From the category archives:

Academia

In the meantime, for a good example of what *not* to say about Gaza, you could try this piece. (In a nutshell, Yuval Noah Harari’s solution seems to be that Israel hands the problem over to a coalition of the willing who will administer Gaza colonial-style. I can envisage a few problems).

Given the latest catastrophe in Israel/Palestine, it’s time for me to repost my comprehensive plan for US policy in the Middle East, just as applicable now as it was when I suggested it back in 2011.

As usual, it’s over the fold.

If you haven’t yet listened to Emily Hanford’s Sold a Story, you probably should, now. It’s brilliant, if profoundly depressing. Very brief synopsis: the methods routinely used to teach children to read in the US don’t work well for large numbers of children, and the science of reading has been clear about this for decades. Three academics in particular — Lucy Calkins of Teachers College, and Irene Fountas and Gay Su Pinnell of the Ohio State University — are responsible for promoting these bad practices (which are pervasive), and persisted in doing so long after the research was clear, and have gotten very rich (by the standards of academics) from the curriculum sales/speaking circuit.[1] Hanford’s documentary has single-handedly changed the environment, and in the past couple of years State departments of education and even school districts throughout the country have been scrabbling to reform, often under the eye of state legislators who have been alerted to the situation by the amount of chatter that Sold a Story has generated.

Although a great admirer of Hanford’s work, which I have known and followed for many years, it took me a while to listen to Sold a Story. By the time I did I was familiar with the basic narrative which, I think, freed my mind to wonder about something that Hanford doesn’t discuss. The role of academic bystanders. People like me.

[click to continue…]

A few weeks ago, Cyril Hédoin responded insightfully and constructively (here) to an essay I recently published @Liberal Currents. Subsequently, he did a follow up piece in which he assimilated my stance on what I call the ‘platonic skepticism’ (more on that below) of liberalism into a larger framework about different kinds of skepticism exhibited by liberals.

In the piece that triggered Hédoin’s response, I argued that so-called public reason liberalism (made influential by Rawls) and French Laïcité, or radical secularism, share three features: (i) they transcend the right/left opposition, (ii) they demand considerable public censorship, and (iii) they are both grounded in a Platonic skepticism about the ability of truth to dominate mere opinion in a democratic context.* My own alternative (liberal) position, accepts a version of (iii), but rejects (i-ii) as inimical to healthy liberal political life. So far so good.

SIGMA Moves

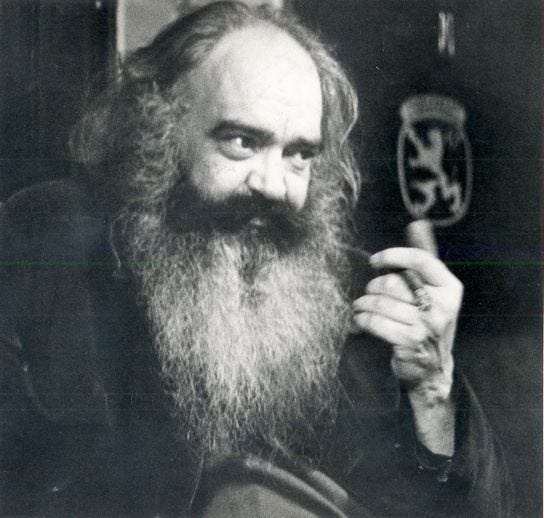

During the pandemic, I was seduced by a charming British management consultant. A debonair James Bond-type who went from driving a Rolls Royce around his countryside estate to orchestrating the Chilean economic experiment under Allende to teaching Brian Eno about the principles of complex systems in a stone cottage in Wales. Stafford Beer lived a remarkable life,

What the abandonment of the pinnacle of capitalist achievement for the most realistic effort to build cybernetic socialism does to a mfer.

It’s time for me to have my final say on a dispute with Matt Yglesias that has been going at a fairly slow pace.

A couple of weeks ago, Matt put up a post (really a Substack newsletter, but I still think in blog terms), headlined Polarization is a choice with the subtitle, “Political elites justify polarizing decisions with self-fulfilling prophesies”

I responded with a snarky but (I thought) self-explanatory note, saying “Peak both sidesism here. Republicans want to overthrow US democracy, while Democrats stubbornly insist on keeping it. Surely there is some middle ground to be found here

A few days ago, Matt came back to ask “I’m curious what actual things the article says you believe are wrong. You clearly didn’t like it since you choose to mischaracterize it in a mean-spirited way, but I’m not sure what you didn’t like about it.”

So, here’s my response.

[click to continue…]

Sorry, when you are semi-retired and in France anyway, easy to forget days of the week. Here’s an iPhone photo, from when I happened to be out and about in Pézenas. The wall is actually something to do with a local sport, possibly “jeu de tambourin”, but I’m not quite sure of its function, and the former playing area is now a car park.

Tomorrow morning brings the 50th anniversary of the coup in Chile and the death of Salvador Allende [Le Monde has that photo], a coup which was, of course, followed by mass incarcerations, witch-hunts and murders and by the exile as political refugees of many Chileans of the left. (In today’s climate those exiles would have struggled to find sanctuary. Perhaps Sunak and Braverman would have put them on the Bibby Stockholm, a marginal improvement on a Santiago football statium.) I remember the coup, sort of, as a teenager. But not clearly: it was something shocking and far away. But the years of aftermath I do remember: meeting exiles, Latin American solidarity campaigns with them, the showings of films like The Battle of Chile and, later, Missing.

I have nothing particularly insightful to say now about the coup itself, or the later, shameful failure of the British to hold Pinochet to account for his crimes (“he was only giving orders”). But, in an atmosphere where the political right from Fox News to the British Daily Telegraph to France’s C-News whip up paranoid fantasies that might serve to legitimate “pre-emptive” action even against liberal democracies, and where Donald Trump remains a threat, it is worth re-reading Ralph Miliband’s essay from 1973, and particularly his thoughts about the editor of the London Times:

In so far as Chile was a bourgeois democracy, what happened there is about bourgeois democracy, and about what may also happen in other bourgeois democracies. After all, The Times, on the morrow of the coup, was writing (and the words ought to be carefully memorized by people on the Left): “… whether or not the armed forces were right to do what they have done, the circumstances were such that a reasonable military man could in good faith have thought it his constitutional duty to intervene”. Should a similar episode occur in Britain, it is a fair bet that, whoever else is inside Wembley Stadium, it won’t be the Editor of The Times: he will be busy writing editorials regretting this and that, but agreeing, however reluctantly, that, taking all circumstances into account, and notwithstanding the agonizing character of the choice, there was no alternative but for reasonable military men … and so on and so forth.

Our cultural excitement for the week was a visit to the spectacular Château Laurens in Agde, an art nouveau villa built at the end of the 19th century by a spectacularly rich idle opium smoker and yachtsman, sold to friends when he lost all his money, locked up for 50 years and then reopened in June. It is right next to the railway (modernity!) and was built there so the trains could stop outside, and his friends could alight and drink champagne in the garden. Lots of other pics on my Flickr, but one below.

Michela Murgia – a very fine writer, and probably the most widely known feminist public intellectual within the Italian cultural landscape of the last couple of decades – died at the beginning of last month. She wasn’t very well known abroad, not even simply as a writer (her most widely acclaimed and awarded novel, Accabadora, was translated into English, and got some appreciative reviews, but that was it). I think she deserved to be, but that’s another story, and it’s now a bit too late for a celebratory obituary anyway. What I would instead like to share with you are two thoughts about how much potential the role she decided to incarnate as a public intellectual had…and yet how little it seemed to make a dent beyond the usual suspects. [click to continue…]

(This is another post in my series on Michigan politics, broadly construed.)

Why am I thinking about 1961? Because that was one year before University of Michigan students published the Port Huron Statement, a pivotal document that laid out the intellectual foundations of New Left student activism. (Excellent UM exhibit on the statement here.) I am wondering whether UM students today, and U.S. university students more generally, are on the cusp of a generation-shaping leftist activist mobilization that will fundamentally transform U.S. politics, as UM students and university students more broadly were in 1961.