That’s the headline[1] for my latest piece in the Canberra Times. It doesn’t appear to be paywalled, but I’m including the text over the fold.

[click to continue…]From the category archives:

Books

I’m going to end this little series of positive notes I started ten days ago with sharing several excellent nonfiction books I read in 2020. Last year, my goal was to read 52 books. A year ago I had set as my goal for 2020 60 books, not because I knew we’d all be experiencing a lockdown, but because I was supposed to be on sabbatical in the fall and figured I’d be able to make more time for it. (I was indeed on sabbatical this past fall, but I did not “go” on sabbatical in that I just stayed in Zurich rather than my original plan of spending it at my alma mater Smith College in a special visiting position. Fortunately, we were able to reschedule that for fall ’23.) It turns out, during lockdown March-May I didn’t read any books at all. I can’t explain it, but it’s not how I coped. Fortunately, during the rest of the year I caught up. I already posted separately my resulting fiction recommendations, now for the rest.

I started 2020 with a tough, but very important and well-written book: Know My Name by Chanel Miller. This is the story of the woman who had been sexually assaulted by Brock Turner on Stanford’s campus. She goes through so much of what happened in the aftermath including lots of discussion of the crazy legal system that lets people like Turner move on with their lives while the lives they assault are forever changed. I believe this should be required reading on university campuses. It would be very hard for 18-year-olds to process (it’s hard to process at any age), but valuable.

While we are on the topic of sexual assault, [click to continue…]

I decided to dedicate two separate posts to books, this one is for fiction. I usually don’t read much fiction so last year I wouldn’t have had enough to write about for such a post (and what I did read I didn’t like so wouldn’t have wanted to write about it). I still don’t have that much, the hope is that you’ll add your own. Like last year, this is not about books that were published in 2020, I am just sharing what I read in 2020 and recommend.

My big reading innovation this year, by the way, was listening to audiobooks. It helped me read more since I can still follow along comfortably at 1.5x speed, often even 1.75x or 2x speed, which is definitely faster than I read. Importantly, it lets me multitask so I can make progress on a book while cooking or working on a jigsaw puzzle (one of my pandemic sanity preoccupations although some of you may recall that this wasn’t a pandemic novelty for me).

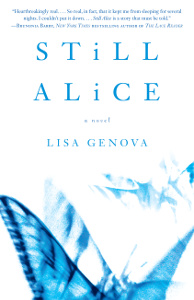

This book is definitely not new, it’s even been made into a movie already (I haven’t seen it), but I only came across it this year: Still Alice by Lisa Genova (2007). It’s a tough topic, early onset Alzheimer’s in an academic. It’s beautifully written and the best fictional depiction of academia I have seen (but again, to be fair, I don’t see that much fiction). It did make me rather paranoid, but following up on the book I also read about things one can do to help delay onset (FWIW, solving crossword puzzles is not one of them).

Another extract from my book-in-progress, Economic Consequences of the Pandemic

Over the course of the Covid-19 pandemic, governments around the world have issued huge amounts of public debt, much of which has been purchased by central banks. In the US, for example, Federal public debt increased by $3 trillion over the course of 2020 (this is about 15 per cent of US national income)

while the monetary base (money created directly by the Federal Reserve) increased by around $1.6 trillion. This money was used to buy government bonds along with corporate securities in open market operations (what is now called Quantitative Easing)

These policies represent a complete repudiation of assumptions which were considered unquestionable by the political class until relatively recently: that budgets should be balanced, and that public debt is always undesirable.

Even the most widely-accepted modifications of these assumptions are now problematic. A standard view is that budget balances should be stable over the course of the economic cycle. If measured appropriately, this entails a stable ratio of public debt to national income.

But where should this ratio be set?

[click to continue…][Warning: half-formed thoughts ahead]

One of the most striking characteristics of the 21st century economy (divided into goods, human contact services and information) is that even very poor people have access to information-based services that were almost unimaginable 30 years ago. Given free wifi and a second-hand phone, someone lining up at a food bank can blog about the experience, and possibly attract readers all around the world[1]. Or they can entertain themselves with an endless supply of free books, news media, music and videos. That’s great, but it doesn’t change the fact that people in both rich and poor countries are going hungry.

Economics has traditionally been about scarcity. But now we have one part of the economy where scarcity remains dominant, and another, growing part, where it has just about disappeared. That raises a lot of different issues.

First, while we are accustomed to think of things like economic growth and inflation rates as objective facts, they are actually based on index numbers, which are the products of theoretical models. Those models don’t work well when an increasing part of the economy consists of information services that are becoming radically cheaper all the time. As a result, much of the debate about the desirability or otherwise of growth is misconceived.

A positive implication is that we can anticipate improving standards of living, because of ever-increasing access to information services, without economic growth in the 20th century sense of steadily increasing throughput of materials and energy, and correspondingly increasing environmental damage. T

A negative implication is that real incomes (that is, incomes deflated by a consumer price index) can increase, even as basic needs like food and housing become less affordable, because the price of inforamation related services is falling fast. I can’t find much that’s readily accessible on this – pointers would be appreciated. One notable fact is that the proportion of disposable income spent on food, which fell sharply between 1960 and 1998, has remained almost static since then. The price of food seems to have risen a little faster than the CPI over this period.

I haven’t talked yet about human contact services. Scarcity is just as relevant here as in the goods economy. Governments are heavily involved in funding and providing these services, and the quality of services is hard to measure. As a result, the kinds of services people get aren’t determined simply by their capacity to pay.

A question to which I don’t have an answer. Is there some way to exploit the massively increased productivity of information services to allow more, and more equal, provision of basic goods? This question underlies a lot of discussion about Universal Basic Income and similar ideas, but is rarely posed in a satisfactory way, let alone answered.

As you can tell, I’m struggling with some complicated problems here, so any thoughts welcome.

fn1. In the early days of blogging, thehomelessguy [Kevin Barbieux] did exactly this. His most recent site is here.

Last year, getting started on my book I posted some facts and claims about the 21st economy. The key points (slightly elaborated)

(1) Most economic activity in the 20th century, including ‘primary’ industries like agriculture and mining and services such as wholesale and retail trade, was fairly directly related to the production and distribution of manufactured goods

(2) This is no longer true: around half of all employment is now related to human services, information services and finance, and these are at most indirectly related to goods production.

On the basis of (1), the 20th century economy could properly be described as ‘industrial’. The economy of the early 21st century is harder to classify. Information technology and communications play a central role in the economy and society, and are the main focus of technological progress, but don’t employ all that many people. Service industries employ most people, but it’s critical to distinguish between services that are part of the industrial goods economy and human services like health and education. So, neither ‘service economy’ nor ‘information economy’ captures the whole picture. ‘Post-industrial’ carries too many implicit assumptions, as does the use of the ‘post’ prefix in general.

But that’s just semantics. The key point for the book is how the pandemic changed the different parts of the economy, and to what extent those changes will be sustained. A general observation is that the changes most likely to be permanent are those that reinforce processes that were already underway. So, some thoughts

As was the case with Economics in Two Lessons, I’ve been struggling with the material for my book-in-progress, The Economic Consequences of the Pandemic. But I’ve now managed to put together a synopsis I can work with. I’d very much appreciate comments, including but not limited to: topics I should be covering; issues raised by the brief summaries; and useful references. Thanks for comments so far, and thanks in advance for more.

The last (I hope) extract from the climate change chapter of Economic Consequences of the Pandemic. I’m in two minds about whether this is really needed. The group of pro-nuclear environmentalists seems to be shrinking towards a hard core who can’t be convinced (and some of them, like Shellenberger turn out to have been concern trolls all along). But every now and then I run across people who seem open-minded enough, but haven’t caught up with the bad news on nuclear.

Another excerpt from the climate chapter of my book-in-progress, Economic Consequences of the Pandemic. Comments, constructive criticism and compliments all appreciated.

Over the fold, another draft section of the climate chapter of Economic Consequences of the Pandemic. As always, comments, compliments and criticism appreciated

Another extract from the climate chapter of my book-in-progress, Economic Consequences of the Pandemic, over the fold

[click to continue…]Another (long) extract from the climate chapter of my book-in-progress Economic Consequences of the Pandemic is over the fold. Comments, compliments and criticism appreciated as ever.

[click to continue…]

(Another extract from the climate chapter of my book-in-progress, Economic Consequences of the Pandemic)

The Covid-19 pandemic has accelerated a variety of social and economic trends, some beneficial and some harmful, that were already underway before 2020.

An important example of a beneficial effect has been an acceleration of the decline of carbon-based fuels. Lockdowns early in the pandemic produced a substantial reduction in demand for both electricity and transport. As well as providing a brief glimpse of a world with greatly reduced atmospheric pollution, the lockdown accelerated shifts in the energy mix that were already underway.

Since solar PV and wind plants cost nothing to operate, the reduction in electricity demand fell most severely on carbon-based fuels, particularly coal. As a result, the combined contribution of PV, wind and hydroelectricity to US energy generation surpassed that of coal for the first time in 130 years.

Official projections from the EIA suggest that coal use will return to its gradually declining trend in the wake of the pandemic, exceeding renewables for some years to come. However, the pace at which coal plants are being closed or converted to run on gas has accelerated during pandemic. Meanwhile, despite weak demand, wind and PV plants are being installed at a record pace, partly because near-zero interest rates make capital investments cheaper.

The reduction in transport usage reduced demand for oil, at one point leading to a startling situation where the price of oil was negative, as unsold oil exceed the capacity for storage. Although the price has recovered somewhat, it seems unlikely that transport demand will return to its previous trend.

At the same time, there has been continued progress, both technological and political, in the electrification of transport. British Prime Minister Boris Johnson recently announced that the sale of petrol and diesel cars would be prohibited after 2030, an advance on previous commitments. The decline in long-term interest rates also enhances the economic position of electric vehicles, which have higher upfront costs and lower operating and maintenance costs than petrol and diesel vehicles. https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/auto-loan-interest-rates-drop-in-may-to-lowest-level-since-2013-according-to-edmunds-301069143.html

Not all energy-related developments associated with Covid have been positive. The convenience and cheapness of online taxi platforms like Uber and Lyft has reduced use of public transport in many cities. The pandemic, with the need to avoid crowded spaces like buses and subway cars has exacerbated this trend. And, while the option of working remotely reduces the need for travel, it has encouraged a more dispersed workforce with less need to commute to the central city locations best served by public transport.

Even as the future of US democracy remains in the balance, and as the pandemic still rages, I’m still working on my book The Economic Consequences of the Pandemic. At this stage, it’s hard to get a clear idea of how things will look when and if the pandemic is brought under control. One thing that is certain is that the problem of climate change/global heating will not have gone away. Over the fold, the intro for the chapter I’m writing on this topic. Comments, criticism and compliments all gratefully accepted.

This week is the 2020 Open Access week. I’m using the occasion to share my experiences with publishing a book open access, now almost 3 years ago. I’ve had multiple emails since publishing that book, mainly from established scholars who had earlier published with world-leading academic publishers, and who were wondering whether or not they should opt for a genuine non-profit open access publisher for their next book project. [click to continue…]