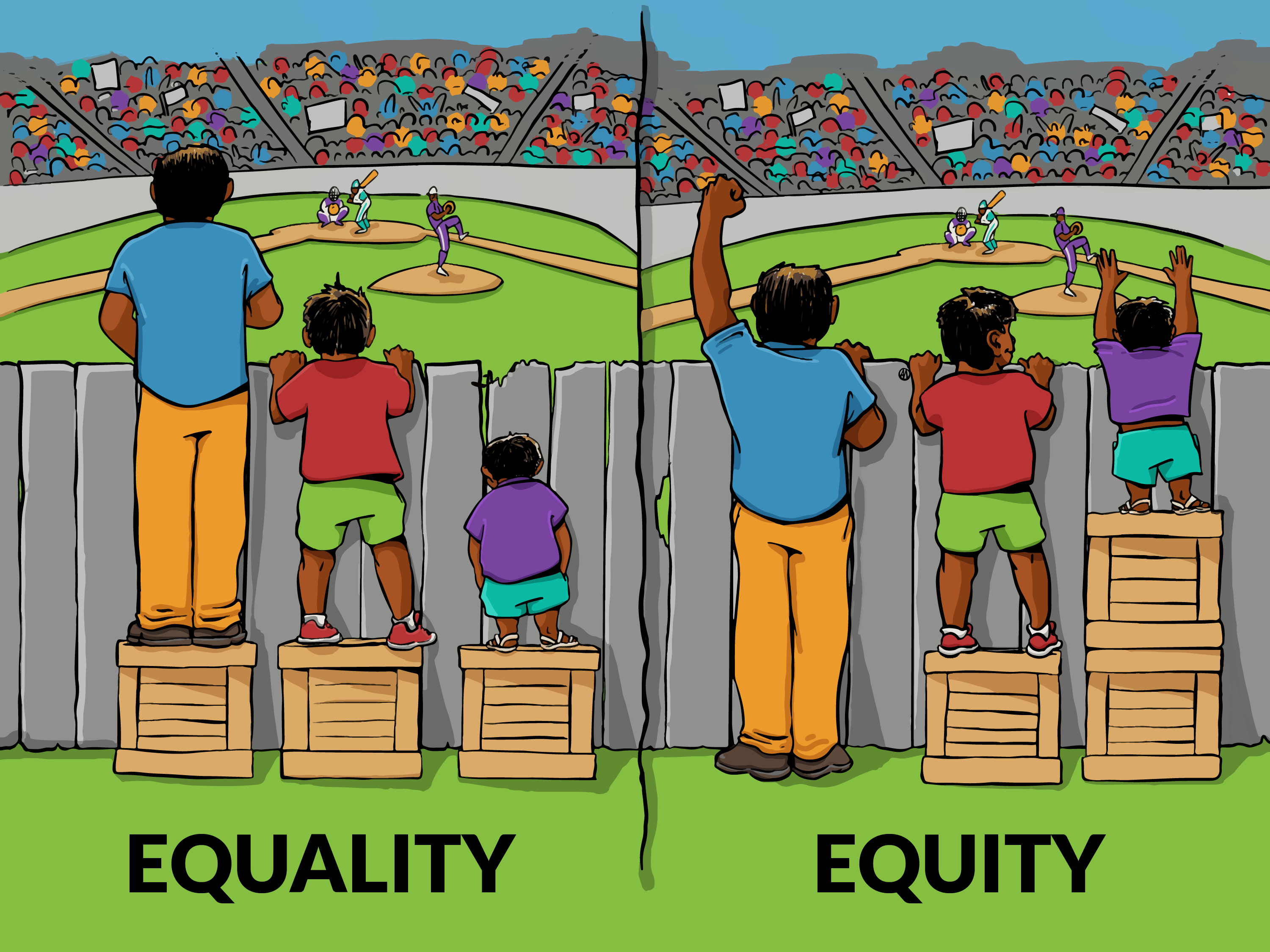

Hélène Landemore enthusiastically shared a piece, “The Inflation of Concepts,” published at Aeon by John Tasioulas (who she describes as her “Oxford colleague”). Appealing to the work of Jürgen Habermas and John Rawls, Tasioulas focuses on a “threat to the quality of public reason” (which he claims) “tends to go unnoticed. This is the degradation of the core ideas mobilised in exercises of public reason.” And, in particular, what he has in mind is ‘conceptual overreach’. This “occurs when a particular concept undergoes a process of expansion or inflation in which it absorbs ideas and demands that are foreign to it.”

At this point I kind of expected Tasioulas to suggest as an example ‘democracy’ but he initially focuses on “human rights or the rule of law” [he is a legal philosopher] which “is taken to offer a comprehensive political ideology, as opposed to picking out one among many elements upon which our political thinking needs to draw and hold in balance when arriving at justified responses to the problems of our time.” Near the end of his essay he does focus on democracy (which he thinks of as a more “contestable” example!) and while drawing on the excellent work of Joshua Ober, he complains that some people mistakenly use ‘democracy’ and ‘liberal democracy’ interchangeably. (Our reading habits are clearly different because most of the conflations I see involve ‘democracy’ and whatever views a theorist expects/wishes to see approved by their imaginary demos.)