|

|

| Forthcoming in September, from Basic Books |

As readers of this blog know, Franklin Roosevelt declared he had taken the US off the gold standard on March 6, 1933, as the first substantial act of his presidency. But scholars have not been so quick to accept this date or, with firmness, any other.

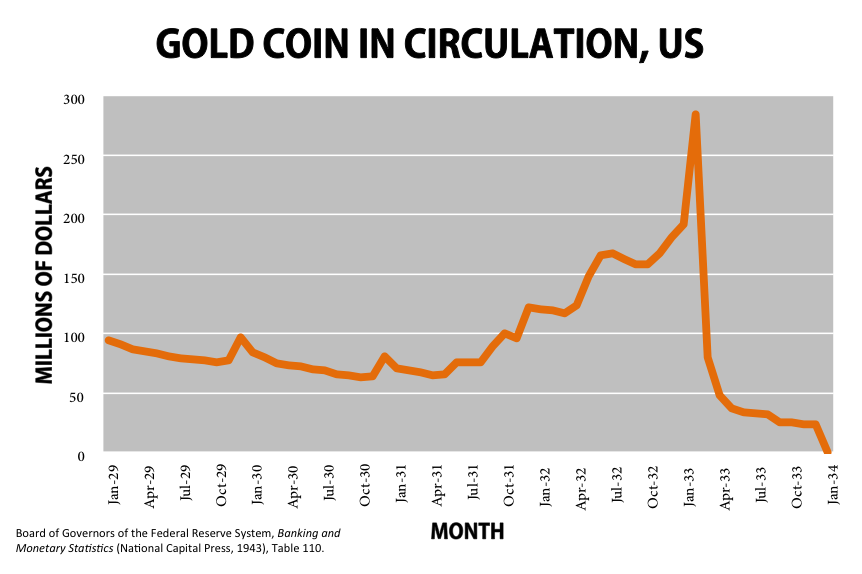

When Roosevelt first said he had taken the US off the gold standard, he didn’t want to make too great a fuss about it because he was trying to quiet a panic that had nearly broken the Federal Reserve System. He hoped Americans would bring their gold back for deposit in the nation’s vaults. And they did. Even though the papers were reporting that the president might issue scrip for temporary currency; even though the Emergency Banking Act provided that Federal Reserve notes could be backed by commercial bank assets, people generally preferred paper money to gold, so long as they trusted the paper money – which, with Roosevelt’s assurances, they did, as you can see from the chart.

You can clearly see the increasing tendency to prefer holding gold during the Depression, culminating in the pre-inaugural panic – followed by a precipitous drop (it occurs almost entirely over the month of March, Roosevelt’s first month in office – at the end of February, there are $284m of gold coin in circulation, and at the end of march, there are $80m). Note that this is before the actual rules against hoarding gold go into effect; it reflects voluntary expression of preference.

But: although gold largely went out of domestic US circulation in March 1933, the world value of gold in dollars, though it took a slight spike up on Roosevelt’s inauguration, settled back down to the statutory rate, of about $20.67 to an ounce. Which meant no price rise for US farm commodities.

So in the middle of April, Roosevelt took further action. On April 19, he said he would back legislation permitting him, as president, to conduct his own monetary policy – to issue greenbacks, or to change the gold value of the dollar, and he said the US would no longer export gold. On April 20, he issued an executive order implementing the ban on exports.

We have, then, two (well, two-ish) moments at which the US could be said to have gone off the gold standard: March 6 and April 19-20.

Which was it?

First, there is the question of what Roosevelt thought he was doing. On March 6, he told aides, “We are now off the gold standard.” On April 18, he told aides – “with a chuckle” – that once he announced the embargo and the new legislation, the US would have “definitely abandoned the gold standard.” So the US was off on March 6, and then definitely off on April 19.

Roosevelt’s “definitely” began a long tradition of adverbs deployed to qualify his monetary actions in April 1933. On April 20, the New York Times echoed Roosevelt, reporting the president’s actions of April 19 were “taking the United States definitely off the international gold standard.” Writing in 1939, G. Griffith Johnson concurred: “The United States was now definitely off the gold standard.”2

But even the “definitely” camp were somewhat indefinite as to when this definite action happened. For example, Arthur Whipple Crawford in 1940 said it was not the president’s announcements of April 19, but the order “of April 20 by which the gold standard was definitely abandoned.”3

The distinction between the two days may seem a slight one. On April 19, the president said he would back the inflation legislation and start a gold embargo, and on April 20, he issued an executive order implementing the gold embargo. But the inconclusive state of scholarship on which of the two dates definitely marks the end of the gold standard blurs the definition of the April 19-20 decision.

Nor is “definitely” the only adverbial way to qualify what occurred. One hard-headed, quantitative study of the world price of gold in the early 1930s goes for litotes: “Before April 20, 1933, we were not unmistakably off the gold standard,” indicating that before that date a reasonable observer could be mistaken on this point. A recent, authoritative account of the Roosevelt presidency has it that “Roosevelt on April 19 officially took the United States off the gold standard,” suggesting the existence of a condition in which a nation can be unofficially off the gold standard.4

Some scholars use a different adverb, writing with apparent relief that by April 19, “The United States was finally off the gold standard,” or that “On the twentieth [of April] the President finally took the nation off the gold standard[.]” The use of “finally” indicates that whatever happened during the previous weeks, it was not until April 19 (or 20) that the process of taking the US dollar off gold had at last ended.5

The “finally” camp have allies in a group of historians who indicate that there was an extended process of taking the US off the gold standard. Charles and Mary Beard inaugurated this tradition in their 1939 analysis, saying that Roosevelt “gradually” took the nation off gold – though the Beards further qualify this statement by adding, “in some respects.” Another recent survey says that with the April embargo “It became clear that the temporary escape from gold might represent a new policy entirely” – indicating, without explicitly saying, that the process from March to April was one of clarifying and publicizing a decision Roosevelt had already made.6

As for Roosevelt himself, having flatly declared that the US was off the gold standard on March 6, and that in any case it would definitely be off the gold standard by April 19, the president himself took a third shot at the subject in 1934 with his book On Our Way. Now he shifted to a third date and a different adverb, writing in a section titled with apparent confidence “The United States Goes Off the Gold Standard,” that neverthless “Many useless volumes could be written as to whether on April twentieth the United States actually abandoned the gold standard.”7

No wonder one trio of economists embraced poetry rather than choose a date, saying the US went off the gold standard “about crocus-daffodil time, 1933.” With crocuses coming earlier than daffodils, and breaking earth at different times in different climes, this formula may perfectly capture the imperfect condition of American monetary policy in the first spring of Roosevelt’s presidency.8

One may ask whether I am not fulfilling Roosevelt’s prediction and producing useless volume (if not volumes) on the question of when the US went off gold. I do think it matters. If Roosevelt did not know what he was doing and felt or blundered his way to a policy, then his actions are much less worthy of study and emulation than if knew what he was doing, and began a successful course on March 6 that concluded on April 19 (or 20).

1This legislation was known, somewhat confusingly, as the Thomas Amendment. “Thomas,” after Elmer Thomas, the Oklahoma Senator who wrote the original version of the legislation, even though Roosevelt, with his aides, drafted the version that actually went to the floor. And “Amendment” because it was an amendment to the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1933, which is better known for inaugurating a system of price subsidies by a processing tax, but which also included this legislation as its Title III.

2“President Takes Action,” NYT 4/20/1933, p. 1; G. Griffith Johnson, The Treasury and Monetary Policy, 1933-1938 (1939; New York: Russell and Russell, 1967). The NYT also uses “publicly” in this story, acknowledging that the president had privately said the US was already off gold.

3Arthur Whipple Crawford, Monetary Management under the New Deal: The Evolution of a Managed Currency System; Its Problems and Results(1940; New York: Da Capo, 1972). Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. is also a “definitely” user.

4Bertrand Fox, “Gold Prices and Exchange Rates,” Review of Economics and Statistics 17:5 (August 1935): 72-78; David M. Kennedy, Freedom from Fear: The American People in Depression and War (Oxford University Press, 1999).

5Anthony Badger, FDR: The First Hundred Days (Hill & Wang, 2008); James Daniel Paris, Monetary Policies of the United States, 1932-1938 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1938).

6Charles A. and Mary R. Beard, America in Midpassage (Macmillan, 1939); Eric Rauchway, The Great Depression and the New Deal: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press, 2008).

7Franklin D. Roosevelt, On Our Way (New York: John Day, 1934).

8F. A. Pearson, W. I. Myers, and A. R. Gans, Pearson, “Warren as Presidential Adviser,” Farm Economics 211 (December 1957): 5597-5676. Barry Eichengreen says in Golden Fetters that Roosevelt did not even mean to take the dollar off gold until April because at his first press conference, “Roosevelt asserted that the gold standard was safe.” Eichengreen relies for his account of this press conference on Johnson, but as we have seen, Johnson’s account is wrong.

{ 29 comments }

Rich Puchalsky 03.18.15 at 8:26 pm

“If Roosevelt did not know what he was doing and felt or blundered his way to a policy, then his actions are much less worthy of study and emulation than if knew what he was doing, and began a successful course on March 6 that concluded on April 19 (or 20).”

There’s a whole world of assumptions in that sentence. I don’t get thee impression that you really believe them, but rather that you want to write a book about this and you’re worried about justifying it.

For the record, if he felt or blundered his way to a successful policy, that’s a lot more worth studying than if he had an easily summed up plan and carried it out.

William Berry 03.18.15 at 9:05 pm

“For the record, if he felt or blundered his way to a successful policy, that’s a lot more worth studying than if he had an easily summed up plan and carried it out.”

Well, that sort of elides the “worthy of . . . emulation” part.

john c. halasz 03.18.15 at 9:06 pm

Eric:

Thanks for these posts. I’ve found them quite interesting, in filling out my back-ignorance. And I think they are basically right. For those who self-righteously say that the U.S, has never defaulted on its public debt, the re-pegging of the $ to gold is a significant contrary indicator. And likewise, it might have been the most significant measure taken by the FDR administration to foster economic recovery, since deficit spending in Keynesian fashion was resisted by FDR himself and never amounted to the levels that would have been required, (even if the work relief measures were humane and successful). (Sweden and Nazi Germany had their own reasons for deficit spending, though neither were exactly Keynesian in their rationale). On the other hand, Bruce Wilder, who is much more knowledgeable than me about these economic- historical matters, might well be right that institutional/structural reforms were a key part of what was accomplished by the New Deal, regardless of fiscal failures or insufficiency.

This is a bit OT, but fun, a reel in favor of “farm aid”, (which I take it meant the Agricultural Adjustment Act from Henry Wallace), by the Boswell sisters, the original swing-era tight, hep harmony gal group, who were really better than all their imitators. It’s so full of bad jokes that it’s hard to tell whether it was a piece of New Deal propaganda or a parody of the same:

Rich Puchalsky 03.18.15 at 9:13 pm

All right then, I would rather have politicians emulate the qualities of successful blunderers (if there is any skill there that it is possible to emulate) than those of successful policy followers, given that the second skill is fairly common and is not applicable to most political actions and the first is rare and is needed almost all the time.

ZM 03.18.15 at 9:51 pm

If you want to be more polite you could say he was a policy improviser, after the idea of moral improvising, using practical judgment

Bruce Wilder 03.18.15 at 11:46 pm

If we are voting on whether FDR’s monetary policy was a series of lucky blunders or methodical and systematic, I would unequivocally endorse the latter view.

The rhetorical game of whether the U.S. was on or off gold wasn’t a matter of classroom semantics; it was part of the political process and FDR was certainly aware that many, who favored a gold standard as the anchor of policy, did so with a religious zealotry, née fanaticism. There was no political profit to FDR in making a definitive statement and holding fast to it with regard to being “on” or “off” the gold standard, even if — especially since — he was systematically dismantling the gold standard. It could only arouse and aid the gold bugs, for whom the symbolism of being “on” or “off” was all-important.

Operationally, a gold standard policy has several elements, which may vary in details, and FDR was clearly well-briefed on those details. This should not be surprising. The gold standard had animated American politics for more than 60 years, helping to define the partisan division between the Parties. Establishment of the Federal Reserve system, after the failure of Republican proposals, had come early in Woodrow Wilson’s first term, when Wilson, a former Bourbon (“Gold”) democrat had convinced William Jennings Bryan of its advisability. And, the country’s economy had been swirling the deflationary drain created by adherence to the gold standard for three long painful years marked by repeated bank runs and sometimes rapid economic contraction.

From our perspective, getting off gold seems like a no-brainer, but to contemporaries it had seemed for some time a treacherous policy move, likely to strike a potentially fatal blow to confidence if handled badly. Irving Fisher, among others, had detailed the necessary steps, and hazards, bringing an end to U.S. adherence to the gold standard.

In the March 8 news conference, the transcript you linked in the previous post, Roosevelt’s money policy, 1933-1934, Roosevelt read aloud from a newspaper article of the previous evening, by the New Deal critic, Ralph Robey. By way of preface, FDR said, “It is pretty good. It doesn’t say whether we are on or off it.”

Robey’s article, as read aloud by FDR, named four elements of a gold standard, and FDR confirms that only one of those elements had been abrogated on March 6.

Robey’s four requisites of a gold standard were:

1. A gold coin of fixed gold content and unit of currency value;

2. Free coinage of gold;

3. Convertibility of paper currency and gold at fixed rates or par;

4. Free import and export of gold with other nations.

FDR in his remarks on March 8 seems to me to confuse 3 and 4 a bit, asserting that as of March 6, the U.S. no longer had free trade in gold. And, on March 10, his order authorizing the re-opening the banks would explicitly prohibit all export of gold coin or bullion except under license from the Secretary of the Treasury

The hammer would fall again on Robey’s number 1, 2 and 3 on April 5, with Roosevelt’s Executive Order 6102, taking gold out of commercial circulation by demanding that all gold coin and bullion be cashed in by May 1, 1933. The April 20 order would supercede the April 5 order, but also reiterate it.

And, so it continued, the policy hammer falling again and again in a steady pattern of blows, from the President and from the Congress. The April 20 order would be superseded and reiterated again on August 28. And, Congress weighed in repeatedly, ratifying the President’s actions or extending new bases for Presidential action.

In an important sense, this is how policy operates, how policy must operate, when habits long established must be broken. Constant re-iteration and tweaks to overcome small, potentially valid objections or clever attempts at circumvention.

And, in harmony with the chords struck in steady rhythm of the falling hammer, there was a fog, a dust cloud of ambiguity thrown up as well about what shape the future might take, about what all these emergency measures might mean in toto, once the emergency had passed.

The Thomas Amendment, which the Administration would use sparingly, but to good effect, exemplified the incoherence of political rationales surrounding the policy being implemented by FDR. Here’s the Wikipedia summary of what it called for: The President, in response to an emergency can

From a Plains Populist — the eponymous Thomas — this was 1890s Silver standard inflation backing up the 1920s innovation, the New Economy FOMC. It is not a theoretically coherent vision, but it authorized FDR to act and dressed up potential policy in familiar ideological clothing for different generations. And, not incidentally, to take actions to flank any tendency to fall back on a Silver standard, whether as a result of the World Economic Conference in July 1933 or a revival of populist instincts among Democrats in the U.S.

FDR, characteristically, embraced and discarded definite labels quickly, eager for the support that a label might garner, but wary of that a definite positive label or ideology might allow a political opposition to mobilize. “Managed currency? Yes. Only no. “Inflate?” How about “reflate”?

Personally, I would not say that the U.S. was finally, permanently “off” the gold standard until January 31, 1934, when the Gold Reserve Act took effect, ratifying all the previous executive orders and FDR raised the nominal price of gold to $35/ounce. It was a brilliant bit of political legerdemain, to put a period to nearly a year’s worth of policy blows against the gold standard by symbolically pegging the dollar’s value to gold once again, but with no operational support.

Even that wasn’t the end: gold continued to have a fantastic superstitious effect. The desire to “sterilize” the surging imports of gold from Europe played a role in the disastrous policy contraction of 1937.

maidhc 03.19.15 at 5:12 am

john c. halasz: That’s an interesting film. The songs are not too exciting, but the performance is up to the usual Boswell standard. Most of the other Boswell films have Connie sitting next to Martha at the piano, with Vet standing behind. This was their usual performing setup, to hide the fact that Connie couldn’t walk. In this film they have different setups. Connie’s disability is not obvious despite their moving around the set.

Eric 03.19.15 at 9:52 am

Bruce Wilder – I think/hope you’re going to like the book.

Bruce Wilder 03.19.15 at 2:28 pm

I expect I will like the book.

djr 03.19.15 at 2:55 pm

The gold standard is Schrödinger’s cat. We can’t observe the wave function directly, we can only see the result of a measurement process, in this case when someone asks to trade paper currency for gold at the statutory rate. If nobody looked in the box between 6 March and 20 April 1933, it’s not meaningful to talk about whether the US was on or off the gold standard at that time.

john c. halasz 03.19.15 at 7:14 pm

@6:

“The desire to “sterilize†the surging imports of gold from Europe played a role in the disastrous policy contraction of 1937.”

Could you elaborate a bit on that. I take it trade and financial surpluses were coming in, which were stall at least partly settled in gold still. But how would have that effected the $ money supply, once it wasn’t convertible privately to gold? And here I thought that FDR and Eccles were just worried about the upcoming wave of CIO strikes.

Bloix 03.19.15 at 11:56 pm

#11-

“The Fed’s contractionary policy was complemented by the Treasury’s decision, in late June 1936, to sterilize gold inflows in order to reduce excess reserves. The sterilization policy severed the link between gold inflows and monetary expansion. By preventing gold inflows from becoming part of the monetary base, this policy abruptly halted what had been a strong monetary expansion. Friedman and Schwartz (1963, 544) maintained that “The combined impact of the rise in reserve requirements and—no less important—the Treasury gold-sterilization program first sharply reduced the rate of increase in the monetary stock and then converted it into a decline.†…

“The recession ended after the Fed rolled back reserve requirements, the Treasury stopped sterilizing gold inflows and desterilized all remaining gold that had been sterilized since December 1936, and the Roosevelt administration began pursuing expansionary fiscal policies. The recovery from 1938 to 1942 was spectacular: Output grew by 49 percent, fueled by gold inflows from Europe and a major defense buildup.”

http://www.federalreservehistory.org/Events/DetailView/27

To understand what this means you need to be aware that until 1945 the Federal Reserve district banks were required to hold a gold reserve of 40% (either in gold or in certificates backed 100% by gold held in the Treasury) to back their federal reserve notes. (In 1945 the percentage was reduced to 25% and in the mid-1960’s it was eliminated.)

Gold that was “sterilized” was gold that was not permitted to be used to back gold certificates issued to the district banks.

LFC 03.20.15 at 1:13 am

I would be interested in Eric R.’s (or others’) comments on how, if at all, this aspect of FDR’s policies relates to the evaluation of other aspects of his presidency.

In school I read Warren Kimball’s The Juggler, about FDR’s foreign policy. My recollection of the book is not esp. fresh (and for (bad, in retrospect) reasons I have parted w my copy). But what I seem to recall is that Kimball argues that a lot of FDR’s foreign policy was on-the-fly improvisation: sometimes it worked pretty well, sometimes not so much. From these posts on his monetary policy (which I’ve read, well this second one at any rate), I get the impression that in this area there was more calculation, if sometimes cleverly disguised, and less improvisation.

My other, somewhat related observation is about FDR’s ability to grasp this stuff and its implications, an ability he apparently had. I’ve never thought of FDR (though of course I cd be wrong on this) as an esp. detail-oriented president. He had an ‘elite’ education but was, at least as far as I’m aware, not a towering intellect (Geoffrey Ward’s Before the Trumpet, which I’ve read parts of, suggests as much, and presumably the sequel volume, A First-Class Temperament, does as well; perhaps not all historians agree about this, I don’t know). I guess you don’t have to be brilliant to easily grasp monetary policy, just have to have a certain kind of mind…?

Harold 03.20.15 at 1:36 am

Everyone seems to agree that FDR was not especially brilliant in the conventional sense. However, FDR apparently had a very good memory and was able to retrieve, synthesize, and relate to each other various seemingly disparate facts, at least that was the conclusion of the author of a standard biography I read some years ago (forgotten which one). Also, unlike many people in positions of power he was neither intimidated nor threatened by intelligent, knowledgeable people.

LFC 03.20.15 at 1:45 am

Harold:

that makes sense, thanks

john c. halasz 03.20.15 at 2:57 am

Bloix @12:

Thanks for that. Though it doesn’t quite answer the puzzle, since operational monetary measures, e.g., raising reserve requirements, sufficed to “sterilize” gold inflows and it’s not clear how gold inflows would have necessarily expanded $ money supply.

My rough understanding is that the New Deal policies resulted, in somewhat hit-or-miss fashion from an alliance of elite Progressives, originally from both parties, populists, American Institutionalist economics, and some understanding of debt-deflation dynamics from the likes of Fisher and Eccles. There wasn’t anything especially Keynesian about it and it wasn’t sufficient in such terms. And that FDR had always run on the standard “balanced budget” fetish. However, given modern post-Keynesian understanding, large CA surpluses meant foreign dis-savings or net spending and thus at least one of the domestic sectors must have been forced into net saving, which, under the circumstances, wouldn’t have been the domestic household, nor the domestic private business sector. So perhaps, however unawares, the government sector was forced to respond, putting a limit on fiscal expenditure, however otherwise desirable. The 1937-38 steep recession is usually presented as a failure of the New Deal, which otherwise would have more successfully resolved the crisis and the debt over-hang, such that it was only the outbreak of WW2, which unleashed the government coffers and allowed the repair of private sector balance sheets. But perhaps the foreign balances played a larger role, independent of any remaining residue of the “gold standard”.

Harold 03.20.15 at 5:05 am

Now I remember, it was called “Franklin Roosevelt: a First Class Temperament”. In retrospect I feel the premise was somewhat patronizing, but it was interesting at the time.

Harold 03.20.15 at 5:17 am

God, I read that book 26 years ago when it first came out! And Ward’s assessment of the quality of Roosevelt’s intellect is literally the only thing I remember about it.

LFC 03.20.15 at 2:18 pm

Harold:

Actually I referenced it in my comment @13. ‘First-Class Temperament’ was a sequel to Ward’s ‘Before the Trumpet’ (I’ve read some of the latter). The title comes from a quotation from someone (I don’t know who) who characterized FDR as having a second-class intellect but “first-class temperament.”

Harold 03.20.15 at 6:31 pm

My apologies, LFC, for not absorbing your entire post until after I posted mine. I had completely forgotten where I had read that characterization of FDR’s intellect until I googled the phrase “first class” which had lodged somewhere in my brain. At the time I read that book I had read virtually nothing about Roosevelt or the New Deal, although my parents had been fans — not my grandparents, though. They liked TR.

Bruce Wilder 03.20.15 at 10:41 pm

john c. halasz @ 16

In the previous thread, someone provided a link to Christina Romer’s work, which has assumed the status of conventional wisdom for today’s New Keynesians, to the effect that inflows of gold from Europe supplied the monetary stimulus that New Keynesian theory blesses as the canonical true and potent financial conduit for stable expansion. As you say, it makes absolutely no operational or mechanical sense, but she dresses her thesis up in econometric clothing of the right cut and fit for people for whom the Great Moderation was the end of history.

As I remarked in the other thread, the RBC folks have Cole and Ohanian, who do the same sort of econometric ritualizing, to legitimate an even more delusional story: that Hoover (!) and FDR made the Great Depression (worse) out of policies that increased wages and cartelized prices. The economics profession has been dancing around the maypole of wage rigidity since the first neoclassical synthesis of the 1950s, so many economists are well-prepared to nod uncomprehendingly. The National Industrial Recovery Act and its cartels are a particular bogey man for most economists today, as are the Agricultural Adjustment Acts (1933, 1938, and the related acts of 1935).

Friedman and Schwartz produced the most influential (for economists) story of the genesis of the Great Depression as part of their monumental history, but the story they tell is almost entirely counterfactual: it isn’t an explanation of what did happen, so much as a story of how it could have happened differently if a different kind of conservative policy had been implemented. And, that different kind of policy — a conservative inflationist policy — was the blueprint that Bernanke developed over his career and applied in the crisis of 2008.

How it actually happened, of course, is that the bankers at the Federal Reserve did what they thought they should do, under the Gold Standard, and Hoover, more or less, did what he thought he should do, in terms of Progressive cheerleading and fiscal rectitude and “responsible” laissez faire.

Bloix, in his comment, covered how the continued influence of gold standard psychology contributed to motivating Federal Reserve policy in the 1937 debacle. Policymakers did what they thought they should do — including FDR himself — because they had a view of moral power, which was disconnected from operational consequences. At base, it is not unlike the thinking that inspires the politics of a cargo cult.

It’s those moral imperatives — often deeply held and like many ethical strictures, with only a spiritual, not a coherent mechanical connection to consequences — that makes narrative analysis problematic. If an historian writes a military history and judges a general’s strategy mistaken, it is really not difficult to both relate the general’s point-of-view and outline actual military operations and outcomes, without violating a partisan’s sense of reality. No matter how fervently a neo-Confederate might imagine a Gettysburg, where Pickett’s Charge succeeds, he’s not likely to remain unaware of who won that battle in fact and how.

It isn’t just that military science is more advanced than economic science, though the benighted state of economics is a factor. People experience the economy as a set of phenomena akin to the weather: something complicated and chaotic everyone talks about, but about which little can be done (aside from an occasional sacrifice to the rain god!). Except that everyone has to be an economist in the same sense that everyone has to be a psychologist — everyone has to be able to function in society, to pull the levers the economy as an institutional system, provides. It is only the economist qua technocrat, who has a specialized and alien perspective, potentially at odds with the intuitions of the ordinary worker or businessman. Whether it is enough for the economist-qua-technocrat to be initiated into esoterica and to preach, divine the future or fulfill other public duties of a civic priesthood, or whether they actually have to know enough to operate the machinery remains an open and debatable question.

In 1933, the idea of technocracy as a solution was open-ended and plausible in a way that, maybe, it isn’t today. FDR was born in 1882, Keynes a year later (and a few months after Marx died). The 1880s was also the period when the modern, corporate economy was born, when the great national trusts formed, precursors to the industrial corporations that would be formed in the 1890s, beginning with General Electric. The New Economy of the 1920s and these major figures had grown up together — they were exact contemporaries. The Gold Standard had caused the previous Great Depression, and ruined the Populists and the Democratic Party in the 1890s, when FDR was just entering his teens. He didn’t have to have the deep theoretical understanding of a devotee of MMT; he understood the politics, and helpfully, so did his Party, in a deep visceral way.

Reactionary adherence or attraction to gold standard principles is an endemic disease of the human soul and it is not enough to treat the symptoms, or effect a cure in one instance; there must be a political inoculation against recurrence. That’s where I see FDR’s political genius at work: he left just enough vestigia to prevent a gold standard party from forming to campaign for restoration — like the Whig invention of constitutional monarchy, it prevented a recurrence of the disease.

LFC 03.21.15 at 1:26 am

Harold:

Apology is completely unnecessary. (My parents and many of their friends were New Deal Democrats, if I had to pin one label on ’em. My parents had their children relatively late in life — certainly by the standards of their generation, at any rate. So I was born in the latter part of the Eisenhower era but my parents and their friends came of age politically when FDR was in office.)

john c. halasz 03.21.15 at 6:34 am

Bruce Wilder @ 21:

Actually, I was inquiring specifically about what was happening in 1937-38, and whether there was an alternative policy. The “gold standard” wasn’t a real issue then, since “sterilization” mechanisms could accommodate gold inflows, but, given a Wynne Godley simple 4 sector model of national income accounting, (which didn’t exist back then), whereby the the 4 sectors must, by accounting identity, resolve to zero, gold or no gold, wouldn’t the CA surpluses, whatever the operational/institutional details, have “forced” net savings onto the government sector, assuming the private sectors were not in a position to net-save? I am aware of the impressive decline in total debt/GDP ratio once the New Deal took hold, but I don’t know the price/wage level data. Obviously, “high” levels of inflation took hold after FDR, but they were really reflation from a severely depressed/deflated economy. So just why was further “inflation” perceived to be a problem, (since I suspect that the data would show that the price/wage level hadn’t yet reached pre-depression levels). Further inflation, provided wage/price levels kept up, would have served to continue to burn away debt burdens, but the capacity of either domestic private sectors or the foreign sector to absorb government debt, i.e. to begin net-saving when net-spending was required, might have been limited. And the continuing shadow of gold might have limited the possibility of devaluing with respect to foreign trade surpluses, which higher domestic inflation might have achieved in its absence. I remain puzzled by all this.

Peter T 03.21.15 at 6:49 am

“Reactionary adherence or attraction to gold standard principles is an endemic disease of the human soul”. It’s not just reactionaries, although it strikes those with particular force. Money is simultaneously a general debt and a unit of account. Debt is notoriously uncertain: it may be that one’s creditors cannot pay, or it may be that they will not pay. Gold sets up a standard which does not hold the upper classes hostage to politics – that is its attraction. But the lure of certainty, of an anchor in a sea of doubt, exerts a strong force on intellectuals. Hence many of the convolutions of economics.

bob mcmanus 03.22.15 at 8:51 pm

Just in passing, since the thread seems to have slowed down, I thought I might paste a paragraph from my current reading, Junji Banno, The Political Economy of Japanese Society, article “The Wartime Institutional Reforms and Transformation of the Economic System” by Okazaki Tetsuji

Consider it an unformed and uninformed question, in response to Wilder, Halasz, and Rauchway’s entirely domestic, institutional, and even psychological analysis of 1937.

Immanent war, re-armament, and massive disruptions to global trade and currency balances were in plain sight in 1937.

bob mcmanus 03.22.15 at 9:27 pm

I do have a book or two on 1930s Japan-US trade to be read, but can’t find much on the web that I didn’t already know.

“In truth, the United States did not want to disrupt its lucrative trade with Japan. In addition to a variety of consumer goods, the U.S. supplied resource-poor Japan with most of its scrap iron and steel. Most importantly, it sold Japan 80% of its oil.”

I suppose the question is how important the Japan/Asian trade was to the American economy, balance of payments, currency values etc to see if the Japanese measures of 1937 would have had any effect on the US economy, with predictable future effects. And other global factors of course.

But maybe it was just “Reactionary adherence or attraction to gold standard principles is an endemic disease of the human soulâ€

bob mcmanus 03.22.15 at 11:31 pm

Halasz does approach the foreign exchange/trade situation in comment 23

Things I have looked up.

1) Washington State was a major port for the export of scrap steel to Japan

1a) Not sure what inflation would have done to scrap steel prices in 1937-38, when the Japanese were inflating, but I would guess Washington State knew

2) Came across a Washington state politician, I think in 1940 saying something like “China isn’t our business, scrap steel is our business”

3) Washington State had two freshman Democratic Senators in 1937, owned that state thereafter but these were party flips, and maybe these Senators didn’t feel so secure. Looks like maybe a change from agriculture to industry.

4) 69-71 Senators sure is nice, but the ability to resist a filibuster is also the ability to override a veto. FDR vetoed a lot.

5) Steel Workers struck hard in 1937, and the Longshoreman Strike of 1934 is legendary. Bridges was radical.

In general abstract and weird, without benefiting by hindsight, whether it would be all that wise to inflate in 1937, not having complete certainty as to what would happen when overseas. Probably didn’t want steel mills shutting down. Especially since the political will to fix it if the economy went pear-shaped with double-digit inflation was completely lacking. America wasn’t exactly ready for a command economy, and overseas wars wouldn’t yet sell it.

Maybe a certain cushion and reserves were a good idea.

Enough from me. I don’t even know how to do history, I guess.

Matt 03.23.15 at 12:24 am

Washington state was pretty agricultural before the 1930s, though the aircraft business that became Boeing had already been established in Seattle for two decades by 1937. The government construction of hydroelectric dams in the 1930s gave the state a vast amount of inexpensive electric power and attracted new industries. Electricity intensive materials like aluminum and magnesium were produced in large quantity during the war and after. Today Washington still has the cheapest electricity in the US and some of the cheapest in the world. It still draws businesses that are sensitive to electricity prices: large data centers, steel recycling, and manufacturing materials like aluminum, carbon fiber, and purified silicon.

The next big industrial boost came in secret in the 1940s: the construction of the Hanford plutonium facility in the eastern part of the state. It poured billions of dollars and an army of well paid workers into what had been a sleepy agricultural region. The small farming community that had been present in 1940 was largely bought out and relocated by fiat. For its first decade or so the town nearest Hanford operated much like one of the secret Soviet “atomic cities.” You had to have permission to live there and almost everyone in the area had a Hanford-related job. Today Hanford is still the largest employer in the region though it hasn’t made plutonium since the 1980s. The army of cleanup workers will labor until the 2050s. Weapons of mass destruction: the rare Keynesian stimulus program worse than literally burying and digging up bottles of currency!

Bruce Wilder 03.23.15 at 3:09 am

Re: 1937

It seems to me like the fiscal and monetary policy initiated in 1936, which had such severe consequences in 1937-8, was a mistake. Policymakers were not responding to pressures, at least not to pressures independent of their own misapprehensions, and they did not have the understanding necessary to anticipate the consequences of what they did.

The Fed and Treasury, as I understand it, were concerned that ballooning bank reserves were an indication that the Federal Reserve was losing its control over the banking system, because constraining and providing bank reserves was thought of as the major conduit for the Fed’s power. They may have fancifully imagined the dam breaking on those bank reserves, and a wild ride of speculative bank lending following, with no means for the Fed to discipline the financial sector — I don’t know. I also don’t know that they were actually acting, as they would in the post-WWII period, to dampen incipient inflation. Most important, they didn’t have the tools — like Hicks/Keynes IS/LM analysis — that might warn them about how the effect of what they did could be amplified by the changing course of fiscal policy. Between FDR reining in relief and public works spending and the actions by the Fed, both heartily endorsed by Henry Morgenthau, Jr. no doubt, policymakers set off the mother of all inventory cycles.

The flow of gold from Europe was a kind of fiscal stimulus spending that the central bank could accommodate, without the Federal government running an increased deficit and issuing even nominal debt. Calling it a “monetary expansion” is ideology, but not my ideology.

Keynes’ theory was an elaboration of a stagnationist thesis that didn’t make much sense, applied to the U.S. struggling to cope with the myriad innovations of the New Economy of the 1920s and very rapid increases in productivity in agriculture and manufacturing. It is worth noting that wages in manufacturing continued to rise thru the recession of 1937-38, and that Congress responded to the crisis by passing an expanded and elaborated Agriculture Adjustment Act of 1938.

Comments on this entry are closed.