From the category archives:

Academia

Announcements from major employers, including Amazon and Tabcorp, that workers will be required to return to the office five days a week have a familiar ring. There has been a steady flow of such directives. The Commonwealth Bank CEO, Matt Comyn, attracted a lot of attention with an announcement that workers would be required to attend the office for a minimum of 50% of the time, while the NSW public service was recently asked to return to the office at least three days a week.

But, like new year resolutions, these announcements are honoured more in the breach than the observance. The rate of remote work has barely changed since lockdowns ended three years ago. And many loudly trumpeted announcements have been quietly withdrawn. The CBA website has returned to a statement that attracts potential hires with the promise, “Our goal is to ensure the majority of our roles can be flexible so that our people can work where and how they choose.”

The minority of corporations that have managed to enforce full-time office attendance fall into two main categories. First, there are those, like Goldman Sachs, that are profitable enough to pay salaries that more than offset the cost and inconvenience of commuting to work, whether or not they gain extra productivity as a result. Second, there are companies like Grindr and Twitter (now X) that are looking for massive staff reductions and don’t care much whether the staff they lose are good or bad.

Typically, as in these two cases, such companies are engaged in the process Cory Doctorow has christened enshittification, changing the rules on their customers in an effort to squeeze as much as possible out of them before time runs out.

We might be tempted to dismiss these as isolated cases. But a recent KPMG survey found that 83% of CEOs expected a full return to the office within three years. Such a finding raises serious questions, not so much about remote work but about whether CEOs deserve the power they currently hold and the pay they currently receive.

In an article published last year, I tried to show that our moral judgement is heavily biased when it comes to migration. For instance, an action that we regard as a minimum moral obligation towards compatriots becomes, towards migrants or foreigners, non-obligatory and even forbidden. I tried to show that even ethicists well disposed towards foreigners – cosmopolitans, so to speak – suffer from the same bias. Nationalism stifles creativity to such an extent that we are often unable to imagine doing to foreigners what it is a minimum moral obligation towards compatriots.

A new example is given by the US election campaign. [click to continue…]

Like most academics these days, I spend a lot of time filling in online forms. Mostly, this is just an annoyance but occasionally I get something out of it. A recent survey in which the higher-ups tried to get an idea of how the workforce was feeling, asked the question “Do you think of the University as We or They?”.

In response to my previous post on the imminent threat to Dutch universities to have their budgets cut with up to 1 billion euros a year, I received a few emails from (mainly younger) staff to ask how they could contribute to the protests.

In response to my previous post on the imminent threat to Dutch universities to have their budgets cut with up to 1 billion euros a year, I received a few emails from (mainly younger) staff to ask how they could contribute to the protests.

I will respond specifically for the current Dutch case, but I think we could learn from international experience here. So if you have additional thoughts on what university staff could do to make sure the material conditions in which they need to do their work are adequate (and for public universities this means not having their public budgets cut in a way that creates inadequate funding), then please do share your suggestions.

[click to continue…]

On Monday, the first day of our academic year, I went to a demonstration. The reason for the demonstration are the announced budget cuts for higher education, which our new right/extreme-right government wants to implement. The figures aren’t set in stone yet, but the financial appendix that was presented when the new government took office suggests that there will be a direct cut to the budget of higher eduction of 150 million euros in 2025, and increasing up to almost 1 billion a few years later (I read somewhere that this is equivalent to the size of one Dutch public university). The cuts would come in different ways – some are reversals to budget-increases that were made by the previous Minister (the renowned scholar Robbert Dijkgraaf who left his prestigious job in Princeton to serve as our minister of education); there are also indirect cuts because the government plans to reduce the number of international students (which will lower revenues for universities); and general cuts to HE. The government will also lower the payment universities gets for a student that takes too long to finish their undergraduate degree, and then expects the students to pay much higher fees. Importantly, the previous government made a Bestuursakkoord (a sort of ten-year contract) with the public universities, which this new government now modifies significantly, without agreement from the universities.

On Monday, the first day of our academic year, I went to a demonstration. The reason for the demonstration are the announced budget cuts for higher education, which our new right/extreme-right government wants to implement. The figures aren’t set in stone yet, but the financial appendix that was presented when the new government took office suggests that there will be a direct cut to the budget of higher eduction of 150 million euros in 2025, and increasing up to almost 1 billion a few years later (I read somewhere that this is equivalent to the size of one Dutch public university). The cuts would come in different ways – some are reversals to budget-increases that were made by the previous Minister (the renowned scholar Robbert Dijkgraaf who left his prestigious job in Princeton to serve as our minister of education); there are also indirect cuts because the government plans to reduce the number of international students (which will lower revenues for universities); and general cuts to HE. The government will also lower the payment universities gets for a student that takes too long to finish their undergraduate degree, and then expects the students to pay much higher fees. Importantly, the previous government made a Bestuursakkoord (a sort of ten-year contract) with the public universities, which this new government now modifies significantly, without agreement from the universities.

There was a real sense of defeat among the participants at the demonstration that I talked to, which I also sense very strongly. Why? [click to continue…]

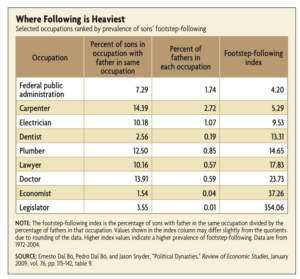

This study showing that US academic faculty members are 25 times more likely than Americans in general to have a parent with a PhD or Masters degree has attracted a lot of attention, and comments suggesting that this is unusual and unsatisfactory. But is it? For various reasons, I’ve interacted quite a bit with farmers, and most of them come from farm families. And historically it was very much the norm for men to follow their fathers’ trade and for women to follow their mothers in working at home.

So, I decided to look for some statistical evidence. I used Kagi’s AI Search, which, unlike lots of AI products is very useful, producing a report with links to (usually reliable) sources. That took me to a report by the Richmond Federal Reserve which had a table from a paper about political dynasties.

I am very pleased that our very own Chris Bertram has responded to Joseph Heath’s very entertaining and polemical “John Rawls and the death of Western Marxism,” a widely shared Substack post [HT: Dailynous]. Chris has made some important corrections to the public record, and the comments on his post are extending that.

As it happens, I just did a three-part series on Heath’s excellent book, The Machinery of Government: Public Administration and the Liberal State (OUP, 2020). [The first one is here; the second here; here.] And I may do a fourth in which I compare his take on cost-benefit analysis with Dave Schmidtz’s. Do read the first few paragraphs of my first post in the series, so you get a sense of my view of the significance of Heath (Toronto), whom I have never met in real life.

Before I get to my criticism of Heath — and I don’t need to remind regular readers I am no Marxist – Heath’s essay is a rare case of auto-biographical history of philosophy in which Heath gets something important right despite the polemical and boundary-policing efforts — note his repeated use of ‘bullshit.’ Usually, such retrospective first-person narratives are only instructive as polemics and boundary-policing (and a window into the anguished grievances of the author).

There has been much attention online to a piece by Joseph Heath arguing that analytical Marxism disappeared because the analytical Marxists all turned into Rawlsian liberals. At a certain level of resolution (blurred, zoomed out) the argument has something going for it. But at that level, all it amounts to is the claim that this group of thinkers shifted their attention over time from critical investigation of the normative and positive claims made by Karl Marx to concerns about justice, and, particularly, distributive justice. Heath’s piece also contains some startling inaccuracies:

- Heath claims that Cohen abandoned the Marxist view, summed up, according to Heath in the belief “that workers are entitled to the fruits of their labour, and so if they receive something less than this, they are being treated unjustly” and Heath associates this view with a commitment to the labour theory of value. But, as any scholar of Marx knows, Marx himself rejected the view that workers are entitled to the full fruits of their labour in the Critique of the Gotha Programme because of the need to make deductions, among others, for those unable to work. Moreover, Cohen rejected the labour theory of value and declared its relationship to the charge of exploitation to be one of irrelevance in his essay “The Labour Theory of Value and the Concept of Exploitation” (available in his History, Labour and Freedom).

-

Heath claims that Cohen, worried about the way that Marx’s theory of exploitation rests on similar premises to Nozick’s views (as he was), spent “spent the better part of a decade agonizing, and wrote two entire books trying to work out a response to Nozick, none of it particularly persuasive.” Well, by my count, Cohen wrote exactly one book responding to Nozick, namely Self-Ownership, Freedom and Equality. Of course it is up to Heath what he finds persuasive, but, personally, I think the great achievement of that book is its focus on the principle of self-ownership and its rejection of that principle.

(Originally drafted for a conference at Frankfurt in 2018 to mark the 40th anniversary of Karl Marx’s Theory of History: A Defence. I’ve done a bit of editing of my conference script and added a few footnotes etc, but it isn’t necessarily produced to the scholarly standards one might require of a journal article.)

In Karl Marx’s Theory of History, G.A. Cohen attributed many of the ills of capitalism to the market mechanism. Later in his career he came to see the market as practically ineliminable. Insofar as he was right about the market in his earlier work, it may turn out that the alternatives to capitalism he championed at the end of his life will also generate the pathology he deplored: the systematic bias in favour of output over leisure and free time. The following explores some of these tensions.

Introduction

In the second half of his career, G.A. Cohen concentrated his discussion of capitalism on its wrongs and injustices. According to his diagnosis, the primary injustice in capitalism arose from the combination of private property and self-ownership, which enables capitalists – who own the means of production – to contract with workers – who own only themselves and their labour power, on terms massively to the capitalists’ advantage. The workers, who produce nearly all of the commodities that possess value in a capitalist society, see the things that they have produced appropriated and turned against them as tools of exploitation and domination by the capitalists. But the wrongness and injustice of capitalism, the theft of what rightfully belongs to workers, is only one part of what is to be deplored about capitalism. In chapter 11 of Karl Marx’s Theory of History, a chapter where he went beyond the expository and reconstructive work he undertook earlier in the book, Cohen articulated a different critique, this time focused not on injustice but on the ills to which capitalism gives rise. In that chapter he attacks capitalism for stunting human potential through a bias towards the maximization of output, a bias which condemns human beings to lives dominated by drudgery and toil. Relatedly, he attacks capitalism both for stimulating demand for consumption that adds little of real value to people’s lives and because for damaging of the natural environment through pollution. In developing this critique, Cohen also notes that the bias towards output he identifies is celebrated by Max Weber as exemplifying rationality itself, a celebration which Cohen thought ideological and mistaken.1

Though both the wrongness and the badness of capitalism arise from the conjunction of private property and the market, it seems natural to emphasize the role of private property more in the production of injustice and to stress market relations more in the genesis of its badness. It is the fact of what the capitalists own that gives them decisive leverage over workers in the labour market, making exploitation within the workplace consequently possible; it is the market that compels everyone, capitalists and workers both on pain of extinction, to act in ways that end up being so destructive for human and planetary well-being.

Harris’ nomination locks in another Boomer presidency. This single generation — those born in the nineteen years between 1946 and 1964 — is guaranteed another presidency. 36 consecutive years, not counting the Biden Interregnum (he’s technically too old).

Despite being a Boomer, you may have noticed that she’s the young, exciting candidate.

According to The New York Times (23 August), The Justice Department “filed an antitrust lawsuit on Friday against the real estate software company RealPage, alleging its software enabled landlords to collude to raise rents across the United States.” I am not an expert in law or anti-trust, but there is another (systemic risk management) angle to this story that the NYT missed, and worth spelling out.

Here’s how the Times summarizes the case:

RealPage’s software, YieldStar, gathers confidential real estate information and is at the heart of the government’s concerns. Landlords, who pay to use the software, share information about rents and occupancy rates that is otherwise confidential. Based on that data, an algorithm generates suggestions for what landlords should charge renters, and those figures are often higher than they would be in a competitive market, according to allegations in the legal complaint. By Danielle Kaye, Lauren Hirsch and David McCabe

There’s more detail in a piece (here) the Times did earlier in the year (July 19, 2024) written by Danielle Kaye. And for a lot more background see this piece in Propublica (here, October 15, 2022). One wonders why the Times waited so long until there was government prosecution to report on this topic.

Before I get to my interest in this story, the coverage highlights two important political angles: (i) this may be a contributing cause to rent inflation because the software allows landlords, which are fairly large companies that use the software, to collude; (ii) there is an interesting issue how this case fits under existing anti-trust law because the collision is kind of indirect mediated, in part, tacitly through a third party. The company itself brags they have “purposely built” their platform “to be legally compliant.” I leave the first issue to economists and the second to lawyers.