by John Holbo on November 28, 2010

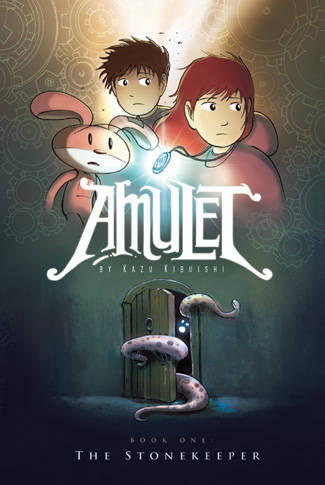

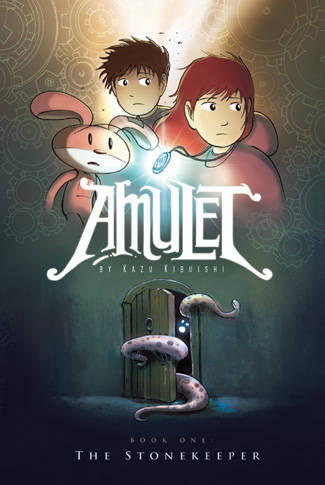

Here’s my pre-X-Mas best books for kids #1 top recommendation: Kazu Kibuishi’s Amulet series. Volumes 1-3 are out so far. So start with The Stonekeeper [amazon]. How they can sell a 200 page full-color graphic novel for under $7 and turn a profit is beyond me.

[amazon]. How they can sell a 200 page full-color graphic novel for under $7 and turn a profit is beyond me.

You can find preview material here. One word about the prologue to volume 1: it’s disturbing because the dad dies. My daughters (ages 6 and 9) almost gave up because that scene upset them so much (note to self: don’t die in car accident). But then it turns into a ripping yarn with a girl hero. Both girls are now of the considered opinion that the Amulet books are ‘the best books ever’.

Check out the rest of Kibuishi’s site – his gallery gives a good sample of his style. I’m thinking about buying my daughters a print for their wall. Maybe ‘the walking house’. Which is the final page from The Stonekeepers. I’ve enjoyed the Kibuishi edited Flight books for several years already. Here’s the preview page for vol. 7. “Premium Cargo” is the best story! Daisy Kutter was good Old West Steampunk fun, but Amulet raises the bar. Not that the story is new. Kid enters strange magical world, turns out to be The Chosen One With A Special Power, has to fight the Dark Power with the help of a small band of fellow fighters and scrappy sidekicks. But it really bounces along in a clever and good-hearted way. Solid dialogue, distinctive characterizations. Nice mix of humor and seriousness and action and sweeping visual spectacle. Stylistically, and world-design-wise, Kibuishi owes a lot to a lot of folks, from Jeff Smith to Hayao Miyazaki. But he’s got his own style, for sure, and it’s a distinct pleasure just to flip through the pages.

by John Holbo on October 18, 2010

by Henry Farrell on October 14, 2010

Felix Gilman’s new book, _The Half-Made World_ is out (Powells, Amazon). I liked it very much indeed (but then, I’ve liked everything that Gilman has written since “stumbling across Thunderer”:https://crookedtimber.org/2009/01/07/thunderer/ ). It’s a steampunk-inflected Western, with a fair dollop of HP Lovecraft thrown in (the malignant ‘Engines,’ whose physical appearance is mostly left undescribed, are genuinely unsettling). The writing is lovely, and the main character a genuinely complex and interesting woman.

[click to continue…]

by John Holbo on October 14, 2010

Must be something in the water. Just as Henry draws our attention to short books, I see AbeBooks is highlighting books with single-letter titles. I could take this as an occasion to mock-deplore the twitterifictation (twitterfaction?) of literature. But life’s too short.

by Henry Farrell on October 12, 2010

“Ars Technica”:http://arstechnica.com/gadgets/news/2010/10/amazon-aims-to-publish-shorter-content-as-kindle-singles.ars

bq. Amazon is rolling out a separate section of its Kindle store meant for shorter content—meatier than long-form journalism, but shorter than a typical book. Called “Kindle Singles,” the content will be distributed like other Kindle books but will likely fall between 10,000 and 30,000 words, or the equivalent of a few chapters from a novel. The company believes that some of the best ideas don’t need to be stretched to more than 50,000 words in order to get in front of readers, nor do they need to be chopped down to the length of a magazine article. “Ideas and the words to deliver them should be crafted to their natural length, not to an artificial marketing length that justifies a particular price or a certain format,” Amazon’s VP of Kindle Content Russ Grandinetti said in a statement. (Anyone who has ever read a terrible “business” or “self-help” book consisting of a single idea furiously puffed up into 200 pages of pabulum will no doubt agree with this sentiment.)

While I’m not greatly enthusiastic about Amazon as a company, I am hopeful that this form of publishing takes off (for reasons I “laid out”:https://crookedtimber.org/2010/02/09/towards-a-world-of-smaller-books/ a couple of years ago). I don’t particularly object to overly long self-help books or business books, since even if they were pithier, they usually would not be worth reading. I presume that the actual functions of these books is (in the case of business books) to provide a common, if conceptually empty, jargon for interacting with work colleagues, and (in the case of self-help books) to provide a symbolic substitute for actual self-help. Shorter electronic versions would not necessarily contribute to either of these functions.

However, I _do_ object to books which have an interesting insight, but pad it out across several chapters to make it publishable. More essays around the 20,000 word mark, taking an interesting point and elaborating it more than would be possible in a standard magazine article, would be a very good thing.

by John Holbo on October 7, 2010

Here’s how you grade a hundred and twenty five papers. Grade five. Take a break. Grade another five. Take a longer break. Repeat.

Really I should be doing yoga or swimming, not looking at any sort of screen at all – but things are a bit slow around here, so …

I like this train. Click link for larger – it’s part of the Field Museum collection.

In other graphical science news, I just finished Atomic Robo Volume 4: Other Strangeness [amazon]. It’s fun! [click to continue…]

[amazon]. It’s fun! [click to continue…]

by John Q on October 1, 2010

I’m paying close attention to Amazon rankings just now[1], and it’s striking that both the #1 and #2 spots in “Economics-Theory” are held by FA Hayek’s Road to Serfdom. Whatever your view of Hayek’s work in general, this is truly bizarre, and indicative of the kind of disconnection from reality going on on the political right. On the natural interpretation, shared by everyone in mainstream economics from Samuelson to Stigler, this book, which argued that the policies advocated by the British Labour Party in 1944 would lead to a totalitarian dictatorship, was a piece of misprediction comparable to Glassman and Hassett’s Dow 36000. So what is going on in the minds of the buyers? Are they crazy? Do they actually think that Hayek was proven right after all? Is there a defensible interpretation of Hayek that makes sense?

[click to continue…]

by Henry Farrell on September 30, 2010

“Tim Lee”:http://www.cato-unbound.org/2010/09/24/tim-lee/of-hayek-and-rubber-tomatoes/ takes exception to my “post of a couple of weeks ago on James Scott and Friedrich von Hayek”:http://www.cato-unbound.org/2010/09/24/tim-lee/of-hayek-and-rubber-tomatoes/, suggesting that I construct a ‘curious straw-man’ of Hayek’s views. Unfortunately, he completely misreads the post in question. Nor – on serious investigation – do his own claims actually stand up.

[click to continue…]

by Harry on September 29, 2010

Over at In Socrates’ Wake (a blog about teaching in philosophy, to which I’ve recently started contributing) we’ve been running a seminar on Martha Nussbaum’s new book Not For Profit: Why Democracy Needs the Humanities (UK

(UK  ). I’ll write a more substantial review here shortly, but it’s well worth reading my ISW colleagues’ takes on it (and the book itself, which I recommend highly — on the back cover no less). Here are the posts so far, in chronological order: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8.

). I’ll write a more substantial review here shortly, but it’s well worth reading my ISW colleagues’ takes on it (and the book itself, which I recommend highly — on the back cover no less). Here are the posts so far, in chronological order: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8.

by Henry Farrell on September 26, 2010

I’m hosting a discussion on China Mieville’s Kraken at FireDogLake, starting 5pm ET. Feel free to drop by if you have any questions for China – I think the URL should be “this”:http://fdlbooksalon.com/2010/09/26/kraken-novel/ and if not, just click on the post at the top of “this page”:http://fdlbooksalon.com/.

by John Q on September 24, 2010

I’ve been living with the text of Zombie Economics for a long time and the cover art came out a while back. But now I finally have my hands on a physical copy of the book, and it’s surprising what a difference the real object makes. My immediate reaction was to open it with dread, sure that some terrible error would jump out at me, but that didn’t happen (no doubt the reviewers will find them, but that’s their job).

With that out of the road, I’ve been filled with irrational confidence. “Surely”, I think, “even the most jaded traveller, passing this book on the airport bookstall, will feel impelled to buy it”. No doubt, this optimistic glow won’t survive the arrival of actual sales figures, but I’m enjoying it while it lasts.

by Henry Farrell on September 15, 2010

Available from “Amazon”:http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/1416588698?ie=UTF8&tag=henryfarrell-20&linkCode=as2&camp=1789&creative=390957&creativeASIN=1416588698 “Powells”:http://www.powells.com/partner/29956/biblio/9781416588696 .

This is a transformative book. It’s the best book on American politics that I’ve read since _Before the Storm._ Not all of it is original (the authors seek to synthesize others’ work as well as present their own, but provide due credit where credit is due). Not all of its arguments are fully supported (the authors provide a strong circumstantial case to support their argument, but don’t have smoking gun evidence on many of the relevant causal relations). But it should transform the ways in which we think about and debate the political economy of the US.

[click to continue…]

by Henry Farrell on September 8, 2010

Scott “reluctantly capitulates”:http://www.insidehighered.com/views/mclemee/mclemee305 to the e-reader revolution.

by Chris Bertram on September 8, 2010

I recently had the pleasure of attending the “European Society for Philosophy and Psychology conference in Bochum, Germany”:http://www.ruhr-uni-bochum.de/philosophy/espp2010/index.html . The highlight for me was attending a talk by “Michael Tomasello”:http://email.eva.mpg.de/~tomas/ of the Max Planck Institute, Leipzig on pre-linguistic communication. Getting home, I ordered a copy of Tomasello’s “Why We Cooperate”:http://www.amazon.com/exec/obidos/ASIN/0262013592/junius-20 in which he argues, on the basis of detailed empirical work with young children and other primates, that humans are hard-wired with certain pro-social dispositions to inform, help, share etc and to engage in norm-guided behaviour of various kinds. Many of the details of Tomasello’s work are controversial (the book is essentially his Tanner Lectures and contains replies by Silk, Dweck, Skyrms and Spelke) and I lack the competence to begin to adjudicate some of the disputes. But this much is, I think, clear: that work in empirical psychology and evolutionary anthropolgy (and related fields) doesn’t – quelle surprise! – support anything like the Hobbesian picture of human nature that lurks at the foundations of microeconomics, rational choice theory and, indeed, in much contemporary and historical political philosophy.

[click to continue…]

by Henry Farrell on September 1, 2010

This “essay”:http://www.thenational.ae/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/20100824/ART/708239962/1200/REVIEW on Eric Rauchway’s _Banana Republican_ by Ben East is rather dim-witted. Not because it displays no evidence whatsoever of actually having read the book under discussion (instead being a review essay based on a couple of sentences in someone other’s review), although it does not. Nor because it makes a sweeping judgment that “critics” (the plural is a stretch, since the only critic mentioned is Joe Queenan of the New York Times) have dismissed the book as not well written (as it happens, Queenan’s “issue”:http://www.nytimes.com/2010/08/08/books/review/Queenan-t.html is that the writing is _too_ good to plausibly reflect the thought processes of Tom Buchanan). Nor yet because elevates a purely personal crochet into a universal aesthetic principle, although it does that too. It’s because it completely misses the point.

bq. Without believable characters, novels are nothing. So it isn’t particularly surprising that sometimes, authors take the somewhat safer option. They “borrow” characters from other writers’ works – the more famous, the better – and place them in their own books. … So why do authors continue to use well-known characters? Is it a self-imposed challenge to carry on somebody else’s iconic work, or just an easy way to make a quick buck? … Banana Republican, gives Tom Buchanan – the racist, snobbish, despicable excuse for a human being in F Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby – a second chance. … The New York Times called it a gimmick: “It’s as if Rauchway wrote a generic farce about a long-forgotten revolution and then decided the book might get more attention if he recast the narrator as a refugee from The Great Gatsby,” wrote Joe Queenan. … Perhaps, I suggest, the difficulty is that readers often feel authors are writing with somebody else’s characters because they know they have a ready-made audience. That, well, they’re being just a little lazy and unimaginative. … “

There’s a very obvious reason why Rauchway has “borrowed” the character of Tom Buchanan. He’s riffing on a famous “borrowing” that sought to do for nineteenth century British imperialism what Rauchway wants to do for the early twentieth century version – the exploits of “Sir Harry Paget Flashman, VC”:http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harry_Paget_Flashman. Flashman was, of course, the bully who gets sent down from Rugby in Thomas Hughes’ _Tom Brown’s Schooldays._ McDonald Fraser appropriates this character from a novel that is in every way inferior to his own books, problematic though they are in some ways, and transforms him from a thick-headed boor into an intelligent, charming, selfish and completely cowardly representative of the British upper classes. Queenan notes the broad resemblance between _Banana Republican_ and the Flashman novels, but seems completely ignorant of the fact that Flashman is himself a borrowing from another novel, suggesting that he needs to pay a little more attention to the stuff that he’s reading. That East elevates this misreading into a fundamental principle of aesthetics (that those who use other’s characters in their own novels are lazy, unimaginative, and timorous and that their novels, with a tiny list of exceptions are failures), suggests that his problem is rather more fundamental. Indeed, if one wanted to apply adjectives to a critic who doesn’t seem to have actually _read_ the book he’s trying to take down (East makes _no_ independent judgments of the book in the course of the review-essay), lazy, unimaginative and timorous might be excellent ones to start out with. Matt Yglesias wrote somewhere that _the National_ pays remarkably well for book reviews. If I were them, I’d be asking for their money back.

[updated to clarify argument]

[amazon]. How they can sell a 200 page full-color graphic novel for under $7 and turn a profit is beyond me.