we reached New Street.

{ 11 comments }

Over at Talking Points Memo, Josh Marshall has been making the case that the states are critical sites of resistance to Trump’s lawless power grabs on the road to authoritarianism. He was challenged today by a reader who asked him what, specifically, the Blue states can do. Marshall tossed out some ideas: Secure the vote, sure. But we should already expect this, and it’s still a very defensive move, not chipping away at Trump’s expanding power. Withholding taxes collected from state employees from the Federal Government. I am not keen on this, as it is probably illegal. And why wouldn’t Trump retaliate by stopping all Federal payments to California? Arresting masked and out-of-uniform ICE agents who refuse to identify themselves. Maybe, but this could get dangerous very fast.

Strategizing like this is not really my thing. But I have an idea. And I think it could be significant. Over at Vox, Dylan Matthews argues that Trump’s 15% tax on Nvidia’s and AMD’s chip exports to China is flagrantly unconstitutional. It’s not just that Trump lacks any authority from Congress to impose this tax. It’s that Article I, Section 9, Clause 5 of the U.S. Constitution says, “No Tax or Duty shall be laid on Articles exported from any State.” Trump is imposing a duty on a major export from the State of California. This looks like an open-and-shut case, easy to understand.

The difficulty is that Nvidia and AMD have caved on this, because Trump has so many other ways to get back at tech companies if he wants. He could, after all, simply prohibit chip exports to China, which would be perfectly legal. So this is extortion. Nvidia and AMD, although they have legal standing to object to Trump’s illegal tax, and would likely win their case if they filed one, would lose financially from Trump’s retaliation if they filed.

So here’s my idea: Governor Newsom and Attorney General Rob Bonta should sue the Trump administration to stop the 15% export tax on Nvidia’s and AMD’s chip exports to China. I know, I know, neither China nor the big tech companies are popular. But hear me out.

{ 13 comments }

There’s been a lack of cheer on this site lately. The obvious response: some analysis of trivial, ephemeral pop culture.

So, a question before the jump: If I were to mention “the MacBride and Kennedy stories”, who would raise a hand and say “I know!” ? — It’s okay to say “no idea”, btw. This is a fairly deep cut. But here’s a hint: it connects to a recently released summer blockbuster.

[click to continue…]

{ 6 comments }

Human beings are creatures who can describe their actions at various levels. Elizabeth Anscombe has famously introduced the example of a man who moves his arm, to pump water, to poison the inhabitants of a house, to overthrow a regime, to bring peace.* You can play with this case, or others, to create all kinds of variations: which of these descriptions does a person know of? Which elements could be outsourced to others, who might not know other descriptions? This is the stuff of comedies, tragedies, and detective stories. And arguably, it matters immensely when it comes to the introduction of AI and other digital technologies into our work.

I was reminded of this basic insight from the philosophy of action, about the multiple descriptions under which our actions can fall, when, the other day, I had to do the proofs for a paper. In the past, I had seen proofing as an act of care – a loving gaze that spots the last mistakes and makes the last improvements before a text goes out into the world. Not the most exciting part of academic work – the arguments have been made, after all – but a meaningful closure of the sometimes bumpy road to publication. I’m the generation who always got pdfs; generations before me did it on paper.

{ 10 comments }

A book review from Inside Story: After The Spike by Spears and Geruso

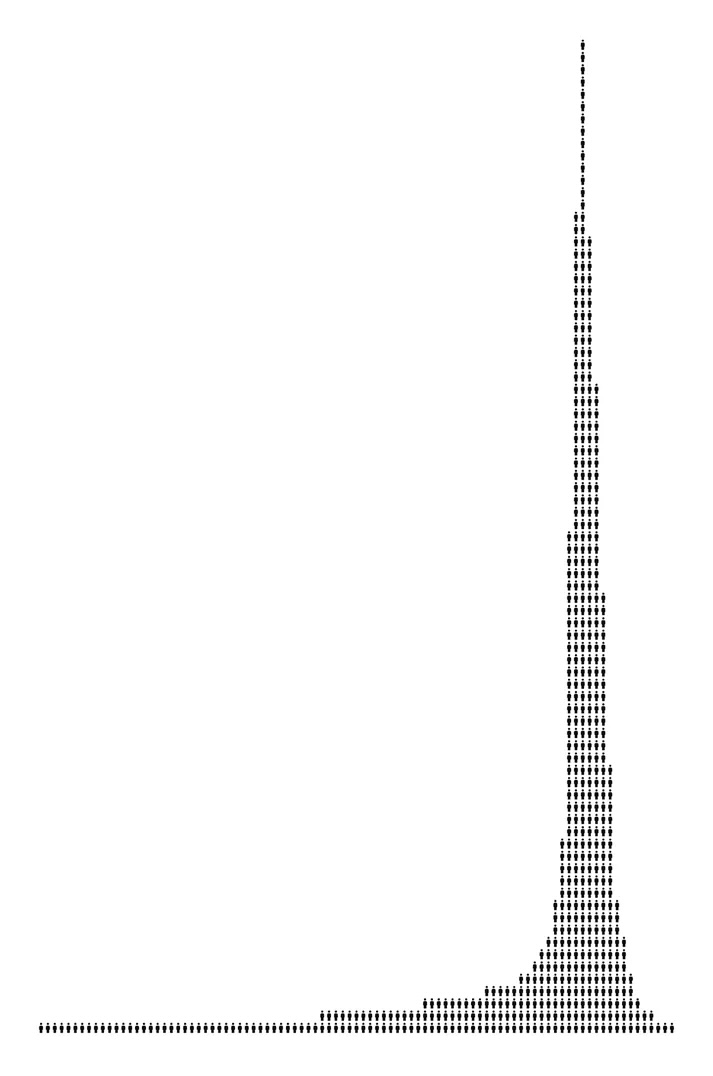

The most striking observation in Dean Spears and Michael Geruso’s new book, After the Spike, is summed up by the cover illustration, which shows a world population rising rapidly to its current eight billion before declining to pre-modern levels and eventually to zero. As the authors observe, this is the inevitable implication of the hypothesis that fertility levels will remain below replacement level indefinitely into the future.

[click to continue…]

{ 90 comments }

The Economist, having surveyed the current state of European higher education, has decided that the most significant problem is that the specialized graduate school where I work is insufficiently “relevant.”

{ 11 comments }

One evening last week, having woken up earlier and, as usual, turned on the Jeremy Vine show (with guest host), I turned, again, to BBC Sounds to find… nothing. They’ve been threatening to turn it off for non-UK listeners for months, pretty much without explanation, and telling users that there is an exciting new and utterly inferior service in which you can just stream Radio 4 and the World Service live. I texted my friend to say it had finally happened, and she said “I know. I immediately deleted the app in anger. Rude”. In fact, it turns out that Radio 2 is available to stream, but this not communicated, let’s say, clearly.

Now to be clear: neither she nor I believe we are entitled to listen for free to radio funded by the UK taxpayer. Being able to listen to pretty much everything whenever I want to has been a huge benefit, for which I would pay a quite large subscription – I’d welcome the ability to do that. But: why have they chosen to withdraw the service rather than to introduce a subscription model? And, for that matter, why don’t they explain why they have withdrawn it and that streaming is still available?

The second question turns out to have an answer. I’ll include a long quote from James Cridland explaining this in detail below the fold. But here’s the short version: the reason they are turning it off is that they are afraid of having to pay worldwide music rights, and they are worried that explaining what they are doing will trigger them having to pay those rights in arrears. And because, in fact, they are continuing to stream the music stations they fear that telling people too clearly how to find them will count as marketing, and thus will trigger having to pay music rights for those streams.

But this leaves me with the first question. The music shows are great but they are essentially ephemeral — I wouldn’t pay a sub for them. By contrast the BBC has a massive archive of spoken word radio that, while intended to be ephemeral is in fact literature that will last forever. It broadcasts this archive on a station called Radio 4 Extra, and most of Radio 4 Extra is (in the UK — it used to be abroad as well) available on demand for a month or so afterwards. As Cridland explains, Radio 4 Extra will still be streamed, but with no catch up, and is not one of the two stations that the BBC makes available through its new (pretty terrible) app. That’s what I, and my friend, would pay our subscription for. And there can’t, surely, be rights issues for 95% of that produce – the BBC (in one of its two forms, see Cridland below) must have worldwide rights forever to obscure thrillers written by Francis Durbridge wannabes in August 1954, no? That output is not affected by the music rights problem (I assume), and could safely be put on catch up (Evidence: good news is that apparently catch up for Radio 4 will be re-introduced in a few weeks).

If anyone with insider knowledge can answer my first question please do, anonymously if necessary. And, any other comments welcome!

Here’s Cridland in full:

{ 43 comments }

The latest podcast produced by the Center for Ethics and Education focuses on political disclosure in the classroom. I think a lot of CTers will find it interesting. Several students were interviewed, and they are quite insightful. For what it is worth, my view is that, in general, when teaching about controversial politically and morally-valenced issues it is usually pedagogically better for most of us not to disclose our substantive views about the issues we are trying to get the students to investigate (I can think of examples of people who do disclose where I think what they are doing is pedagogically superior to withholding in the way I do — Jerry Cohen springs to mind — but I think they are the exceptions). In the podcast my co-director Tony Laden expresses sensible disagreement. Well worth listening to, if I say so myself.

(By the way although I suggested the topic after discussing it with a couple of the students who are featured, as with all our podcasts I take no credit for its excellent quality (both in terms of production values and intellectual content), except in that I suggested to our program manager that she might make podcasts, having no idea quite how good she would turn out to be at doing it. A leading podcaster told me how excellent she thought one of them was, and then was horrified to find out just how much of a shoestring we have been operating on!)).

{ 22 comments }